View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Moth Mullein - Verbascum blattaria

Other Names:

White Moth Mullein

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Verbascum blattaria is native to portions of Eurasia and was introduced into North America (Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018). A conservation status rank is not applicable (SNA) because Verbascum blattaria is a non-native vascular plant in Montana that is not a suitable target for conservation activities.

General Description

PLANTS: Course, biennial (occasionally annual) forbs that grow from a deep taproot and develop a single, erect simple or branched stem, 30-80 cm tall. Sources: DiTomaso et. 2013; Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018; Lesica et al. 2022

LEAVES: Basal leaves form a rosette, that is often pressed flat to the ground. Basal leaves are simple with petioles; blades are oblanceolate in shape, shallowly pinnately lobed or crenate, and 4-15cm long. Cauline leaves are simple, sessile (lack petiole), glabrous, alternately arranged, and reduced upwards on the stem. Stem leaf blades are lanceolate in shape with serrate margins. Sources: Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018; Lesica et al. 2022

INFLORESCENCE: A narrow, terminal raceme with bracts that subtend widely spaced showy yellow or white flowers. Radially symmetrical flowers have a pedicel, 5-15 mm and longer than the bract, and are solitary in the bract axils. Stem within inflorescence is glandular-puberulent. Sepals: 5, lanceolate, deeply divided but fused at base, and 5-7 mm long. Petals 5, fused,15-30 mm across. Stamens: 5, exserted, fertile. Filaments with long, soft, crooked, and unmatted purple hairs (villous). Anthers purple. Pistil: single with a capitate stigma. Sources: Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018; Lesica et al. 2022

TAXONOMY & NOMENCLATURE

The common name “Moth Mullein” is in reference to the soft petals, which resemble a moth’s wings, and the hairy stamens which suggests its legs (Cochran 1948). The specific epithet of blattaria is Latin for ‘cockroach’ or ‘moth’. Pliny (Gaius Plinius Secundus), a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, used the term “Verbascum” for “mullein” (Cochran 1948).

Phenology

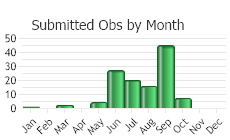

Flowering June to September (Gross and Werner 1978; Durham et al. 2017).

Diagnostic Characteristics

Montana’s two

Verbascum species can be distinguished by these characteristics:

Moth Mullein -

Verbascum blattaria, non-native

* Plants: Glabrous or puberulent; glandular.

* Leaves: Brighter green. Basal leaves flattened to ground. Lower stem leaves glabrous.

* Inflorescence: Glandular-hairy.

* Flowers: Pedicels, 5-15 mm long.

Common Mullein -

Verbascum thapsus, non-native, aggressive

* Plants: Densely hairy (tomentose). Lacks glands.

* Leaves: Gray-green. Basal leaves grow more upwards/outwards. Stem leaves velvety or wooly (tomentose) and long-decurrent.

* Inflorescence: Not glandular.

* Flowers: Sessile in little clusters.

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Non-native

Non-native

Range Comments

Moth Mullein is native to Eurasia (Lesica et al. 2022). Plants were introduced into North America, and now occur throughout the temperate portions of the continent.

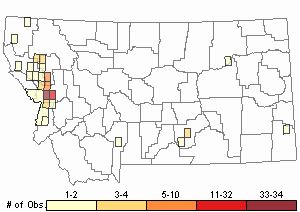

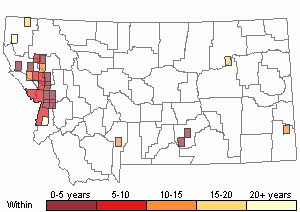

The earliest documented herbarium specimen was collected in Sanders County by J.W. Blankinship in 1901 (CPNWH 2025; CGPH 2025). By the late 1930s, plants were documented in Missoula, Lake, and Ravalli Counties (CPNWH 2025; CGPH 2025). Since then plants have been found in more places west of the Continental Divide in Montana. In 1974 and 1989, two vague reports by the same person were reported for Big Horn County (MTNHP botany database 2025). Otherwise, a scattering of observations in central and eastern Montana have all been reported since 2008 (MTNHP botany database 2025).

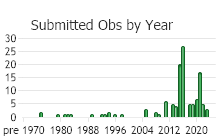

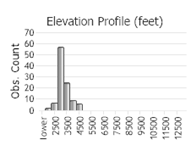

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 144

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Moth Mullein grows on disturbed, often stony soil of grasslands, streambanks, and roadsides in the plains and valley zones of Montana (Lesica et al. 2022). In addition, plants are found in rangeland, forest clearings, and meadows (Ditomaso et al. 2013). Plants prefer disturbed sites with well-drained soils; however, they are not limited to these conditions (Ditomaso et al. 2013).

Ecology

CULTURAL & MEDICINAL USESA methanol extract derived from Moth Mullein was shown to be effective against mosquito larvae (

Aedes aegypti L.), even at low concentrations (Gross and Werner 1978).

POLLINATORSThe following animal species have been reported as pollinators of this plant species or its genus where their geographic ranges overlap:

Bombus vagans,

Bombus ternarius, and

Bombus pensylvanicus (Colla and Dumesh 2010).

Reproductive Characteristics

Plants reproduce by seed.

FLOWERING

A study on phenology in 2013 found that Moth Mullein plants flowered from June 30th through September 30th in the Sapphire Mountains, east of Missoula, Montana (Durham et al. 2017). This study also demonstrated that exotic (non-native) plants emerged earlier, began and ended flowering later, and had later dates to emergence and dispersal phases for all functional groups (perennial forbs, perennial grasses, and short-lived forbs).

Floral biology for Moth Mullein is summarized by Gross and Werner (1978). The anthers and style of the pistil mature at the same time for Moth Mullein. The style protrudes from the corolla, enticing an insect to land before it enters the corolla to get nectar. Flowers can also self-pollinate. As the flower closes, the anthers adhere together under the stigma in such a way that pollen is transferred from anthers to stigma.

FRUITS

Fruit is a capsule. Capsule is glandular, broadly ellipsoid, 5-10 mm long, and 2-celled. At maturity, capsules open length-wise to disperse numerous seeds (Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018).

Seeds are dark brown and are more even-edged (Meehan 1884).

LIFE CYCLE [adapted from Gross and Werner (1978) and DiTomoso et al. (2013)]

Moth Mullein populations are ephemeral and require periodic disturbances to sustain populations. Without disturbance, other plant species that grow dense have the potential to displace Moth Mullein. Seedlings germinate in bare ground and establish after a disturbance. Upon being subjected to lower temperatures (winter), the plant produces a tall flower stalk of indeterminate growth. Flowering occurs in late June and continues into September or as long as conditions remain conducive. Within the raceme flowers bloom from bottom to top. By mid-season, the raceme may have mature capsules at the base and newly produced flowers at the top. Moth Mullein capsules split with the movement of wind or animals. It is presumed that most seeds land near to the parent plant. A mature plant can produce more than 100,000 seeds. Seeds in the soil can remain viable for 90 years (Toole 1986). A pint bottle placed into sand for 120 years, uncorked and tilted to prevent water accumulation, had viable seeds (Telewski and Zeevaart 2002).

Management

INTEGRATED VEGETATION MANAGEMENTAn integrated vegetative management approach provides the best long-term control, and requires that land-use objectives and a desired plant community be identified (Shelly et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Once identified, an integrated weed management strategy that promotes a weed-resistant plant community and serves other land-use objectives such as livestock forage, wildlife habitat, or recreation can be developed.

PREVENTION [Adapted from Piper in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Preventing the establishment of Moth Mullein is the most effective control method and fairly easy to accomplish by many practices:

* Learn how to accurately identify Moth Mullein in order to detect occurrences early and minimize invasions.

* Prevent vehicles from driving through, and animals from grazing within, infested areas.

* Thoroughly wash the undercarriage of vehicles and wheels in a designated area before moving to an un-infested area.

* Frequently monitor for new plants, and when found implement effective control methods.

* Maintain proper grazing management that creates resilience to noxious weed invasion.

* Plant or seed native species in barren areas, especially where sites are naturally and historically vegetated.

PHYSICAL and CULTURAL CONTROLS [Adapted from DiTomaso et al. 2013]

Hand-pulling plants before seed-set is effective, especially if growing on loose soil. When digging, sever the root below the soil surface to prevent flowering. Clipping the terminal raceme will cause the side branches to grow (Gross and Werner 1978). Soil disturbance stimulates recruitment. Hand-pulling is the most effective control method. Even if in the early phases of invasion, repeated hand-pulling can effectively remove plants over a couple of years. since plants only live

Mowing repeatedly during the bolting to early flowering stages can reduce seed production. Plants produce rosettes that cannot be effectively mowed and quickly regrow if mowing is discontinued.

Disking/Tillage is effective for controlling existing plants, but soil disturbance stimulates recruitment.

Fire is not an effective control. Fire stimulates, often dramatically, germination and establishment. Fire can be used to manage the seedbank, if seedlings are controlled with fire.

Revegetating with native or desirable plants is an effective control method. Populations are ephemeral. Therefore, with time populations usually decline unless periodically disturbed. Promoting competitive native or desirable plant species and reducing soil disturbance are the best control options. Native vegetation that shades and competes for early season moisture will be better at reducing Moth Mullein germination.

BIOLOGICAL CONTROLS Mullein Weevil (

Rhinusa tetra) specifically attacks both Common and Moth Mullein (Winston et al. 2014). The larvae mature within the seed capsules and destroy up to 50% of the seeds (DiTomaso et al. 2013). Mullein Weevil was accidentally introduced from Europe into the USA in 1919 from an unknown source (Winston et al. 2014). In 1995 it was deliberately re-distributed (Winston et al. 2014). As of 2014, Mullein Weevil is considered to be well-established in Washington, where it has been shown to cause extensive seed destruction. In Oregon it is widespread, but the impact is unknown. Mullein Weevil occurs in California, but has had little impact. In Montana, populations are limited and impacts are unknown.

Mullein Leaf Bug (

Campylomna verbasci) normally feeds on mullein plants. In Nova Scotia, Canada the Mullein Leaf Bug has caused extensive damage to apple and pear trees and potato leaves (Maw 1980; Pickett 1939).

CHEMICAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Harvey and Mangold 2018]

Herbicides may be effective, especially when properly managed with other tactics. The herbicide type and concentration, timing of chemical control, soil properties, and other factors will determine its effectiveness and impact to non-target species. Strict adherence to application requirements defined on the herbicide label will reduce risks to human and environmental health. Many herbicides must be applied by applicators with an Aquatic Pest Control license. Consult your County Extension Agent and/or Weed District for more information on herbicidal control.

Moth Mullein completes its life cycle in two years (biennial).

Herbicides should only be applied during the 1st year of growth when plants are in seedling, rosette, or very early bolting stages. DiTomaso et al. (2013) has summarized

chemical control for mullein species.

GRAZING CONTROLS Moth Mullein is considered unpalatable for domesticated livestock (Ditomaso et al. 2013).

PARASITESThree species of leaf-inhabiting parasitic fungi have been reported on Moth Mullein (Gross and Werner 1978).

Useful Links:Central and Eastern Montana Invasive Species TeamMontana Invasive Species websiteMontana Biological Weed Control Coordination ProjectMontana Department of Agriculture - Noxious WeedsMontana Weed Control AssociationMontana Weed Control Association Contacts WebpageMontana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks - Noxious WeedsMontana State University Integrated Pest Management ExtensionWeed Publications at Montana State University Extension - MontGuides

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Moth Mullein can rapidly form dense stands in disturbed areas (DiTomaso et al. 2013). In rangelands it invades over-grazed, sparsely vegetated, or barren land while providing no nutritional forage for livestock or native ungulates. Moth Mullein appears to be expanding into central and eastern Montana. However, it is unknown if reported populations are persisting and/or increasing in numbers or areal extent. More data on control efforts, population extent, and plant counts are needed.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68.

Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68. DiTomaso, Joe M., and G.B. Kyser. 2013. A Weed Report from Weed Control in Natural Areas in the Western United States. Weed Research and Information Center, University of California. 544 pp.

DiTomaso, Joe M., and G.B. Kyser. 2013. A Weed Report from Weed Control in Natural Areas in the Western United States. Weed Research and Information Center, University of California. 544 pp. Durham, R. A., D. L. Mummey, L. Shreading, and P.W. Ramsey. 2017. Phenological patterns differ between exotic and native plants: Field observations from the Sapphire Mountains, Montana. Natural Areas Journal, 37(3), 361–381.

Durham, R. A., D. L. Mummey, L. Shreading, and P.W. Ramsey. 2017. Phenological patterns differ between exotic and native plants: Field observations from the Sapphire Mountains, Montana. Natural Areas Journal, 37(3), 361–381. Gross, Katherine L., and Patricia A. Werner. 1978. The Biology of Canadian Weeds. 28. Verbascum thapsus L. and V. blattaria L. Can. J. Plant Sci. 58: 401-413

Gross, Katherine L., and Patricia A. Werner. 1978. The Biology of Canadian Weeds. 28. Verbascum thapsus L. and V. blattaria L. Can. J. Plant Sci. 58: 401-413 Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Second Edition. Giblin, D.E., B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead (eds). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 882 p.

Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Second Edition. Giblin, D.E., B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead (eds). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 882 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Telewski, Frank W., and Jan A.D. Zeevaart. 2002. The 120-year period for Dr. Beal's Seed Viability Experiment. American Journal of Botany 89(8): 1285-1288.

Telewski, Frank W., and Jan A.D. Zeevaart. 2002. The 120-year period for Dr. Beal's Seed Viability Experiment. American Journal of Botany 89(8): 1285-1288. Toole, Vivian K. 1986. Ancient Seeds: Seed Longevity. Journal of Seed Technology. Volume 10, Number 1, pp. 1-23.

Toole, Vivian K. 1986. Ancient Seeds: Seed Longevity. Journal of Seed Technology. Volume 10, Number 1, pp. 1-23. Winston, R.L., M Schwarzlander, H.L. Hinz, M.D. Day, M.J.W. Cock, and M.H. Julien, Eds. 2014. Biological Control of Weeds: A World Catalogue of Agents and Their Target Weeds, 5th edition. USDA Forest Service, Forest health Technology Enterprise team, Morgantown, West Virginia. FHTET-2014-04. 838 pp.

Winston, R.L., M Schwarzlander, H.L. Hinz, M.D. Day, M.J.W. Cock, and M.H. Julien, Eds. 2014. Biological Control of Weeds: A World Catalogue of Agents and Their Target Weeds, 5th edition. USDA Forest Service, Forest health Technology Enterprise team, Morgantown, West Virginia. FHTET-2014-04. 838 pp.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Cope, M.G. 1992. Distribution, habitat selection and survival of transplanted Columbian Sharp-tailed Grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus columbianus) in the Tobacco Valley, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 60 p.

Cope, M.G. 1992. Distribution, habitat selection and survival of transplanted Columbian Sharp-tailed Grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus columbianus) in the Tobacco Valley, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 60 p. Forcella, Frank, and Stephen J. Harvey. 1988. Patterns of Weed Migration in Northwestern U.S.A. Weed Science. Volume 36:-194-201.

Forcella, Frank, and Stephen J. Harvey. 1988. Patterns of Weed Migration in Northwestern U.S.A. Weed Science. Volume 36:-194-201. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Quire, R.L. 2013. The sagebrush steppe of Montana and southeastern Idaho shows evidence of high native plant diversity, stability, and resistance to the detrimental effects of nonnative plant species. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 124 p.

Quire, R.L. 2013. The sagebrush steppe of Montana and southeastern Idaho shows evidence of high native plant diversity, stability, and resistance to the detrimental effects of nonnative plant species. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 124 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Moth Mullein"