View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Fringed Myotis - Myotis thysanodes

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is uncommon to rare across much of Montana and is facing threats from invasion of White-Nose Syndrome which may cause catastrophic declines

General Description

The Fringed Myotis is a member of the long-eared myotis group. Although similar to Western Long-eared Myotis (Myotis evotis), it is the only species with a well-developed fringe of hairs on the posterior margin of the uropatagium, and is larger than most other Myotis, except in ear size. The robust calcar is not distinctly keeled. The skull is relatively large, with a well-developed sagittal crest, and 38 teeth (dental formula: I 2/3, C 1/1, P 3/3, M 3/3). Color of the pelage varies from yellowish-brown to darker olivaceous tones; color tends to be darker in northern populations. The ears and membranes are blackish-brown and tend to contrast with the pelage. Length of the head and body is 43 to 59 millimeters, length of the tail is 34 to 45 millimeters, length of the ear is 16 to 20 millimeters, length of the forearm is 40 to 47 millimeters, and weight is 5.4 to 10.0 grams. Females are significantly larger in head, body and forearm size (O'Farrell and Studier 1980, Nagorsen and Brigham 1993, Foresman 2012).

Diagnostic Characteristics

The presence of a well-developed fringe of hairs along the posterior edge of the uropatagium is unique among the Myotis found in Montana, including the other long-eared species. The forearm is longer (usually more than 40 millimeters) than all other species of Myotis except some individuals of M. evotis (a long-eared species) and M. volans (a short-eared species with a keeled calcar). The skull is broader than other Myotis species, with a distance across the upper molars more than 6.2 millimeters.

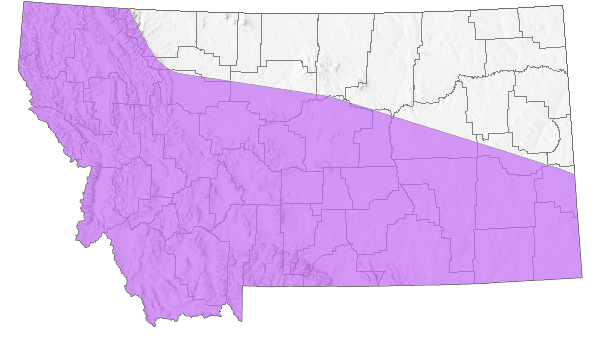

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Global Range

Estimated global breeding range area is: 5,584,919 km

2 (Approximately 5% in Montana)

See information about

iNaturalist Geomodels

iNaturalist Geomodels

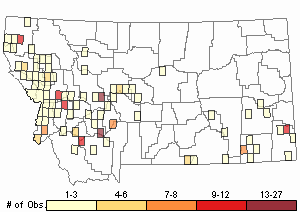

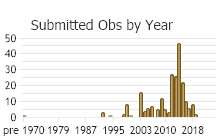

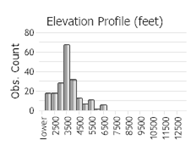

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 228

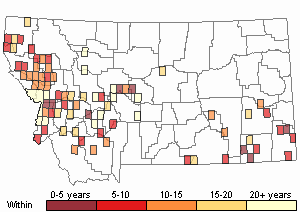

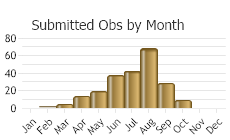

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

No information on movements in Montana is available (Foresman 2012). The Fringed Myotis has been observed in Montana during April through October. While this may be indicative of migration out of the state for winter, a few individuals have been found hibernating in caves.

Habitat

The few Montana records indicate that the habitats in Montana that are used by the Fringed Myotis are similar to other regions in the interior West (Foresman 2012). It has been captured in ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir forest while foraging over willow/cottonwood areas along creeks and over pools, and taken in caves (Lewis and Clark Caverns); one individual was captured in an urban setting in Missoula (Hoffmann et al. 1969, Butts 1993, Dubois 1999).

Habitat information gathered from range-wide studies state the Fringed Myotis is found primarily in desert shrublands, sagebrush-grassland, and woodland habitats (ponderosa pine forest, oak and pine habitats, Douglas-fir), although it has been recorded in spruce-fir habitat in New Mexico. It also occurs at low elevations along the Pacific Coast, and in badlands in the northern Great Plains (Jones et al. 1983, Humes et al. 1999). It roosts in caves, mines, rock crevices, buildings, and other protected sites. Nursery colonies occur in caves, mines, and sometimes buildings (Easterla 1973, O'Farrell and Studier 1980, Jones et al. 1983). Fringed Myotis in riparian areas tend to be more active over intermittent streams with wider channels (5.5 to 10.5 meters) than ones with channels less than 2.0 meters wide (Seidman and Zabel 2001).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Forest and Woodland

Deciduous Forest and Woodland

Low Elevation - Xeric Forest and Woodland

Montane - Subalpine Forest and Woodland

Shrubland

Arid - Saline Shrubland

Foothills - Montane Shrubland

Sagebrush Shrubland

Grassland

Lowland - Prairie Grassland

Montane - Subalpine Grassland

Sparse and Barren

Sparse and Barren

Wetland and Riparian

Alkaline - Saline Wetlands

Alpine Riparian and Wetland

Peatland

Riparian and Wetland Forest

Riparian Shrubland

Wet Meadow and Marsh

Recently Disturbed or Modified

Harvested Forest

Insect-Killed Forest

Introduced Vegetation

Recently Burned

Human Land Use

Developed

Food Habits

Food habits have not been studied in the state. Range-wide information state that Fringed Myotis are insectivorous; beetles occurred in 73% and moths in 36% of fecal pellets in New Mexico (Black 1974). The diet in Oregon included over 40% moths, with lesser amounts of five other insect orders and spiders (Verts and Carraway 1998); moths and beetles have been reported in the diet in South Dakota (Turner and Jones 1968).

The diet in Montana has not been reported or studied. The wings of the Fringed Myotis have a high puncture strength, which is characteristic of bats that forage by gleaning from the ground or near thick or thorny vegetation (O'Farrell and Studier 1980); when in flight, Fringed Myotis often forages close to the vegetative canopy.

Ecology

No ecological information is available for the Fringed Myotis in Montana. Across its range, including the Black Hills region, the known activity period of the Fringed Myotis extends from April through September (O'Farrell and Studier 1980, Jones et al. 1983), with hibernation extending from September to April or early May; activity is greatest during the first two hours after sunset. All Montana records to date (n = 13) have occurred from mid-June to early September. Predators of Fringed Myotis are largely unknown; a domestic cat captured a juvenile in Montana (Hoffmann et al. 1969).

Females generally are found at lower elevations than males (Cryan et al. 2000), perhaps because reproductive individuals need warmer roosts in which to raise young. Males and females form separate colonies in summer, although an occasional male may be found in a maternity colony. Sex ratios in trapping samples may be biased because of sex-related differences in habitat use (Bogan et al. 1996). Individuals in an attic complex maternity colony tended to roost in the open in tightly packed clusters. The Fringed Myotis is found with many other bat species (O'Farrell and Studier 1980, Butts 1993, Choate and Anderson 1997, Dubois 1999), including Townsend's Big-eared Bat (Corynorhinus townsendii), Western Long-eared Myotis (M. evotis), Long-legged Myotis (M. volans), Little Brown Myotis (M. lucifugus), Yuma Myotis (M. yumanensis), Western Small-footed Myotis (M. ciliolabrum), and California Myotis (M. californicus), each of which is present in Montana. However, the ecology of the Fringed Myotis in Montana is largely unknown and has not been studied.

Reproductive Characteristics

There is almost no information on reproduction of the Fringed Myotis in Montana, and no published studies. A juvenile was collected in Missoula County in early September, and an adult female in mid-June in Ravalli County, indicating that reproduction occurs in Montana (Hoffmann et al. 1969).

Information gathered from studies in other areas of the species' range indicate apparently little variation in the timing of reproduction throughout the range. In northeastern New Mexico, mating occurs in fall, ovulation, fertilization, and implantation occur from late April to mid-May, gestation lasts 50 to 60 days, and young are born in late June to mid-July. In South Dakota, pregnant females have been captured in mid-June, lactating females in late July through August, and flying young-of-the-year as early as late July or early August (O'Farrell and Studier 1980, Jones et al. 1983, Bogan et al. 1996). The litter size is 1. Young can fly at 16 to 17 days. Maternity colony sizes range up to several hundred individuals. Individuals may live 11 years or more (Paradiso and Greenhall 1967); the record is 18.3 years (Verts and Carraway 1998).

Management

Although no management measures have been enacted specifically for the protection of Fringed Myotis in Montana, protection of bat roosting habitat through gating of caves and abandoned mines should be beneficial for this species. Protection guidelines and management protocols designated for Townsend's Big-eared Bat (Corynorhinus townsendii) (Pierson et al. 1999) are also appropriate for Fringed Myotis (the two species coexist over much of their ranges) and are recommended as default measures until specific conservation protocols for this species are developed. So little is known about Fringed Myotis in Montana, including its distribution and relative abundance, that standardized surveys of potential roosts and foraging habitats are desirable as the first step to identifying the spatial and temporal context in which this species is present in the state. This basic information will make it easier to design and implement appropriate and effective conservation guidelines to protect important habitats and roosts.

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Black, H.L. 1974. A north temperate bat community: structure and prey populations. Journal of Mammalogy 55:138-157.

Black, H.L. 1974. A north temperate bat community: structure and prey populations. Journal of Mammalogy 55:138-157. Bogan, M. A., J. G. Osborne, and J. A. Clarke. 1996. Observations on bats at Badlands National Park, South Dakota. Prairie Naturalist 28:115-123.

Bogan, M. A., J. G. Osborne, and J. A. Clarke. 1996. Observations on bats at Badlands National Park, South Dakota. Prairie Naturalist 28:115-123. Butts, T.W. 1993. A survey of the bats of the Townsend Ranger District, Helena National Forest, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, Montana. 16 pp.

Butts, T.W. 1993. A survey of the bats of the Townsend Ranger District, Helena National Forest, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, Montana. 16 pp. Choate, J. R. and J. M. Anderson. 1997. Bats of Jewel Cave National Monument, South Dakota. Prairie Naturalist 29:39-47.

Choate, J. R. and J. M. Anderson. 1997. Bats of Jewel Cave National Monument, South Dakota. Prairie Naturalist 29:39-47. Cryan, P. M., M. A. Bogan, and J. S. Altenbach. 2000. Effect of elevation on distribution of female bats in the Black Hills, South Dakota. Journal of Mammalogy 81:719-725.

Cryan, P. M., M. A. Bogan, and J. S. Altenbach. 2000. Effect of elevation on distribution of female bats in the Black Hills, South Dakota. Journal of Mammalogy 81:719-725. Dubois, K. 1999. Region 4 bat surveys: 1998 progress report. Unpublished report, Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks Region 4 Headquarters, Great Falls, Montana. 20 pp.

Dubois, K. 1999. Region 4 bat surveys: 1998 progress report. Unpublished report, Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks Region 4 Headquarters, Great Falls, Montana. 20 pp. Easterla, D. A. 1973. Ecology of the 18 species of Chiroptera at Big Bend National Park, Texas. Part I and II. Northwest Missouri State University Studies 34:1-165.

Easterla, D. A. 1973. Ecology of the 18 species of Chiroptera at Big Bend National Park, Texas. Part I and II. Northwest Missouri State University Studies 34:1-165. Foresman, K.R. 2012. Mammals of Montana. Second edition. Mountain Press Publishing, Missoula, Montana. 429 pp.

Foresman, K.R. 2012. Mammals of Montana. Second edition. Mountain Press Publishing, Missoula, Montana. 429 pp. Hoffmann, R. S., D. L. Pattie and J. F. Bell. 1969. The distribution of some mammals in Montana. II. Bats. Journal of Mammalogy 50(4): 737-741.

Hoffmann, R. S., D. L. Pattie and J. F. Bell. 1969. The distribution of some mammals in Montana. II. Bats. Journal of Mammalogy 50(4): 737-741. Humes, M. L., J. P. Hayes, and M. W. Collopy. 1999. Bat activity in thinned, unthinned, and old-growth forests in western Oregon. Journal of Wildlife Management 63:553-561.

Humes, M. L., J. P. Hayes, and M. W. Collopy. 1999. Bat activity in thinned, unthinned, and old-growth forests in western Oregon. Journal of Wildlife Management 63:553-561. Jones, J.K., D.M. Armstrong, R.S. Hoffmann and C. Jones. 1983. Mammals of the northern Great Plains. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. 379 pp.

Jones, J.K., D.M. Armstrong, R.S. Hoffmann and C. Jones. 1983. Mammals of the northern Great Plains. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. 379 pp. Nagorsen, D.W. and R.M. Brigham. 1993. Bats of British Columbia. Volume I. The Mammals of British Columbia. UBC Press, Vancouver. 164 pp.

Nagorsen, D.W. and R.M. Brigham. 1993. Bats of British Columbia. Volume I. The Mammals of British Columbia. UBC Press, Vancouver. 164 pp. O'Farrell, M.J. and E.H. Studier. 1980. Myotis thysanodes. Mammalian Species 137:1-5.

O'Farrell, M.J. and E.H. Studier. 1980. Myotis thysanodes. Mammalian Species 137:1-5. Paradiso, J. L. and A. M. Greenhall. 1967. Longevity records for American bats. American Midland Naturalist 78:251-252.

Paradiso, J. L. and A. M. Greenhall. 1967. Longevity records for American bats. American Midland Naturalist 78:251-252. Pierson, E.D., M.C. Wackenhut, J.S. Altenbach, P. Bradley, P. Call, D.L. Genter, C.E. Harris, B.L. Keller, B. Lengus, L. Lewis, and B. Luce. 1999. Species conservation assessment and strategy for Townsend's big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii townsendii and Corynorhinus townsendii pallescens). Idaho Conservation Effort, Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Boise, Idaho. 68 pp.

Pierson, E.D., M.C. Wackenhut, J.S. Altenbach, P. Bradley, P. Call, D.L. Genter, C.E. Harris, B.L. Keller, B. Lengus, L. Lewis, and B. Luce. 1999. Species conservation assessment and strategy for Townsend's big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii townsendii and Corynorhinus townsendii pallescens). Idaho Conservation Effort, Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Boise, Idaho. 68 pp. Seidman, V. M. and C. J. Zabel. 2001. Bat activity along intermittent streams in northwestern California. Journal of Mammalogy 82:738-747.

Seidman, V. M. and C. J. Zabel. 2001. Bat activity along intermittent streams in northwestern California. Journal of Mammalogy 82:738-747. Turner, R. W. and J. K. Jones, Jr. 1968. Additional notes on bats from western South Dakota. Southwestern Naturalist 13:444-447.

Turner, R. W. and J. K. Jones, Jr. 1968. Additional notes on bats from western South Dakota. Southwestern Naturalist 13:444-447. Verts, B. J. and L. N. Carraway. 1998. Land mammals of Oregon. University of California Press, Berkeley. xvi + 668 pp.

Verts, B. J. and L. N. Carraway. 1998. Land mammals of Oregon. University of California Press, Berkeley. xvi + 668 pp.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Abernethy, I.M., M.D. Andersen, and D.A. Keinath. 2012. Bats of southern Wyoming: distribution and migration year 2 report. Prepared for the USDI Bureau of Land Management by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming.

Abernethy, I.M., M.D. Andersen, and D.A. Keinath. 2012. Bats of southern Wyoming: distribution and migration year 2 report. Prepared for the USDI Bureau of Land Management by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming. Adams, R.A. 2003. Bats of the Rocky Mountain West: natural history, ecology and conservation. University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO. 289 pp.

Adams, R.A. 2003. Bats of the Rocky Mountain West: natural history, ecology and conservation. University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO. 289 pp. Adams, R.A. and M.A. Hayes. 2008. Water availability and successful lactation by bats as related to climate change in arid regions of western North America. Journal of Animal Ecology 77(6): 1115-1121.

Adams, R.A. and M.A. Hayes. 2008. Water availability and successful lactation by bats as related to climate change in arid regions of western North America. Journal of Animal Ecology 77(6): 1115-1121. Adams, R.A., S.C. Pedersen, K.M. Thibault, J. Jadin, and B. Petru. 2003. Calcium as a Limiting Resource to Insectivorous Bats: Can Water Holes Provide a Supplemental Mineral Source. Journal of Zoology 260(2): 189-194.

Adams, R.A., S.C. Pedersen, K.M. Thibault, J. Jadin, and B. Petru. 2003. Calcium as a Limiting Resource to Insectivorous Bats: Can Water Holes Provide a Supplemental Mineral Source. Journal of Zoology 260(2): 189-194. Agnarsson, I., C.M. Zambrana-Torrelio, N.P. Flores-Saldana, L.J. May-Collado. 2011. A time-calibrated species-level phylogeny of bats (Chiroptera, Mammalia). PLoS Currents Tree of Life. Edition1. RRN1212.

Agnarsson, I., C.M. Zambrana-Torrelio, N.P. Flores-Saldana, L.J. May-Collado. 2011. A time-calibrated species-level phylogeny of bats (Chiroptera, Mammalia). PLoS Currents Tree of Life. Edition1. RRN1212. Amichai, E., G. Blumrosen, and Y. Yovel. 2015. Calling louder and longer: how bats use biosonar under severe acoustic interference from other bats. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, The Royal Society 282(1821): 20152064.

Amichai, E., G. Blumrosen, and Y. Yovel. 2015. Calling louder and longer: how bats use biosonar under severe acoustic interference from other bats. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, The Royal Society 282(1821): 20152064. Arnett, E.B. 2007. Presence, relative abundance, and resource selection of bats in managed forest landscapes in western Oregon. Ph.D. dissertation, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon.

Arnett, E.B. 2007. Presence, relative abundance, and resource selection of bats in managed forest landscapes in western Oregon. Ph.D. dissertation, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon. Bachen, D.A., A.L. McEwan, B.O. Burkholder, S.L. Hilty, S.A. Blum, and B.A. Maxell.. 2018. Bats of Montana: Identification and Natural History. Report to Montana Department of Environmental Quality. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 111pp.

Bachen, D.A., A.L. McEwan, B.O. Burkholder, S.L. Hilty, S.A. Blum, and B.A. Maxell.. 2018. Bats of Montana: Identification and Natural History. Report to Montana Department of Environmental Quality. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 111pp. Bachen, D.A., and B.A. Maxell. 2014. Distribution and status of bird, small mammal, reptile, and amphibian species, South Dakota Field Office-BLM. Report to the Bureau of Land Management, South Dakota Field Office. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana 25 pp. plus appendices.

Bachen, D.A., and B.A. Maxell. 2014. Distribution and status of bird, small mammal, reptile, and amphibian species, South Dakota Field Office-BLM. Report to the Bureau of Land Management, South Dakota Field Office. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana 25 pp. plus appendices. Baker, R.H. and C.J. Phillips. 1965. Mammals from El Nevado de Colima, Mexico. Journal of Mammalogy 46(4): 691-693.

Baker, R.H. and C.J. Phillips. 1965. Mammals from El Nevado de Colima, Mexico. Journal of Mammalogy 46(4): 691-693. Barclay, R.M.R. 1991. Population Structure of Temperate Zone Insectivorous Bats in Relation to Foraging Behavior and Energy Demand. Journal of Animal Ecology 60(1): 165.

Barclay, R.M.R. 1991. Population Structure of Temperate Zone Insectivorous Bats in Relation to Foraging Behavior and Energy Demand. Journal of Animal Ecology 60(1): 165. Bat Conservation International. G4 Harp Trap: Assembly and Advice. 8 p.

Bat Conservation International. G4 Harp Trap: Assembly and Advice. 8 p. Baxter, D.M., J.M. Psyllakis, M.P. Gillingham, and E.L. O'Brien. 2006. Behavioural response of bats to perceived predation risk while foraging. Ethology 112(10): 977-983.

Baxter, D.M., J.M. Psyllakis, M.P. Gillingham, and E.L. O'Brien. 2006. Behavioural response of bats to perceived predation risk while foraging. Ethology 112(10): 977-983. Bell, J.F., G.J. Moore, G.H. Raymond, and C.E. Tibbs. 1962. Characteristics of Rabies in Bats in Montana. American Journal of Public Health 52(8): 1293-1301.

Bell, J.F., G.J. Moore, G.H. Raymond, and C.E. Tibbs. 1962. Characteristics of Rabies in Bats in Montana. American Journal of Public Health 52(8): 1293-1301. Bell, J.F., W.J. Hadlow and W.L. Jellison. 1957. A survey of chiropteran rabies in western Montana. Public Health Reports. 72(1): 16-18.

Bell, J.F., W.J. Hadlow and W.L. Jellison. 1957. A survey of chiropteran rabies in western Montana. Public Health Reports. 72(1): 16-18. Bender, M.J. and G.D. Hartman. 2015. Bat Activity Increases with Barometric Pressure and Temperature During Autumn in Central Georgia. Southeastern Naturalist 14(2): 231-242.

Bender, M.J. and G.D. Hartman. 2015. Bat Activity Increases with Barometric Pressure and Temperature During Autumn in Central Georgia. Southeastern Naturalist 14(2): 231-242. Berthinussen, A. and J. Altringham. 2012. The effect of a major road on bat activity and diversity. Journal of Applied Ecology 49(1): 82-89.

Berthinussen, A. and J. Altringham. 2012. The effect of a major road on bat activity and diversity. Journal of Applied Ecology 49(1): 82-89. Bogan, M.A., and K. Geluso. 1999. Bat roosts and historic structures on National Park Service lands in the Rocky Mountain region. Albuquerque, NM: U.S. Geological Survey, Midcontinent Ecological Science Center, Dept. of Biology, the University of New Mexico. Unpublished report. 25 pp

Bogan, M.A., and K. Geluso. 1999. Bat roosts and historic structures on National Park Service lands in the Rocky Mountain region. Albuquerque, NM: U.S. Geological Survey, Midcontinent Ecological Science Center, Dept. of Biology, the University of New Mexico. Unpublished report. 25 pp Boyce, Mark S. October 8, 1968. First Record Of The Fringe-Tailed Bat, Myotis thysanodes, From Southeastern Wyoming. Southwest. Nat. 25:114-115.

Boyce, Mark S. October 8, 1968. First Record Of The Fringe-Tailed Bat, Myotis thysanodes, From Southeastern Wyoming. Southwest. Nat. 25:114-115. British Columbia Ministry of Environment, Lands, and Parks. 1998. Inventory Methods for Bats; Standards for Components of British Columbia's Biodiversity No. 20. Prepared for the Terrestrial Ecosystems Task Force Resources Inventory Committee. Version 2.0. 58 p.

British Columbia Ministry of Environment, Lands, and Parks. 1998. Inventory Methods for Bats; Standards for Components of British Columbia's Biodiversity No. 20. Prepared for the Terrestrial Ecosystems Task Force Resources Inventory Committee. Version 2.0. 58 p. Butts, T. 1997. Bat surveys Indian Creek Canyon, Elkhorn Mountains, Montana. Continental Divide Wildlife Consulting. Helena, MT 32 pg.

Butts, T. 1997. Bat surveys Indian Creek Canyon, Elkhorn Mountains, Montana. Continental Divide Wildlife Consulting. Helena, MT 32 pg. Butts, T.W. 1993. A preliminary survey of the bats of the Deerlodge National Forest, Montana: 1991. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 35 pp.

Butts, T.W. 1993. A preliminary survey of the bats of the Deerlodge National Forest, Montana: 1991. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 35 pp. Butts, T.W. 1993. A survey of the bats of the Deerlodge National Forest Montana: 1992. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 39 pp.

Butts, T.W. 1993. A survey of the bats of the Deerlodge National Forest Montana: 1992. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 39 pp. Callahan, E.V. and R.D. Drobney. 1997. Selection of summer roosting sites by Indiana bats (Myotis sodalis) in Missouri. Journal of Mammalogy 78(3): 818.

Callahan, E.V. and R.D. Drobney. 1997. Selection of summer roosting sites by Indiana bats (Myotis sodalis) in Missouri. Journal of Mammalogy 78(3): 818. Carlson, J.C. and P. Hendricks. 2001. A Proposal for: Bat Use of Highway Structures: A Pilot Study. Submitted to the Montana Department of Transportation.

Carlson, J.C. and P. Hendricks. 2001. A Proposal for: Bat Use of Highway Structures: A Pilot Study. Submitted to the Montana Department of Transportation. Carlson, J.C. and S.V. Cooper. 2003. Plant and Animal Resources and Ecological Condition of the Forks Ranch Unit of the Padlock Ranch, Big Horn County, Montana and Sheridan County, Wyoming. Unpublished report to The Nature Conservancy Montana Field Office.

Carlson, J.C. and S.V. Cooper. 2003. Plant and Animal Resources and Ecological Condition of the Forks Ranch Unit of the Padlock Ranch, Big Horn County, Montana and Sheridan County, Wyoming. Unpublished report to The Nature Conservancy Montana Field Office. Chester, J.M., N.P. Campbell, K. Karsmizki, and D. Wirtz. 1979. Resource inventory and evaluation. Azure Cave, Montana. BLM unpublished report. 55 pp.

Chester, J.M., N.P. Campbell, K. Karsmizki, and D. Wirtz. 1979. Resource inventory and evaluation. Azure Cave, Montana. BLM unpublished report. 55 pp. Christy, R. E. and S. W. West. 1993. Biology of bats in Douglas-fir forests. U.S.D.A., Forest Serv., Pac. Northw. res. Station, Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-308.

Christy, R. E. and S. W. West. 1993. Biology of bats in Douglas-fir forests. U.S.D.A., Forest Serv., Pac. Northw. res. Station, Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-308. Chung-MacCoubrey, A.L. 2005. Use of pinyon–juniper woodlands by bats in New Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management 204: 209–220.

Chung-MacCoubrey, A.L. 2005. Use of pinyon–juniper woodlands by bats in New Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management 204: 209–220. Clement, M.J., J.M. O'Keefe, and B. Walters. 2015. A method for estimating abundance of mobile populations using telemetry and counts of unmarked animals. Ecosphere 6(10): 184.

Clement, M.J., J.M. O'Keefe, and B. Walters. 2015. A method for estimating abundance of mobile populations using telemetry and counts of unmarked animals. Ecosphere 6(10): 184. Clement, M.J., T.J. Rodhouse, P.C. Ormsbee, J.M. Szewczak, and J.D. Nichols. 2014. Accounting for false-positive acoustic detections of bats using occupancy models. Journal of Applied Ecology 51(5): 1460-1467.

Clement, M.J., T.J. Rodhouse, P.C. Ormsbee, J.M. Szewczak, and J.D. Nichols. 2014. Accounting for false-positive acoustic detections of bats using occupancy models. Journal of Applied Ecology 51(5): 1460-1467. Cockrum, E.L., B. Musgrove, and Y. Peteryszyn. 1996. Bats of Mohave County, Arizona: populations and movements. Occasional Papers of The Museum, Texas Tech University 157: 1-71.

Cockrum, E.L., B. Musgrove, and Y. Peteryszyn. 1996. Bats of Mohave County, Arizona: populations and movements. Occasional Papers of The Museum, Texas Tech University 157: 1-71. Coleman, J.L. and R.R. Barclay. 2013. Prey availability and foraging activity of grassland bats in relation to urbanization. Journal of Mammalogy 94(5): 1111-1122.

Coleman, J.L. and R.R. Barclay. 2013. Prey availability and foraging activity of grassland bats in relation to urbanization. Journal of Mammalogy 94(5): 1111-1122. Constantine, D.G., G.L. Humphrey, and T.B Herbenick. 1979. Rabies in Myotis thysanodes, Lasiurus ega, Euderma maculatum, and Eumops perotis in California. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 15(2): 343-345.

Constantine, D.G., G.L. Humphrey, and T.B Herbenick. 1979. Rabies in Myotis thysanodes, Lasiurus ega, Euderma maculatum, and Eumops perotis in California. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 15(2): 343-345. Corbett, J. 2011. Evaluation and management of select natural cave and abandoned mine features of the Lewis & Clark and Helena National Forests, Montana. Bat Conservation International. 18pp plus appendices.

Corbett, J. 2011. Evaluation and management of select natural cave and abandoned mine features of the Lewis & Clark and Helena National Forests, Montana. Bat Conservation International. 18pp plus appendices. Cryan, P.M., M.A. Bogan, G.M. Yanega. 2001. Roosting habits of four bat species in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Acta Chiropterologica 3(1): 43-52.

Cryan, P.M., M.A. Bogan, G.M. Yanega. 2001. Roosting habits of four bat species in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Acta Chiropterologica 3(1): 43-52. Cvikel, N., E. Levin, E. Hurme, I. Borissov, A. Boonman, E. Amichai, and Y. Yovel. 2015. On-board recordings reveal no jamming avoidance in wild bats. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, The Royal Society 282(1798).

Cvikel, N., E. Levin, E. Hurme, I. Borissov, A. Boonman, E. Amichai, and Y. Yovel. 2015. On-board recordings reveal no jamming avoidance in wild bats. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, The Royal Society 282(1798). Davis, R. 1966. Homing performance and homing ability in bats. Ecological Monographs 36(3): 201-237.

Davis, R. 1966. Homing performance and homing ability in bats. Ecological Monographs 36(3): 201-237. Davis, W.B. 1937. Some mammals from western Montana and eastern Idaho. The Murrelet 18(2): 22-27.

Davis, W.B. 1937. Some mammals from western Montana and eastern Idaho. The Murrelet 18(2): 22-27. Department of Health and Environmental Sciences Food and Consumer Safety Bureau. 1981. Montana Bats Part I: Control. Vector Control Bulletin Number 2. 6 p.

Department of Health and Environmental Sciences Food and Consumer Safety Bureau. 1981. Montana Bats Part I: Control. Vector Control Bulletin Number 2. 6 p. Department of Health and Environmental Sciences Food and Consumer Safety Bureau. 1981. Montana Bats Part II: Identification and Biology. Vector Control Bulletin Number 2A. 10 p.

Department of Health and Environmental Sciences Food and Consumer Safety Bureau. 1981. Montana Bats Part II: Identification and Biology. Vector Control Bulletin Number 2A. 10 p. DuBois, K. 2000. Species occurrence and Distribution of Bats in North Central Montana: Range Map Changes Resulting from Two Years of Field Surveys. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 6(4): 376.

DuBois, K. 2000. Species occurrence and Distribution of Bats in North Central Montana: Range Map Changes Resulting from Two Years of Field Surveys. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 6(4): 376. Ducummon, S.L. 1997. The North American bats and mines project: a cooperative approach for integrating bat conservation and mine-land reclamation. Paper presented at the 1997 National Meeting of the American Society for Mining and Reclamation, Austin, Texas.

Ducummon, S.L. 1997. The North American bats and mines project: a cooperative approach for integrating bat conservation and mine-land reclamation. Paper presented at the 1997 National Meeting of the American Society for Mining and Reclamation, Austin, Texas. Duff, A.A. and T.E. Morrell. 2007. Predictive Occurrence Models for Bat Species in California. Journal of Wildlife Management 71(3): 693-700.

Duff, A.A. and T.E. Morrell. 2007. Predictive Occurrence Models for Bat Species in California. Journal of Wildlife Management 71(3): 693-700. Feigley, H.P. 1998. An Examination of the Issues and Feasibility of Conducting Surveys of Abandoned Mines for Bats. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 12 p.

Feigley, H.P. 1998. An Examination of the Issues and Feasibility of Conducting Surveys of Abandoned Mines for Bats. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 12 p. Feigley, H.P., M. Brown, S. Martinez, and K. Schletz. 1997.Assessment of mines for importance to bat species of concern, southwestern Montana. Report to: U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, Midcontinent Ecological Science Center; 4512 McMurry Ave., Fort Collins, CO 80525-3400. 9pp.

Feigley, H.P., M. Brown, S. Martinez, and K. Schletz. 1997.Assessment of mines for importance to bat species of concern, southwestern Montana. Report to: U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, Midcontinent Ecological Science Center; 4512 McMurry Ave., Fort Collins, CO 80525-3400. 9pp. Fenton, M.B. 1990. The Foraging Behavior and Ecology of Animal-Eating Bats. Canadian Journal of Zoology 68(3): 411-422.

Fenton, M.B. 1990. The Foraging Behavior and Ecology of Animal-Eating Bats. Canadian Journal of Zoology 68(3): 411-422. Fenton, M.B. 2003. Science and the conservation of bats: where to next? Wildlife Society Bulletin 31(1) 6-15.

Fenton, M.B. 2003. Science and the conservation of bats: where to next? Wildlife Society Bulletin 31(1) 6-15. Flath, D. L. 1984. Vertebrate species of special interest or concern. Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes. Spec. Publ. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, Helena. 76 pp.

Flath, D. L. 1984. Vertebrate species of special interest or concern. Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes. Spec. Publ. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, Helena. 76 pp. Flath, D.L. 1979. Nongame species of special interest or concern: Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes. Wildlife Division, Montana Department of Fish and Game. Helena, MT.

Flath, D.L. 1979. Nongame species of special interest or concern: Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes. Wildlife Division, Montana Department of Fish and Game. Helena, MT. Foresman, K.R. 2001. The wild mammals of Montana. American Society of Mammalogists, Special Publication Number 12. Lawrence, KS. 278 pp.

Foresman, K.R. 2001. The wild mammals of Montana. American Society of Mammalogists, Special Publication Number 12. Lawrence, KS. 278 pp. Geluso, K. 2007. Winter activity of bats over water and along flyways in New Mexico. Southwestern Naturalist 52(4): 482-492.

Geluso, K. 2007. Winter activity of bats over water and along flyways in New Mexico. Southwestern Naturalist 52(4): 482-492. Geluso, K., and L.N. Mink. 2009. Use of Bridges by Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in the Rio Grande Valley, New Mexico. Southwestern Naturalist, 54(4), 421-429.

Geluso, K., and L.N. Mink. 2009. Use of Bridges by Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in the Rio Grande Valley, New Mexico. Southwestern Naturalist, 54(4), 421-429. Genoways, H. H., and J. K. Jones, Jr. 1972. Mammals from southwestern North Dakota. Occasional Papers, The Museum, Texas Tech University 6:1-36.

Genoways, H. H., and J. K. Jones, Jr. 1972. Mammals from southwestern North Dakota. Occasional Papers, The Museum, Texas Tech University 6:1-36. Genter, D. L. 1986. Wintering bats of the upper Snake River plain: occurrence in lava-tube caves. Great Basin Naturalist 46(2):241-244.

Genter, D. L. 1986. Wintering bats of the upper Snake River plain: occurrence in lava-tube caves. Great Basin Naturalist 46(2):241-244. Genter, D.L. and K.A. Jurist. 1995. Bats of Montana. Guide for Assessing Mines for Bats Workshop, June 14-15, 1995, Helena, MT, hosted by Montana Department of State Lands and the Abandoned Mine Reclamation Bureau. Montana Natural Heritage Program. 11 pp.

Genter, D.L. and K.A. Jurist. 1995. Bats of Montana. Guide for Assessing Mines for Bats Workshop, June 14-15, 1995, Helena, MT, hosted by Montana Department of State Lands and the Abandoned Mine Reclamation Bureau. Montana Natural Heritage Program. 11 pp. Glass, P.J. and W.L. Gannon. 1994. Description of M. uropataginalis (a new muscle), with Additional Comments from a Microscopy Study of the Uropatagium of the Fringed Myotis (Myotis thysanodes). Canadian Journal of Zoology 72(10): 1752-1754

Glass, P.J. and W.L. Gannon. 1994. Description of M. uropataginalis (a new muscle), with Additional Comments from a Microscopy Study of the Uropatagium of the Fringed Myotis (Myotis thysanodes). Canadian Journal of Zoology 72(10): 1752-1754 Griscom, H.R. and D.A. Keinath. 2011. Inventory and status of bats at Devils Tower National Monument. Report prepared for the USDI National Park Service by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database. University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming.

Griscom, H.R. and D.A. Keinath. 2011. Inventory and status of bats at Devils Tower National Monument. Report prepared for the USDI National Park Service by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database. University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming. Griscom, H.R., M.D. Anderson, and D.A. Keinath. 2012. Bats of southern Wyoming: distribution and migration, year 1 report. Prepared for the USDI Bureau of Land Management by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database. University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming.

Griscom, H.R., M.D. Anderson, and D.A. Keinath. 2012. Bats of southern Wyoming: distribution and migration, year 1 report. Prepared for the USDI Bureau of Land Management by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database. University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming. Hagen, E.M. and J.L. Sabo. 2011. A landscape perspective on bat foraging along rivers: does channel confinement and insect availability influence the response of bats to aquatic resources in riverine landscapes? Oecologia 166(3): 751-760.

Hagen, E.M. and J.L. Sabo. 2011. A landscape perspective on bat foraging along rivers: does channel confinement and insect availability influence the response of bats to aquatic resources in riverine landscapes? Oecologia 166(3): 751-760. Hall, E.R. 1981. The mammals of North America, volumes I and II. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. 1181 pp.

Hall, E.R. 1981. The mammals of North America, volumes I and II. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. 1181 pp. Hanauska-Brown, L., B.A. Maxell, A. Petersen, and S. Story. 2014. Diversity Monitoring in Montana 2008-2010 Final Report. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Helena, MT. 78 pp.

Hanauska-Brown, L., B.A. Maxell, A. Petersen, and S. Story. 2014. Diversity Monitoring in Montana 2008-2010 Final Report. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Helena, MT. 78 pp. Harmata, A., D. Flath, R. Hazlewood, and S. Milodragovich. 2002. Initial Site Evaluation for Wind Resource Development in Montana: An Index Relative to Potential Impacts on Vertebrate Wildlife. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 8(4): 253-254.

Harmata, A., D. Flath, R. Hazlewood, and S. Milodragovich. 2002. Initial Site Evaluation for Wind Resource Development in Montana: An Index Relative to Potential Impacts on Vertebrate Wildlife. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 8(4): 253-254. Harvey, M.J., J.S. Altenbach, and T.L. Best. 2011. Bats of the United States and Canada. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. p. 202

Harvey, M.J., J.S. Altenbach, and T.L. Best. 2011. Bats of the United States and Canada. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. p. 202 Hayes, M.A. and R.A. Adams. 2014. Geographic and elevational distribution of fringed myotis (Myotis thysanodes) in Colorado. Western North American Naturalist 74(4): 446-455.

Hayes, M.A. and R.A. Adams. 2014. Geographic and elevational distribution of fringed myotis (Myotis thysanodes) in Colorado. Western North American Naturalist 74(4): 446-455. Hayes, M.A. and R.A. Adams. 2015. Maternity roost selection by fringed myotis in Colorado. Western North American Naturalist 74(4): 460-473.

Hayes, M.A. and R.A. Adams. 2015. Maternity roost selection by fringed myotis in Colorado. Western North American Naturalist 74(4): 460-473. Hein, C.D., S.B. Castleberry, and K.V. Miller. 2009. Site-occupancy of bats in relation to forested corridors. Forest Ecology and Management 257(4): 1200-1207.

Hein, C.D., S.B. Castleberry, and K.V. Miller. 2009. Site-occupancy of bats in relation to forested corridors. Forest Ecology and Management 257(4): 1200-1207. Hendricks, P. 1997. Mine assessments for bat activity, Garnet Resource Area, BLM: 1997. Unpublished report to USDI, Bureau of Land Management. 17pp.

Hendricks, P. 1997. Mine assessments for bat activity, Garnet Resource Area, BLM: 1997. Unpublished report to USDI, Bureau of Land Management. 17pp. Hendricks, P. 1998. Bats surveys of Azure Cave and the Little Rocky Mountains: 1997-1998. November 1998.

Hendricks, P. 1998. Bats surveys of Azure Cave and the Little Rocky Mountains: 1997-1998. November 1998. Hendricks, P. 1999. Effect of gate installation on continued use by bats of four abandoned mine workings in western Montana. Unpublished report to Montana Department of Environmental Quality. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 13 pp.

Hendricks, P. 1999. Effect of gate installation on continued use by bats of four abandoned mine workings in western Montana. Unpublished report to Montana Department of Environmental Quality. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 13 pp. Hendricks, P. 1999. Mine Assessments for Bat Activity, Helena National Forest: 1999. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 12 pp.

Hendricks, P. 1999. Mine Assessments for Bat Activity, Helena National Forest: 1999. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 12 pp. Hendricks, P. 2000. Assessment of abandoned mines for bat use on Bureau of Land Management lands in the Philipsburg, Montana area: 1999. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT.13pp.

Hendricks, P. 2000. Assessment of abandoned mines for bat use on Bureau of Land Management lands in the Philipsburg, Montana area: 1999. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT.13pp. Hendricks, P. 2000. Bat survey along the Norris-Madison Junction Road corridor, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, 1999. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 15pp.

Hendricks, P. 2000. Bat survey along the Norris-Madison Junction Road corridor, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, 1999. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 15pp. Hendricks, P. 2000. Preliminary bat inventory of caves and abandoned mines on BLM lands, Judith Mountains, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 21 pp.

Hendricks, P. 2000. Preliminary bat inventory of caves and abandoned mines on BLM lands, Judith Mountains, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 21 pp. Hendricks, P. 2003. Assessment of Selected Abandoned Mines for Use by Bats in the Garnet and Avon Areas: 2002. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 12 p.

Hendricks, P. 2003. Assessment of Selected Abandoned Mines for Use by Bats in the Garnet and Avon Areas: 2002. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 12 p. Hendricks, P. and B.A. Maxell. 2005. Bat Surveys on USFS Northern Region Lands in Montana: 2005. Report to the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 12 pp. plus appendices.

Hendricks, P. and B.A. Maxell. 2005. Bat Surveys on USFS Northern Region Lands in Montana: 2005. Report to the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 12 pp. plus appendices. Hendricks, P. and D. Kampwerth. 2001. Roost environments for bats using abandoned mines in southwestern Montana : a preliminary assessment. Report to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 19 pp.

Hendricks, P. and D. Kampwerth. 2001. Roost environments for bats using abandoned mines in southwestern Montana : a preliminary assessment. Report to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 19 pp. Hendricks, P. and D.L. Genter. 1997. Bat surveys of Azure Cave and the Little Rocky Mountains: 1996. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 25 pp.

Hendricks, P. and D.L. Genter. 1997. Bat surveys of Azure Cave and the Little Rocky Mountains: 1996. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 25 pp. Hendricks, P. and J.C. Carlson. 2001. Bat use of abandoned mines in the Pryor Mountains. Report to the Montana Department of Environmental Quality, Mine Waste Cleanup Bureau. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, Montana. 8 pp.

Hendricks, P. and J.C. Carlson. 2001. Bat use of abandoned mines in the Pryor Mountains. Report to the Montana Department of Environmental Quality, Mine Waste Cleanup Bureau. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, Montana. 8 pp. Hendricks, P. and L.M. Hendricks. 2010. Water Aquistion During Daylight by Free-Ranging Myotis Bats. Northwestern Naturalist 91(3): 336-338.

Hendricks, P. and L.M. Hendricks. 2010. Water Aquistion During Daylight by Free-Ranging Myotis Bats. Northwestern Naturalist 91(3): 336-338. Hendricks, P., B.A. Maxell, S. Lenard, C. Currier and J. Johnson. 2006. Riparian Bat Surveys in Eastern Montana. A report to the USDI Bureau of Land Management, Montana State Office. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 13 pp. plus appendices.

Hendricks, P., B.A. Maxell, S. Lenard, C. Currier and J. Johnson. 2006. Riparian Bat Surveys in Eastern Montana. A report to the USDI Bureau of Land Management, Montana State Office. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 13 pp. plus appendices. Hendricks, P., C. Currier, and J. Carlson. 2004. Bats of the BLM Billings Field Office in south-central Montana, with emphasis on the Pryor Mountains. Report to Bureau of Land Management Billings Field Office. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 19 pp. + appendices.

Hendricks, P., C. Currier, and J. Carlson. 2004. Bats of the BLM Billings Field Office in south-central Montana, with emphasis on the Pryor Mountains. Report to Bureau of Land Management Billings Field Office. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 19 pp. + appendices. Hendricks, P., D. Kampwerth and M. Brown. 1999. Assessment of abandoned mines for bat use on Bureau of Land Management lands in southwestern Montana: 1997-1998. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 29 pp.

Hendricks, P., D. Kampwerth and M. Brown. 1999. Assessment of abandoned mines for bat use on Bureau of Land Management lands in southwestern Montana: 1997-1998. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 29 pp. Hendricks, P., K. Jurist, D.L. Genter, and J.D. Reichel. 1995. Bat survey of the Sioux District, Custer National Forest: 1994. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, Montana. 41 pp.

Hendricks, P., K. Jurist, D.L. Genter, and J.D. Reichel. 1995. Bat survey of the Sioux District, Custer National Forest: 1994. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, Montana. 41 pp. Hendricks, P., K.A. Jurist, D.L. Genter and J.D. Reichel. 1996. Bats of the Kootenai National Forest, Montana. Unpublished report. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 99 pp.

Hendricks, P., K.A. Jurist, D.L. Genter and J.D. Reichel. 1996. Bats of the Kootenai National Forest, Montana. Unpublished report. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 99 pp. Hendricks, P., K.A. Jurist, D.L. Genter, and J.D. Reichel. 1995. Bat survey of the Kootenai National Forest, Montana: 1994. MTNHP report.

Hendricks, P., K.A. Jurist, D.L. Genter, and J.D. Reichel. 1995. Bat survey of the Kootenai National Forest, Montana: 1994. MTNHP report. Hendricks, P., S. Lenard, C. Currier and J. Johnson. 2005. Bat Use of Highway Bridges in South-Central Montana. FHWA/MT-05-007/8159. Final Report prepared for the Montana Department of Transportation, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration, prepared by the Montana Natural Heritage Program.

Hendricks, P., S. Lenard, C. Currier and J. Johnson. 2005. Bat Use of Highway Bridges in South-Central Montana. FHWA/MT-05-007/8159. Final Report prepared for the Montana Department of Transportation, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration, prepared by the Montana Natural Heritage Program. Hendricks, P., S. Lenard, C. Currier, and B.A. Maxell. 2007. Filling the distribution gaps for small mammals in Montana. Helena, MT.: Montana Natural Heritage Program.

Hendricks, P., S. Lenard, C. Currier, and B.A. Maxell. 2007. Filling the distribution gaps for small mammals in Montana. Helena, MT.: Montana Natural Heritage Program. Hendricks, Paul. 2012. Winter Records of Bats in Montana. Northwestern Naturalist. 93:154-162.

Hendricks, Paul. 2012. Winter Records of Bats in Montana. Northwestern Naturalist. 93:154-162. Hill J.E. and J.D. Smith: 1984. Bats: a natural history. Univ. Texas Press Austin. 243 pp.

Hill J.E. and J.D. Smith: 1984. Bats: a natural history. Univ. Texas Press Austin. 243 pp. Hilty, S.L. 2020. Characterizing summer roosts of male little brown Myotis (Myotis lucifugus) in lodgepole pine-dominated forests. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 70 p.

Hilty, S.L. 2020. Characterizing summer roosts of male little brown Myotis (Myotis lucifugus) in lodgepole pine-dominated forests. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 70 p. Hinman, K.E. and T.K. Snow, eds. 2003. Arizona Bat Conservation Strategic Plan. Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Program Technical Report 213. Arizona Game and Fish Department, Phoenix, Arizona.

Hinman, K.E. and T.K. Snow, eds. 2003. Arizona Bat Conservation Strategic Plan. Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Program Technical Report 213. Arizona Game and Fish Department, Phoenix, Arizona. Holroyd, S.L., V.J. Craig, and P. Govindarajulu. 2016. Best Management Practices for Bats in British Columbia. Ministry of Environment, Victoria, BC. 301pp.

Holroyd, S.L., V.J. Craig, and P. Govindarajulu. 2016. Best Management Practices for Bats in British Columbia. Ministry of Environment, Victoria, BC. 301pp. Humphrey, S. R. 1975. Nursery roosts and community diversity of Nearctic bats. Journal of Mammalogy 56:321-346.

Humphrey, S. R. 1975. Nursery roosts and community diversity of Nearctic bats. Journal of Mammalogy 56:321-346. Jean, C., P. Hendricks, M. Jones, S. Cooper, and J. Carlson. 2002. Ecological communities on the Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge: inventory and review of aspen and wetland systems. Report to Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge.

Jean, C., P. Hendricks, M. Jones, S. Cooper, and J. Carlson. 2002. Ecological communities on the Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge: inventory and review of aspen and wetland systems. Report to Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge. Jiang, T., H. Wu, J. Feng. 2015. Patterns and causes of geographic variation in bat echolocation pulses. Integrative Zoology 10(3): 241-256.

Jiang, T., H. Wu, J. Feng. 2015. Patterns and causes of geographic variation in bat echolocation pulses. Integrative Zoology 10(3): 241-256. Jones, J.K. Jr. and Goneways, H.H. 1967. A new subspecies of the fringe-tailed bat, Myotis thysanedes, from the Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming. J. Mammal. 48(2):231-235.

Jones, J.K. Jr. and Goneways, H.H. 1967. A new subspecies of the fringe-tailed bat, Myotis thysanedes, from the Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming. J. Mammal. 48(2):231-235. Jones, J.K., Jr., R.P. Lampe, C.A. Spenrath, and T.H. Kunz. 1973. Notes on the distribution and natural history of bats in southeastern Montana. Occasional papers (Texas Tech University Museum) 15:1-11.

Jones, J.K., Jr., R.P. Lampe, C.A. Spenrath, and T.H. Kunz. 1973. Notes on the distribution and natural history of bats in southeastern Montana. Occasional papers (Texas Tech University Museum) 15:1-11. Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. Keeley, B. W., and M. D. Tuttle. 1999. “Bats in American Bridges.” Resource Publication No. 4. Bat Conservation International. Austin, TX. 41 p.

Keeley, B. W., and M. D. Tuttle. 1999. “Bats in American Bridges.” Resource Publication No. 4. Bat Conservation International. Austin, TX. 41 p. Keinath, D. 2004. Bat and Terrestrial Mammal Inventories in the Greater Yellowstone Network: A progress report. Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, Laramie, WY. 17 pp.

Keinath, D. 2004. Bat and Terrestrial Mammal Inventories in the Greater Yellowstone Network: A progress report. Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, Laramie, WY. 17 pp. Keinath, D. 2005. Supplementary Mammal Inventory of Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area. Final Report. Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, Laramie, WY. 21 pp.

Keinath, D. 2005. Supplementary Mammal Inventory of Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area. Final Report. Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, Laramie, WY. 21 pp. Keinath, D.A. 2001. Bat Habitat Delineation and Survey Suggestions for Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area. Unpublished report prepared by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database for the North American Bat Conservation Partnership.

Keinath, D.A. 2001. Bat Habitat Delineation and Survey Suggestions for Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area. Unpublished report prepared by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database for the North American Bat Conservation Partnership. Keinath, D.A. 2003. Species assessment for fringed myotis (Myotis thysanodes) in Wyoming. Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY.

Keinath, D.A. 2003. Species assessment for fringed myotis (Myotis thysanodes) in Wyoming. Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY. Keinath, D.A. 2004. Fringed Myotis (Myotis thysanodes): a Technical Conservation Assessment. Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY.

Keinath, D.A. 2004. Fringed Myotis (Myotis thysanodes): a Technical Conservation Assessment. Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY. Keinath, D.A. 2005. A bat Conservation Evaluation for White Grass Ranch, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. Unpublished report for Grand Teton National Park by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Data Base, Laramie, WY.

Keinath, D.A. 2005. A bat Conservation Evaluation for White Grass Ranch, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. Unpublished report for Grand Teton National Park by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Data Base, Laramie, WY. Keinath, D.A. 2007. Yellowstone's World of Bats: Taking Inventory of Yellowstone's Night Life. Yellowstone Science 15: 3-13.

Keinath, D.A. 2007. Yellowstone's World of Bats: Taking Inventory of Yellowstone's Night Life. Yellowstone Science 15: 3-13. Kingston, T., G. Jones, Z. Akbar, and T.H. Kunz. 2003. Alternation of echolocation calls in 5 species of aerial-feeding insectivorous bats from Malaysia. Journal of Mammalogy 84(1): 205-215.

Kingston, T., G. Jones, Z. Akbar, and T.H. Kunz. 2003. Alternation of echolocation calls in 5 species of aerial-feeding insectivorous bats from Malaysia. Journal of Mammalogy 84(1): 205-215. Kubista, C.E. and A. Bruckner. 2015. Importance of urban trees and buildings as daytime roosts for bats. Biologia 70(11): 1545-1552.

Kubista, C.E. and A. Bruckner. 2015. Importance of urban trees and buildings as daytime roosts for bats. Biologia 70(11): 1545-1552. Kudray, G.M., P. Hendricks, E. Crowe, and S.V. Cooper. 2004. Riparian forests of the Wild and Scenic Missouri River: ecology and management. Prepared for Lewistown Field Office, Bureau of Land Management, Lewistown, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 29 pp. plus appendices.

Kudray, G.M., P. Hendricks, E. Crowe, and S.V. Cooper. 2004. Riparian forests of the Wild and Scenic Missouri River: ecology and management. Prepared for Lewistown Field Office, Bureau of Land Management, Lewistown, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 29 pp. plus appendices. Kuenzi, A. J., G. T. Downard, and M. L. Morrison. 1999. Bat distribution and hibernacula use in west central Nevada. Great Basin Naturalist 59:213-220.

Kuenzi, A. J., G. T. Downard, and M. L. Morrison. 1999. Bat distribution and hibernacula use in west central Nevada. Great Basin Naturalist 59:213-220. Kunz, T. H. (ed). 1988. Ecological and behavioral methods for the study of bats. Smithsonian Inst., Washington D.C., 533 pp.

Kunz, T. H. (ed). 1988. Ecological and behavioral methods for the study of bats. Smithsonian Inst., Washington D.C., 533 pp. Kunz, T.H. and M.B. Fenton. 2003. Bat Ecology. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press. p. 1-745.

Kunz, T.H. and M.B. Fenton. 2003. Bat Ecology. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press. p. 1-745. Kunz, T.H. and P.A. Racey. 1998. Bat biology and conservation. International Bat Research Conference 1995. Boston University. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Kunz, T.H. and P.A. Racey. 1998. Bat biology and conservation. International Bat Research Conference 1995. Boston University. Smithsonian Institution Press. Lacki, M.J. and M.D. Baker. 2007. Day Roosts of Female Fringed Myotis (Myotis thysanodes) in Xeric Forests of the Pacific Northwest. Journal of Mammalogy 88(4): 967-973.

Lacki, M.J. and M.D. Baker. 2007. Day Roosts of Female Fringed Myotis (Myotis thysanodes) in Xeric Forests of the Pacific Northwest. Journal of Mammalogy 88(4): 967-973. LaMarr, S. and A.J. Kuenzi. 2011. Bat species presence in southwestern Montana. Intermountain Journal of Sciences. 17:1-4. Pp 14-19.

LaMarr, S. and A.J. Kuenzi. 2011. Bat species presence in southwestern Montana. Intermountain Journal of Sciences. 17:1-4. Pp 14-19. Lampe, R.P., J.K. Jones Jr., R.S. Hoffmann, and E.C. Birney. 1974. The mammals of Carter County, southeastern Montana. Occa. Pap. Mus. Nat. Hist. Univ. Kan. 25:1-39.

Lampe, R.P., J.K. Jones Jr., R.S. Hoffmann, and E.C. Birney. 1974. The mammals of Carter County, southeastern Montana. Occa. Pap. Mus. Nat. Hist. Univ. Kan. 25:1-39. Lemke, T. 1991. Big Sky UFOs. Montana Outdoors 22(6):2-7.

Lemke, T. 1991. Big Sky UFOs. Montana Outdoors 22(6):2-7. Lenard, S. and P. Hendricks. 2012. Bat Surveys at Army Corps of Engineers Libby Dam, Libby, Montana 2011. A report to the US Army Corps of Engineers, Libby Dam. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 21 pp.

Lenard, S. and P. Hendricks. 2012. Bat Surveys at Army Corps of Engineers Libby Dam, Libby, Montana 2011. A report to the US Army Corps of Engineers, Libby Dam. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 21 pp. Lenard, S., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks, and C. Currier. 2007. Bat Surveys on USFS Northern Region 1 Lands in Montana: 2006. Report to the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 23 pp. plus appendices.

Lenard, S., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks, and C. Currier. 2007. Bat Surveys on USFS Northern Region 1 Lands in Montana: 2006. Report to the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. 23 pp. plus appendices. Lenard, S., P. Hendricks, and B.A. Maxell. 2009. Bat surveys on USFS Northern Region lands in Montana: 2007. A report to the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region. Helena, MT. Montana Natural Heritage Program. 21 pp plus appendices.

Lenard, S., P. Hendricks, and B.A. Maxell. 2009. Bat surveys on USFS Northern Region lands in Montana: 2007. A report to the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region. Helena, MT. Montana Natural Heritage Program. 21 pp plus appendices. Lewis, S. E. 1995. “Roost Fidelity of Bats: a Review.” Journal of Mammalogy 76:481-496.

Lewis, S. E. 1995. “Roost Fidelity of Bats: a Review.” Journal of Mammalogy 76:481-496. Lilley, T.M., J.S. Johnson, L. Ruokolainen, E.J. Rogers, C.A. Wilson, S.M. Schell, K.A. Field, and D.M. Reeder. 2016. White-nose syndrome survivors do not exhibit frequent arousals associated with Pseudogymnoascus destructans infection. Frontiers in Zoology 13(1): 1.

Lilley, T.M., J.S. Johnson, L. Ruokolainen, E.J. Rogers, C.A. Wilson, S.M. Schell, K.A. Field, and D.M. Reeder. 2016. White-nose syndrome survivors do not exhibit frequent arousals associated with Pseudogymnoascus destructans infection. Frontiers in Zoology 13(1): 1. Madson, M. and G. Hanson. 1992. Bat hibernaculum search in the Pryor Mountains, southcentral Montana (Draft). Montana Natural Heritage Program. 35 pp.

Madson, M. and G. Hanson. 1992. Bat hibernaculum search in the Pryor Mountains, southcentral Montana (Draft). Montana Natural Heritage Program. 35 pp. Madson. M. 1990. Tate-Potter Cave. Unpublished report, with maps. 6 pp.

Madson. M. 1990. Tate-Potter Cave. Unpublished report, with maps. 6 pp. Manning, R.W. and J.K. Jones, Jr. 1988. A new subspecies of fringed myotis, Myotis thysanodes, from the northwestern coast of the United States. Occasional Papers Museum Texas Tech University No. 123:1-6.

Manning, R.W. and J.K. Jones, Jr. 1988. A new subspecies of fringed myotis, Myotis thysanodes, from the northwestern coast of the United States. Occasional Papers Museum Texas Tech University No. 123:1-6. Martinez, S. 1999. Evaluation of selected bat habitat sites along the Mammoth-Norris grand loop road corridor, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, 1997-1998. [Unpublished report submitted to the Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT]. 16pp.

Martinez, S. 1999. Evaluation of selected bat habitat sites along the Mammoth-Norris grand loop road corridor, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, 1997-1998. [Unpublished report submitted to the Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT]. 16pp. Mathews, F., N. Roche, T. Aughney, N. Jones, J. Day, J. Baker, and S. Langton. 2015. Barriers and benefits: implications of artificial night-lighting for the distribution of common bats in Britain and Ireland. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 370(1667): 20140124.

Mathews, F., N. Roche, T. Aughney, N. Jones, J. Day, J. Baker, and S. Langton. 2015. Barriers and benefits: implications of artificial night-lighting for the distribution of common bats in Britain and Ireland. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 370(1667): 20140124. Matthews, W. L., and J. E. Swenson. 1982. The mammals of east-central Montana. Proc. Mont. Acad. Sci. 41:1-13.

Matthews, W. L., and J. E. Swenson. 1982. The mammals of east-central Montana. Proc. Mont. Acad. Sci. 41:1-13. Maxell, B.A. 2016. Northern Goshawk surveys on the Beartooth, Ashland, and Sioux Districts of the Custer-Gallatin National Forest: 2012-2014. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 114pp.

Maxell, B.A. 2016. Northern Goshawk surveys on the Beartooth, Ashland, and Sioux Districts of the Custer-Gallatin National Forest: 2012-2014. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 114pp. McGee, M., D.A. Keinath and G.P. Beauvais. 2002. Survey for rare vertebrates in the Pinedale Field Office of the USDI Bureau of Land Management (Wyoming). Unpublished report prepared for USDI Bureau of Land Management. Wyoming State Office by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database. University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming.

McGee, M., D.A. Keinath and G.P. Beauvais. 2002. Survey for rare vertebrates in the Pinedale Field Office of the USDI Bureau of Land Management (Wyoming). Unpublished report prepared for USDI Bureau of Land Management. Wyoming State Office by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database. University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming. Montana Bat Working Group. 2020. Recommendations to reduce bat fatalities at wind energy facilities in Montana. Presented to the Montana Fish and Wildlife Commission.

Montana Bat Working Group. 2020. Recommendations to reduce bat fatalities at wind energy facilities in Montana. Presented to the Montana Fish and Wildlife Commission. Montana Dept. of Fish, Wildlife and Parks. 2019. Final Project Report for Lick Creek and Old Dry Wolf Cave Bat Surveys 2016-2018. Helena, MT: Final Project Report. 32 pp.

Montana Dept. of Fish, Wildlife and Parks. 2019. Final Project Report for Lick Creek and Old Dry Wolf Cave Bat Surveys 2016-2018. Helena, MT: Final Project Report. 32 pp. Mumford, R. E. And J. B. Cope. 1964. Distribution and Status of the Chrioptera of Indiana. Am. Midl. Nat. 72(2):473-489.

Mumford, R. E. And J. B. Cope. 1964. Distribution and Status of the Chrioptera of Indiana. Am. Midl. Nat. 72(2):473-489. Musser, G.G. and S.D. Durrant. 1960. Notes on Myotis thysanodes in Utah. Journal of Mammalogy 41: 393-394.

Musser, G.G. and S.D. Durrant. 1960. Notes on Myotis thysanodes in Utah. Journal of Mammalogy 41: 393-394. Nagorsen, D.W., A.A. Bryant, D. Kerridge, G. Roberts, A. Roberts, and M.J. Sarell. 1993. Winter bat records for British Columbia. Northwestern Naturalist. 74(3): 61-66.

Nagorsen, D.W., A.A. Bryant, D. Kerridge, G. Roberts, A. Roberts, and M.J. Sarell. 1993. Winter bat records for British Columbia. Northwestern Naturalist. 74(3): 61-66. Natural Resources Conservation Service and Bat Conservation International. 1998. Bats and mines: Evaluating abandoned mines for bats: recommendations for survey and closure. 6 p.

Natural Resources Conservation Service and Bat Conservation International. 1998. Bats and mines: Evaluating abandoned mines for bats: recommendations for survey and closure. 6 p. Neuweiler, G. 1989. Foraging ecology and audition in echolocating bats. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 4(6): 160-166.

Neuweiler, G. 1989. Foraging ecology and audition in echolocating bats. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 4(6): 160-166. Neuweiler, G. 1990. Auditory adaptations for prey capture in echolocating bats. Physiological Reviews 70(3): 615-641.

Neuweiler, G. 1990. Auditory adaptations for prey capture in echolocating bats. Physiological Reviews 70(3): 615-641. Nowak, R.M. and E.P. Walker. 1994. Walker's bats of the world. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland.

Nowak, R.M. and E.P. Walker. 1994. Walker's bats of the world. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. O’Farrell, M.J., E.H. Studier, and W.G. Ewing. 1971. Energy utilization and water requirements of captive Myotis thysanodes and Myotis lucifugus (Chiroptera). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology 39(3): 549-552.

O’Farrell, M.J., E.H. Studier, and W.G. Ewing. 1971. Energy utilization and water requirements of captive Myotis thysanodes and Myotis lucifugus (Chiroptera). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology 39(3): 549-552. Ober, H.K. and J.P. Hayes. 2008. Prey Selection by Bats in Forests of Western Oregon. Journal of Mammalogy 89(5): 1191-1200.

Ober, H.K. and J.P. Hayes. 2008. Prey Selection by Bats in Forests of Western Oregon. Journal of Mammalogy 89(5): 1191-1200. Oechsli, L.M. 2000. Ex-urban development in the Rocky Mountain West: consequences for native vegetation, wildlife diversity, and land-use planning in Big Sky, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 73 p.

Oechsli, L.M. 2000. Ex-urban development in the Rocky Mountain West: consequences for native vegetation, wildlife diversity, and land-use planning in Big Sky, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 73 p. O'Farrell, M.J. And E.H. Studier. 1975. Population structure and emergence activity patterns in Myotis thysanodes and M. lucifugus (chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) in Northeastern New Mexico. The American Midland Naturalist 93(2):368-376.

O'Farrell, M.J. And E.H. Studier. 1975. Population structure and emergence activity patterns in Myotis thysanodes and M. lucifugus (chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) in Northeastern New Mexico. The American Midland Naturalist 93(2):368-376. O'Farrell, M.J., and E.H. Studier. 1973. Reproduction, growth, and development in Myotis thysanodes and M. Lucifugus (chiroptera: Vespertilionidae). Ecology 54:18-30.

O'Farrell, M.J., and E.H. Studier. 1973. Reproduction, growth, and development in Myotis thysanodes and M. Lucifugus (chiroptera: Vespertilionidae). Ecology 54:18-30. O'Farrell, Michael J. and Eugene H. Studier. 1980. Myoits thysanoides. American Society of Mammalogists, Lawrence, KS. Mammalian Species No. 137:1-5.

O'Farrell, Michael J. and Eugene H. Studier. 1980. Myoits thysanoides. American Society of Mammalogists, Lawrence, KS. Mammalian Species No. 137:1-5. Olson, C.R., D.P. Hobson, and M.J. Pybus. 2011. Changes in Population Size of Bats at a Hibernaculum in Alberta, Canada, in Relation to Cave Disturbance and Access Restrictions. Northwestern Naturalist 92(3): 224-230.

Olson, C.R., D.P. Hobson, and M.J. Pybus. 2011. Changes in Population Size of Bats at a Hibernaculum in Alberta, Canada, in Relation to Cave Disturbance and Access Restrictions. Northwestern Naturalist 92(3): 224-230. Peck, J. and A. Kuenzi. 2003. Relationship of Orientation on Internal Temperature of Artificial Bat Roosts, Southwestern Montana. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 9(1): 19-25.

Peck, J. and A. Kuenzi. 2003. Relationship of Orientation on Internal Temperature of Artificial Bat Roosts, Southwestern Montana. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 9(1): 19-25. Perkins, J. M., J. M. Barss, and J. Peterson. 1990. Winter records of bats in Oregon and Washington. Northwestern Naturalist 71:59-62.

Perkins, J. M., J. M. Barss, and J. Peterson. 1990. Winter records of bats in Oregon and Washington. Northwestern Naturalist 71:59-62. Priday, J., and B. Luce. 1997. Inventory of bats and bat habitat associated with caves and mines in Wyoming: completion report. Pp. 50-109 in Endangered and nongame bird and mammal investigations annual completion report. Nongame Program, Biological Services Section, Wyoming Game and Fish Department, Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Priday, J., and B. Luce. 1997. Inventory of bats and bat habitat associated with caves and mines in Wyoming: completion report. Pp. 50-109 in Endangered and nongame bird and mammal investigations annual completion report. Nongame Program, Biological Services Section, Wyoming Game and Fish Department, Cheyenne, Wyoming. Quay, W.B. 1948. Notes on Some Bats from Nebraska and Wyoming. Journal of Mammalogy 29(2): 181-182.

Quay, W.B. 1948. Notes on Some Bats from Nebraska and Wyoming. Journal of Mammalogy 29(2): 181-182. Rabe, M. J., T. E. Morrell, H. Green, J. C. demos, Jr., and C. R. Miller. 1998. Characteristics of ponderosa pine snag roosts used by reproductive bats in northeastern Arizona. Journal of Wildlife Management 62:612-621.

Rabe, M. J., T. E. Morrell, H. Green, J. C. demos, Jr., and C. R. Miller. 1998. Characteristics of ponderosa pine snag roosts used by reproductive bats in northeastern Arizona. Journal of Wildlife Management 62:612-621. Reid, F. 2006. Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America, 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston and New York, 608 pp.

Reid, F. 2006. Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America, 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston and New York, 608 pp. Rodhouse, T.J., P.C. Ormsbee, K.M. Irvine, L.A. Vierling, J.M. Szewczak, and K.T. Vierling. 2015. Establishing conservation baselines with dynamic distribution models for bat populations facing imminent decline. Diversity and Distributions 21(12): 1401-1413.

Rodhouse, T.J., P.C. Ormsbee, K.M. Irvine, L.A. Vierling, J.M. Szewczak, and K.T. Vierling. 2015. Establishing conservation baselines with dynamic distribution models for bat populations facing imminent decline. Diversity and Distributions 21(12): 1401-1413. Roemer, D.M. 1994. Results of field surveys for bats on the Kootenai National Forest and the Lolo National Forest of western Montana, 1993. Unpublished report for the Kootenai National Forest. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 19 pp.

Roemer, D.M. 1994. Results of field surveys for bats on the Kootenai National Forest and the Lolo National Forest of western Montana, 1993. Unpublished report for the Kootenai National Forest. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 19 pp. Rossillon, M. 1995. The McDonald Mine, west of Ravalli: a cultural resource inventory and evaluation. Renewable Technologies, Inc.. Butte. MT. Unpublished report. 24 pp.

Rossillon, M. 1995. The McDonald Mine, west of Ravalli: a cultural resource inventory and evaluation. Renewable Technologies, Inc.. Butte. MT. Unpublished report. 24 pp. Sasse, D. 1989. Lick Creek Cave - Survey for Bats. White Sulfur Springs, MT: USDA Forest Service, Lewis & Clark National Forest. Report to the district ranger of Kings Hill Ranger District.

Sasse, D. 1989. Lick Creek Cave - Survey for Bats. White Sulfur Springs, MT: USDA Forest Service, Lewis & Clark National Forest. Report to the district ranger of Kings Hill Ranger District. Sasse, D. C. 1991 . Survey of Tate-Potter Cave. Unpublished report, U.S. Forest Service Belt Creek Information Station, Neihart, MT. 1 3 pp.

Sasse, D. C. 1991 . Survey of Tate-Potter Cave. Unpublished report, U.S. Forest Service Belt Creek Information Station, Neihart, MT. 1 3 pp. Schmidly, D. J. 1991. The bats of Texas. Texas A and M University Press, College Station. 188 pp.

Schmidly, D. J. 1991. The bats of Texas. Texas A and M University Press, College Station. 188 pp. Schmidt, C.A. 2003. Conservation assessment for the fringed bat in the Black Hills National Forest, South Dakota and Wyoming. Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Black Hills NF, Custer, SD.

Schmidt, C.A. 2003. Conservation assessment for the fringed bat in the Black Hills National Forest, South Dakota and Wyoming. Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Black Hills NF, Custer, SD. Schmidt, U. and G. Joermann. 1986. The Influence of Acoustical Interferences on Echolocation in Bats. Mammalia 50(3): 379-390.

Schmidt, U. and G. Joermann. 1986. The Influence of Acoustical Interferences on Echolocation in Bats. Mammalia 50(3): 379-390. Schwab, N.A. 2004. Bat Conservation Strategy and plan for the State of Montana. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 10(1-4): 80.

Schwab, N.A. 2004. Bat Conservation Strategy and plan for the State of Montana. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 10(1-4): 80. Schwab, N.A., T.J. Mabee and R.J. Ritchie. 2012. An acoustic study of winter bat activity at three hibernacula, Montana, 2011. ABR Inc - Environmental Research and Services. Forest Grove, OR. 34pp.

Schwab, N.A., T.J. Mabee and R.J. Ritchie. 2012. An acoustic study of winter bat activity at three hibernacula, Montana, 2011. ABR Inc - Environmental Research and Services. Forest Grove, OR. 34pp. Schwab, Nathan. 2003. Mine Assessments for Bat Activity on Lands Managed by the BLM, Missoula Field Office 2003. Report to USDI BLM Missoula FO. Missoula, MT. 10pp.

Schwab, Nathan. 2003. Mine Assessments for Bat Activity on Lands Managed by the BLM, Missoula Field Office 2003. Report to USDI BLM Missoula FO. Missoula, MT. 10pp. Schwab, Nathan. 2004. Mine Assessment for Bat Activity on Lands Managed by the BLM, Missoula Field Office 2004. USDI BLM Missoula FO. Missoula, MT. 16 pp.

Schwab, Nathan. 2004. Mine Assessment for Bat Activity on Lands Managed by the BLM, Missoula Field Office 2004. USDI BLM Missoula FO. Missoula, MT. 16 pp. Sherwin, R.E., J.S. Altenbach, and D.L. Waldien. 2009. Managing abandoned mines for bats. Bat Conservation International.

Sherwin, R.E., J.S. Altenbach, and D.L. Waldien. 2009. Managing abandoned mines for bats. Bat Conservation International. Studier, E.H. 1968. Fringe-tailed bat in northeast New Mexico. The Southwestem Naturalist 13: 362.

Studier, E.H. 1968. Fringe-tailed bat in northeast New Mexico. The Southwestem Naturalist 13: 362. Studier, E.H. and M.J. O'Farrell. 1972. Biology of Myotis thysanodes and M. lucifugus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae)-I. Thermoregulation. Comparative Biochemistry Physiology Part A: Physiology. 41(3): 567-595.

Studier, E.H. and M.J. O'Farrell. 1972. Biology of Myotis thysanodes and M. lucifugus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae)-I. Thermoregulation. Comparative Biochemistry Physiology Part A: Physiology. 41(3): 567-595. Studier, E.H. and M.J. O'Farrell. 1976. Biology of Myotis thysanodes and M. lucifugus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae)—III. Metabolism, heart rate, breathing rate, evaporative water loss and general energetics. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology 54(4): 423-432.

Studier, E.H. and M.J. O'Farrell. 1976. Biology of Myotis thysanodes and M. lucifugus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae)—III. Metabolism, heart rate, breathing rate, evaporative water loss and general energetics. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology 54(4): 423-432. Studier, E.H., J.W. Procter, and D.J. Howell, May 20, 1970, Diurnal body weight loss and tolerance of weight loss in five species of Myotis. Journal of Mammalogy 51(2):302-309.

Studier, E.H., J.W. Procter, and D.J. Howell, May 20, 1970, Diurnal body weight loss and tolerance of weight loss in five species of Myotis. Journal of Mammalogy 51(2):302-309. Studier, E.H., V.L. Lysengen, and M.J. O’Farrell. 1975. Biology of Myotis thysanodes and M. lucifugus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) -- II. Bioenergetics of Pregnancy and Lactation. Comparative Biochemistry Physiology Part A: Physiology. 44(2): 467-471.

Studier, E.H., V.L. Lysengen, and M.J. O’Farrell. 1975. Biology of Myotis thysanodes and M. lucifugus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) -- II. Bioenergetics of Pregnancy and Lactation. Comparative Biochemistry Physiology Part A: Physiology. 44(2): 467-471. Swenson, J. E. and J. C. Bent. 1977. The bats of Yellowstone County, southcentral Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 37:82-84.

Swenson, J. E. and J. C. Bent. 1977. The bats of Yellowstone County, southcentral Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 37:82-84. Swenson, J.E. and G.F. Shanks, Jr. 1979. Noteworthy records of bats from northeastern Montana. Journal of Mammalogy. 60(3): 650-652

Swenson, J.E. and G.F. Shanks, Jr. 1979. Noteworthy records of bats from northeastern Montana. Journal of Mammalogy. 60(3): 650-652 Taylor, D.A.R. and M.D. Tuttle. 2007. Water for wildlife: a handbook for ranchers and range managers. Bat Conservation International. 20 p.

Taylor, D.A.R. and M.D. Tuttle. 2007. Water for wildlife: a handbook for ranchers and range managers. Bat Conservation International. 20 p. Thomas, D.W. 1995. Hibernating Bats Are Sensitive to Nontactile Human Disturbance. Journal of Mammalogy 76(3): 940-946.

Thomas, D.W. 1995. Hibernating Bats Are Sensitive to Nontactile Human Disturbance. Journal of Mammalogy 76(3): 940-946. Tigner, J. and E.D. Stukel. 2003. Bats of the Black Hills: a description of status and conservation needs. South Dakota Department of Game, Fish, and Parks. Wildlife Division Report 2003-05. 94 p.

Tigner, J. and E.D. Stukel. 2003. Bats of the Black Hills: a description of status and conservation needs. South Dakota Department of Game, Fish, and Parks. Wildlife Division Report 2003-05. 94 p. Tigner, Joel. 2005. Active Season Bat Surveys of Select Abandoned Mines in the Thompson River Valley, Sanders County, MT. BATWORKS, Rapid City, SD. 16pp.