View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

White Sweetclover - Melilotus albus

Non-native Species

Global Rank:

G5

State Rank:

SNA

(see State Rank Reason below)

C-value:

0

Agency Status

USFWS:

USFS:

BLM:

External Links

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Melilotus albus is native to Europe and western Asia and was introduced into North America (Turkington et al. 1978). A conservation status rank is not applicable (SNA) because the plant is an exotic (non-native) in Montana and is not a suitable target for conservation activities.

General Description

PLANTS: Erect, single-stemmed, herbaceous biennial (sometimes annual or perennial) from a taproot. Herbage nearly glabrous and 50 to 100 cm tall. Sources: Hitchcock et al. 2018; Lesica et al. 2012.

LEAVES: Leaves alternate and trifoliate. Leaflets oblong, 1-3 cm long, typically smooth, and serrated almost to the base. Sources: Hitchcock et al. 2018; Lesica et al. 2012.

INFLORESCENCE: Inflorescence is of many narrow, minutely bracteate (2 mm), elongated, spike-like racemes 5-16 cm long, arising in the leaf axils and supporting 20-80 nodding flowers. Flowers are pea-like, strongly sweet-scented, 3-4(-5.5) mm long, nodding, and white. Wing petals about equal in length as the keel petal. Calyx is about 2 mm long. Fruit is an ovoid legume, about 3 mm long, scarcely dehiscent, and mostly containing one seed. A single plant can produce thousands of viable seeds. Sources: Hitchcock et al. 2018; Lesica et al. 2012.

The genus Melilotus comes from meli, which is the Greek word for honey, and lotus which refers to a 'clover-like plant'.

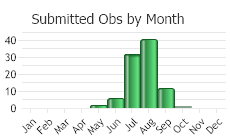

Phenology

Flowering in early summer through fall (Gucker 2009).

Diagnostic Characteristics

White Sweetclover – Melilotus albus, exotic

* Flowers: white.

* Racemes: greater than 4 cm long. At peak flowering racemes are 8-15 times as long as wide.

* Leaflets: 3. Margins serrated more than half-way to the base. Leaflets 2.5-3.5 times as long as broad.

* Fruits (legume): surface has shorter ridges (veins) that delimit spaces (areolae), and these spaces tend to be as long as wide (more squarish).

* Habitat: In Montana there is a tendency for White Sweetclover to grow more commonly in riparian areas and in slightly moister sites.

Yellow Sweetclover –

Melilotus officinalis* Flowers: yellow.

* Racemes: greater than 4 cm long. At peak flowering racemes are 6 times as long as wide.

* Leaflets: 3. Margins serrated more than half-way to the base. Leaflets usually no more than 2 times longer than broad.

* Fruits (legume): surface has elongated ridges (veins) that delimit spaces (areolae), and these spaces tend to be longer than wide.

Alfalfa –

Medicago sativa* Flowers: purple or white.

* Racemes: less than 3 cm long.

* Fruits (legume): surface texture is veiny; coiled or curved with more than one seed.

* Leaflets: 3. Margins serrated in upper half of leaflet. Oblanceolate.

TAXONOMYYellow Sweetclover and White Sweetclover share similar appearances, except for their flower color, which has caused many botanists to conclude they are of the same species (conspecific) (Kartesz 2015; USDA PLANTS Database [NRCS 2022]; IT IS 2017; Bugwood 2017). However, Darbyshire and Small (2018) report evidence that these two species are evolutionarily separate and genetically more closely related to other species in the genus than they are to each other. Breeding studies have shown that there are strong physiological barriers to fertilization, and when crossed Yellow and White Sweetclovers rarely produce fertile progeny (Darbyshire and Small 2018). Differences found in their phenology, ecology, physiology/biochemistry, seed protein profiles, chromosome structure, and DNA sequences support the theory that they evolved separately from one another (Darbyshire and Small 2018). Hence, Darbyshire and Small (2018) support the treatment that Yellow Sweetclover and White Sweetclover are separate species.

NOMENCLATUREThe International Code of Nomenclature sets the rules and recommendations that govern the scientific naming of plants, fungi, and algae (https://www.iapt-taxon.org/nomen/main.php; formerly called the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature). According to the rules

Melilotus is treated as masculine, and therefore the specific epithet must be '

albus.

Melilotus has incorrectly been treated as feminine resulting in the scientific name of

Melilotus alba.

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Non-native

Non-native

Range Comments

White Sweetclover is native to Europe and western Asia (Turkington et al. 1978). White Sweetclover is considered naturalized throughout Europe and Asia eastward to Tibet and also in Australia, South Africa, and Argentina (Turkington et al. 1978).

Melilotus was first reported in North America in 1664.

The earliest Montana herbarium specimen on the Consortium of the Pacific Northwest Herbaria portal was collected from Helena in 1892 (accessed on May 14, 2022 from (https://www.pnwherbaria.org).

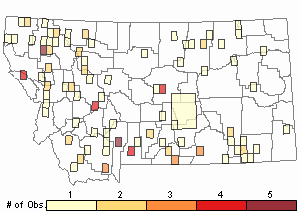

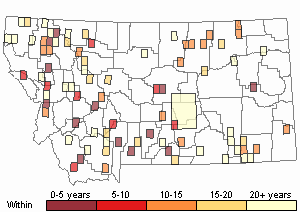

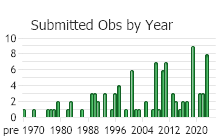

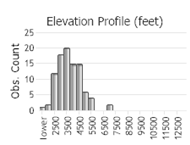

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 165

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Open roadsides, fields, and streambanks in the plains and valley zones of Montana (Lesica et al. 2012).

White Sweetclover tends to be more common along streams and in moister habitats than Yellow Sweetclover (Lesica et al. 2012).

Ecology

POPULATION CONTROLSWhite Sweetclover has been shown to increase with disturbance while some native species declined (Parker et al. 1993). In one study, White Sweetclover grew to a height of 1.5 meters in disturbed sites, shading native species, thus potentially reducing light to lower growing natives (Parker et al. 1993). Changes to soil conditions (e.g. compaction, change in mineral composition) in disturbed areas may also be a reason for why White Sweetclover proliferates over native species. In undisturbed native areas White Sweetclover was shown to not compete as well.

POLLINATORSBees (honeybees, bumble bees, and leaf-cutter bees) are the most common pollinators of sweetclover (Gucker 2009). Wasps, flies, and other insects are less common pollinators (Gucker 2009).

The following insect species have been reported as pollinators of White Sweetclover or other

Melilotus species where their geographic ranges overlap:

Bombus vagans,

Bombus appositus,

Bombus bifarius,

Bombus borealis,

Bombus centralis,

Bombus fervidus,

Bombus huntii,

Bombus nevadensis,

Bombus rufocinctus,

Bombus sylvicola,

Bombus ternarius,

Bombus terricola,

Bombus occidentalis,

Bombus bimaculatus,

Bombus griseocollis,

Bombus impatiens,

Bombus insularis,

Bombus suckleyi,

Bombus bohemicus, and

Bombus flavidus (Macior 1974, Thorp et al. 1983, Johnson 1986, Colla and Dumesh 2010, Wilson et al. 2010, Colla et al. 2011, Koch and Strange 2012, Koch et al. 2012, Williams et al. 2014, Miller-Struttmann and Galen 2014).

Reproductive Characteristics

Plants reproduce by seed.

FLOWERS

Perfect (containing male and female organs). Calyx lobes are subequal, about 2 mm long. The sweet-scented pea-like flowers are bilaterally symmetrical, white, and 3-4(-5.5) mm long, with 10 stamens (9 united and 1 separate).

FRUITS

Ovoid legume, 3-4 mm long, scarcely dehiscent, and mostly containing one seed. A single plant can produce thousands of viable seeds.

LIFE CYCLE

White Sweetclover is primarily a biennial, however, it has been observed as annual, making it a facultative (rather than obligate) biennial. Plants germinate in spring. During the first season of growth, a single, branched, vegetative stem emerges while below ground a taproot develops. In the second year, numerous branched stems develop. Flowering commences in early summer and may continue throughout the growing season. Seeds develop from mid-summer to fall. Melilotus generally produces both readily germinable and water-impermeable or "hard" seeds; the latter capable of persisting in the seed bank for a decade or more and requiring scarification to germinate (Gucker 2009).

As is the case with many annual and biennial species, population sizes vary greatly from year to year and depend upon climatic conditions.

In White Sweetclover, bolting is positively correlated with the diameter of basal rosette (Baskin and Baskin 1979; Klemow and Raynal 1981).

Management

From an agricultural perspective Yellow Sweetclover and White Sweetclover have many uses while also can be problematic for farmers, livestock management, and in restoration.

CULTIVATIONThe planting and use of Melilotus species has been widely promoted for soil/roadside stabilization and reclamation, production of high-protein hay and forage, production of honey, and a host of other uses. Yellow Sweetclover is less often used as an agricultural crop compared to White Sweetclover (Turkington et al. 1978).

Sweetclovers that grow in wheat fields can cause sweetclover taint, whereby harvested wheat absorbs the characteristic odor of sweetclover (Turkington et al. 1978). This happens when sweetclover is still green or conditions are wet during wheat harvesting.

GRAZING MANAGEMENTYellow and White Sweetclovers are high in coumarin which causes anticoagulation of the blood (Whitson et al. 1996). This compound can cause bloat in cattle (Whitson et al. 1996). Feeding cattle spoiled sweetclover hay can cause sweetclover disease or 'bleeding disease' (Turkington et al. 1978). Commercially available varieties of these species planted for forage have been developed to produce lower levels of coumarin and are less likely to cause bloat (Whitson et al. 1996).

FIRE MANAGEMENT AND MOWINGWhite Sweetclover has become a serious problem in native grassland communities. Prescribed burning of infested areas to control sweetclovers produces variable results (Heitlinger 1975; Kline 1984). Spring burning may promote or inhibit seed germination, depending on the phenologic stage of plants at the time of burn. One study suggested that the follow tactics should suppress sweetclover: burning annually after second-year shoots are clearly visible; burning every other year before second-year plants ripen seed; and possibly by burning annually in late summer near the beginning of the critical growth period (Heitlinger 1975). Fall burns can have no effect or may even stimulate germination (Kline 1984). Mowing plants after bolting and before seed set was shown to be somewhat effective and could be used as a management tool when burning is not practical (Kline 1984). These efforts are aimed at reducing flowering and the subsequent prolific seed crop of this biennial species. Although these treatments may be effective, control of the species is problematic due to the high number and longevity of seeds in the seed bank (Kline 1984).

Useful Links:Montana Invasive Species websiteMontana Biological Weed Control Coordination ProjectMontana Department of Agriculture - Noxious WeedsMontana Weed Control AssociationMontana Weed Control Association Contacts Webpage.

Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks - Noxious WeedsMontana State University Integrated Pest Management ExtensionWeed Publications at Montana State University Extension - MontGuidesStewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

In more recent times, efforts have begun to control the sweetclover populations because they can have negative impacts to agricultural crops (associated with viral plant diseases), can quickly and abundantly invade natural habitats, shade native vegetation, alter soil nitrogen levels, and initiate shifts in native species composition (Gucker 2009).

In roadsides White Sweetclover plants can grow abundantly and very tall, often masking guard rails and road signs which creates potential problems for motorists (Turkington et al. 1978).

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Colla, S., L. Richardson, and P. Williams. 2011. Bumble bees of the eastern United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 103 p.

Colla, S., L. Richardson, and P. Williams. 2011. Bumble bees of the eastern United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 103 p. Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68.

Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68. Darbyshire, S. and E. Small. 2018. Are Melilotus albus and M. officinalis conspecific? Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 65:1571-1580.

Darbyshire, S. and E. Small. 2018. Are Melilotus albus and M. officinalis conspecific? Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 65:1571-1580. Gucker, C.L. 2009. Melilotus alba, M. officinalis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

Gucker, C.L. 2009. Melilotus alba, M. officinalis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Heitlinger, M.E. 1975. Burning a protected tallgrass prairie to suppress sweetclover, Melilotus alba Desr. pp. 123-132 In: M.K. Wali (ed). Prairie: A multiple view. Fargo, ND: University of North Dakota Press. 433 p.

Heitlinger, M.E. 1975. Burning a protected tallgrass prairie to suppress sweetclover, Melilotus alba Desr. pp. 123-132 In: M.K. Wali (ed). Prairie: A multiple view. Fargo, ND: University of North Dakota Press. 433 p. Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Second Edition. Giblin, D.E., B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead (eds). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 882 p.

Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Second Edition. Giblin, D.E., B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead (eds). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 882 p. International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen code). 2018. Adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress, Shenzhen, China. Regnum Vegetabile 159. Glashütten: Koeltz Botanical Books, Turland, N.J., Wiersema, J.H., Barrie, F.R., Greuter, W., Hawksworth, D.L., Herendeen, P.S., Knapp, S., Kusber, W.H., Li, D.Z., Marhold, K., May, T.W., McNeill, J., Monro, A.M., Prado, J., Price, M.J. & Smith, G.F. (eds.)

International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen code). 2018. Adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress, Shenzhen, China. Regnum Vegetabile 159. Glashütten: Koeltz Botanical Books, Turland, N.J., Wiersema, J.H., Barrie, F.R., Greuter, W., Hawksworth, D.L., Herendeen, P.S., Knapp, S., Kusber, W.H., Li, D.Z., Marhold, K., May, T.W., McNeill, J., Monro, A.M., Prado, J., Price, M.J. & Smith, G.F. (eds.) Johnson, R.A. 1986. Intraspecific resource partitioning in the bumble bees Bombus ternarius and B. pennsylvanicus. Ecology 67:133-138.

Johnson, R.A. 1986. Intraspecific resource partitioning in the bumble bees Bombus ternarius and B. pennsylvanicus. Ecology 67:133-138. Kartesz, J.T. 2015. The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) North American Plant Atlas. Chapel Hill, N.C. [maps generated from Kartesz, J.T. 2015. Floristic Synthesis of North America, Version 1.0. Biota of North America Program (BONAP). (in press)].

Kartesz, J.T. 2015. The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) North American Plant Atlas. Chapel Hill, N.C. [maps generated from Kartesz, J.T. 2015. Floristic Synthesis of North America, Version 1.0. Biota of North America Program (BONAP). (in press)]. Klemow, K.M. and D.J. Raynal. 1981. Population ecology of Melilotus alba in a limestone quarry. Journal of Ecology 69(1):33-44.

Klemow, K.M. and D.J. Raynal. 1981. Population ecology of Melilotus alba in a limestone quarry. Journal of Ecology 69(1):33-44. Kline, V.M. 1984. Response of sweet clover (Melilotus alba Desr.) and associated prairie vegetation to seven experimental burning and mowing treatments. In: Fire and Prairie Ecosystems, Proceedings of the Ninth North American Prairie Conf. pp. 149-152.

Kline, V.M. 1984. Response of sweet clover (Melilotus alba Desr.) and associated prairie vegetation to seven experimental burning and mowing treatments. In: Fire and Prairie Ecosystems, Proceedings of the Ninth North American Prairie Conf. pp. 149-152. Koch, J., J. Strange, and P. Williams. 2012. Bumble bees of the western United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 143 p.

Koch, J., J. Strange, and P. Williams. 2012. Bumble bees of the western United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 143 p. Koch, J.B. and J.P. Strange. 2012. The status of Bombus occidentalis and B. moderatus in Alaska with special focus on Nosema bombi incidence. Northwest Science 86:212-220.

Koch, J.B. and J.P. Strange. 2012. The status of Bombus occidentalis and B. moderatus in Alaska with special focus on Nosema bombi incidence. Northwest Science 86:212-220. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Macior, L.M. 1974. Pollination ecology of the Front Range of the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Melanderia 15: 1-59.

Macior, L.M. 1974. Pollination ecology of the Front Range of the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Melanderia 15: 1-59. Miller-Struttmann, N.E. and C. Galen. 2014. High-altitude multi-taskers: bumble bee food plant use broadens along an altitudinal productivity gradient. Oecologia 176:1033-1045.

Miller-Struttmann, N.E. and C. Galen. 2014. High-altitude multi-taskers: bumble bee food plant use broadens along an altitudinal productivity gradient. Oecologia 176:1033-1045. Parker, I.M., S.K. Mertens and D.W. Schemske. 1993. Distribution of seven native and two exotic plants in a tallgrass prairie in southeastern Wisconsin: the importance of human disturbance. The American Midland Naturalist 130(1):43-55.

Parker, I.M., S.K. Mertens and D.W. Schemske. 1993. Distribution of seven native and two exotic plants in a tallgrass prairie in southeastern Wisconsin: the importance of human disturbance. The American Midland Naturalist 130(1):43-55. Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79.

Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79. Turkington, R.A., P.B. Cavers, and E. Rempel. 1978. The biology of Canadian weeds. 29. Melilotus alba Desr. and M. officinalis (L.) Lam. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 58:523-537.

Turkington, R.A., P.B. Cavers, and E. Rempel. 1978. The biology of Canadian weeds. 29. Melilotus alba Desr. and M. officinalis (L.) Lam. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 58:523-537. USDA, NRCS. 2022. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 05/31/2022). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC USA.

USDA, NRCS. 2022. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 05/31/2022). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC USA. Whitson, T.D. (ed.), L.C. Burrill, S.A. Dewey, D.W. Cudney, B.E. Nelson, R.D. Lee, R. Parker. 1996. Weeds of the West. 5th edition. The Western Society of Weed Science in cooperation with the Western United States Land Grant Universities Cooperative Extension Services, Newark, CA. 630 pp.

Whitson, T.D. (ed.), L.C. Burrill, S.A. Dewey, D.W. Cudney, B.E. Nelson, R.D. Lee, R. Parker. 1996. Weeds of the West. 5th edition. The Western Society of Weed Science in cooperation with the Western United States Land Grant Universities Cooperative Extension Services, Newark, CA. 630 pp. Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p.

Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p. Wilson, J.S., L.E. Wilson, L.D. Loftis, and T. Griswold. 2010. The montane bee fauna of north central Washington, USA, with floral associations. Western North American Naturalist 70(2): 198-207.

Wilson, J.S., L.E. Wilson, L.D. Loftis, and T. Griswold. 2010. The montane bee fauna of north central Washington, USA, with floral associations. Western North American Naturalist 70(2): 198-207.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Boggs, K. W. 1984. Succession in riparian communities of the lower Yellowstone River, Montana. M.S. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman, 107 pp.

Boggs, K. W. 1984. Succession in riparian communities of the lower Yellowstone River, Montana. M.S. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman, 107 pp. Culver, D.R. 1994. Floristic analysis of the Centennial Region, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 199 pp.

Culver, D.R. 1994. Floristic analysis of the Centennial Region, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 199 pp. Dillard, S.L. 2019. Restoring semi-arid lands with microtopography. M.Sc. Thesis. Bpzeman, MT: Montana State University. 97 p.

Dillard, S.L. 2019. Restoring semi-arid lands with microtopography. M.Sc. Thesis. Bpzeman, MT: Montana State University. 97 p. Eggers, M.J.S. 2005. Riparian vegetation of the Montana Yellowstone and cattle grazing impacts thereon. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman, MT. 125 p.

Eggers, M.J.S. 2005. Riparian vegetation of the Montana Yellowstone and cattle grazing impacts thereon. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman, MT. 125 p. Fogelsong, M.L. 1974. Effects of fluorides on Peromyscus maniculatus in Glacier National Park. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 52 p.

Fogelsong, M.L. 1974. Effects of fluorides on Peromyscus maniculatus in Glacier National Park. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 52 p. Fritzen, D.E. 1995. Ecology and behavior of Mule Deer on the Rosebud Coal Mine, Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 143 p.

Fritzen, D.E. 1995. Ecology and behavior of Mule Deer on the Rosebud Coal Mine, Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 143 p. Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS 2017). May 17, 2022 last update from the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS) on-line database, www.itis.gov, https://doi.org/10.5066/F7KH0KBK

Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS 2017). May 17, 2022 last update from the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS) on-line database, www.itis.gov, https://doi.org/10.5066/F7KH0KBK Jones, W. W. 1901. Preliminary flora of Gallatin County. M.S. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State College. 78 pp.

Jones, W. W. 1901. Preliminary flora of Gallatin County. M.S. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State College. 78 pp. Law, D.J. 1999. A comparison of water table dynamics and soil texture under black cottonwood recent alluvial bar, beaked sedge, and Geyer's/Drummond's willow communities. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 68 p.

Law, D.J. 1999. A comparison of water table dynamics and soil texture under black cottonwood recent alluvial bar, beaked sedge, and Geyer's/Drummond's willow communities. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 68 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Lesica, P.L. and T.H. DeLuca. 2000. Sweetclover: A potential problem for the Northern Great Plains. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation; Ankeny 55(3): 259-261.

Lesica, P.L. and T.H. DeLuca. 2000. Sweetclover: A potential problem for the Northern Great Plains. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation; Ankeny 55(3): 259-261. Martinka, R.R. 1970. Structural characteristics and ecological relationships of male blue grouse (Dendragapus obscurus (Say)) territories in southwestern Montana. Ph.D Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 73 p.

Martinka, R.R. 1970. Structural characteristics and ecological relationships of male blue grouse (Dendragapus obscurus (Say)) territories in southwestern Montana. Ph.D Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 73 p. Quire, R.L. 2013. The sagebrush steppe of Montana and southeastern Idaho shows evidence of high native plant diversity, stability, and resistance to the detrimental effects of nonnative plant species. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 124 p.

Quire, R.L. 2013. The sagebrush steppe of Montana and southeastern Idaho shows evidence of high native plant diversity, stability, and resistance to the detrimental effects of nonnative plant species. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 124 p. Rundquist, V.M. 1973. Avian ecology on stock ponds in two vegetational types in north-central Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 112 p.

Rundquist, V.M. 1973. Avian ecology on stock ponds in two vegetational types in north-central Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 112 p. Sater, S. 2022. The insects of Sevenmile Creek, a pictorial guide to their diversity and ecology. Undergraduate Thesis. Helena, MT: Carroll College. 242 p.

Sater, S. 2022. The insects of Sevenmile Creek, a pictorial guide to their diversity and ecology. Undergraduate Thesis. Helena, MT: Carroll College. 242 p. Seipel, T.F. 2006. Plant species diversity in the sagebrush steppe of Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 87 p.

Seipel, T.F. 2006. Plant species diversity in the sagebrush steppe of Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 87 p. Skilbred, Chester L. 1979. Plant succession on five naturally revegetated strip-mined deposits at Colstrip, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 128 pp.

Skilbred, Chester L. 1979. Plant succession on five naturally revegetated strip-mined deposits at Colstrip, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 128 pp. Tuinstra, K. E. 1967. Vegetation of the floodplains and first terraces of Rock Creek near Red Lodge, Montana. Ph.D dissertation. Montana State University, Bozeman 110 pp.

Tuinstra, K. E. 1967. Vegetation of the floodplains and first terraces of Rock Creek near Red Lodge, Montana. Ph.D dissertation. Montana State University, Bozeman 110 pp. Zapatka, T.P. 1963. Some results of two limited hunting seasons on hen Pheasants in north central Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 26 p.

Zapatka, T.P. 1963. Some results of two limited hunting seasons on hen Pheasants in north central Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 26 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "White Sweetclover"