View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Common Sagebrush Lizard - Sceloporus graciosus

Native Species

Global Rank:

G5

State Rank:

S4

(see State Rank Reason below)

Agency Status

USFWS:

USFS:

BLM:

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is apparently secure and not at risk of extirpation or facing significant threats in all or most of its range.

General Description

EGGS:

The eggs are white, leathery, and oval. Typically, 13 mm (0.5 in) long and 8 mm (0.3 in) wide. Clutch sizes ranges from 3 to 5 eggs (Tinkle et al. 1993). Clutches are laid in loose soil in shallow cavities, often at the base of a shrub (Nussbaum et al. 1983, Hammerson 1999, Werner et al. 2004).

HATCHLINGS:

Hatchlings are 2.3 to 2.8 cm (0.91-1.1 in) snout-vent length (SVL) and are adult-like in appearance.

JUVENILES AND ADULTS:

The body is small and narrow with small spiny, keeled scales covering the back. Usually with a pale dorsolateral stripe on each side. Scales on the rear of the thigh are very small and often granular. Dorsal coloration is brown, olive or gray with a bluish or greenish tinge. The sides of the body and neck often have a rusty-orange hue. Ventral surfaces of females are white or yellow. Males have blue lateral abdominal patches and blue mottling on the throat. Maximum SVL is approximately 6.5 cm (2.56 in) and a maximum total length (TL) of 15 cm (5.9 in), with the tail length about 1.5 times the SVL. Mature males have enlarged postanal scales with two enlarged hemipenal swellings on the underside at the base of the tail. Gravid females may develop a reddish-orange color along the sides (Nussbaum et al. 1983, Koch and Peterson 1995, Hammerson 1999, St. John 2002, Werner et al. 2004).

Diagnostic Characteristics

The Common Sagebrush Lizard (

Sceloporus graciosus) lacks the broad flattened body and the fringe of prominent spines on each side of the body that is present in the Greater Short-horned Lizard (

Phrynosoma hernandesi), the only other Montana lizard with which it overlaps in range. It differs from the Western Fence Lizard (

Sceloporus occidentalis) by having pale dorsolateral stripes rather than a checkered pattern of darker triangular blotches in rows across the back. The dorsal scales of the Common Sagebrush Lizard are also less prickly and pointed and the blue throat patch in males is less pronounced. The Northern Alligator Lizard (

Elgaria coerulea) has a prominent skin fold on the side of the body. The Western Skink (

Plestiodon skiltonianus) has smooth shiny and flat dorsal scales, and juveniles and young skinks have conspicuous blue tails. Common Sagebrush Lizards have keeled or spiny scales, not flattened and shiny, and they never have a blue tail. Western Fence Lizard, Northern Alligator Lizard and Western Skink are found only in northwestern Montana, west of the Continental Divide (St. John 2002, Werner et al. 2004).

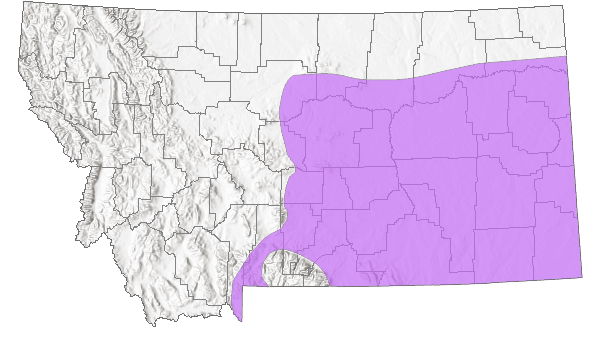

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Western Hemisphere Range

Range Comments

The Common Sagebrush Lizard is a member of a large genus of North American lizards found from Panama to the Canadian border. Three subspecies are currently recognized: the disjunct Dunes Sagebrush Lizard (S. g. arenicolous) of southeast New Mexico and adjacent Texas (Degenhardt and Jones 1972) has been elevated to full species status since Censky’s (1986) sagebrush lizard species account. Two subspecies are restricted to Pacific coastal states of the U.S. and Baja Peninsula of Mexico. The Northern Sagebrush Lizard (S. g. graciosus) occupies the majority of the species’ range, and occurs from northern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico, north through Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, eastern Oregon, central Washington and southern Idaho. It can be found at elevations to 3,200 m (10,500 ft) in the southwestern states (Nussbaum et al. 1983, Censky 1986) and reaching the northeastern limits of its range in Montana and North Dakota (Hoberg and Gause 1989, Maxell et al. 2003, Werner et al. 2004). In Montana, there are scattered records east of the Continental Divide across the south-central and southeastern counties north to the Missouri River.

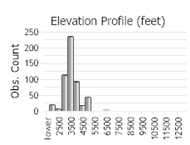

Maximum elevation: 1,999 m (6,560 ft) in Gallatin County (Rawson and Pils 2005).

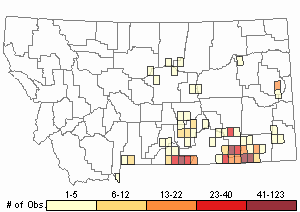

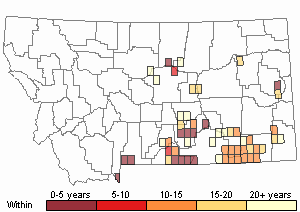

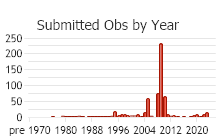

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 701

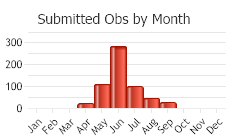

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

No information is currently available regarding Common Sagebrush Lizard migration patterns in Montana.

Information gathered outside the state indicates that Common Sagebrush Lizards probably move moderate distances of a few hundred meters, but dispersal distances are not well documented (Hammerson 1999). Home ranges may be relatively small, averaging 400-600 square meters (1,312-1,967 square feet) in Utah (Burkholder and Tanner 1974).

Habitat

In many parts of their range, the Common Sagebrush Lizard is an animal of shrub-steppe habitats, preferring rocky outcrops or sandy soils in sagebrush (

Artemisia sp.) and Antelope Bitterbrush (

Purshia tridentata) communities, and also occupying Manzanita (

Arctostaphylos sp.), Mountain Mahogany (

Cercocarpus sp.), and

Ceanothus brushland, Pinyon-Juniper woodland, and open Ponderosa Pine (

Pinus ponderosa) and Douglas-fir (

Pseudotsuga menziesii) forests (Kerfoot 1968, Marcellini and Mackey 1970, Tinkle 1973, Tinkle et al. 1993, Green et al. 2001).

In Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming it is found at higher elevations in geothermal areas on rhyolite-covered hillsides with Common Juniper (

Juniperus communis) and Lodgepole Pine (

Pinus contorta), and with woody debris scattered on the ground (Mueller 1967, Algard 1968, Koch and Peterson 1995). Favored areas tend to have a high percentage of open bare ground and a component of low to tall bushes, such as sagebrush and rabbitbrush (Stebbins 1985, Green et al. 2001). Although a ground dweller, this lizard will perch up to 1-2 m (3.3-6.6 ft) above ground in low shrubs and trees (Adolph 1990b, Hammerson 1999). Rodent burrows, shrubs, logs, and leaf litter are used for cover when disturbed (Nussbaum et al. 1983). Clutches are laid in loose soil in shallow cavities, often at the base of a shrub (Nussbaum et al. 1983, Hammerson 1999, Werner et al. 2004).

Habitat use in Montana has not been the subject of detailed studies. However, occupied habitats appear similar to other parts of the range (Paul Hendricks personal observation). This species occurs in sage-steppe habitats, sometimes in the presence of sedimentary rock outcrops (limestone and sandstone), and in areas with open stands of Limber Pine (

Pinus flexilis) and Utah juniper (

Juniperus osteosperma) or Ponderosa Pine (Hendricks and Reichel 1996b, Hendricks and Hendricks 2002, Vitt et al. 2005). In many places, open bare ground is abundant, grass cover is less than 10%, and height of shrub cover may be as low as 0.25 m (0.82 ft).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Forest and Woodland

Deciduous Forest and Woodland

Low Elevation - Xeric Forest and Woodland

Montane - Subalpine Forest and Woodland

Shrubland

Arid - Saline Shrubland

Foothills - Montane Shrubland

Sagebrush Shrubland

Grassland

Lowland - Prairie Grassland

Sparse and Barren

Sparse and Barren

Wetland and Riparian

Riparian and Wetland Forest

Riparian Shrubland

Recently Disturbed or Modified

Recently Burned

Food Habits

Adults and juveniles are “sit-and-wait” predators that hunt mainly by sight. The diversity of food items indicates prey is opportunistically taken (Burkholder and Tanner 1974). Ants, beetles, moths, and termites are the most abundant of nine orders of insects in the diet. Spiders, scorpions, pseudoscorpions, ticks, and mites have also been reported as food. Adults have been known to sometimes eat hatchling lizards (Burkholder and Tanner 1974, Rose 1976a, Koch and Peterson 1995, Hammerson 1999).

Ecology

Common Sagebrush Lizards are active during the day in the warmer hours from early May through mid-September in Yellowstone National Park (Koch and Peterson 1995). They emerge in March or April and remain active into October in other parts of the range (Nussbaum et al. 1983, Hammerson 1999). Timing of spring emergence has not been determined for Montana populations, but numerous animals of all size classes have been observed in the last week of September in southern Carbon County (Hendricks 1999a).

In southern Utah and west-central California, the annual survival rate averaged 50-60% in adults, but less than 30% in juveniles and eggs (Tinkle et al. 1993). The southern Utah population appeared to be substantially limited in resources. Home range sizes averaged 400-600 square meters (1,312-1,967 square feet) in Utah (Burkholder and Tanner 1974). Areas experimentally depopulated of this species were quickly recolonized from surrounding areas (M'Closkey et al. 1997).

Use of rodent burrows for overnight refuge, escape, and winter hibernation has been documented. In southeastern Idaho, activity was determined to be unimodal with a peak at 1100 to 1500 hours (Guyer 1978). Preferred body temperature was 30.9 °C (87.6 °F) in Yellowstone National Park (Mueller 1969).

The Common Sagebrush Lizard is probably food for a wide variety of reptiles, birds, and mammals, but documented predators are surprisingly few. Predators include Striped Whipsnake (

Masticophis taeniatus), Night Snake (

Hypsiglena torguata), Desert Collared Lizard (

Crotaphytus bicinctores), Eastern Fence Lizard (

Sceloporus undulatus), and a variety of birds including American Kestrel (

Falco sparverius), Red-tailed Hawk (

Buteo jamaicensis), Loggerhead Shrike (

Lanius ludovicianus), and Ash-throated Flycatcher (

Myiarchus cinerascens) (Knowlton and Stanford 1942, Tinkle et al. 1993, Hammerson 1999). In Montana the Green-tailed Towhee (

Pipilo chlorurus) is the only predator so far reported (Hendricks and Hendricks 2002).

Reproductive Characteristics

Essentially no information is available from Montana on any aspect of the reproductive biology of this species. Juveniles 2.8 cm (1.1 in) SVL were collected in mid- to late September in southern Carbon County, indicating eggs hatched sometime in late August or early September (Hendricks 1999a, Paul Hendricks, personal observation).

Across much of the range, eggs are laid during May-July (Tinkle et al. 1993, Hammerson 1999). Most females in Colorado and Utah produce two clutches each year. Extremes in clutch size are 1 and 8 eggs, but throughout the range clutch size averages between 3 and 5 eggs (Tinkle et al. 1993). Eggs hatch in 45-75 days, beginning in early to mid-August in Colorado and Utah, mid-to late August in west-central California (Tinkle et al. 1993, Hammerson 1999).

During three summers in Yellowstone National Park, the first hatchlings were noted 10-13 August (Mueller and Moore 1969). Hatchling SVL in Colorado, Utah and California is about 2.5-2.7 cm (0.98-1.1 in) (Ferguson and Brockman 1980, Tinkle et al. 1993, Hammerson 1999), with a growth rate of about 1 mm/week (0.04 in/week).

Sexual maturity is attained in the first year in the southern portions of the range or second year in the northern extent of the range, although a significant percentage of females in Utah may not mature until their third year (Tinkle 1973, Tinkle et al. 1993, Hammerson 1999). Females in southern Utah produce their first clutch at an age of 22-24 months. In Colorado and Utah, most adult females produce 2 clutches annually. The mean annual survival rate of young and adults is quite variable, but averages about 45% in Utah (Tinkle et al. 1993). Although as many as three-fourths of hatchlings may die (Tinkle 1973, Burkholder and Tanner 1974, Hammerson 1999). Males and females in southern Utah can live for at least six years (Tinkle et al. 1993).

Management

The following was taken from the Status and Conservation section for the Common Sagebrush Lizard in

Maxell et al. 2009).

At the time the comprehensive summaries of amphibians and reptiles in Montana (Maxell et al. 2003, Werner et al. 2004) were published, there were only 73 total records from 13 counties east of the Continental Divide for Common Sagebrush Lizard. Most records are from Big Horn, Carbon, Powder River, and Rosebud Counties. Populations in Carbon and Powder River Counties appear to be robust (Vitt et al. 2005, Bryce Maxell personal observation), with many recent sightings during favorable conditions. Although size and trend estimates remain unavailable for any locality in Montana, including areas of recent surveys. Connectivity of populations is unknown; gaps of several hundred kilometers exist between documented occurrences along the Missouri River, the lower Yellowstone River, and the concentration of records in south-central Montana. At the local scale, removal experiments show recolonization from adjacent areas can rapidly occur in unaltered habitat (M’Closkey et al. 1997). Densities of this species can be as high as 200 individuals/ha (Tinkle 1973). Risk factors relevant to the viability of populations of this species are likely to include habitat loss/fragmentation, grazing, fire, road and trail development, on- and off-road vehicle use, use of pesticides and herbicides, oil and gas development, and surface mining. However, perhaps the greatest risk to maintaining viable populations of Common Sagebrush Lizard in Montana is the lack of baseline data on its distribution, status, habitat use, and basic biology (Maxell and Hokit 1999), which are needed to monitor trends and recognize dramatic declines when and where they occur. Few studies address or identify risk factors. In an Idaho study (Reynolds 1979), Common Sagebrush Lizards were more abundant in ungrazed than grazed sagebrush (

Artemisia sp.). They were also more abundant in sagebrush (regardless of grazing treatment) than sites dominated by introduced Crested Wheatgrass (

Agropyron cristatum) following sagebrush removal, possibly because there was more bare ground available in the sage habitat, which could facilitate the ability to bask and move quickly while hunting or escaping predators. The preference for areas with a significant shrub component, >40% bare ground, and <5% grass cover has also been observed in Oregon (Green et al. 2001). Green et al. (2001) also noted habitat loss in the region of their study due to proliferation of invasive plants and conversion of shrub-steppe to cropland. Hammerson (1999) suggested that rangeland “improvements” for livestock, involving sagebrush removal to promote grass communities, could result in local population declines in Colorado.

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Adolph, S.C. 1990b. Perch height selection by juvenile Sceloporus lizards: Interspecific differences and relationship to habitat use. Journal of Herpetology 24(1): 69-75.

Adolph, S.C. 1990b. Perch height selection by juvenile Sceloporus lizards: Interspecific differences and relationship to habitat use. Journal of Herpetology 24(1): 69-75. Algard, G.A. 1968. Distribution, temperature and population studies of Sceloporus graciosus graciosous in Yellowstone National Park. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 34 p.

Algard, G.A. 1968. Distribution, temperature and population studies of Sceloporus graciosus graciosous in Yellowstone National Park. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 34 p. Burkholder, G.L. and W.W. Tanner. 1974. Life history and ecology of the Great Basin sagebrush swift, Sceloporus graciosus graciosus Baird and Girard, 1852. BYU Science Bulletin Biological Series 14(5): 1-42.

Burkholder, G.L. and W.W. Tanner. 1974. Life history and ecology of the Great Basin sagebrush swift, Sceloporus graciosus graciosus Baird and Girard, 1852. BYU Science Bulletin Biological Series 14(5): 1-42. Censky, E.J. 1986. Sceloporus graciosus Baird and Girard. Sagebrush lizard. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 386:1-4.

Censky, E.J. 1986. Sceloporus graciosus Baird and Girard. Sagebrush lizard. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 386:1-4. Degenhardt, W.G. and K.L. Jones. 1972. A new sagebrush lizard, Sceloporus graciosus, from New Mexico and Texas. Herpetologica 28:212-217.

Degenhardt, W.G. and K.L. Jones. 1972. A new sagebrush lizard, Sceloporus graciosus, from New Mexico and Texas. Herpetologica 28:212-217. Ferguson, G.W. and T. Brockman. 1980. Geographic differences of growth rate of Sceloporus lizards (Sauria: Iguanidae). Copeia 1980: 259-264.

Ferguson, G.W. and T. Brockman. 1980. Geographic differences of growth rate of Sceloporus lizards (Sauria: Iguanidae). Copeia 1980: 259-264. Green, G.A., K.B. Livezey, and R.L. Morgan. 2001. Habitat selection by northern sagebrush lizards (Sceloporus graciosus graciosus) in the Columbia Basin, Oregon. Northwestern Naturalist 82:111-115.

Green, G.A., K.B. Livezey, and R.L. Morgan. 2001. Habitat selection by northern sagebrush lizards (Sceloporus graciosus graciosus) in the Columbia Basin, Oregon. Northwestern Naturalist 82:111-115. Guyer, C. 1978. Comparative ecology of the short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma douglassi) and the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporous graciosus). Unpublished Thesis, Idaho State University. 130 pp.

Guyer, C. 1978. Comparative ecology of the short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma douglassi) and the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporous graciosus). Unpublished Thesis, Idaho State University. 130 pp. Hammerson, G.A. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. University Press of Colorado & Colorado Division of Wildlife. Denver, CO. 484 p.

Hammerson, G.A. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. University Press of Colorado & Colorado Division of Wildlife. Denver, CO. 484 p. Hendricks, P. 1999a. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Bureau of Land Management Miles City District, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 80 p.

Hendricks, P. 1999a. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Bureau of Land Management Miles City District, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 80 p. Hendricks, P. and J.D. Reichel. 1996b. Preliminary amphibian and reptile survey of the Ashland District, Custer National Forest: 1995. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 79 p.

Hendricks, P. and J.D. Reichel. 1996b. Preliminary amphibian and reptile survey of the Ashland District, Custer National Forest: 1995. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 79 p. Hendricks, P. and L.N. Hendricks. 2002. Predatory attack by green-tailed towhee on sagebrush lizard. Northwestern Naturalist 83:57-59.

Hendricks, P. and L.N. Hendricks. 2002. Predatory attack by green-tailed towhee on sagebrush lizard. Northwestern Naturalist 83:57-59. Hoberg, T., and C. Gause. 1989. Reptiles & amphibians of North Dakota. North Dakota Outdoors 55(1):7-18.

Hoberg, T., and C. Gause. 1989. Reptiles & amphibians of North Dakota. North Dakota Outdoors 55(1):7-18. Kerfoot, W.C. 1968. Geographic variability of the lizard, Sceloporus graciosus Baird and Girard, in the eastern part of its range. Copeia 1968: 139-152.

Kerfoot, W.C. 1968. Geographic variability of the lizard, Sceloporus graciosus Baird and Girard, in the eastern part of its range. Copeia 1968: 139-152. Knowlton, G.F. and J.S. Stanford. 1942. Reptiles eaten by birds. Copeia 1942: 186.

Knowlton, G.F. and J.S. Stanford. 1942. Reptiles eaten by birds. Copeia 1942: 186. Koch, E.D. and C.R. Peterson. 1995. Amphibians and reptiles of Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT. 188 p.

Koch, E.D. and C.R. Peterson. 1995. Amphibians and reptiles of Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT. 188 p. Marcellini, D. and J.P. Mackey. 1970. Habitat preferences of the lizards Sceloporus occidentalis and S. graciosus (Lacertilia, Iguanidae). Herpetologica 26: 51-56.

Marcellini, D. and J.P. Mackey. 1970. Habitat preferences of the lizards Sceloporus occidentalis and S. graciosus (Lacertilia, Iguanidae). Herpetologica 26: 51-56. Maxell, B.A. and D.G. Hokit. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles. Pages 2.1– 2.30 In G. Joslin and H. Youmans, committee chairs. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a compendium of the current state of understanding in Montana. Committee on Effects of Recreation on Wildlife, Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Maxell, B.A. and D.G. Hokit. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles. Pages 2.1– 2.30 In G. Joslin and H. Youmans, committee chairs. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a compendium of the current state of understanding in Montana. Committee on Effects of Recreation on Wildlife, Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. Maxell, B.A., J.K. Werner, P. Hendricks, and D.L. Flath. 2003. Herpetology in Montana: a history, status summary, checklists, dichotomous keys, accounts for native, potentially native, and exotic species, and indexed bibliography. Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology, Northwest Fauna Number 5. Olympia, WA. 135 p.

Maxell, B.A., J.K. Werner, P. Hendricks, and D.L. Flath. 2003. Herpetology in Montana: a history, status summary, checklists, dichotomous keys, accounts for native, potentially native, and exotic species, and indexed bibliography. Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology, Northwest Fauna Number 5. Olympia, WA. 135 p. Maxell, B.A., P. Hendricks, M.T. Gates, and S. Lenard. 2009. Montana amphibian and reptile status assessment, literature review, and conservation plan, June 2009. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 643 p.

Maxell, B.A., P. Hendricks, M.T. Gates, and S. Lenard. 2009. Montana amphibian and reptile status assessment, literature review, and conservation plan, June 2009. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 643 p. M'Closkey, R.T., S.J. Hecnar, D.R. Chalcraft, J.E. Cotter, J. Johnston, and R. Poulin. 1997. Colonization and saturation of habitats by lizards. Oikos 78:283-290.

M'Closkey, R.T., S.J. Hecnar, D.R. Chalcraft, J.E. Cotter, J. Johnston, and R. Poulin. 1997. Colonization and saturation of habitats by lizards. Oikos 78:283-290. Mueller, C. F., and R. E. Moore. 1969. Growth of the sagebrush lizard, Sceloporus graciosus, in Yellowstone National Park. Herpetologica 25:35-38.

Mueller, C. F., and R. E. Moore. 1969. Growth of the sagebrush lizard, Sceloporus graciosus, in Yellowstone National Park. Herpetologica 25:35-38. Mueller, C.F. 1967. Temperature and energy characteristics of the Sagebrush Lizard in Yellowstone National Park. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 38 p.

Mueller, C.F. 1967. Temperature and energy characteristics of the Sagebrush Lizard in Yellowstone National Park. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 38 p. Mueller, C.F. 1969. Temperature and energy characteristics of the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus) in Yellowstone National Park. Copeia 1969:153-160.

Mueller, C.F. 1969. Temperature and energy characteristics of the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus) in Yellowstone National Park. Copeia 1969:153-160. Nussbaum, R.A., E.D. Brodie, Jr. and R.M. Storm. 1983. Amphibians and reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. University of Idaho Press. Moscow, ID. 332 pp.

Nussbaum, R.A., E.D. Brodie, Jr. and R.M. Storm. 1983. Amphibians and reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. University of Idaho Press. Moscow, ID. 332 pp. Rawson, Jesse M., and Andrew Pils. 2005. Range Extension for the Northern Sagebrush Lizard in Southwest Montana. Northwest Science, 79(4): 281.

Rawson, Jesse M., and Andrew Pils. 2005. Range Extension for the Northern Sagebrush Lizard in Southwest Montana. Northwest Science, 79(4): 281. Reynolds, T.D. 1979. Response of reptiles populations to different land management practices on the Idaho national engineering laboratory site. Great Basin Naturalist 39(3): 255-262.

Reynolds, T.D. 1979. Response of reptiles populations to different land management practices on the Idaho national engineering laboratory site. Great Basin Naturalist 39(3): 255-262. Rose, B.R. 1976a. Dietary overlap of Sceloporus occidentalis and S. gracious. Copeia 1976: 818-820.

Rose, B.R. 1976a. Dietary overlap of Sceloporus occidentalis and S. gracious. Copeia 1976: 818-820. St. John, A.D. 2002. Reptiles of the northwest: California to Alaska, Rockies to the coast. Lone Pine Publishing, Renton, WA. 272 p.

St. John, A.D. 2002. Reptiles of the northwest: California to Alaska, Rockies to the coast. Lone Pine Publishing, Renton, WA. 272 p. Stebbins, R.C. 1985. A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 336 pp.

Stebbins, R.C. 1985. A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 336 pp. Tinkle, D.W. 1973. A population analysis of the sagebrush lizard, Sceloporus graciosus, in southern Utah. Copeia 1973: 284-296.

Tinkle, D.W. 1973. A population analysis of the sagebrush lizard, Sceloporus graciosus, in southern Utah. Copeia 1973: 284-296. Tinkle, D.W., A.E. Dunham, and J.D. Congdon. 1993. Life history and demographic variation in the lizard Sceloporus graciosus: a long-term study. Ecology 74(8): 2413-2429.

Tinkle, D.W., A.E. Dunham, and J.D. Congdon. 1993. Life history and demographic variation in the lizard Sceloporus graciosus: a long-term study. Ecology 74(8): 2413-2429. Vitt, L.J., J.P. Caldwell, and D.B. Shepard. 2005. Inventory of amphibians and reptiles in the Billings Field Office Region, Montana. Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History and Department of Zoology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK. 33 pp.

Vitt, L.J., J.P. Caldwell, and D.B. Shepard. 2005. Inventory of amphibians and reptiles in the Billings Field Office Region, Montana. Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History and Department of Zoology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK. 33 pp. Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks and D.L. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and Reptiles of Montana. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, MT. 262 pp.

Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks and D.L. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and Reptiles of Montana. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, MT. 262 pp.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? [OEA] Olson Elliot and Associates Research. 1985. 1983-1984 Wildlife monitoring report for the CX Ranch project. Olson Elliot and Associates Research. Helena, MT.

[OEA] Olson Elliot and Associates Research. 1985. 1983-1984 Wildlife monitoring report for the CX Ranch project. Olson Elliot and Associates Research. Helena, MT. [PRESI] Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. 1998a. Big Sky Mine 1997 wildlife monitoring studies. Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. Gillete, WY.

[PRESI] Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. 1998a. Big Sky Mine 1997 wildlife monitoring studies. Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. Gillete, WY. [PRESI] Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. 1998b. Spring Creek Mine 1997 wildlife monitoring studies. Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. Gillete, WY.

[PRESI] Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. 1998b. Spring Creek Mine 1997 wildlife monitoring studies. Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. Gillete, WY. [USFWS] US Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; animal candidate review for listing as endangered or threatened species. Federal Register 59(219): 58982-59028.

[USFWS] US Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; animal candidate review for listing as endangered or threatened species. Federal Register 59(219): 58982-59028. [VTNWI] VTN Wyoming Incorporated. No Date. Second year's analysis of terrestrial wildlife on proposed mine access and railroad routes in southern Montana and northern Wyoming, March 1979 - February 1980. VTN Wyoming Incorporated. Sheridan, WY. 62 p.

[VTNWI] VTN Wyoming Incorporated. No Date. Second year's analysis of terrestrial wildlife on proposed mine access and railroad routes in southern Montana and northern Wyoming, March 1979 - February 1980. VTN Wyoming Incorporated. Sheridan, WY. 62 p. Adolph, S.C. 1987. Physiological and behavioral ecology of the lizards Sceloporus occidentalis and Sceloporus graciosus. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Washington. Seattle. 121pp.

Adolph, S.C. 1987. Physiological and behavioral ecology of the lizards Sceloporus occidentalis and Sceloporus graciosus. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Washington. Seattle. 121pp. Adolph, S.C. 1990a. Influence of behavioral thermoregulation on microhabitat use by two Sceloporus lizards. Ecology 71(1): 315-327.

Adolph, S.C. 1990a. Influence of behavioral thermoregulation on microhabitat use by two Sceloporus lizards. Ecology 71(1): 315-327. Albers, Mark., 1995, Draft Biological Assessment: Tongue River Basin Project. May 1995. In Tongue River Basin Project Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Appendix B. June 1995.

Albers, Mark., 1995, Draft Biological Assessment: Tongue River Basin Project. May 1995. In Tongue River Basin Project Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Appendix B. June 1995. Allen, J. A. 1874. Notes on the natural history of portions of Dakota and Montana Territories, being the substance of a report to the Secretary of War on the collections made by the North Pacific Railroad Expedition of 1873. Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History. pp. 68-70.

Allen, J. A. 1874. Notes on the natural history of portions of Dakota and Montana Territories, being the substance of a report to the Secretary of War on the collections made by the North Pacific Railroad Expedition of 1873. Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History. pp. 68-70. Baxter, G.T. and M.D. Stone. 1985. Amphibians and reptiles of Wyoming. Second edition. Wyoming Game and Fish Department. Cheyenne, WY. 137 p.

Baxter, G.T. and M.D. Stone. 1985. Amphibians and reptiles of Wyoming. Second edition. Wyoming Game and Fish Department. Cheyenne, WY. 137 p. Beal, M.D. 1951. The occurrence and seasonal activity of vertebrates in the Norris and Gibbon Geyser Basins of Yellowstone National Park. M.S. Thesis. Utah State Agricultural College. Logan, Utah. 61 pp.

Beal, M.D. 1951. The occurrence and seasonal activity of vertebrates in the Norris and Gibbon Geyser Basins of Yellowstone National Park. M.S. Thesis. Utah State Agricultural College. Logan, Utah. 61 pp. Bergeron, D. 1978. Terrestrial Wildlife Survey Coal creek Mine Area, Montana. Unpublished report for Coal Creek Mining Co., Ashland, Montana.

Bergeron, D. 1978. Terrestrial Wildlife Survey Coal creek Mine Area, Montana. Unpublished report for Coal Creek Mining Co., Ashland, Montana. Bergeron, D.J. 1978a. Terrestrial wildlife survey Divide Mine area, Montana 1977-1978. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT.

Bergeron, D.J. 1978a. Terrestrial wildlife survey Divide Mine area, Montana 1977-1978. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT. Bergeron, D.J. 1978b. Terrestrial wildlife survey P-M Mine area, Montana 1977-1978. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT.

Bergeron, D.J. 1978b. Terrestrial wildlife survey P-M Mine area, Montana 1977-1978. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT. Brunson, R.B. 1955. Check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 15: 27-29.

Brunson, R.B. 1955. Check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 15: 27-29. Bureau of Indian Affairs, Department of the Interior. 1981. Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Unpublished report for the Crow/Shell Coal Lease, Crow Indian Reservation, Montana.

Bureau of Indian Affairs, Department of the Interior. 1981. Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Unpublished report for the Crow/Shell Coal Lease, Crow Indian Reservation, Montana. Butts, T.W. 1997. Mountain Inc. wildlife monitoring Bull Mountains Mine No. 1, 1996. Western Technology and Engineering. Helena, MT.

Butts, T.W. 1997. Mountain Inc. wildlife monitoring Bull Mountains Mine No. 1, 1996. Western Technology and Engineering. Helena, MT. Carlson, J. (Coordinator, Montana Animal Species of Concern Committee). 2003. Montana Animal Species of Concern January 2003. Helena, MT: Montana Natural Heritage Program and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. In Press. 12p.

Carlson, J. (Coordinator, Montana Animal Species of Concern Committee). 2003. Montana Animal Species of Concern January 2003. Helena, MT: Montana Natural Heritage Program and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. In Press. 12p. Carpenter, C.C. 1978. Comparative display behavior in the genus Sceloporus (Iguanidae). Milwaukee Public Museum Contributions to Biology and Geology 18: 1-71.

Carpenter, C.C. 1978. Comparative display behavior in the genus Sceloporus (Iguanidae). Milwaukee Public Museum Contributions to Biology and Geology 18: 1-71. Censky, E.J. 1986. Sceloporus graciosus. Catalog of American Amphibians and Reptiles. 386.1-4.

Censky, E.J. 1986. Sceloporus graciosus. Catalog of American Amphibians and Reptiles. 386.1-4. Collins, J.T. 1991. A new taxonomic arrangement for some North American amphibians and reptiles. Herpetological Review 22:42-43.

Collins, J.T. 1991. A new taxonomic arrangement for some North American amphibians and reptiles. Herpetological Review 22:42-43. Collins, J.T. 1997. Standard common and current scientific names for North American amphibians and reptiles. Fourth edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Herpetological Circular No. 25. 40 pp.

Collins, J.T. 1997. Standard common and current scientific names for North American amphibians and reptiles. Fourth edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Herpetological Circular No. 25. 40 pp. Congdon, J.D. and D.W. Tinkle. 1982a. Energy expenditure in free-ranging sagebrush lizards (Sceloporus graciosus). Canadian Journal of Zoology 60: 1412-1416.

Congdon, J.D. and D.W. Tinkle. 1982a. Energy expenditure in free-ranging sagebrush lizards (Sceloporus graciosus). Canadian Journal of Zoology 60: 1412-1416. Cooper, J. G. 1869. Notes on the fauna of the Upper Missouri. American Naturalist 3(6):294-299.

Cooper, J. G. 1869. Notes on the fauna of the Upper Missouri. American Naturalist 3(6):294-299. Cope, E.D. 1872. Report on the recent reptiles and fishes of the survey, collected by Campbell Carrington and C.M. Dawes. pp. 467-469 In: F.V. Hayden, Preliminary report of the United States geological survey of Montana and portions of adjacent territories; being a fifth annual report of progress. 538 pp. 42nd Congress, 2nd Session, House Executive Document Number 326. Serial 1520.

Cope, E.D. 1872. Report on the recent reptiles and fishes of the survey, collected by Campbell Carrington and C.M. Dawes. pp. 467-469 In: F.V. Hayden, Preliminary report of the United States geological survey of Montana and portions of adjacent territories; being a fifth annual report of progress. 538 pp. 42nd Congress, 2nd Session, House Executive Document Number 326. Serial 1520. Cope, E.D. 1900. The crocodilians, lizards, and snakes of North America. Report of the U.S. National Museum 1898: 153-1270.

Cope, E.D. 1900. The crocodilians, lizards, and snakes of North America. Report of the U.S. National Museum 1898: 153-1270. Crother, B.I. (ed.) 2008. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico. SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 37:1-84.

Crother, B.I. (ed.) 2008. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico. SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 37:1-84. Cuellar, O. 1993. Lizard population ecology: a long term community study. Bulletin D’Ecologie 24(2-4): 109-149.

Cuellar, O. 1993. Lizard population ecology: a long term community study. Bulletin D’Ecologie 24(2-4): 109-149. Day, D. 1989. Montco Terrestrial Wildlife Monitoring Report. Unpublished report for Montco, Billings, Montana.

Day, D. 1989. Montco Terrestrial Wildlife Monitoring Report. Unpublished report for Montco, Billings, Montana. Day, D., P.J. Farmer, and C.E. Farmer. 1989. Montco terrestrial wildlife monitoring report December, 1987 - July, 1989. Montco, Billings, MT, and Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT.

Day, D., P.J. Farmer, and C.E. Farmer. 1989. Montco terrestrial wildlife monitoring report December, 1987 - July, 1989. Montco, Billings, MT, and Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT. Degenhardt, W. G., C. W. Painter, and A. H. Price. 1996. Amphibians and reptiles of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Degenhardt, W. G., C. W. Painter, and A. H. Price. 1996. Amphibians and reptiles of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. Deslippe, R.J. and R.T. M'Closkey. 1991. An experimental test of mate defense in an iguanid lizard (Sceloporus graciosus). Ecology 72(4): 1218-1224.

Deslippe, R.J. and R.T. M'Closkey. 1991. An experimental test of mate defense in an iguanid lizard (Sceloporus graciosus). Ecology 72(4): 1218-1224. Dood, A.R. 1980. Terry Badlands nongame survey and inventory final report. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks and Bureau of Land Management, Helena, MT. 70 pp.

Dood, A.R. 1980. Terry Badlands nongame survey and inventory final report. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks and Bureau of Land Management, Helena, MT. 70 pp. ECON, Inc. (Ecological Consulting Service), Helena, MT., 1976, Colstrip 10 x 20 Area wildlife and wildlife habitat annual monitoring report, 1976. Proj. 135-85-A. December 31, 1976.

ECON, Inc. (Ecological Consulting Service), Helena, MT., 1976, Colstrip 10 x 20 Area wildlife and wildlife habitat annual monitoring report, 1976. Proj. 135-85-A. December 31, 1976. ECON, Inc. (Ecological Consulting Service), Helena, MT., 1979, Annual wildllife report of the Colstrip Area for 1978. Proj. 195-85-A. April 6, 1979.

ECON, Inc. (Ecological Consulting Service), Helena, MT., 1979, Annual wildllife report of the Colstrip Area for 1978. Proj. 195-85-A. April 6, 1979. ECON, Inc. (Ecological Consulting Service), Helena, MT., 1979, Annual wildllife report of the Colstrip Area for 1979, including a special raptor research study. Proj. 216-85-A. March 1, 1980.

ECON, Inc. (Ecological Consulting Service), Helena, MT., 1979, Annual wildllife report of the Colstrip Area for 1979, including a special raptor research study. Proj. 216-85-A. March 1, 1980. Econ, Inc. 1988. Wildlife monitoring report, 1987 field season, Big Sky Mine. March 1988. In Peabody Mining and Reclamation Plan Big Sky Mine Area B. Vol. 8, cont., Tab 10 - Wildlife Resources. Appendix 10-1, 1987 Annual Wildlife Report.

Econ, Inc. 1988. Wildlife monitoring report, 1987 field season, Big Sky Mine. March 1988. In Peabody Mining and Reclamation Plan Big Sky Mine Area B. Vol. 8, cont., Tab 10 - Wildlife Resources. Appendix 10-1, 1987 Annual Wildlife Report. Econ, Inc., Helena, MT., 1978, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife and wildlife habitat monitoring study. Proj. 190-85-A. December 31, 1978.

Econ, Inc., Helena, MT., 1978, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife and wildlife habitat monitoring study. Proj. 190-85-A. December 31, 1978. Etheridge, R. 1964. The skeletal morphology and systematic relationships of sceloporine lizards. Copeia 1964(4): 610-631.

Etheridge, R. 1964. The skeletal morphology and systematic relationships of sceloporine lizards. Copeia 1964(4): 610-631. Farmer, P. 1980. Terrestrial wildlife monitoring study, Pearl area, Montana June, 1978 - May, 1980. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT.

Farmer, P. 1980. Terrestrial wildlife monitoring study, Pearl area, Montana June, 1978 - May, 1980. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT. Farmer, P. J. 1980. Terrestrial Wildlife Monitoring Study, Pearl Area, Montana, June, 1978 - May, 1980. Tech. Rep. by WESTECH for Shell Oil Co.

Farmer, P. J. 1980. Terrestrial Wildlife Monitoring Study, Pearl Area, Montana, June, 1978 - May, 1980. Tech. Rep. by WESTECH for Shell Oil Co. Ferguson, G.W. 1971. Observations on the behavior and interactions of two sympatric Sceloporus in Utah. American Midland Naturalist 86: 190-196.

Ferguson, G.W. 1971. Observations on the behavior and interactions of two sympatric Sceloporus in Utah. American Midland Naturalist 86: 190-196. Fjell, Alan K., 1986, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1985 field season. March 1986.

Fjell, Alan K., 1986, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1985 field season. March 1986. Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan, compilers., 1984, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1983 field season. February 1984.

Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan, compilers., 1984, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1983 field season. February 1984. Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan., 1983, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1982 field season. May 1983.

Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan., 1983, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1982 field season. May 1983. Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan., 1985, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1984 field season. February 1985.

Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan., 1985, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1984 field season. February 1985. Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan., 1987, Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1986 field season. April 1987.

Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan., 1987, Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1986 field season. April 1987. Gates, M.T. 2005. Amphibian and reptile baseline survey: CX field study area Bighorn County, Montana. Report to Billings and Miles City Field Offices of Bureau of Land Management. Maxim Technologies, Billings, MT. 28pp + Appendices.

Gates, M.T. 2005. Amphibian and reptile baseline survey: CX field study area Bighorn County, Montana. Report to Billings and Miles City Field Offices of Bureau of Land Management. Maxim Technologies, Billings, MT. 28pp + Appendices. Germaine, S.S. and H.L. Germaine. 2003. Lizard distributions and reproductive success in a ponderosa pine forest. Journal of Herpetology 37(4):645-652.

Germaine, S.S. and H.L. Germaine. 2003. Lizard distributions and reproductive success in a ponderosa pine forest. Journal of Herpetology 37(4):645-652. Goldberg, S.R. and C.R. Bursey. 1989. Physaloptera retusa (Nematoda, Physalopteridae) in naturally infected sagebrush lizards, Sceloporus graciosus (Iguanidae). Journal of Wildlife Diseases 25(3): 425-429.

Goldberg, S.R. and C.R. Bursey. 1989. Physaloptera retusa (Nematoda, Physalopteridae) in naturally infected sagebrush lizards, Sceloporus graciosus (Iguanidae). Journal of Wildlife Diseases 25(3): 425-429. Goldberg, S.R. and C.R. Bursey. 1991a. Duration of attachment by mites and ticks on the iguanid lizards Sceloporus graciosus and Uta stansburiana. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 27(4): 719-722.

Goldberg, S.R. and C.R. Bursey. 1991a. Duration of attachment by mites and ticks on the iguanid lizards Sceloporus graciosus and Uta stansburiana. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 27(4): 719-722. Goldberg, S.R., C.R. Bursey, and C.T. McAllister. 1995. Gastrointestinal helminths of nine species of Sceloporus lizards (Phrynosomatidae) from Texas. Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 62(2):188-196.

Goldberg, S.R., C.R. Bursey, and C.T. McAllister. 1995. Gastrointestinal helminths of nine species of Sceloporus lizards (Phrynosomatidae) from Texas. Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 62(2):188-196. Goldberg, S.R., C.R. Bursey, and R. Tawil. 1994. Gastrointestinal helminths of Sceloporus lizards (Phrynosomatidae) from Arizona. Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 61(1): 73-83.

Goldberg, S.R., C.R. Bursey, and R. Tawil. 1994. Gastrointestinal helminths of Sceloporus lizards (Phrynosomatidae) from Arizona. Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 61(1): 73-83. Guyer, C. 1991. Orientation and homing behavior as a measure of affinity for the home range in two species of Iguanid lizards. Amphibia-Reptilia 12(4): 373-384.

Guyer, C. 1991. Orientation and homing behavior as a measure of affinity for the home range in two species of Iguanid lizards. Amphibia-Reptilia 12(4): 373-384. Guyer, C. and A.D. Linder. 1985a. Growth and population structure of the short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma douglassi) and the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus) in southeastern Idaho. Northwest Science 59(4): 294-303.

Guyer, C. and A.D. Linder. 1985a. Growth and population structure of the short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma douglassi) and the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus) in southeastern Idaho. Northwest Science 59(4): 294-303. Guyer, C. and A.D. Linder. 1985b. Thermal ecology and activity patterns of the short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma douglassi) and the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus) in southeastern Idaho (USA). Great Basin Naturalist 45(4): 607-614.

Guyer, C. and A.D. Linder. 1985b. Thermal ecology and activity patterns of the short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma douglassi) and the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus) in southeastern Idaho (USA). Great Basin Naturalist 45(4): 607-614. Hanauska-Brown, L., B.A. Maxell, A. Petersen, and S. Story. 2014. Diversity Monitoring in Montana 2008-2010 Final Report. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Helena, MT. 78 pp.

Hanauska-Brown, L., B.A. Maxell, A. Petersen, and S. Story. 2014. Diversity Monitoring in Montana 2008-2010 Final Report. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Helena, MT. 78 pp. Horstman, G. 1995. Sceloporus graciosus graciosus (northern sagebrush lizard). Herpetological Review 26(1): 45.

Horstman, G. 1995. Sceloporus graciosus graciosus (northern sagebrush lizard). Herpetological Review 26(1): 45. Humphris, Michael., 1993, Wildlife Monitoring Report. Spring Creek Coal Company 1993 Mining Annual Report. Appendix I. April 11, 1993.

Humphris, Michael., 1993, Wildlife Monitoring Report. Spring Creek Coal Company 1993 Mining Annual Report. Appendix I. April 11, 1993. Humphris, Michael., 1994, Wildlife Monitoring Report. Spring Creek Coal Company 1994 Mining Annual Report. Appendix I. April 1994.

Humphris, Michael., 1994, Wildlife Monitoring Report. Spring Creek Coal Company 1994 Mining Annual Report. Appendix I. April 1994. James, S.E. and R.T. M'Closkey. 2002. Patterns of microhabitat use in a sympatric lizard assemblage. Canadian Journal of Zoology 80(12):2226-2234.

James, S.E. and R.T. M'Closkey. 2002. Patterns of microhabitat use in a sympatric lizard assemblage. Canadian Journal of Zoology 80(12):2226-2234. James, S.E. and R.T. M'Closkey. 2003. Lizard microhabitat and fire fuel management. Biological Conservation 114(2):293-297.

James, S.E. and R.T. M'Closkey. 2003. Lizard microhabitat and fire fuel management. Biological Conservation 114(2):293-297. Jameson, E.W., Jr. 1974. Fat and breeding cycles in a montane population of Sceloporus graciosus. Journal of Herpetology 8(4): 311-322.

Jameson, E.W., Jr. 1974. Fat and breeding cycles in a montane population of Sceloporus graciosus. Journal of Herpetology 8(4): 311-322. Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. Knowlton, G.F. 1953. Some insect food of Sceloporus g. graciosus. Herpetologica 9: 70.

Knowlton, G.F. 1953. Some insect food of Sceloporus g. graciosus. Herpetologica 9: 70. Knox, S.C., C. Chambers, and S.S. Germaine. 2001. Habitat associations of the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus): potential responsess of an ectotherm to ponderosa pine forest rehabilitation. USFS Rocky Mountain Research Station Preoceedings RMRS-P 22:95-98.

Knox, S.C., C. Chambers, and S.S. Germaine. 2001. Habitat associations of the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus): potential responsess of an ectotherm to ponderosa pine forest rehabilitation. USFS Rocky Mountain Research Station Preoceedings RMRS-P 22:95-98. Koch, E.D. and C.R. Peterson. 1989. A preliminary survey of the distribution of amphibians and reptiles in Yellowstone National Park. pp. 47-49. In: Rare, sensitive and threatened species of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, T.W. Clark, A.H. Harvey, R.D. Dorn, D.C. Genter, and C. Groves (eds.), Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative , Montana Natural Heritage Program, The Nature Conservancy, and Mountain West Environmental Services. 153 p.

Koch, E.D. and C.R. Peterson. 1989. A preliminary survey of the distribution of amphibians and reptiles in Yellowstone National Park. pp. 47-49. In: Rare, sensitive and threatened species of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, T.W. Clark, A.H. Harvey, R.D. Dorn, D.C. Genter, and C. Groves (eds.), Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative , Montana Natural Heritage Program, The Nature Conservancy, and Mountain West Environmental Services. 153 p. Lemos-Espinal, J.A., G.R. Smith, and R.E. Ballinger. 1996. Covariation of egg size, clutch size, and offspring survivorship in the genus Sceloporus. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 32(2): 58-66.

Lemos-Espinal, J.A., G.R. Smith, and R.E. Ballinger. 1996. Covariation of egg size, clutch size, and offspring survivorship in the genus Sceloporus. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 32(2): 58-66. Lynch, J.D. 1985. Annotated checklist of the amphibians and reptiles of Nebraska. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences 13: 33-57.

Lynch, J.D. 1985. Annotated checklist of the amphibians and reptiles of Nebraska. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences 13: 33-57. Martin, P.R. 1980a. Terrestrial wildlife habitat inventory in southeastern Montana. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks and Bureau of Land Management, Helena MT. 114 p.

Martin, P.R. 1980a. Terrestrial wildlife habitat inventory in southeastern Montana. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks and Bureau of Land Management, Helena MT. 114 p. Martin, P.R. 1980b. Terrestrial wildlife inventory in selected coal areas of Montana. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks and Bureau of Land Management, Helena, MT. 84 p.

Martin, P.R. 1980b. Terrestrial wildlife inventory in selected coal areas of Montana. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks and Bureau of Land Management, Helena, MT. 84 p. Martin, P.R., K. Dubois and H.B. Youmans. 1981. Terrestrial wildlife inventory in selected coal areas, Powder River resources area final report. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks and Bureau of Land Management, Helena, MT. No. YA-553-CTO- 24. 288 p.

Martin, P.R., K. Dubois and H.B. Youmans. 1981. Terrestrial wildlife inventory in selected coal areas, Powder River resources area final report. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks and Bureau of Land Management, Helena, MT. No. YA-553-CTO- 24. 288 p. Martins, E.P. 1991. Individual and sex differences in the use of the push-up display by the sagebrush lizard, Sceloporus graciosus. Animal Behaviour 41(3): 403-416.

Martins, E.P. 1991. Individual and sex differences in the use of the push-up display by the sagebrush lizard, Sceloporus graciosus. Animal Behaviour 41(3): 403-416. Martins, E.P. 1993a. A comparative study of the evolution of Sceloporus pushup displays. American Naturalist 142: 994-1018.

Martins, E.P. 1993a. A comparative study of the evolution of Sceloporus pushup displays. American Naturalist 142: 994-1018. Martins, E.P. 1993b. Contextual use of the push-up display by the sagebrush lizard, Sceloporus graciosus. Animal Behaviour 45(1): 25-36.

Martins, E.P. 1993b. Contextual use of the push-up display by the sagebrush lizard, Sceloporus graciosus. Animal Behaviour 45(1): 25-36. Martins, E.P. 1994. Structural complexity in a lizard communication system: the Sceloporus graciosus "push-up" display. Copeia 1994(4): 944-955.

Martins, E.P. 1994. Structural complexity in a lizard communication system: the Sceloporus graciosus "push-up" display. Copeia 1994(4): 944-955. Martins, E.P., A.N. Bissell, and K.K. Morgan. 1998. Population diffferences in a lizard communicative display: evidence for rapid change in structure and function. Animal Behaviour 56(5):1113-1119.

Martins, E.P., A.N. Bissell, and K.K. Morgan. 1998. Population diffferences in a lizard communicative display: evidence for rapid change in structure and function. Animal Behaviour 56(5):1113-1119. Martins, E.P., T.J. Ord, and S.W. Davenport. 2005. Combining motions into complex displays: playbacks with a robotic lizard. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 58(4):351-360.

Martins, E.P., T.J. Ord, and S.W. Davenport. 2005. Combining motions into complex displays: playbacks with a robotic lizard. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 58(4):351-360. Maxim Technologies, Inc., 2002, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: 2002 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 2001 - November 30, 2002. Febr. 24, 2002.

Maxim Technologies, Inc., 2002, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: 2002 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 2001 - November 30, 2002. Febr. 24, 2002. M'Closkey, R.T., S.J. Hecnar, D.R. Chalcraft, and J.E. Cotter. 1998. Size distributions and sex ratios of colonizing lizards. Oecologica (Berlin) 116(4):501-509.

M'Closkey, R.T., S.J. Hecnar, D.R. Chalcraft, and J.E. Cotter. 1998. Size distributions and sex ratios of colonizing lizards. Oecologica (Berlin) 116(4):501-509. Morrison, M.L. and L.S. Hall. 1999. Habitat characteristics of reptiles in pinyon-juniper woodland. Great Basin Naturalist 59(3):288-291.

Morrison, M.L. and L.S. Hall. 1999. Habitat characteristics of reptiles in pinyon-juniper woodland. Great Basin Naturalist 59(3):288-291. Morrison, R.L. and L. Powell. 1988. New distributional records of lizards in Wyoming (USA). Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences 16(0): 85-86.

Morrison, R.L. and L. Powell. 1988. New distributional records of lizards in Wyoming (USA). Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences 16(0): 85-86. Morrison, R.L. and S.K. Frost-Mason. 1991. Ultrastructural analysis of iridophore organellogenesis in a lizard, Sceloporus graciosus (Reptilia: Phrynosomatidae). Journal Of Morphology 209(2): 229-239.

Morrison, R.L. and S.K. Frost-Mason. 1991. Ultrastructural analysis of iridophore organellogenesis in a lizard, Sceloporus graciosus (Reptilia: Phrynosomatidae). Journal Of Morphology 209(2): 229-239. Mueller, C.F. 1970a. Temperature acclimation in two species of Sceloporus. Herpetologica 26(1): 83-85.

Mueller, C.F. 1970a. Temperature acclimation in two species of Sceloporus. Herpetologica 26(1): 83-85. Mueller, C.F. 1970b. Energy utilization in the lizards Sceloporus graciosus and Sceloporus occidentalis. Journal of Herpetology 4(3-4): 131-134.

Mueller, C.F. 1970b. Energy utilization in the lizards Sceloporus graciosus and Sceloporus occidentalis. Journal of Herpetology 4(3-4): 131-134. OEA Research. 1985. Wildlife Inventory:Monitoring Report for the CX Ranch Project. 1983-1984. Unpublished report for Consolidation Coal Company, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

OEA Research. 1985. Wildlife Inventory:Monitoring Report for the CX Ranch Project. 1983-1984. Unpublished report for Consolidation Coal Company, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Oechsli, L.M. 2000. Ex-urban development in the Rocky Mountain West: consequences for native vegetation, wildlife diversity, and land-use planning in Big Sky, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 73 p.

Oechsli, L.M. 2000. Ex-urban development in the Rocky Mountain West: consequences for native vegetation, wildlife diversity, and land-use planning in Big Sky, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 73 p. Patla, D.A. 1998a. Amphibians and reptiles in the Old Faithful sewage treatment area. Report to Yellowstone Center for Resources, Yellowstone National Park. 10 September, 1998. Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem Amphibian Survey and Monitoring Program, Herpetology Laboratory, Department of Biological Sciences, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID. 7 p.

Patla, D.A. 1998a. Amphibians and reptiles in the Old Faithful sewage treatment area. Report to Yellowstone Center for Resources, Yellowstone National Park. 10 September, 1998. Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem Amphibian Survey and Monitoring Program, Herpetology Laboratory, Department of Biological Sciences, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID. 7 p. Patla, D.A. and C.R. Peterson. 1996a. Amphibians and reptiles along the Grand Loop Highway in Yellowstone National Park: Tower Junction to Canyon Village. 24 February, 1996. Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem Amphibian Survey and Monitoring Program, Herpetology Laboratory, Department of Biological Sciences, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID. 49 p.

Patla, D.A. and C.R. Peterson. 1996a. Amphibians and reptiles along the Grand Loop Highway in Yellowstone National Park: Tower Junction to Canyon Village. 24 February, 1996. Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem Amphibian Survey and Monitoring Program, Herpetology Laboratory, Department of Biological Sciences, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID. 49 p. Peterson, C.R. and J.P. Shive. 2002. Herpetological survey of southcentral Idaho. Idaho Bureau of Land Management Technical Bulletin 02-3:1-97.

Peterson, C.R. and J.P. Shive. 2002. Herpetological survey of southcentral Idaho. Idaho Bureau of Land Management Technical Bulletin 02-3:1-97. Peterson, C.R., C.J. Askey, and D.A. Patla. 1993. Amphibians and reptiles along the Grand Loop and Fountain Freight Roads between Madison Junction and Biscuit Basin in Yellowstone National Park. 26 July, 1993. Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem Amphibian Survey and Monitoring Program, Herpetology Laboratory, Department of Biological Sciences, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID. 45 p.

Peterson, C.R., C.J. Askey, and D.A. Patla. 1993. Amphibians and reptiles along the Grand Loop and Fountain Freight Roads between Madison Junction and Biscuit Basin in Yellowstone National Park. 26 July, 1993. Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem Amphibian Survey and Monitoring Program, Herpetology Laboratory, Department of Biological Sciences, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID. 45 p. Pilliod, D.S. and T.C. Esque. 2023. Amphibians and reptiles. pp. 861-895. In: L.B. McNew, D.K. Dahlgren, and J.L. Beck (eds). Rangeland wildlife ecology and conservation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. 1023 p.

Pilliod, D.S. and T.C. Esque. 2023. Amphibians and reptiles. pp. 861-895. In: L.B. McNew, D.K. Dahlgren, and J.L. Beck (eds). Rangeland wildlife ecology and conservation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. 1023 p. Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 1995, Big Sky Mine 1994 wildlife monitoring studies. March 1995

Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 1995, Big Sky Mine 1994 wildlife monitoring studies. March 1995 Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 1996, Spring Creek Mine 1995 Wildlife Monitoring Studies. Spring Creek Coal Company 1995-1996 Mining Annual Report. Vol. I, App. I. May 1996.

Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 1996, Spring Creek Mine 1995 Wildlife Monitoring Studies. Spring Creek Coal Company 1995-1996 Mining Annual Report. Vol. I, App. I. May 1996. Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 1997, Spring Creek Mine 1996 Wildlife Monitoring Studies. February 1997.

Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 1997, Spring Creek Mine 1996 Wildlife Monitoring Studies. February 1997. Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 1999, 1998 wildlife monitoring: Big Sky Mine. March 1999.

Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 1999, 1998 wildlife monitoring: Big Sky Mine. March 1999. Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 1999, Spring Creek Mine 1998 Wildlife Monitoring. March 1999.

Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 1999, Spring Creek Mine 1998 Wildlife Monitoring. March 1999. Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 2000, Spring Creek Mine 1999 Wildlife Monitoring. March 2000.

Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 2000, Spring Creek Mine 1999 Wildlife Monitoring. March 2000. Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 2000, Spring Creek Mine 2000 Wildlife Monitoring. March 2000.

Powder River Eagle Studies, Inc., Gillette, WY., 2000, Spring Creek Mine 2000 Wildlife Monitoring. March 2000. Punzo, F. 1982. Clutch and egg size in several species of lizards from the desert southwest. Journal of Herpetology 16(4):414-417.

Punzo, F. 1982. Clutch and egg size in several species of lizards from the desert southwest. Journal of Herpetology 16(4):414-417. Rauscher, R.L. 1998. Amphibian and reptile survey on selected Montana Bureau of Reclamation impoundments. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Nongame Program. Bozeman, MT. 24 pp.

Rauscher, R.L. 1998. Amphibian and reptile survey on selected Montana Bureau of Reclamation impoundments. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Nongame Program. Bozeman, MT. 24 pp. Reed, K.M., P.D. Sudman, J.W. Sites, and I.F. Greenbaum. 1990. Synaptonemal complex analysis of sex chromosomes in two species of Sceloporus. Copeia 4: 1122-1129.

Reed, K.M., P.D. Sudman, J.W. Sites, and I.F. Greenbaum. 1990. Synaptonemal complex analysis of sex chromosomes in two species of Sceloporus. Copeia 4: 1122-1129. Reichel, J. and D. Flath. 1995. Identification of Montana's amphibians and reptiles. Montana Outdoors 26(3):15-34.

Reichel, J. and D. Flath. 1995. Identification of Montana's amphibians and reptiles. Montana Outdoors 26(3):15-34. Reichel, J.D. 1995b. Preliminary amphibian and reptile survey of the Sioux District of the Custer National Forest: 1994. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 75 p.

Reichel, J.D. 1995b. Preliminary amphibian and reptile survey of the Sioux District of the Custer National Forest: 1994. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 75 p. Roedel, M.D. and P. Hendricks. 1998a. Amphibian and reptile survey on the Bureau of Land Management Lewistown District: 1995-1998. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 53 p.

Roedel, M.D. and P. Hendricks. 1998a. Amphibian and reptile survey on the Bureau of Land Management Lewistown District: 1995-1998. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 53 p. Roedel, M.D. and P. Hendricks. 1998b. Amphibian and reptile inventory on the Headwaters and Dillon Resource Areas in conjunction with Red Rocks Lakes National Wildlife Refuge: 1996-1998. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 46 p.

Roedel, M.D. and P. Hendricks. 1998b. Amphibian and reptile inventory on the Headwaters and Dillon Resource Areas in conjunction with Red Rocks Lakes National Wildlife Refuge: 1996-1998. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 46 p. Rose, B.R. 1976b. Habitat and prey selection of Sceloporus occidentalis and Sceloporus graciosus. Ecology 57: 531-541.

Rose, B.R. 1976b. Habitat and prey selection of Sceloporus occidentalis and Sceloporus graciosus. Ecology 57: 531-541. Sears, M.W. 2005a. Goegraphic variation in the life history of the sagebrush lizard: the role of thermal constraints on activity. Oecologia (Berlin) 143(1):25-36.

Sears, M.W. 2005a. Goegraphic variation in the life history of the sagebrush lizard: the role of thermal constraints on activity. Oecologia (Berlin) 143(1):25-36. Sears, M.W. 2005b. Resting metabolic expenditure as a potential source of variation in growth rates of the sagebrush lizard. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A Molecular and Integrative Physiology 140(2):171-177.

Sears, M.W. 2005b. Resting metabolic expenditure as a potential source of variation in growth rates of the sagebrush lizard. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A Molecular and Integrative Physiology 140(2):171-177. Sears, M.W. and M.J. Angilletta Jr. 2003. Life-history variation in the sagebrush lizard: phenotypic plasticity or local adaptation? Ecology 84(6):1624-1634.

Sears, M.W. and M.J. Angilletta Jr. 2003. Life-history variation in the sagebrush lizard: phenotypic plasticity or local adaptation? Ecology 84(6):1624-1634. Sestrich, Clint. 2006. 2006 Hebgen Reservoir Amphibian Survey, USDA Forest Service Annual Progress Report to PPL Montana. Hebgen Lake Ranger District. Gallatin National Forest. West Yellowstone Montana.

Sestrich, Clint. 2006. 2006 Hebgen Reservoir Amphibian Survey, USDA Forest Service Annual Progress Report to PPL Montana. Hebgen Lake Ranger District. Gallatin National Forest. West Yellowstone Montana. Sinervo, B. and S.C. Adolph. 1989. Thermal sensitivity of growth rate in hatchling Sceloporus lizards: Environmental, behavioral and genetic aspects. Oecologia 78(3): 411-419.

Sinervo, B. and S.C. Adolph. 1989. Thermal sensitivity of growth rate in hatchling Sceloporus lizards: Environmental, behavioral and genetic aspects. Oecologia 78(3): 411-419. Sinervo, B. and S.C. Adolph. 1994. Growth plasticity and thermal opportunity in Sceloporus lizards. Ecology 75(3): 776-790.

Sinervo, B. and S.C. Adolph. 1994. Growth plasticity and thermal opportunity in Sceloporus lizards. Ecology 75(3): 776-790. Sites, J. W., Jr., J.W. Archie, C.J. Cole, V.O. Flores. 1992. A review of phylogenetic hypotheses for lizards of the genus (Phrynosomatidae): implications for ecological and evolutionary studies. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History (213): 1-110.

Sites, J. W., Jr., J.W. Archie, C.J. Cole, V.O. Flores. 1992. A review of phylogenetic hypotheses for lizards of the genus (Phrynosomatidae): implications for ecological and evolutionary studies. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History (213): 1-110. Sites, J.W., Jr., C.A. Porter, and P. Thompson. 1987. Genetic structure and chromosomal evolution in the Sceloporus grammicus complex. National Geographic Research 3(3): 343-362.

Sites, J.W., Jr., C.A. Porter, and P. Thompson. 1987. Genetic structure and chromosomal evolution in the Sceloporus grammicus complex. National Geographic Research 3(3): 343-362. Sites, J.W., Jr., P. Thompson, and C.A. Porter. 1988. Cascading chromosomal speciation in lizards: a second look. Pacific Science 42(1-2): 89-104.

Sites, J.W., Jr., P. Thompson, and C.A. Porter. 1988. Cascading chromosomal speciation in lizards: a second look. Pacific Science 42(1-2): 89-104. Skinner, M.P. 1924. The Yellowstone Nature Book. A.C. McClurg Company, Chicago, IL. 221 p.

Skinner, M.P. 1924. The Yellowstone Nature Book. A.C. McClurg Company, Chicago, IL. 221 p. Smith, H.M. 1991b. Three new records of lizards in Ouray County, Colorado. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 26(10): 223.

Smith, H.M. 1991b. Three new records of lizards in Ouray County, Colorado. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 26(10): 223. Spring Creek Coal Company., 1992, Wildlife Monitoring Report. Spring Creek Coal Company 1992 Mining Annual Report. Appendix I.

Spring Creek Coal Company., 1992, Wildlife Monitoring Report. Spring Creek Coal Company 1992 Mining Annual Report. Appendix I. Stebbins, R. C. 2003. A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York. 533 p.

Stebbins, R. C. 2003. A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York. 533 p. Stebbins, R.C. 1948a. Additional observations on home ranges and longevity in the lizard Sceloporus graciosus. Copeia 1948:20-22.

Stebbins, R.C. 1948a. Additional observations on home ranges and longevity in the lizard Sceloporus graciosus. Copeia 1948:20-22. Stebbins, R.C. and H.B. Robinson. 1946. Further analysis of populations of the lizard Sceloporus g. graciosus. University of California (Berkeley) Publications in Zoology 48: 149-168.

Stebbins, R.C. and H.B. Robinson. 1946. Further analysis of populations of the lizard Sceloporus g. graciosus. University of California (Berkeley) Publications in Zoology 48: 149-168. Thompson, L.S. 1984a. Biogeography of Montana: preliminary observations on major faunal and floristic distribution patterns. Abstract. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 43: 40-41.

Thompson, L.S. 1984a. Biogeography of Montana: preliminary observations on major faunal and floristic distribution patterns. Abstract. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 43: 40-41. Thompson, P. and J.W. Sites, Jr. 1986a. Comparison of population structure in chromosomally polytypic and monotypic species of Sceloporus (Sauria: Iguanidae) in relation to chromosomally-mediated speciation. Evolution 40(2): 303-314.

Thompson, P. and J.W. Sites, Jr. 1986a. Comparison of population structure in chromosomally polytypic and monotypic species of Sceloporus (Sauria: Iguanidae) in relation to chromosomally-mediated speciation. Evolution 40(2): 303-314. Thompson, P. and J.W. Sites, Jr. 1986b. Two aberrant karyotypes in the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus): Triploidy and a "supernumerary" oddity. Great Basin Naturalist 46(2): 224-227.

Thompson, P. and J.W. Sites, Jr. 1986b. Two aberrant karyotypes in the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus): Triploidy and a "supernumerary" oddity. Great Basin Naturalist 46(2): 224-227. Thunderbird Wildlife Consulting, Inc., Gillette, WY., 2002, 2001 wildlife monitoring: Big Sky Mine. March 2002.

Thunderbird Wildlife Consulting, Inc., Gillette, WY., 2002, 2001 wildlife monitoring: Big Sky Mine. March 2002. Timken, R. No Date. Amphibians and reptiles of the Beaverhead National Forest. Western Montana College, Dillon, MT. 16 p.

Timken, R. No Date. Amphibians and reptiles of the Beaverhead National Forest. Western Montana College, Dillon, MT. 16 p. Turner, F.B. 1951. A checklist of the reptiles and amphibians of Yellowstone National Park with incidental notes. Yellowstone Nature Notes 25(3): 25-29.

Turner, F.B. 1951. A checklist of the reptiles and amphibians of Yellowstone National Park with incidental notes. Yellowstone Nature Notes 25(3): 25-29. Turner, F.B. 1955. Reptiles and amphibians of Yellowstone National Park. Yellowstone Interpretive Series No. 5. Yellowstone Library and Museum Association. Yellowstone National Park, WY. 40 p.

Turner, F.B. 1955. Reptiles and amphibians of Yellowstone National Park. Yellowstone Interpretive Series No. 5. Yellowstone Library and Museum Association. Yellowstone National Park, WY. 40 p. Waage, B.C. 1998. Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine 1997 annual wildlife monitoring report December 1, 1996 to November 30, 1997 survey period. Western Energy Company, Colstrip, MT.

Waage, B.C. 1998. Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine 1997 annual wildlife monitoring report December 1, 1996 to November 30, 1997 survey period. Western Energy Company, Colstrip, MT. Waage, Bruce C., 1991, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report, 1990 Field Season. September 1991.

Waage, Bruce C., 1991, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report, 1990 Field Season. September 1991. Waage, Bruce C., 1992, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report, 1991 Field Season. December 1992.

Waage, Bruce C., 1992, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report, 1991 Field Season. December 1992. Waage, Bruce C., 1993, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; 1993 Field Season. April 1993.

Waage, Bruce C., 1993, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; 1993 Field Season. April 1993. Waage, Bruce C., 1995, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana:1994 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 1993 - November 30, 1994. February 27, 1995.

Waage, Bruce C., 1995, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana:1994 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 1993 - November 30, 1994. February 27, 1995. Waage, Bruce C., 1996, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: 1995 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 1994 - November 30, 1995. February 28, 1996.

Waage, Bruce C., 1996, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: 1995 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 1994 - November 30, 1995. February 28, 1996. Waage, Bruce C., 1998, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: 1997 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 1996 - November 30, 1997 Survey Period. March 23, 1998.

Waage, Bruce C., 1998, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: 1997 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 1996 - November 30, 1997 Survey Period. March 23, 1998. Waage, Bruce C., 1999, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: 1998 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 1997 - November 30, 1998 Survey Period. February 24, 1999.

Waage, Bruce C., 1999, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: 1998 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 1997 - November 30, 1998 Survey Period. February 24, 1999. Waage, Bruce C., 2000, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: 1999 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 1998 - November 30, 1999. February 2000.

Waage, Bruce C., 2000, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: 1999 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 1998 - November 30, 1999. February 2000. Waage, Bruce C., 2001, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: 2000 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 1999 - November 30, 2000. March 30, 2001.

Waage, Bruce C., 2001, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana: 2000 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 1999 - November 30, 2000. March 30, 2001. Waage, Bruce C., 2002, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana. 2001 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 2000 - November 30, 2001. Febr. 26, 2002.

Waage, Bruce C., 2002, Western Energy Company Rosebud Mine, Colstrip, Montana. 2001 Annual Wildlife Monitoring Report; December 1, 2000 - November 30, 2001. Febr. 26, 2002. Werschkul, D.F. 1982. Species-habitat relationships in an Oregon cold desert lizard community. Great Basin Naturalist 42(3): 380-384.

Werschkul, D.F. 1982. Species-habitat relationships in an Oregon cold desert lizard community. Great Basin Naturalist 42(3): 380-384. Wiens, J.J. and T.W. Reeder. 1997. Phylogeny of the spiny lizards (Sceloporus) based on molecular and morphological evidence. Herpetological Monographs 11:1-101.

Wiens, J.J. and T.W. Reeder. 1997. Phylogeny of the spiny lizards (Sceloporus) based on molecular and morphological evidence. Herpetological Monographs 11:1-101. Woodbury, M. and A.M. Woodbury. 1945. Life-history studies of the sagebrush lizard Sceloporus graciosus graciosus with special reference to cycles in reproduction. Herpetologica 2: 175-196.

Woodbury, M. and A.M. Woodbury. 1945. Life-history studies of the sagebrush lizard Sceloporus graciosus graciosus with special reference to cycles in reproduction. Herpetologica 2: 175-196. Yeager, D.C. 1926. Miscellaneous notes. Yellowstone Nature Notes 3(4): 7.

Yeager, D.C. 1926. Miscellaneous notes. Yellowstone Nature Notes 3(4): 7.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Common Sagebrush Lizard"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Reptiles"