View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

- Home - Other Field Guides

- Kingdom - - Animalia

- Phylum - Spiders, Insects, and Crustaceans - Arthropoda

- Class - Insects - Insecta

- Order - Sawflies / Wasps / Bees / Ants - Hymenoptera

- Family - Bumble, Honey, Carpenter, Stingless, & Orchid Bees - Apidae

- Species - Yellow Head Bumble Bee - Bombus flavifrons

Yellow Head Bumble Bee - Bombus flavifrons

Other Names:

Yellow-fronted Bumble Bee,

Pyrobombus flavifrons

Native Species

Global Rank:

G5

State Rank:

S5

(see State Rank Reason below)

Agency Status

USFWS:

USFS:

BLM:

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is widely distributed across western and central Montana and relatively common within suitable habitat. Trend appears stable and does not appear to face significant threats.

General Description

For definitions and diagrams of bumble bee morphology please see the

Montana State Entomology Collection's Bumble Bee Morphology page. A long-tongued, small-sized bumble bee: queens 16-18 m in length, workers 10-13 mm. Hair length medium to long and uneven. Head long, cheek distinctly longer than wide; mid-leg basitarsus with back far corner rounded, outer surface of hind-leg tibia smooth and hairless (except fringe) forming pollen basket; hair of face and upper side of head pale yellow with many black hairs intermixed giving cloudy appearance; upper side of thorax in front of wing bases with pale yellow hairs usually intermixed with black giving a cloudy appearance, at the back of thorax the pale yellow usually distinct with with predominantly pale hair; T1-2 yellow and often interrupted in middle with black hair especially broad at front (or sometimes without black), T3-4 red or black with yellow at sides, S3-5 predominantly yellow, T5 black sometimes with fringe at back yellow or rarely extensively brownish-yellow. Males 10-14 mm in length; eyes similar in size and shape to eyes of any female bumble bee; antennae medium length, flagellum 2.5-3X length of scape; hair color pattern similar to queens and workers, but upper side of thorax yellow at front (scutum) often with few or no black hairs intermixed at mid-line, sometime with more black often making black band between wings indistinct; yellow band on upper side of thorax at back often with many scattered black hairs intermixed especially near midline; T1-2 yellow, T3-4 almost always with at least a few black hairs intermixed near midline, if T3-4 red then T5 sometimes also red, if T3-4 lack red, then often extensively yellow (Koch et al. 2012, Williams et al. 2014).

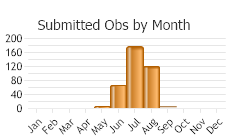

Phenology

Across the range, queens reported March to September, workers May to September, males May to October (Williams et al. 2014). In Utah, queens reported April to October, workers and males May to September (Koch et al. 2012); in California, queens late March to late August, workers late April to late September, males late May to late September (Thorp et al. 1983).

Diagnostic Characteristics

Please see the

Montana State Entomology Collection's Key to Female Bumble Bees in Montana. Females told from other Montana

Bombus by a combination of outer surface of hind-leg tibia concave and hairless (except fringe) forming pollen basket; cheek distinctly longer than wide; face with pale yellow or white hairs, sometimes with black hairs intermixed giving cloudy appearance; T2 and/or T3 with yellow or black hairs, T3-4 orange (or T3-4 black); scutum of thorax (anterior to wing bases) cloudy with black and yellow hairs intermixed.

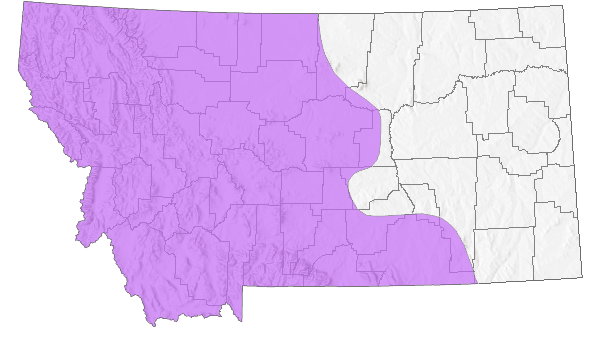

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Recorded Montana Distribution

Click the map for additional distribution information.

Range Comments

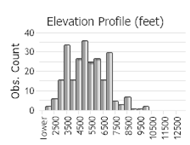

Western North America west of the Great Plains from northern Alaska, Yukon, and Northwest Territories south to southern California and New Mexico; east in arctic and boreal Canada to northern Manitoba and Ontario (Williams et al. 2014). Reported in California from 2440-3660 m elevation (Thorp et al. 1983); in Colorado, from 2400-4200 m elevation (Macior 1974). In the Uinta Mountains, Utah, found to at least 3320 m elevation (Bowers 1985); in the Beartooth Mountains of Montana, to at least 3050 m elevation (Bauer 1983). Common throughout its range (Koch et al. 2012, Williams et al. 2014).

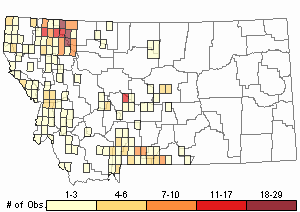

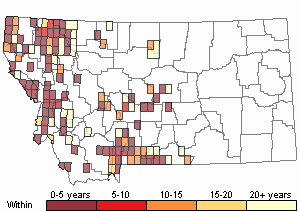

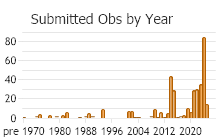

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 468

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Grasslands, prairies, riparian woodlands, aspen parkland, montane meadows, above treeline in alpine tundra (Hobbs 1967, Macior 1974, Richards 1978, Bauer 1983, Bowers 1985, Mayer et al. 2000, Kearns and Oliveras 2009, Wilson et al. 2010, Miller-Struttmann and Galen 2014, Williams et al. 2014). Also croplands of commercial Vaccinium fruit (Ratti et al. 2008).

Food Habits

Feeds on a variety of flowers, including Aconitum, Agastache, Allium, Aster, Astragalus, Calypso, Castilleja, Chamerion, Chionophila, Chrysothamnus, Cirsium, Delphinium, Dodecatheon, Epilobium, Erigeron, Eriogonum, Frasera, Gentiana, Geranium, Grindelia, Haplopappus, Helianthella, Helianthus, Iris, Lathyrus, Linaria, Lupinus, Mentha, Mertensia, Microseris, Mimulus, Onosmodium, Oxytropis, Pedicularis, Penstemon, Phacelia, Phlox, Polemonium, Polygonum, Primula, Rhododendron, Ribes, Rudbeckia, Sedum, Senecio, Sisyrinchium, Solidago, Symphoricarpos, Symphyotrichum, Taraxacum, Thermopsis, Trifolium, Vaccinium, Vicia and Viguiera (Beattie et al. 1973, Macior 1974, Schmitt 1980, Ackerman 1981, Bauer 1983, Thorp et al. 1983, Shaw and Taylor 1986, Mayer et al. 2000, Ratti et al. 2008, Wilson et al. 2010, Pyke et al. 2012, Koch et al. 2012, Miller-Struttmann and Galen 2014, Williams et al. 2014, Ogilvie and Thomson 2015). A significant pollinator of commercial highbush blueberry and cranberry (Vaccinium corymbosum and V. macrocarpon) in southern British Columbia (Ratti et al. 2008).

Reproductive Characteristics

Nests built mostly underground, rarely on the ground surface. Nests are initiated from mid May to early July. In prairie and mountain woodlands of southern Alberta 89.2% of 37 nests were underground, 10.8% on the ground surface and none above ground. In aspen parkland of southern Alberta 87% of 31 nests built below ground, 3.2% on the ground surface, and 12.9% above ground; queens camouflage entrance tunnels to their underground nests with grass or soil (Hobbs 1967, Richards 1978). Average number of eggs, larvae, and pupae in first broods is 8.2, 8.6, and 9.0, respectively; a single egg is laid in each egg cell. The largest colony with later broods contained 204 larvae (cocoons). Males patrol circuits in search of queens. Autumn queens excavate hibernacula in damp ground on steep north or west slopes, where they overwinter. In hibernation cages hibernacula were 3.8-10.2 cm deep; shallower hibernacula were excavated in compacted soil, deeper hibernacula in loose earth (Hobbs 1967). Probably parasitized by the cuckoo bumble bees Bombus fernaldae and B.suckleyi, a known host for B. insularis (Plath 1934, Hobbs 1967, Williams et al. 2014).

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Ackerman, J.D. 1981. Pollination biology of Calypso bulbosa var. occidentalis (Orchidaceae): a food-deception system. Madroño 28(3): 101-110.

Ackerman, J.D. 1981. Pollination biology of Calypso bulbosa var. occidentalis (Orchidaceae): a food-deception system. Madroño 28(3): 101-110. Bauer, P.J. 1983. Bumblebee pollination relationships on the Beartooth Plateau tundra of Southern Montana. American Journal of Botany. 70(1): 134-144.

Bauer, P.J. 1983. Bumblebee pollination relationships on the Beartooth Plateau tundra of Southern Montana. American Journal of Botany. 70(1): 134-144. Beattie, A.J., D.E. Breedlove, and P.R. Ehrlich. 1973. The ecology of the pollinators and predators of Frasera speciosa. Ecology 54: 81-91.

Beattie, A.J., D.E. Breedlove, and P.R. Ehrlich. 1973. The ecology of the pollinators and predators of Frasera speciosa. Ecology 54: 81-91. Bowers, M.A. 1985. Bumble bee colonization, extinction, and reproduction in subalpine meadows in northeastern Utah. Ecology 66(3): 914-927.

Bowers, M.A. 1985. Bumble bee colonization, extinction, and reproduction in subalpine meadows in northeastern Utah. Ecology 66(3): 914-927. Hobbs, G.A. 1967. Ecology of species of Bombus Latr. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in southern Alberta. VI. Subgenus Pyrobombus. Canadian Entomologist 99: 1271-1292.

Hobbs, G.A. 1967. Ecology of species of Bombus Latr. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in southern Alberta. VI. Subgenus Pyrobombus. Canadian Entomologist 99: 1271-1292. Kearns, C.A. and D.M. Oliveras. 2009. Boulder County bees revisited: a resampling of Boulder Colorado bees a century later. Journal of Insect Conservation 13: 603-613.

Kearns, C.A. and D.M. Oliveras. 2009. Boulder County bees revisited: a resampling of Boulder Colorado bees a century later. Journal of Insect Conservation 13: 603-613. Koch, J., J. Strange, and P. Williams. 2012. Bumble bees of the western United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 143 p.

Koch, J., J. Strange, and P. Williams. 2012. Bumble bees of the western United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 143 p. Macior, L.M. 1974. Pollination ecology of the Front Range of the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Melanderia 15: 1-59.

Macior, L.M. 1974. Pollination ecology of the Front Range of the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Melanderia 15: 1-59. Mayer, D.F., E.R. Miliczky, B.F. Finnigan, and C.A. Johnson. 2000. The bee fauna (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of southeastern Washington. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 97: 25-31.

Mayer, D.F., E.R. Miliczky, B.F. Finnigan, and C.A. Johnson. 2000. The bee fauna (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of southeastern Washington. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 97: 25-31. Miller-Struttmann, N.E. and C. Galen. 2014. High-altitude multi-taskers: bumble bee food plant use broadens along an altitudinal productivity gradient. Oecologia 176:1033-1045.

Miller-Struttmann, N.E. and C. Galen. 2014. High-altitude multi-taskers: bumble bee food plant use broadens along an altitudinal productivity gradient. Oecologia 176:1033-1045. Ogilvie, J.E. and J.D. Thomson. 2015. Male bumble bees are important pollinators of a late-blooming plant. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 9:205-213.

Ogilvie, J.E. and J.D. Thomson. 2015. Male bumble bees are important pollinators of a late-blooming plant. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 9:205-213. Plath, O.E. 1934. Bumblebees and their ways. New York, NY: Macmillan Company. 201 p.

Plath, O.E. 1934. Bumblebees and their ways. New York, NY: Macmillan Company. 201 p. Pyke, G.H., D.W. Inouye, and J.D. Thomson. 2012. Local geographic distributions of bumble bees near Crested Butte, Colorado: competition and community structure revisited. Environmental Entomology 41(6): 1332-1349.

Pyke, G.H., D.W. Inouye, and J.D. Thomson. 2012. Local geographic distributions of bumble bees near Crested Butte, Colorado: competition and community structure revisited. Environmental Entomology 41(6): 1332-1349. Ratti, C.M., H.A. Higo, T.L. Griswold, and M.L. Winston. 2008. Bumble bees influence berry size in comercial Vaccinium spp. cultivation in British Columbia. Canadian Entomologist 140(3): 348-363.

Ratti, C.M., H.A. Higo, T.L. Griswold, and M.L. Winston. 2008. Bumble bees influence berry size in comercial Vaccinium spp. cultivation in British Columbia. Canadian Entomologist 140(3): 348-363. Richards, K.W. 1978. Nest site selection by bumble bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in southern Alberta. Canadian Entomologist 110(3): 301-318.

Richards, K.W. 1978. Nest site selection by bumble bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in southern Alberta. Canadian Entomologist 110(3): 301-318. Schmitt, J. 1980. Pollinator foraging behavior and gene dispersal in Senecio (Compositae). Evolution 34: 934-943.

Schmitt, J. 1980. Pollinator foraging behavior and gene dispersal in Senecio (Compositae). Evolution 34: 934-943. Shaw, D.C. and R.J. Taylor.1986. Pollination ecology of an alpine fell-field community in the North Cascades. Northwest Science 60:21-31.

Shaw, D.C. and R.J. Taylor.1986. Pollination ecology of an alpine fell-field community in the North Cascades. Northwest Science 60:21-31. Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79.

Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79. Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p.

Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p. Wilson, J.S., L.E. Wilson, L.D. Loftis, and T. Griswold. 2010. The montane bee fauna of north central Washington, USA, with floral associations. Western North American Naturalist 70(2): 198-207.

Wilson, J.S., L.E. Wilson, L.D. Loftis, and T. Griswold. 2010. The montane bee fauna of north central Washington, USA, with floral associations. Western North American Naturalist 70(2): 198-207.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Burkle L.A., M.P. Simanonok, J.S. Durney, J.A. Myers, and R.T. Belote. 2019. Wildfires influence abundance, diversity, and intraspecific and interspecific trait variation of native bees and flowering plants across burned and unburned landscapes. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 7(252):1-14.

Burkle L.A., M.P. Simanonok, J.S. Durney, J.A. Myers, and R.T. Belote. 2019. Wildfires influence abundance, diversity, and intraspecific and interspecific trait variation of native bees and flowering plants across burned and unburned landscapes. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 7(252):1-14. Delphia, C.M., Griswold, T., Reese, E.G., O'Neill, K.M., and Burkle, L.A. 2019. Checklist of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) from small, diversified vegetable farms in south-western Montana. Biodiversity Data Journal: e30062

Delphia, C.M., Griswold, T., Reese, E.G., O'Neill, K.M., and Burkle, L.A. 2019. Checklist of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) from small, diversified vegetable farms in south-western Montana. Biodiversity Data Journal: e30062 Dolan, A.C. 2016. Insects associated with Montana's huckleberry (Ericaceae: Vaccinium globulare) plants and the bumble bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) of Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 160 p.

Dolan, A.C. 2016. Insects associated with Montana's huckleberry (Ericaceae: Vaccinium globulare) plants and the bumble bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) of Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 160 p. Dolan, A.C., C.M. Delphia, K.M. O'Neill, and M.A. Ivie. 2017. Bumble Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) of Montana. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 110(2): 129-144.

Dolan, A.C., C.M. Delphia, K.M. O'Neill, and M.A. Ivie. 2017. Bumble Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) of Montana. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 110(2): 129-144. Fultz, J.E. 2005. Effects of shelterwood management on flower-visiting insects and their floral resources. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 163 p.

Fultz, J.E. 2005. Effects of shelterwood management on flower-visiting insects and their floral resources. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 163 p. Kearns, C.A. and J.D. Thomson. 2001. The Natural History of Bumble Bees. Boulder, CO. University Press of Colorado.

Kearns, C.A. and J.D. Thomson. 2001. The Natural History of Bumble Bees. Boulder, CO. University Press of Colorado. Reese, E.G., L.A. Burkle, C.M. Delphia, and T. Griswold. 2018. A list of bees from three locations in the Northern Rockies Ecoregion (NRE) of western Montana. Biodiversity Data Journal 6: e27161.

Reese, E.G., L.A. Burkle, C.M. Delphia, and T. Griswold. 2018. A list of bees from three locations in the Northern Rockies Ecoregion (NRE) of western Montana. Biodiversity Data Journal 6: e27161. Simanonok, M. 2018. Plant-pollinator network assembly after wildfire. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 123 p.

Simanonok, M. 2018. Plant-pollinator network assembly after wildfire. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 123 p. Simanonok, M.P. and L.A. Burkle. 2019. Nesting success of wood-cavity-nesting bees declines with increasing time since wildfire. Ecology and Evolution 9:12436-12445.

Simanonok, M.P. and L.A. Burkle. 2019. Nesting success of wood-cavity-nesting bees declines with increasing time since wildfire. Ecology and Evolution 9:12436-12445. Simanonok, M.P., and L.A. Burkle. 2014. Partitioning interaction turnover among alpine pollination networks: Spatial temporal, and environmental patterns. Ecosphere 5(11):149.

Simanonok, M.P., and L.A. Burkle. 2014. Partitioning interaction turnover among alpine pollination networks: Spatial temporal, and environmental patterns. Ecosphere 5(11):149.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Yellow Head Bumble Bee"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Insects"