View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Painted Milkvetch - Astragalus ceramicus var. filifolius

Other Names:

Pottery Milkvetch

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Astragalus ceramicus variety filifolius is associated with sandy soils of the sandhills and sandstone outcrops in eastern Montana. It is known from about 20 occurrences observed mostly from 1983 to 2000. Some populations occur in State Parks. The Flora of the Great Plains (1986) considered it rare for the region except in the Nebraska sandhill area where it was somewhat common. Based on aging data, limited distribution, and an association to specific habitat types it is considered a Species of Concern. Current data on locations, populations sizes, and threats is greatly needed.

- Details on Status Ranking and Review

Range Extent

ScoreF - 20,000-200,000 sq km (~8,000-80,000 sq mi)

Area of Occupancy

ScoreD - 6-25 4-km2 grid cells

Number of Populations

ScoreB - 6 - 20

Number of Occurrences or Percent Area with Good Viability / Ecological Integrity

ScoreC - Few (4-12) occurrences with excellent or good viability or ecological integrity

Threats

ScoreCD - Medium - Low

CommentThreat Categories include: Habitat shifting & alteration (real), Recreational activities (potential), and Invasive non-native/alien species/diseases (potential). Plants require early successional habitat maintained by grazing or fire; therefore, sand dune

General Description

PLANTS: Perennial from rhizome-like caudex-branches (Barneby 1964). The root-crown is deeply buried but can become exposed by shifting sand of mobile dunes (Barneby 1964). Plants are densely strigose (Lesica et al. 2012). Stems solitary, lax to ascending, 10–25 cm (Lesica et al. 2012).

LEAVES: 1–12 cm long. Mostly pinnate with 1-7 leaflets; the terminal leaflet is longest and confluent with the rachis (Lesica et al. 2012). Petioles are slender (Barneby 1964). Stipules are lanceolate, 2–6 mm long, and often united basally.

INFLORESCENCE: Racemes of 2-10(25) white to light purple flowers. Racemes with spreading to ascending flowers grow among the leaves (Lesica et al. 2012).

In Montana two varieties are present, filifolius and apus. Refer below to Diagnostic Characteristics and Range Comments.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Astragalus ceramicus is unique in being diffusely cryptophytic (bears its buds below the soil), with confluent terminal leaflets, and an inflated pod that does not lose its red mottling (Barneby 1964). Its pods (fruits) are balloon-shaped, large, and red-mottled.

Variety

filifolius has pods that have a stipe of 1-3 mm length and grows in the counties of eastern Montana, adjacent North and South Dakota, and other regions of the Great Plains (McGregor 1986, Flora of the Great Plains). Pods are (2)3-5 cm long and 1.4-2.6 cm in diameter (Barneby 1964). Some lower leaves may have 1-2(3) pairs of lateral leaflets (Barneby 1964).

Variety

apus has pods that are sessile to the stem and is endemic to Beaverhead County and adjacent Idaho (Lesica et al. 2012). Pods are 2-4 cm long and about 1.5-2.4 cm in diameter (Barneby 1964). Lateral leaflets are wanting or nearly so (Barneby 1964).

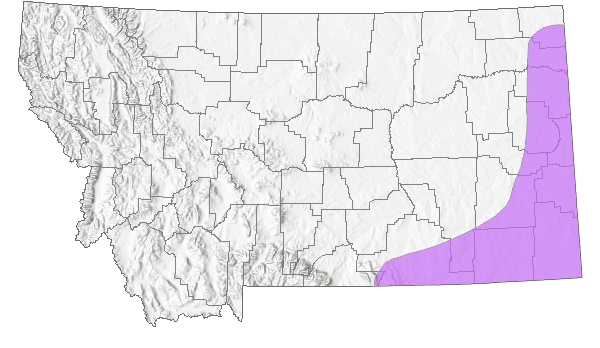

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

Variety apus is endemic to Beaverhead County and adjacent Idaho (Lesica et al. 2012).

Variety filifolius grows in the counties of eastern Montana, adjacent North and South Dakota, and other regions of the Great Plains (Barneby 1964). It is rare in the Great Plains except in the sandhill region of Nebraska where it is common (McGregor 1986, Flora of the Great Plains).

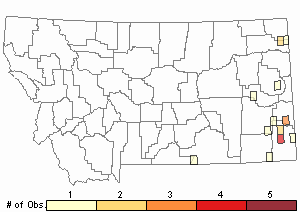

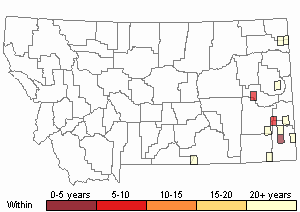

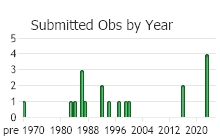

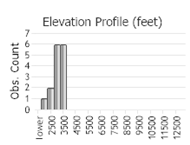

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 31

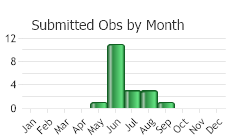

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Sand or very sandy soil of sandhills, below sandstone outcrops; plains, valleys, montane (Lesica et al. 2012).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Grassland

Lowland - Prairie Grassland

Ecology

Long distances between occurrences is thought to reduce opportunities for pollen exchange and has led to the perpetuation of small regional differences that consist of many minor races (Barneby 1964). Three varieties have been recognized since at least 1964:

ceramicus, apus, and filifolius of which the latter two occur in Montana and are depicted in their own Plant Field Guide accounts.

POLLINATORS The following animal species have been reported as pollinators of this plant species or its genus where their geographic ranges overlap:

Bombus vagans,

Bombus appositus,

Bombus auricomus,

Bombus bifarius,

Bombus borealis,

Bombus centralis,

Bombus fervidus,

Bombus flavifrons,

Bombus huntii,

Bombus mixtus,

Bombus nevadensis,

Bombus rufocinctus,

Bombus ternarius,

Bombus terricola,

Bombus occidentalis,

Bombus pensylvanicus,

Bombus griseocollis, and

Bombus insularis (Macior 1974, Thorp et al. 1983, Mayer et al. 2000, Colla and Dumesh 2010, Wilson et al. 2010, Koch et al. 2012, Miller-Struttmann and Galen 2014, Williams et al. 2014).

Reproductive Characteristics

Flowers white to light purple; calyx white- and/or black-strigose; sepals 2–3 mm long; banner reflexed, 8–11 mm long; keel 6–8 mm long. Legume ovoid, inflated, 15–40 mm long, maroon-mottled, glabrous, papery, pendent (Lesica et al. 2012).

Management

The removal of natural disturbance regimes, including fire, ungulate grazing and pocket gopher activity, leads to dune stabilization and reduces the extent of early seral blowout vegetation areas upon which this species depends. Painted milkvetch would benefit from restoration of the fire regime and moderate grazing, at least in years following burns. Severe destabilization of the dunes, e.g., from off-road vehicle use, could also threaten its habitat.

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Studies have shown that Pottery Milkvetch occurs in early successional habitats that are maintained by grazing or fire. Threats would include any process or action that hinders or prevents grazing or fire; however, the scope, severity, or timing of such threats have not been documented (MTNHP Threat Assessment 2021).

Plants occur in habitats where the potential for off-highway vehicle use is real; however, actual use has not been documented at any known occurrence.

Invasive plants are a potential threat to its habitat though current assessments on the condition of occupied habitats have not been made.

STATE THREAT SCORE REASON

A reported threat to Montana’s populations of Painted Milkvetch includes natural ecological succession of the habitat (MTNHP Threat Assessment 2021). Plants require early successional habitat, which can be maintained by grazing and/or fire. Potential threats to populations could also come from incompatible recreational activities and invasion by non-native plant species is greatly needed (MTNHP Threat Assessment 2021).

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Barneby, R.C. 1964. Atlas of North American Astragalus. 2 Vols. New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York. 1188 pp.

Barneby, R.C. 1964. Atlas of North American Astragalus. 2 Vols. New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York. 1188 pp. Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68.

Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68. Koch, J., J. Strange, and P. Williams. 2012. Bumble bees of the western United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 143 p.

Koch, J., J. Strange, and P. Williams. 2012. Bumble bees of the western United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 143 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Macior, L.M. 1974. Pollination ecology of the Front Range of the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Melanderia 15: 1-59.

Macior, L.M. 1974. Pollination ecology of the Front Range of the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Melanderia 15: 1-59. Martin, B., S. Cooper, B. Heidel, T. Hildebrand, G. Jones, D. Lenz, and P. Lesica. 1998. Natural community inventory within landscapes in the Northern Great Plains Steppe Ecoregion of the United States. Unpublished report to the Natural Resource Conservation Service, Northern Plains Regional Office. The Nature Conservancy, Montana Field Office, Helena. 211pp.

Martin, B., S. Cooper, B. Heidel, T. Hildebrand, G. Jones, D. Lenz, and P. Lesica. 1998. Natural community inventory within landscapes in the Northern Great Plains Steppe Ecoregion of the United States. Unpublished report to the Natural Resource Conservation Service, Northern Plains Regional Office. The Nature Conservancy, Montana Field Office, Helena. 211pp. Mayer, D.F., E.R. Miliczky, B.F. Finnigan, and C.A. Johnson. 2000. The bee fauna (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of southeastern Washington. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 97: 25-31.

Mayer, D.F., E.R. Miliczky, B.F. Finnigan, and C.A. Johnson. 2000. The bee fauna (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of southeastern Washington. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 97: 25-31. McGregor, R.L. (coordinator), T.M. Barkley, R.E. Brooks, and E.K. Schofield (eds). 1986. Flora of the Great Plains: Great Plains Flora Association. Lawrence, KS: Univ. Press Kansas. 1392 pp.

McGregor, R.L. (coordinator), T.M. Barkley, R.E. Brooks, and E.K. Schofield (eds). 1986. Flora of the Great Plains: Great Plains Flora Association. Lawrence, KS: Univ. Press Kansas. 1392 pp. Miller-Struttmann, N.E. and C. Galen. 2014. High-altitude multi-taskers: bumble bee food plant use broadens along an altitudinal productivity gradient. Oecologia 176:1033-1045.

Miller-Struttmann, N.E. and C. Galen. 2014. High-altitude multi-taskers: bumble bee food plant use broadens along an altitudinal productivity gradient. Oecologia 176:1033-1045. MTNHP Threat Assessment. 2021. State Threat Score Assignment and Assessment of Reported Threats from 2006 to 2021 for State-listed Vascular Plants. Botany Program, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana.

MTNHP Threat Assessment. 2021. State Threat Score Assignment and Assessment of Reported Threats from 2006 to 2021 for State-listed Vascular Plants. Botany Program, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79.

Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79. Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p.

Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p. Wilson, J.S., L.E. Wilson, L.D. Loftis, and T. Griswold. 2010. The montane bee fauna of north central Washington, USA, with floral associations. Western North American Naturalist 70(2): 198-207.

Wilson, J.S., L.E. Wilson, L.D. Loftis, and T. Griswold. 2010. The montane bee fauna of north central Washington, USA, with floral associations. Western North American Naturalist 70(2): 198-207.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Painted Milkvetch"