View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Tansy Ragwort - Senecio jacobaea

Other Names:

Stinking Willie,

Jacobaea vulgaris

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Senecio jacobaea is a plant native to Europe and Asia Minor that has been introduced in northwestern and northeastern North America (FNA 2006; Coombs et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999). A conservation status rank is not applicable (SNA) because the plant is an exotic (non-native) in Montana that is not a suitable target for conservation activities.

NOTE: There is a large discrepancy between the number of observations and counties represented in the herbaria (Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria; www.pnwherbaria.org) versus the Montana Natural Heritage Program databases, which indicates a problem. It is important to document new occurrences with nice quality plant specimens of which some should be deposited in our State herbaria (University of Montana, Montana State University, Montana State University-Billings). Depositing specimens in the herbaria allows identifications to be confirmed, provides a central location for educating and sharing information, and allows specimens to be studied for genetics, morphology, and ecology.

General Description

PLANTS: Short-lived, taprooted perennial forb. Stems are erect, 20–80 cm tall. When young plants (especially leaves) may have a web-like pubescence (arachnoid). Sources: Coombs et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999; Lesica et al. 2012.

LEAVES: Leaves of the basal rosette are about 5-26 cm long, irregularly lobed, with a terminal lobe that is larger than the lateral lobes. Leaves along the stem are alternatively arranged, many (10-20), 4–20 cm long with petioles, but become smaller and sessile upwards. Stem leaf blades are narrowly oblanceolate in outline and deeply divided into dentate lobes. The stems and petioles are often purplish. Crushed leaves have a rank odor. Sources: Coombs et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999; Lesica et al. 2012.

INFLORESCENCE: Corymbiform with 10 to 60 yellow flower heads. Each flower head has an involucre of about 4–6 mm tall and 1-2 cm wide and is composed of ray and disc florets. There are 10-16 outer ray florets with yellow ray petals (ligules) about 6–10 mm long. The central disk flowers have corollas 4–5 mm long. Fruits are achenes, 1–2 mm long, and minutely hairy (puberulent). Sources: Coombs et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999; Lesica et al. 2012.

Phenology

July through August (Coombs et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999)

Diagnostic Characteristics

In Montana

Senecio is the 7th largest genus for vascular plants.

Senecio contains 28 species of which 3 are Species of Concern, 2 are exotic, and 6 are Status Under Review. Below are some common look-alikes, and

it is recommended to identify your plants with a technical manual designed for Montana.

All

Senecio species in Montana exhibit:

* Yellow flowers. Some are yellow-“daisy-like” in appearance and some lack showy yellow petals.

* Involucre bracts do not overlap, but are narrow, in one-row (or series), and may be black-tipped.

* Plants have hairs, some exhibit cobwebby hairs.

Tansy Ragwort –

Senecio jacobaea, exotic and Noxious:

* A biennial to short-lived perennial – pull a mature plant to find a dark-colored taproot.

* Stem leaves similar in size. Upper stem leaves only a little smaller than the basal leaves.

* Flowers with showy, yellow petals. Flower have both yellow ray and disc florets.

* Leaves pinnately deeply-divided into lobes that are shallowly divided.

* Lobe tips of leaves are rounded (not pointed).

* Plants have

sparse tangled, cobwebby hairs (arachnoid.

Common Groundsel -

Senecio vulgaris, exotic:

* An annual – pull a mature plant to find a light-colored taproot.

* Leaves either gradually become smaller upwards along the stem

or not.

* Basal stem leaves are largest, becoming small towards the upper stem.

* Flowers are not showy because they lack yellow petals (lack ray florets and have disc florets).

* Leaves pinnately deeply divided into unequal, toothed lobes.

* Plants have sparse villous (long, soft, and crooked) hairs.

* From the side-view, flower heads are tubular-shaped.

Common Tansy –

Tanacetum vulgare, exotic and Noxious:

* Yellow flowers lack petals. Flowers have yellow disc florets and lack ray florets.

* Leaves pinnately deeply divided into equal-sized, sharp-toothed lobes.

* Plants have few hairs (glabrate).

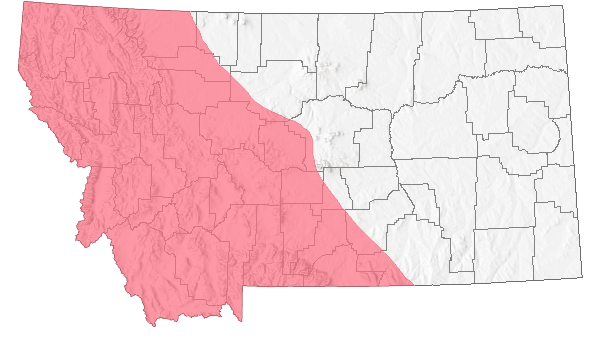

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Non-native

Non-native

Range Comments

Tansy Ragwort is native to the more temperature areas from Great Britain east to Siberia (Coombs et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Tansy Ragwort was first documented in North America in British Columbia in 1913. It may have been introduced to the U.S. as seed in ship ballast and/or contaminated straw. In 1992 it was documented along the Portland waterfront in Oregon. By the 1950’s it was a serious economic problem for stockmen west of the Cascades. The species is present in the northwestern and northeastern North America (FNA 2006: Lesica et al. 2012).

Tansy Ragwort was first document in Montana from a (1993 or 1994) burned clearcut in the Salish Mountains of Flathead County in 1995 (Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria; http://www.pnwherbaria.org). Herbarium specimens document it in Mineral, Sanders, and Flathead counties (www.pnwherbaria.org), but newer observations are finding it in many counties of western Montana [Refer to State Rank Reason and Observations In Montana Natural Heritage Program Database sections].

For maps and other distributional information on non-native species see:

Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Habitat Tool (INHABIT) from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Compendium from the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI)

EDDMapS Species Information EDDMapS Species Information

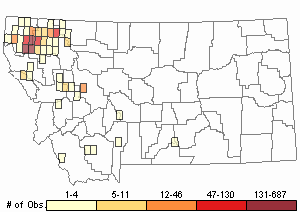

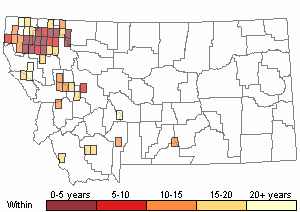

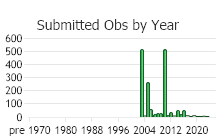

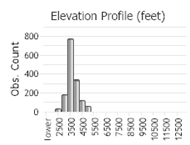

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 1754

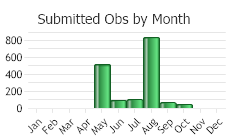

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

In its native habitat it grows in the meadows of oak and conifer woodlands, pastures, and along roadsides. In Montana it grows in disturbed soil of open forest and meadows of valleys that are often associated with timber harvest or fire (Lesica et al. 2012).

Ecology

Tansy Ragwort has a strong affinity to the Pacific Northwest because the climate is more similar to its native range in central Europe (Coombs et al.

in Sheley and Petroff 1999). It has particularly established well in habitats west of the Cascade Mountains, and is colonizing areas of the intermountain west that were previously thought to be unsusceptible. Many occurrences have been traced to an origin arising from either contaminated logging or hay equipment and transport from west of the Cascade Mountains (Ragweed Tansy’s ‘core area’). Spread has been facilitated by logging, over-grazing, road construction, and fire. Given disturbance Tansy Ragwort can dominate a site within 10 years.

East of the Cascade Mountains, Tansy Ragwort is generally found in Douglas-fir habitats at higher elevations where precipitation exceeds 16 to 20 inches (40-51 cm). It is thought that intact plant communities, sagebrush dominated communities, and sites with alkaline and desert soils are resistant to invasion. However, disturbed micro-habitats such as rodent burrows and ungulate tracks, can be sufficient for plants to colonize and persist. Invasions in Idaho and Montana indicate the importance of surveying northwest western forest and rangeland to detect plants early.

POLLINATORS The following animal species have been reported as pollinators of this plant species or its genus where their geographic ranges overlap:

Bombus bifarius,

Bombus flavifrons,

Bombus frigidus,

Bombus huntii,

Bombus melanopygus,

Bombus mixtus,

Bombus sylvicola,

Bombus occidentalis,

Bombus insularis,

Bombus suckleyi,

Bombus flavidus, and

Bombus kirbiellus (Schmitt 1980, Thorp et al. 1983, Mayer et al. 2000, Wilson et al. 2010, Pyke et al. 2012, Koch et al. 2012, Williams et al. 2014).

Reproductive Characteristics

Plants reproduce primarily from seeds, but can establish from buried vegetative buds (Coombs et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999).

FRUIT and SEEDS [Adapted from Coombs et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

The fruit is an achene that produces a single seed attached to its outer wall (shell). Achenes are 1–2 mm long and minutely hairy (puberulent). Achenes made from disc florets also have a tuft of hairs (pappus). Plants with multiple stems can produce more than 150,000 seeds. The persistence of viable seeds increases with the depth of burial in the soil. Viable seeds buried less than 2 cm generally do not germinate, but persist for at least 4-5 years. Viable seeds buried below 4 cm persisted in the soil for 10-16 years.

LIFE CYCLE [Adapted from Coombs et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Tansy Ragwort is a biennial or short-lived perennial that grows from a taproot. Seedlings germinate mostly in the spring and sometimes in the fall and develop into basal rosettes. The following spring in May to June the rosettes bolt, sending up single stem. Plants damaged by cutting or grazing may produce more stems from the root crown. Plants flower in June through October, depending upon moisture, temperature, and elevation. Flowering plants damaged by cutting or grazing will re-grow and re-flower later in the season or may just over-winter.

Fruits contain seeds which are produced from late summer to fall. The (outer) ray florets produce dark-colored, heavier fruits that are fewer in number and lack dispersal mechanisms. Fruits from ray florets remain longer in the flower head and disperse by falling close to the parent plant. The (central) disc florets produce more fruits that are smaller (about 2mm long) and light-brown. Each fruit has a tuft of hairs (pappus) which increases dispersal by air and has minute pubescence which helps it cling to animals for transport. Most fruits fall within 10 feet (3 meters) of their parent plant, and longer dispersals are usually aided by humans or other animals.

The density of rosettes is often higher than the population that matures. The size of seed bank will correlate with the number of past flowering plants. The rate of mortality declines with the stage of development. At study estimated that 57% of seedlings, 29% of single rosettes, 6% of multiple rosettes, and 8% of flowering plants die. The rate of death by juvenile plants increases when competing against perennial grasses and attacks by the Ragwort Flea Beetle (Longitarsus jacobaeae).

Management

Where large infestations are found, an integrative management approach will be needed and applied for many years to counteract Tansy Ragwort's persistence (Coombs et al.

in Sheley and Petroff 1999). New and isolated infestations must be eradicated promptly. A study in Oregon found that sites with more than 50 plants had a 50% chance of requiring continue treatment the following year. New infestations that have produced seeds may require several years of consecutive treatment. An integrated vegetative management approach provides the best long-term control, and requires that land-use objectives and a desired plant community be identified (Shelly et al.

in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Once identified then an integrated weed management strategy that promotes a weed-resistant plant community and serves other land-use objectives such as livestock forage, wildlife habitat, or recreation can be developed, making control of spotted knapweed possible (Shelly et al.

in Sheley and Petroff 1999).

PREVENTION [Adapted from Coombs et al.

in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Stopping the spread of Tansy Ragwort into uninfested areas is the most important and cost-effective technique. Logging, ranch and construction equipment and vehicles should be cleaned

before leaving ragwort-infested areas. Projects that rehabilitate lands after fire, logging, or construction should use certified weed-free seeds and weed-free hay. Areas treating infestations should be monitored for several consecutive years, even after no ragwort has been observed for two years.

PHYSICAL and CULTURAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Coombs et al.

in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Hand-pulling is effective for new or small infestations if done after plants have bolted, but before flowering. Removed plants should be bagged and allowed to desiccate before disposing or burned to destroy any seeds. However, plants in seed should not be pulled because it will likely cause seeds to spread and increase germination. Areas pulled should be seeded with desirable plants.

Mowing or

cutting is mostly ineffective because plants will produce lateral stems (re-sprouting from vegetative buds on the crown) that will still flower. If mowed, re-sprouted plants should be herbicided in the fall. Cutting stems before flowering will reduce seed production and will likely cause plants to grow more robust in the following spring.

Tilling annually can be effective to prevent plants from producing seed. Tilling stimulates seed germination, and if done frequently could be used to exhaust the seed bank in the soil.

Revegetation that establishes a desirable perennial plant community can compete against Tansy Ragwort. In pasture not managed for native vegetation, vigorous forage can be developing by planting grasses with clover (

Trifolium spp.) to provide nitrogen, though sulfur and phosphorus will need to be added with fertilizers.

GRAZING CONTROLS [Adapted from Coombs et al.

in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Plants are toxic to cattle and horses; therefore, livestock should not be allowed to graze fields where Tansy Ragwort has been treated, whether by mowing, revegetation, or herbicides.

Sheep have been used on infested pastures because plants are not toxic to them. However, Tansy Ragwort often increases after sheep are removed, making pastures not suitable for placing cattle or horses.

CHEMICAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Coombs et al.

in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Herbicides are effective, especially when properly integrated with intensive pasture management. The herbicide type and concentration, application time and method, environmental constraints, land use practices, local regulations, and other factors will determine its effectiveness and impact to non-target species. Strict adherence to application requirements defined on the herbicide label will reduce risks to human and environmental health. Consult your County Extension Agent and/or Weed District for information on herbicidal control.

The following herbicides can be used to treat Tansy Ragwort infestations where clover is not planted. They are selective herbicides that damage broadleaf plants (dicots), but not grasses (monocots). Applying herbicides after spring growth begins is generally more effective. Using fall applications without a wetting agent will reduce damage to clover, if present.

2,4-D can be applied at 1.0-2.0 pounds acid equivalent (ae) per acre to plants before flowering.

Picloram at 0.25 pounds ae per acre at the flowering stage. It can also be used in the fall to control seedling growth because it has residual in the soil.

Dicamba at 1.0 pounds ae per acre can be applied at the flowering stage.

Metsulfuron at 0.6 ounce active ingredient per acre or

Escort at 1.0 ounce per acre can be used when Tansy Ragwort is active growing.

Combinations of herbicides have also been used:

2,4-D plus Dicamba at 2.0 quarts per acre;

Triclopyr plus 2,4-D at 1.5-2.0 quarts per acre;

BIOLOGICAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Coombs et al.

in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

The

Cinnabar Moth (

Tyria jacobaeae) was released in California in 1959 and only took a few years to spread within the Pacific Northwest. It produces one generation each year. In the spring, the red-and-black winged adults emerge from their overwintering pupae, mate, and the female lays eggs on Tansy Ragwort rosettes. The orange-and-black striped larvae defoliate bolting plants, often preventing flowering. At 4-7 weeks in age the larvae pupate in litter. The Cinnabar Moth is most destructive in large infestations. Sites above 3,000 feet or that have cool, rainy summers or have very cold winters are generally not suitable.

The

Ragwort Flea Beetle (

Longitarsus jacobaeae) was released in California in 1969 and has been re-distributed through the Pacific Northwest. It is responsible for significantly reducing Tansy Ragwort density, and is effective in low-density populations where there is at least one plant per square yard or meter. At Oregon Department of Agriculture study sites, flowering plant density declined 90% within six years following Ragwort Flea Beetle releases (McEvoy et al. 1991). This corresponded to a decline in livestock poisoning cases (Coombs et al. 1996b). The small, golden-brown adults mate and lay eggs on rosettes and in the soil near plants. Adults are most active in the fall after the first rains. Adults chew small holes in the leaves creating a “shot hole” appearance. Larvae feed on the roots causing mortality.

The

Ragwort Seed-head Fly (

Botanophila seneciella) was introduced in the U.S. in 1966, and has mostly on its own occupied the Pacific Northwest. The Ragwort Seedhead Fly appears similar to a house-fly, and is not that effective at controlling Tansy Ragwort populations. However, the Ragwort Seedhead Fly has occupied areas where the Cinnabar Moth and Ragwort Flea Beetle have not survived. In Oregon the Ragwort Seedhead Fly rarely attack more than 40% of the flowers. In the spring adults emerge, mate, and the females lay eggs on developing flower buds. Larvae hatch, tunnel into the involucres, and feed on the developing seeds and receptacle tissues. Flowers that are attached will develop a dark center and which layer exude a clear frothy spittle. Mature larvae leave the flower and pupate in the soil.

In 1990 the

Root-boring Moth (

Cochylis atricapitana) was released into Canada, but has not been approved for introduction into the U.S. The Root-boring Moth occupies inland sites in comparison to the Cinnabar Moth and Ragwort Flea Beetle.

Montana's Tansy Ragwort Task Force is led by Lincoln County Weed District at: (406) 283-2420

Useful Links:Central and Eastern Montana Invasive Species TeamMontana Invasive Species websiteMontana Biological Weed Control Coordination ProjectMontana Department of Agriculture - Noxious WeedsMontana Weed Control AssociationMontana Weed Control Association Contacts WebpageMontana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks - Noxious WeedsMontana State University Integrated Pest Management ExtensionWeed Publications at Montana State University Extension - MontGuidesStewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Tansy Ragwort contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids which are toxic to cattle and horses (Coombs et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Tansy Ragwort is mildly toxic to goats and does not appear to affect sheep. Leaves are the most toxic portion of the plant, averaging 0.18% of the weight of dry plants. The toxicity forms after the compounds are converted to pyrroles in the liver. Damage in the liver is cumulative. Cattle that have ingested 3-7% of their body weight in Tansy Ragwort generally die of liver failure. Poisoning has often occurred in the spring when grazing animals cannot selectively remove Tansy Ragwort from grass. Plants remain toxic in hay silage. Suckling animals may acquire the toxins through contaminated milk.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Koch, J., J. Strange, and P. Williams. 2012. Bumble bees of the western United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 143 p.

Koch, J., J. Strange, and P. Williams. 2012. Bumble bees of the western United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 143 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Mayer, D.F., E.R. Miliczky, B.F. Finnigan, and C.A. Johnson. 2000. The bee fauna (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of southeastern Washington. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 97: 25-31.

Mayer, D.F., E.R. Miliczky, B.F. Finnigan, and C.A. Johnson. 2000. The bee fauna (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of southeastern Washington. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 97: 25-31. Pyke, G.H., D.W. Inouye, and J.D. Thomson. 2012. Local geographic distributions of bumble bees near Crested Butte, Colorado: competition and community structure revisited. Environmental Entomology 41(6): 1332-1349.

Pyke, G.H., D.W. Inouye, and J.D. Thomson. 2012. Local geographic distributions of bumble bees near Crested Butte, Colorado: competition and community structure revisited. Environmental Entomology 41(6): 1332-1349. Schmitt, J. 1980. Pollinator foraging behavior and gene dispersal in Senecio (Compositae). Evolution 34: 934-943.

Schmitt, J. 1980. Pollinator foraging behavior and gene dispersal in Senecio (Compositae). Evolution 34: 934-943. Sheley, Roger, and Janet Petroff. 1999. Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon.

Sheley, Roger, and Janet Petroff. 1999. Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon. Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79.

Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79. Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p.

Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p. Wilson, J.S., L.E. Wilson, L.D. Loftis, and T. Griswold. 2010. The montane bee fauna of north central Washington, USA, with floral associations. Western North American Naturalist 70(2): 198-207.

Wilson, J.S., L.E. Wilson, L.D. Loftis, and T. Griswold. 2010. The montane bee fauna of north central Washington, USA, with floral associations. Western North American Naturalist 70(2): 198-207.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Crider, Kimberly K. 2010. Biological control: Effects of Tyria jacobaeae on the population dynamics of Senecio jacobaea in northwest Montana.

Crider, Kimberly K. 2010. Biological control: Effects of Tyria jacobaeae on the population dynamics of Senecio jacobaea in northwest Montana. Dillard, S.L. 2019. Restoring semi-arid lands with microtopography. M.Sc. Thesis. Bpzeman, MT: Montana State University. 97 p.

Dillard, S.L. 2019. Restoring semi-arid lands with microtopography. M.Sc. Thesis. Bpzeman, MT: Montana State University. 97 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Maxwell, B.D. 1984. Changes in an infested plant community after an application of picloram, the effect of glyphosate on bud dormancy, the effect of pulling and the fuel potential of leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula L.). M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 73 p.

Maxwell, B.D. 1984. Changes in an infested plant community after an application of picloram, the effect of glyphosate on bud dormancy, the effect of pulling and the fuel potential of leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula L.). M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 73 p. Olliff, Tom, Roy Renkin, Craig McClure, Paul Miller, Dave Price, Dan Reinhart, and Jennifer Whipple. 2001. Managing A Complex Exotic Vegetation Program in Yellowstone National Park.

Olliff, Tom, Roy Renkin, Craig McClure, Paul Miller, Dave Price, Dan Reinhart, and Jennifer Whipple. 2001. Managing A Complex Exotic Vegetation Program in Yellowstone National Park.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Tansy Ragwort"