View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Water Howellia - Howellia aquatilis

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Howellia aquatilis is endemic to the Pacific Northwest where Montana is home to the largest number of occupied wetlands. Yet, the total occupied area is small and clustered in one narrow river valley in western Montana, making this plant vulnerable to actions that impact its restricted habitat, specific water requirements, or interrupt its annual life cycle. Howellia aquatilis is restricted to depressional wetlands and old river oxbows in the Swan Valley, where it occupies small vernal ponds within glacial kettles in the valley floor. Plants depend upon a hydrologic cycle whereby water in the ponds rise after snowmelt and spring rains, then partially recedes, or completely evaporates by late summer. Based on available monitoring data, populations appear to be stable and persisting (Pipp 2016; Pipp 2017). Potential threats are recognized and remain conceivable, but negative impacts have been minimized through federal land acquisitions and management direction adopted by the Flathead National Forest in its Water Howellia Conservation Strategy (USFS 1997). In 2021, the US Fish & Wildlife Service removed Howellia aquatilis from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Plants (USFWS 2021) and implemented a Post-Delisting Monitoring Plan (USFWS 2020). The 2022 state status review retains Howellia aquatilis as a Species of Concern in Montana.

- Details on Status Ranking and Review

Range Extent

ScoreC - 250-1,000 sq km (~100-400 sq mi)

CommentThe 221 Species Occurrences (SOs) occur within a range extent of 496 square kilometers.

Area of Occupancy

ScoreE - 26-125 4-km2 grid cells

CommentOf the 30,590 4x4 square kilometer grid cells that cover Montana, 29 cells are occupied by Howellia aquatilis Species Occurrences.

Number of Populations

ScoreD - 81 - 300

Comment221 Species Occurrences found from 1978 to 2018.

Number of Occurrences or Percent Area with Good Viability / Ecological Integrity

ScoreE - Many (41-125) occurrences with excellent or good viability or ecological integrity

Comment80 Species Occurrences were given an A, AB, or B rank in 2009.

Threats

ScoreBC - High - Medium

CommentReported threats to Montana's populations of Water Howellia include those that impact its restricted habitat, specific water requirements, or interrupt its annual life cycle (MTNHP Threat Assessment 2021). These include the potential for negative impacts to ground or water quality from residential development, pond construction, wood harvesting, temporary road construction, and road maintenance activities, in addition to habitat invasion from aggressive exotic wetland plants.

General Description

PLANTS: A glabrous, much-branched, aquatic winter annual. Stems are slender, fragile, and up to 100 cm long. Branching can begin several inches above its the base. Stems ultimately grow toward the surface of the water. Stems that sever from the rooted base can persist and freely float through the field season. Sources: Hitchcock et al. 1959, Shelly and Moseley 1988.

LEAVES: The simple, alternate, or occasionally opposite or whorled (in threes) stem leaves are narrowly linear, 1-5 cm long by 1.5mm wide, and entire-margined. Sources: Hitchcock et al. 1959, Shelly and Moseley 1988; USFWS 1996.

INFLORESCENCE: Beneath the surface of the water are small cleistagamous (non-opening) flowers that lack petals and are solitary in the leaf axils. Once stems reach the surface, small, chasmagamous (opening), white-petaled flowers emerge in a narrow, terminal, leafy-bracted raceme inflorescence. Corollas are irregular and 2-3 mm long. Both flower types give rise to thin-walled fruits (capsules) which form below the attachment of the petals. Fruits 5-13 mm long and contain elongated seeds that are 2-4 mm long. Sources: Hitchcock et al. 1959, Shelly and Moseley 1988; USFWS 1996.

The genus Howellia is named for Thomas and Joseph Howell, two botanists who first collected the plant in 1879 (USFS 1997). Later in 1879, botanist Asa Gray determined that the plant represented both a new genus and species and published its description (Gray 1879).

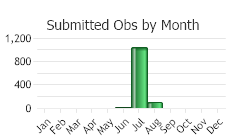

Phenology

Plants are visible under the water’s surface in early summer. Submerged (underwater) flowers form on stems in June. Emergent flowers have petals and bloom around mid-July. Flowering continues into summer as ponds draw down. Underwater and emergent flowers produce fruits beginning in mid-summer. In late summer to early autumn when pond waters have completely receded, decomposing stems can be seen on the exposed mucky surface of pond bottoms. Seedlings are tiny and difficult to find but can be seen after the first frosts or periods of widely fluctuating temperatures (Mantas 2022, personal communication).

Diagnostic Characteristics

Howellia is a monotypic genus with no close relatives. Water starwort and Water Howellia are often seen growing together.

Water Howellia –

Howellia aquatilis*Member of Family Campanulaceae.

*Submerged leaves are typically alternate but sometimes whorled (in threes).

*Submerged, floating, and emergent leaves are linear.

*Flowers at or above the water's surface are tiny with conspicuous white petals.

*Fruits are linear capsules, 5-13 mm long.

*Aquatic plants.

Water Starwort –

Callitriche heterophylla*Member of Family Callitrichaceae.

*Submerged leaves are linear and usually opposite (only rarely whorled).

*Floating leaves are ovate.

*Flowers are green, inconspicuous due to the lack of a corolla, and submerged.

*Fruits are heart shaped.

*Aquatic plants.

White Water Buttercup -

Ranunculus aquatilis*Member of Family Ranunuculaceae.

*Submerged leaves float, are kidney-shaped (reniform) in outline, and twice divided into thread-like segments.

*Flowers are white, symmetrically 5-petaled, and sit on top of the water. From a distance the flowers look like Water Howellia until you get closer to see the differences.

*Aquatic plants.

Great Basin Downingia –

Downingia laeta, SOC

*Member of Family Campanulaceae.

*Submerged leaves are lance-shaped, usually alternate, and whither early.

*Emergent leaves are lance-shaped, usually alternate, and sessile on the stem. Floating leaves absent.

*Flowers are light blue to purplish and marked with white or yellow, and only emergent.

*Fruits are capsules 20-45 mm long.

*Plants grow in shallow water and drying mud of pond/lake margins in the valleys and plains.

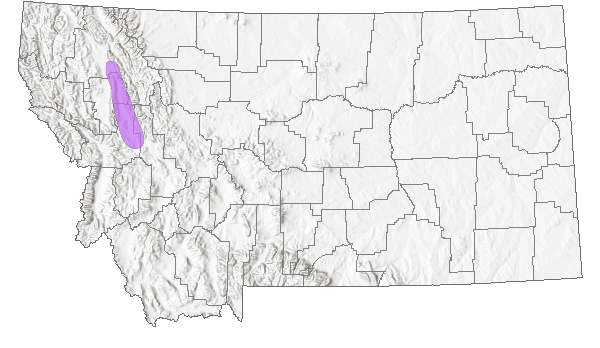

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

Howellia aquatilis is endemic to the Pacific Northwest. Extant populations are known from a limited number of counties in northern California, northwestern Oregon, western Washington, eastern Washington, northern Idaho, and western Montana (USFWS 2021).

Water Howellia was first collected in May of 1879 from a slough on the Sauvies Island along the Columbia River in Multnomah County, Oregon (USFS 1997; USFWS 2019).

In Montana, Water Howellia was first collected in Missoula County in 1978 by a student in the botany department at the University of Montana (https://www.pnwherbaria.org; USFS 1997). Water Howellia is restricted to glacial depressions in the Swan Valley.

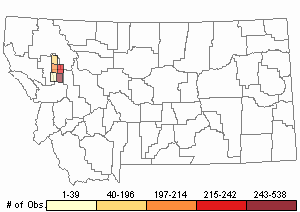

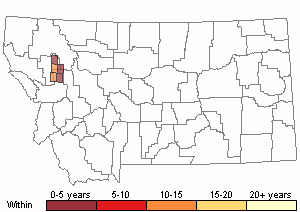

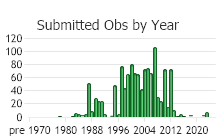

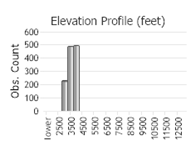

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 1328

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

In Montana, Water Howellia is restricted to glacial depressions in the Swan Valley.

Plants are aquatic, growing in small, often less than one acre,

vernal ponds that fill from snowmelt and rain in the spring and partially or completely dry up by late summer into autumn. Pond substrates usually consist of a thin layer of organic sediments underlain by consolidated glacial silts and clays. In the Swan Valley, ponds with Water Howellia occur in glacial kettles, though one occurrence exists in an oxbow slough of the Swan River. Although the slough is not a depressional glacial feature, it does exhibit the same seasonal draw down of water.

Water Howellia can also root in the shallow water at the edges of deeper ponds (Lesica et al. 1988; USFWS 1996).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Wetland and Riparian

Alkaline - Saline Wetlands

Alpine Riparian and Wetland

Riparian and Wetland Forest

Wet Meadow and Marsh

Open Water

Open Water

Ecology

ASSOCIATED SPECIES

Vegetation within individual wetlands is commonly dominated by Carex vesicaria, Typha latifolia, Equisetum fluviatile, Eleocharis palustris, and/or Sium suave. Ponds exist in a coniferous forest matrix of various age classes. Pond margins are dominated by Populus balsamifera and Salix bebbiana with a smaller component of Populus tremuloides (Mincemoyer 2005).

PLANT GENETICS

Across Water Howellia’s geographic range, there is little genetic variation within as well as between populations. Possible reasons for this low variation are: 1) cleistogamy, which can cause inbreeding, 2) lack of time since populations diverged, and 3) gene flow between populations. Lesica et al. (1988) proposed that the low genetic diversity was due to a lack of time for evolutionary development and/or cleistogamy. However, Schierenbeck and Phipps (2010) found genetic dissimilarities between the Washington-Idaho populations as compared to those in Montana and California, which negates that lack of time for evolutionary development and would explain the low diversity. They proposed that gene flow between the California and Montana populations is the reason for lower genetic diversity between populations as opposed to within populations. They go further to propose that this gene flow is attributed to bird dispersal, based on documented waterfowl migration routes across the Pacific Northwest between Medicino County, California and Lake County, Montana (Schierenbeck and Phipps 2010).

VERNAL POND HYDROLOGY

The water source and mechanisms controlling the hydrology of Water Howellia occupied ponds in the Swan Valley was studied (Reeves and Woessner 2004; Reeves 2001) . Physical and hydrological properties of the wetland sediment and watershed till matrix control the amount and rate of water recharge, as well as the rate and quantity of groundwater-surface water exchange in these vernal ponds. The interactions between surface water and ground water are complex in these wetland systems. The study developed a wetland water balance based on conditions found in 1999 and 2000. Plant transpiration, ground water inflow, and when present, surface water outflow are the major hydrological controls from spring through early autumn. From April to early May, snow melt fills the ponds from overland flow and recharges the surrounding watershed. From mid-June to mid-August input from precipitation decreases while ground water inflow from surrounding sediments in the micro-basin mitigates the water lost from direct evaporation and plant transpiration. From late August through early September, the water table drops below the wetland creating a gradient that favors leakage and eliminates inflow to the wetland. In late autumn, decreased plant transpiration, cooler temperatures, and an increase in precipitation cause surrounding water tables to recharge and ponds to fill again. In winter, snow accumulation primes the micro-basin for the next annual cycle.

The water chemistry of the surface water is similar to that found in the shallow ground water which is predominantly calcium bicarbonate (Reeves and Woessner 2004). Lesser concentrations of potassium, magnesium, manganese, sodium, and fluoride are also present. The pH and specific conductance are seasonally variable. The pH values ranged from 5.62 to 7.97.

The study modelled how natural and anthropogenic modification of the wetland watershed may alter wetland hydrology (Reeves and Woessner 2004). The model found that an increase in the yield of micro-basin water may occur when trees are removed by harvesting or a stand replacing fire. This is primarily due to the loss of plant transpiration. The increase in water yield usually lasts a few years, depending upon the qualities of the re-colonizing vegetation.

Reproductive Characteristics

Plants reproduce by seed.

FLOWERS

Water Howellia produces two distinctly different types of flowers (Shelly 1988; Mincemoyer 2005). Under the water’s surface, cleistagamous flowers (flowers that never open and lack a conspicuous corolla) form in the axils of branches as plants grow toward the water’s surface. Once stems reach the surface, white-petaled chasmagamous flowers (those that open) form in the axils of branches on or just above the water’s surface. These flowers are scattered, with or without pedicles, and are about 2-2.7 mm long. The white-petaled corollas are irregular, with deeply cleft tubes that are five-lobed. The filaments and anthers are connate with two of the anthers shorter than the others. The calyx lobes are 1.5-7 mm long with stout pedicels that are 1-4 (8) mm long, merging gradually with the base of the capsule. The ovary is unilocular, with parietal placentation. Stigma is 2-lobed.

Studies have found that self-pollination appears to be the common means of fertilization and that out-crossing, though possible, is probably extremely rare (Lesica et al. 1988; Shelly and Moseley 1988).

FRUITS

The fruit is a capsule that is 5-13 mm long, 1-2 mm thick, and irregularly dehiscent by the rupture of the very thin lateral walls. Seeds are 5 or fewer, relatively large, 2-4 mm long, and shiny brown.

LIFE CYCLE

Water howellia is a winter annual. Seedlings germinate in fall and overwinter under snow. In early spring, ponds fill with water from snow melt, rain, and rising groundwater. Seedlings grow into mature plants through spring and early summer. The submerged cleistogamous flowers (flowers that do not open and are self-pollinated) reach anthesis in late June. Chasmogamous flowers (flowers that open and allow for cross-pollination) bloom at the surface in mid-July though the end of the growing season. Seed dispersal starts in June from submerged flowers and extends until late summer from emergent flowers (USFWS 1996). Though spread of seeds between ponds by waterfowl or other animals may be possible, it has not been documented (Mincemoyer 2005; Schierenbeck and Phipps 2010). Plants die when the pond water completely evaporates. Mature seeds that have settled in pond sediments during the growing season germinate only after being exposed to air and fluctuating temperatures in the autumn, which breaks seed dormancy (Lesica et al. 1988; Lesica 1990).

Population size in a given year is affected by the extent to which the pond dried out at the end of the previous year. Due in part to this dependence, population size varies widely from year to year. Exceedingly wet years will detrimentally affect population size in the following year as seeds will not germinate under water.

Long-term seed viability is uncertain, though Lesica (1992) has shown that seeds lying in the soil longer than eight months have decreased rates of germination and vigor. However, annual monitoring of Montana populations has shown populations to rebound after two consecutive years where no plants were observed. This provides some evidence that a significant number of seeds remain viable for at least three years, providing a buffer against unfavorable growing conditions in consecutive years.

Management

ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT

Recognizing that America's rich natural heritage is of esthetic, ecological, educational, recreational, and scientific values to our Nation and its people, the Endangered Species Act (ESA) was created to recover and protect imperiled species. The ESA of 1973 as amended by Congress provides for the conservation of endangered and threatened species of fish, wildlife, and plants, and for other purposes. The ESA mostly requires the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to: a) list, classify, protect, and recover species [Sections 4, 9, and 12], b) review and evaluate federal actions for potential affects to listed species [Section 7], c) oversee recovery activities [Sections 4, 5, and 6]; d) work cooperatively with the States [Section 6] and internationally [Section 8]; and e) provide exemptions (permits) for scientific efforts and conservation activities [Section 10]. The USFWS uses five main factors to determine if a proposed species warrants listing under the ESA: present or threatened habitat/range loss, overutilization, disease/predation, inadequacy of protections, and other threats. The de-listing of a species is assessed using three criteria: recovery, extinction, or erroneous information at the time of listing.

Water Howellia under the ESA

Water Howellia was listed as Threatened under the ESA on July 14, 1994 (59 FR 35860; USFWS 1994). Designated by the USFWS, Threatened Species are "any species which is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range.

Water Howellia was listed because of potential and already occurring impacts from introduced plant species (Phalaris arundinacea and Lythrum salicaria), timber harvests, grazing, and development as well as its low genetic variation, extremely specialized habitat, threats from climatic change, and threats from natural wetland succession. It was also found that existing regulatory mechanisms were inadequate for its protection, especially for occurrences outside of federal lands (USFWS 1994). At the time of the listing, there were 107 documented occurrences across it range which included California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana. Washington, Montana, and Idaho had about 48, 59, and 1 extant site(s), while sites in California, Oregon, and some in Idaho and Washington were thought to have been extirpated.

In 1996 a draft recovery plan was prepared by the Natural Heritage Programs for Montana and Washington for the USFWS in Helena, Montana (Shelly and Gamon 1996). The recovery plan focused on implementing management plans for Howellia populations on federally-managed lands, conducting research on the life history and management of the species, and encouraging conservation practices on state and private lands (Shelly and Gamon 1996). A final recovery plan was never issued.

In 2005 the Range-wide Status Assessment of Water Howellia was prepared by the Montana Natural Heritage Program for the USFWS (Mincemoyer 2005). In 2013 the USFWS published a Five-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation that re-assessed current population levels, threats, genetics, and other factors (USFWS 2013). This Five-Year Review concluded that by 2012 302 extant Water Howellia occurrences were known. Across its range 91% of the occurrences are found in three meta-populations that represent three distinct geographical regions: Swan Valley of western Montana, Department of Defense property in western Washington, and Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge in eastern Washington. In addition, inventories re-located or newly found sites in Idaho, Oregon, California, and some other places in Washington. The Service concluded that Water Howellia was more common and widespread and less threatened than originally suspected due to changes in management practices and inventories, and that listing under the ESA is no longer warranted (USFWS 2013). In anticipation that Water Howellia could be de-listed, the USFWS in collaboration with state and federal stakeholders from throughout its range prepared a draft Post-Delisting Monitoring Plan in 2017.

The USFWS proposed to remove Water Howellia from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Plants on October 7, 2019 (84 FR 53380; USFWS 2019). The agency's recommendation was based on the best available scientific and commercial data [monitoring data] which found that federal management plans have been effective at maintaining a minimum number of occurrences and reducing or eliminating anthropogenic threats. By 2017, 307 extant Water Howellia occurrences across its range had been documented. This proposed action triggered a public comment period on both the proposed action to remove and the draft Post-Delisting Monitoring Plan (USFWS 2017).

The USFWS issued the final rule to remove Water Howellia from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Plants on June 16, 2021 (86 FR 31955; USFWS 2021). A thorough review found since the time of listing in 1994, the threats are not as significant and/or have been sufficiently minimized and that the species' populations and distribution are much greater than previously thought. As a result, Water Howellia no longer meets the definition of an endangered or threatened species under ESA of 1973, as amended.

Post De-listing Monitoring Plan

Removal from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Plants in 2021 (86 FR 31955) triggered the use of Section 4(g)(1) of the ESA of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq.), which requires the USFWS to work cooperatively with the States to implement a monitoring program for not less than five years. The intent of a post de-listing monitoring is to validate delisting assumptions and verify that the species is self-sustaining without the protections afforded under the ESA (16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq.).

The Water Howellia Post-Delisting Monitoring Plan (PDM) was finalized in 2020 and approved on January 12, 2021 (USFWS 2020). The PDM goal is to monitor a minimum of 60 of the 307 known Water Howellia occurrences across its range; whereby, at least 30 occurrences in the states of Montana and Washington are monitored. Further, monitoring is to occur for two consecutive years at three distinct time intervals over a 15-year period. The rationale being that plants do not emerge each year because its annual life cycle is tied to cycles in climate and hydrology. After completing six years of monitoring over the 15-year PDM period, all years of data from the three metapopulations and other occurrences are to be analyzed for trends and factors that may influence population trend, such as drought, and a determination on its status is to be issued (USFWS 2020).

CONSERVATION STRATEGY

Probably the most significant management document is the Conservation Strategy for Howellia aquatilis developed by the U.S. Forest Service, Region 1 and the Flathead National Forest (USFS 1997). This document identifies the conservation strategies that are needed to ensure the long-term viability of Water Howellia on U.S. Forest Service lands in Montana (USFS 1997). Recommendations in the strategy have led to significant management tactics that have aided its persistence, including but not limited to:

* Coordination and development of an interagency technical working group that facilitated inventories, monitoring, and research during the 1990s and early 2000s.

* Concept to manage for both occupied and unoccupied Water Howellia habitat. Ponds that appear to have habitat, but for which surveys have not detected Water Howellia plants are deemed 'unoccupied' habitat.

* Concept that a minimum 300-foot buffer around pond margins should be retained or managed to maintain a favorable physical environment in and around ponds

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

STATE THREAT SCORE REASON

Reported threats to Montana's populations of Water Howellia include those that impact its restricted habitat, specific water requirements, or annual life cycle (MTNHP Threat Assessment 2021). Its annual life cycle must sync with precipitation patterns that fill ponds in the spring and at least partially dry by autumn. An overall State Threat Score of "high to medium" is assigned to Water Howellia because the individual reported threat categories resulted in two medium and two low scores (Master et al. 2012; MTNHP Threat Assessment 2021), as follows:

Residential and Commercial Development

Water and land resource development on private lands that surround Water Howellia occurrences has been reported as a potential threat. Prior to 2010, Plum Creek Timber Company owned many land parcels with ponds both occupied and unoccupied (but representing potential habitat) by Water Howellia (Pipp 2017). By 2010, a land acquisition transferred land ownership from Plum Creek to The Nature Conservancy. Two years later these parcels were transferred to the Flathead National Forest, Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation, and Montana Fish, Wildlife, & Parks. About 67,000 acres of private land were transferred to federal ownership (Federal Register 2019). Based on analysis conducted from 2015-2016, 43 Water Howellia occurrences (20% of all Water Howellia occurrences) are surrounded by some amount of private land (Pipp 2016). The 2021 MTNHP Threat Assessment calculated a low threat impact score from 'residential & commercial development' [on-going timing, restricted scope, and slight to moderate severity].

Wood Harvesting

Wood harvesting operations have long been recognized as a potential threat to Water Howellia because activities could directly or indirectly alter pond hydrology levels, water quality, water temperature, and/or surrounding vegetation (MTNHP Threat Assessment 2021; Pipp 2017). Based on analysis conducted from 2015-2016, almost 86% of Water Howellia ponds are surrounded entirely or partially by the Flathead National Forest and Swan River State Forest (Pipp 2016). The persistence of Water Howellia at 220 occurrences (ponds) was evaluated relative to wood harvesting (stand treatments) within a 300-foot buffer around these pond margins from 1978 to 2014. In this timeframe, 127 ponds had at least 1 stand treatment take place within a portion of their 300-foot buffers (treated buffers) while 93 ponds lacked stand treatments within their buffers (untreated buffers) (Pipp 2017). During this timeframe, Water Howelia was found 83% (632 positive/762 total observations) of the time in ponds with treated buffers and 86% (553 positive/645 total observations) of the time with untreated buffers (Pipp 2017). The difference was statistically significant (Pipp 2017). This result is an indication that the existing stand treatments within buffer may have had little influence on the presence/absence of Water Howellia. The report concluded that while timber prescriptions have occurred within pond buffers, best management practices, conservation strategy guidelines (USFS 1997), and other management tools appear to have minimized negative impacts to water quality or populations on the Flathead National Forest since the mid-1990s. The 2021 MTNHP Threat Assessment calculated a low to medium threat impact score from 'logging and wood harvesting' [on-going timing, large scope, and slight to moderate severity].

Hydrologic Alterations

Pond construction at privately owned locations has been reported as a potential threat. Hydrologic changes, such as damming or diversion of water, can injure or destroy existing Water Howellia populations. Drafting water by a County weed crew has been reported as a threat at one Water Howellia occurrence; however, the impact is unknown. The 2021 MTNHP Threat Assessment calculated a low threat impact score from 'Dams and Water Management/Use' [on-going timing, small to restricted scope, and slight to moderate severity].

Non-Native Plant Invasion

Reed Canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea) is reported as a direct threat to Water Howellia. Reed Canarygrass is known to rapidly invade, and eventually replace native plants in similar habitats. It is suspected that Montana has populations of native and cultivar strains of Reed Canarygrass (Merigliano and Lesica 1998). It is speculated that cultivars may be the invasive plants. Monitoring studies conducted from 1998-2012 in the Swan Valley found that Reed Canarygrass was present at 123 Water Howellia occurrences; however, the analysis found no detectable trend in abundance or distribution for either species (Pipp 2016).

Temporary road construction and associated equipment has been reported as a vector for weed encroachment that could potentially impact, at some point, all Water Howellia occurrences on USFS lands.

The 2021 MTNHP Threat Assessment calculated a low to medium threat impact score from 'invasive species' [on-going timing, large scope, and slight to moderate severity].

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria (CPNWH) Specimen Database. No Date. Plant specimen data displayed on the PNW Herbaria portal. Website http://www.pnwherbaria.org.

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria (CPNWH) Specimen Database. No Date. Plant specimen data displayed on the PNW Herbaria portal. Website http://www.pnwherbaria.org. Gray, Asa. 1879. Proc. Am. Acad. 15:43-44.

Gray, Asa. 1879. Proc. Am. Acad. 15:43-44. Hitchcock, C.L., A. Cronquist, M. Ownbey and J.W. Thompson. 1959. Vascular plants of the Pacific Northwest, Part 4. Ericaceae through Campanulaceae. Seattle, WA and London, UK: University of Washington Press. 510 p.

Hitchcock, C.L., A. Cronquist, M. Ownbey and J.W. Thompson. 1959. Vascular plants of the Pacific Northwest, Part 4. Ericaceae through Campanulaceae. Seattle, WA and London, UK: University of Washington Press. 510 p. Lesica, P. 1990. Habitat requirements, germination behavior and seed bank dynamics of Howellia aquatilis in the Swan Valley, Montana. Unpublished report to the Flathead National Forest. Conservation Biology Research, Helena, Montana. 44 pp. plus appendix.

Lesica, P. 1990. Habitat requirements, germination behavior and seed bank dynamics of Howellia aquatilis in the Swan Valley, Montana. Unpublished report to the Flathead National Forest. Conservation Biology Research, Helena, Montana. 44 pp. plus appendix. Lesica, P. 1992. Autecology of the endangered plant Howellia aquatilis: Implications for management and reserve design. Ecological Applications 2(4):411-421.

Lesica, P. 1992. Autecology of the endangered plant Howellia aquatilis: Implications for management and reserve design. Ecological Applications 2(4):411-421. Lesica, P., R.F. Leary, F.W. Allendorf, and D.E. Bilderback. 1988. Lack of genetic diversity within and among populations of an endangered plant, Howellia aquatilis. Conservation Biology 2: 275-282.

Lesica, P., R.F. Leary, F.W. Allendorf, and D.E. Bilderback. 1988. Lack of genetic diversity within and among populations of an endangered plant, Howellia aquatilis. Conservation Biology 2: 275-282. Mantas, M. 2022. Personal communication re: observations of Howellia aquatilis on the Flathead National Forest. Former Forest Botanist, Flathead National Forest, Kalispell, MT.

Mantas, M. 2022. Personal communication re: observations of Howellia aquatilis on the Flathead National Forest. Former Forest Botanist, Flathead National Forest, Kalispell, MT. Master, L.L, D. Faber-Langendoen, R. Bittman, G.A. Hammerson, B. Heidel, L. Ramsay, K. Snow, A. Teucher, and A. Tomaino. 2012. NatureServe Conservation Status Assessments: Factors for Evaluating Species and Ecosystem Risk. Arlington, VA: NatureServe. 64 p.

Master, L.L, D. Faber-Langendoen, R. Bittman, G.A. Hammerson, B. Heidel, L. Ramsay, K. Snow, A. Teucher, and A. Tomaino. 2012. NatureServe Conservation Status Assessments: Factors for Evaluating Species and Ecosystem Risk. Arlington, VA: NatureServe. 64 p. Merigliano, M.F. and P. Lesica. 1998. The native status of reed canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea L.) in the inland Northwest, U.S.A. Natural Areas Journal, 18: 223-230.

Merigliano, M.F. and P. Lesica. 1998. The native status of reed canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea L.) in the inland Northwest, U.S.A. Natural Areas Journal, 18: 223-230. Mincemoyer, S. 2005. Range-wide status assessment of Howellia aquatilis (water howellia). Prepared for the U.S.F.W.S. Helena, MT: Montana Natural Heritage Program. 21 p. + appendices.

Mincemoyer, S. 2005. Range-wide status assessment of Howellia aquatilis (water howellia). Prepared for the U.S.F.W.S. Helena, MT: Montana Natural Heritage Program. 21 p. + appendices. MTNHP Threat Assessment. 2021. State Threat Score Assignment and Assessment of Reported Threats from 2006 to 2021 for State-listed Vascular Plants. Botany Program, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana.

MTNHP Threat Assessment. 2021. State Threat Score Assignment and Assessment of Reported Threats from 2006 to 2021 for State-listed Vascular Plants. Botany Program, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana. Pipp, A. 2016. 1978-2016 data compilation and analysis for Howellia aquatilis in Montana. Information from 2015 to 2016 provided in datasheet, tabular, graphical, and summarized formats. Program Botanist, MTNHP, Helena, Montana.

Pipp, A. 2016. 1978-2016 data compilation and analysis for Howellia aquatilis in Montana. Information from 2015 to 2016 provided in datasheet, tabular, graphical, and summarized formats. Program Botanist, MTNHP, Helena, Montana. Pipp, A. 2017. An analysis of disturbance in buffers surrounding occupied Water Howellia (Howellia aquatilis) ponds and unoccupied ponds in Montana. Prepared for the USFWS, MT Ecological Services Field Office, Helena, MT. Prepared by the MTNHP, Helena, Montana. 19 p. + appendix.

Pipp, A. 2017. An analysis of disturbance in buffers surrounding occupied Water Howellia (Howellia aquatilis) ponds and unoccupied ponds in Montana. Prepared for the USFWS, MT Ecological Services Field Office, Helena, MT. Prepared by the MTNHP, Helena, Montana. 19 p. + appendix. Reeves, D.M. 2001. Hydrologic controls on the survival of water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) and implications of land management, Swan Valley, MT. M.Sc. Thesis. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 222 p.

Reeves, D.M. 2001. Hydrologic controls on the survival of water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) and implications of land management, Swan Valley, MT. M.Sc. Thesis. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 222 p. Reeves, D.M. and W.W. Woessner. 2004. Hydrologic controls on the survival of water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) and implications of land management. Journal of Hydrology 287:1-18.

Reeves, D.M. and W.W. Woessner. 2004. Hydrologic controls on the survival of water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) and implications of land management. Journal of Hydrology 287:1-18. Schierenbeck, K.A. and F. Phipps. 2010. Population genetics of Howellia aquatilis (Campanulaceae) in disjunct locations throughout the Pacific Northwest. Genetica 138:1161-1169.

Schierenbeck, K.A. and F. Phipps. 2010. Population genetics of Howellia aquatilis (Campanulaceae) in disjunct locations throughout the Pacific Northwest. Genetica 138:1161-1169. Shelly, J.S. 1988. Status review of Howellia aquatilis, U.S. Forest Service, Region 1, Flathead National Forest. Montana Natural Heritage Program report to U.S. Forest Service.120 p.

Shelly, J.S. 1988. Status review of Howellia aquatilis, U.S. Forest Service, Region 1, Flathead National Forest. Montana Natural Heritage Program report to U.S. Forest Service.120 p. Shelly, J.S. and J. Gamon. 1996. Howellia aquatilis (Water Howellia) recovery plan [Technical draft]. Unpublished report to the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 58 p.

Shelly, J.S. and J. Gamon. 1996. Howellia aquatilis (Water Howellia) recovery plan [Technical draft]. Unpublished report to the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 58 p. Shelly, J.S. and R. Moseley. 1988. Report on the conservation status of Howellia aquatilis, a candidate threatened species. Helena, MT: MTNHP, unpublished report to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Denver. 166 p.

Shelly, J.S. and R. Moseley. 1988. Report on the conservation status of Howellia aquatilis, a candidate threatened species. Helena, MT: MTNHP, unpublished report to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Denver. 166 p. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1973. Endangered species act of 1973 as amended through the 108th Congress. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, USFWS. 41 p.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1973. Endangered species act of 1973 as amended through the 108th Congress. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, USFWS. 41 p. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Endangered and Threatened wildlife and plants; the plant, Water howellia (Howellia aquatilis), determined to be a Threatened species. 50 CFR Part 17. Federal Register 59(134):35860-35864.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Endangered and Threatened wildlife and plants; the plant, Water howellia (Howellia aquatilis), determined to be a Threatened species. 50 CFR Part 17. Federal Register 59(134):35860-35864. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1996. Biological opinion on Amendment 20 to the Flathead National Forest plan. Helena, MT: Montana Field Office. 13 p.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1996. Biological opinion on Amendment 20 to the Flathead National Forest plan. Helena, MT: Montana Field Office. 13 p. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2013. Water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) 5-year review: summary and evaluation. Helena, MT: MT Ecological Services Field Office. 39 p.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2013. Water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) 5-year review: summary and evaluation. Helena, MT: MT Ecological Services Field Office. 39 p. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2019. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; removal of Howellia aquatilis (water howellia) from the list of endangered and threatened plants. Federal Register 84(194):53380-53397.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2019. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; removal of Howellia aquatilis (water howellia) from the list of endangered and threatened plants. Federal Register 84(194):53380-53397. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2021. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; removing the water howellia from the list of endangered and threatened plants. Federal Register 86(114):31955-31972.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2021. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; removing the water howellia from the list of endangered and threatened plants. Federal Register 86(114):31955-31972. U.S. Fish and Wildlife. 2020. Post-delisting monitoring plan for water howellia (Howellia aquatilis). Helena, MT: MT Ecological Services Field Office. 33 p.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife. 2020. Post-delisting monitoring plan for water howellia (Howellia aquatilis). Helena, MT: MT Ecological Services Field Office. 33 p. U.S. Forest Service. 1997. Conservation strategy, Howellia aquatilis, Flathead National Forest (second edition). Missoula, MT: J. Stephen Shelly, USDA Forest Service, Northern Region. 24 p.

U.S. Forest Service. 1997. Conservation strategy, Howellia aquatilis, Flathead National Forest (second edition). Missoula, MT: J. Stephen Shelly, USDA Forest Service, Northern Region. 24 p.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Brunsfeld, S.J. and C.T. Baldwin. 1998. Howellia aquatilis genetics: not so boring after all. In: Forum on Research and Management of Howellia aquatilis. Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, Cheney, WA. March 24-25.

Brunsfeld, S.J. and C.T. Baldwin. 1998. Howellia aquatilis genetics: not so boring after all. In: Forum on Research and Management of Howellia aquatilis. Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, Cheney, WA. March 24-25. Bursick, R.J. 1995. Update: report on the conservation status of Howellia aquatilis in Idaho. Unpublished report. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Boise. 8 p.

Bursick, R.J. 1995. Update: report on the conservation status of Howellia aquatilis in Idaho. Unpublished report. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Boise. 8 p. Clegg, M. and A. Lombardi. 2000. Status report for water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) on Fort Lewis, WA. Report to the Land Condition Trend Analysis Program, Fort Lewis, WA. Norfolk, VA: Environment and Engineering Inc. 19 p.

Clegg, M. and A. Lombardi. 2000. Status report for water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) on Fort Lewis, WA. Report to the Land Condition Trend Analysis Program, Fort Lewis, WA. Norfolk, VA: Environment and Engineering Inc. 19 p. Davis, L. 2004. Flathead National Forest, FY05 – year report of annual monitoring requirements. Annual monitoring of water howellia occurrences. Flathead National Forest, MT: Unpublished report. 10 p.

Davis, L. 2004. Flathead National Forest, FY05 – year report of annual monitoring requirements. Annual monitoring of water howellia occurrences. Flathead National Forest, MT: Unpublished report. 10 p. Erhardt, Brenda. 2025. Water Howellia (Howellia aquatilis) Monitoring in Northern Idaho 2005-2024. July 31st. DRAFT Addendum to Lichthardt and Pekas (2019). Latah Soil and Water Conservation District, Idaho.

Erhardt, Brenda. 2025. Water Howellia (Howellia aquatilis) Monitoring in Northern Idaho 2005-2024. July 31st. DRAFT Addendum to Lichthardt and Pekas (2019). Latah Soil and Water Conservation District, Idaho. Frissell, C. A., J. T. Gangemi, and J. A. Stanford. 1995. Identifying priority areas for protection and restoration of aquatic biodiversity: A case study in the Swan River basin, Montana, USA. Open File Report No. 136-95. Flathead Lake Biological Station, The University of Montana, Polson. 51 pp.

Frissell, C. A., J. T. Gangemi, and J. A. Stanford. 1995. Identifying priority areas for protection and restoration of aquatic biodiversity: A case study in the Swan River basin, Montana, USA. Open File Report No. 136-95. Flathead Lake Biological Station, The University of Montana, Polson. 51 pp. Gamon, J. 1992. Report on the status in Washington of Howellia aquatilis Gray. Washington Natural Heritage Program, Olympia. 46 pp.

Gamon, J. 1992. Report on the status in Washington of Howellia aquatilis Gray. Washington Natural Heritage Program, Olympia. 46 pp. Gamon, J. 1998. Endangered species management plan for water howellia. Washington Natural Heritage Program, Department of Natural Resources.

Gamon, J. 1998. Endangered species management plan for water howellia. Washington Natural Heritage Program, Department of Natural Resources. Gamon, J. 1999. Inventory management plan for water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) on Fort Lewis. Final Reports. Washington Natural Heritage Program, WA Department of Natural Resources in coordination with The Nature Conservancy of Washington.

Gamon, J. 1999. Inventory management plan for water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) on Fort Lewis. Final Reports. Washington Natural Heritage Program, WA Department of Natural Resources in coordination with The Nature Conservancy of Washington. Gamon, J. and T. Rush. 1998. Definition of potential habitat and a monitoring plan for water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) on Fort Lewis. Washington Natural Heritage Program, WA Department of Natural Resources in coordination with The Nature Conservancy o

Gamon, J. and T. Rush. 1998. Definition of potential habitat and a monitoring plan for water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) on Fort Lewis. Washington Natural Heritage Program, WA Department of Natural Resources in coordination with The Nature Conservancy o Gilbert, R. 2002. Field report for water howellia surveys on Fort Lewis, WA. Report to the Land Condition Trend Analysis Program, Fort Lewis, WA. Environment and Engineering Inc., Norfolk, VA. 17 pp.

Gilbert, R. 2002. Field report for water howellia surveys on Fort Lewis, WA. Report to the Land Condition Trend Analysis Program, Fort Lewis, WA. Environment and Engineering Inc., Norfolk, VA. 17 pp. Gilbert, R. and A. Lombardi. 1999. Status report for water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) on Fort Lewis, WA. Report to the Land Condition Trend Analysis Program, Fort Lewis, WA. Environment and Engineering Inc., Norfolk, VA. 25 pp.

Gilbert, R. and A. Lombardi. 1999. Status report for water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) on Fort Lewis, WA. Report to the Land Condition Trend Analysis Program, Fort Lewis, WA. Environment and Engineering Inc., Norfolk, VA. 25 pp. Griggs, F.T. and J.E. Dibble. 1979. Status report, Howellia aquatilis A. Gray. for the Mendocino National Forest. Unpublished report. Mendocino National Forest, CA. 12 pp.

Griggs, F.T. and J.E. Dibble. 1979. Status report, Howellia aquatilis A. Gray. for the Mendocino National Forest. Unpublished report. Mendocino National Forest, CA. 12 pp. Isle, D.W. 1997. Rediscovery of water howellia for California. Fremontia 25(3): 29-32.

Isle, D.W. 1997. Rediscovery of water howellia for California. Fremontia 25(3): 29-32. Jokerst, J.D. 1980. Status report, Howellia aquatilis A. Gray. for the Mendocino National Forest. Unpublished report. California State University, Chico. 18 pp.

Jokerst, J.D. 1980. Status report, Howellia aquatilis A. Gray. for the Mendocino National Forest. Unpublished report. California State University, Chico. 18 pp. Lesica, P. 1991. Monitoring Howellia aquatilis and Phalaris arundinacea at Swan River Oxbow Preserve. Progress report. The Nature Conservancy, Helena, Montana. 7 pp.

Lesica, P. 1991. Monitoring Howellia aquatilis and Phalaris arundinacea at Swan River Oxbow Preserve. Progress report. The Nature Conservancy, Helena, Montana. 7 pp. Lesica, P. 1994. Monitoring Howellia aquatilis at Swan River Oxbow Preserve 1994 Progress Report. Unpublished report to The Nature Conservancy Montana Field Office, Helena, Montana. 5 pp.

Lesica, P. 1994. Monitoring Howellia aquatilis at Swan River Oxbow Preserve 1994 Progress Report. Unpublished report to The Nature Conservancy Montana Field Office, Helena, Montana. 5 pp. Lesica, P. 1994. Monitoring Howellia aquatilis at Swan River Oxbow Preserve: 1993 progress report. Unpublished report prepared for the Montana Nature Conservancy, Helena. 5 pp.

Lesica, P. 1994. Monitoring Howellia aquatilis at Swan River Oxbow Preserve: 1993 progress report. Unpublished report prepared for the Montana Nature Conservancy, Helena. 5 pp. Lesica, P. 1995. Monitoring Howellia aquatilis at Swan River Oxbow Preserve 1995 Progress Report. Unpublished report prepared for The Nature Conservancy Montana Field Office, Helena, Montana. 4 pp.

Lesica, P. 1995. Monitoring Howellia aquatilis at Swan River Oxbow Preserve 1995 Progress Report. Unpublished report prepared for The Nature Conservancy Montana Field Office, Helena, Montana. 4 pp. Lesica, P. 1996. Monitoring Howellia aquatilis at Swan River Oxbow Preserve; 1994 Final Report. Report to The Nature Conservancy, Montana Field Office, Helena, MT. 6 pp.

Lesica, P. 1996. Monitoring Howellia aquatilis at Swan River Oxbow Preserve; 1994 Final Report. Report to The Nature Conservancy, Montana Field Office, Helena, MT. 6 pp. Lesica, P. 1997. Spread of Phalaris arundinacea adversely impacts the endangered plant Howellia aquatilis. Great Basin Naturalist, 57(4): 366-368.

Lesica, P. 1997. Spread of Phalaris arundinacea adversely impacts the endangered plant Howellia aquatilis. Great Basin Naturalist, 57(4): 366-368. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Lesica, P., R.F. Leary and F.W. Allendorf. 1987. Lack of genetic diversity within and among populations of the rare plant Howellia aquatilis. Unpublished report, submitted to The Nature Conservancy, Helena, Montana. 15 pp.

Lesica, P., R.F. Leary and F.W. Allendorf. 1987. Lack of genetic diversity within and among populations of the rare plant Howellia aquatilis. Unpublished report, submitted to The Nature Conservancy, Helena, Montana. 15 pp. Lichthardt, J. and K. Gray. 2001. Monitoring of Howellia aquatilis (water howellia) and its habitat at the Harvard-Palouse River Flood Plain Site, Idaho: Third-year results. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Idaho Conservation Data Center, Boise, ID. 8 p

Lichthardt, J. and K. Gray. 2001. Monitoring of Howellia aquatilis (water howellia) and its habitat at the Harvard-Palouse River Flood Plain Site, Idaho: Third-year results. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Idaho Conservation Data Center, Boise, ID. 8 p Lichthardt, J. and K. Gray. 2003. Monitoring of Howellia aquatilis (water howellia) and its habitat at the Harvard-Palouse River Flood Plain Site, Idaho: Fourth-year results. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Idaho Conservation Data Center, Boise, ID. 8

Lichthardt, J. and K. Gray. 2003. Monitoring of Howellia aquatilis (water howellia) and its habitat at the Harvard-Palouse River Flood Plain Site, Idaho: Fourth-year results. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Idaho Conservation Data Center, Boise, ID. 8 Lichthardt, J. and K. Gray. 2005. Monitoring of Howellia aquatilis (water howellia) and its habitat at the Harvard-Palouse River Flood Plain Site, Idaho: Fifth-year results. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Idaho Conservation Data Center, Boise, ID. 10

Lichthardt, J. and K. Gray. 2005. Monitoring of Howellia aquatilis (water howellia) and its habitat at the Harvard-Palouse River Flood Plain Site, Idaho: Fifth-year results. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Idaho Conservation Data Center, Boise, ID. 10 Lichthardt, J. and R. Moseley. 2000. Ecological assessment of Howellia aquatilis habitat at the Harvard-Palouse River flood plain site. Boise, ID. Unpublished report. Prepared for the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation by the Idaho Department of Fis

Lichthardt, J. and R. Moseley. 2000. Ecological assessment of Howellia aquatilis habitat at the Harvard-Palouse River flood plain site. Boise, ID. Unpublished report. Prepared for the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation by the Idaho Department of Fis Mantas, M. 1998. Historical vs. current conditions of upland forests surrounding Howellia aquatilis habitats in the Swan Valley, MT. In: Forum on Research and Management of Howellia aquatilis. Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, Cheney, WA. March 24-25.

Mantas, M. 1998. Historical vs. current conditions of upland forests surrounding Howellia aquatilis habitats in the Swan Valley, MT. In: Forum on Research and Management of Howellia aquatilis. Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, Cheney, WA. March 24-25. Mantas, M. 2000. Status of Water Howellia (Howellia aquatilis) and Reed Canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea) in Water Howellia Ponds: 1998 and 1999, Swan Valley, Montana.

Mantas, M. 2000. Status of Water Howellia (Howellia aquatilis) and Reed Canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea) in Water Howellia Ponds: 1998 and 1999, Swan Valley, Montana. Mantas, M. 2002. Status of water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) and reed canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea) in water howellia ponds: 1998-2001. Flathead National Forest, MT.

Mantas, M. 2002. Status of water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) and reed canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea) in water howellia ponds: 1998-2001. Flathead National Forest, MT. McCarten, N. and R. Bittman. 1998. Water chemistry, nutrient cycling, productivity and environmental factors affecting plant community structure in Howellia aquatilis ponds. In: Forum on Research and Management of Howellia aquatilis. Turnbull National Wil

McCarten, N. and R. Bittman. 1998. Water chemistry, nutrient cycling, productivity and environmental factors affecting plant community structure in Howellia aquatilis ponds. In: Forum on Research and Management of Howellia aquatilis. Turnbull National Wil McCune, B. 1982. Noteworthy collections - Montana: Howellia aquatilis. Madrono 29:123-124.

McCune, B. 1982. Noteworthy collections - Montana: Howellia aquatilis. Madrono 29:123-124. Rice, D.J. 1989. Short-term protection of Howellia aquatilis: East Pond study area, Dishman Hills Natural Resource Conservation Area, Spokane, WA. Report to Department of Natural Resources. 13 pp.

Rice, D.J. 1989. Short-term protection of Howellia aquatilis: East Pond study area, Dishman Hills Natural Resource Conservation Area, Spokane, WA. Report to Department of Natural Resources. 13 pp. Rice, D.J. 1990. An application of restoration ecology to the management of an endangered plant, Howellia aquatilis [M.S. thesis]. Washington State Univ., Pullman, WA. 85 pp.

Rice, D.J. 1990. An application of restoration ecology to the management of an endangered plant, Howellia aquatilis [M.S. thesis]. Washington State Univ., Pullman, WA. 85 pp. Roe, L.S. and J.S. Shelly. 1992. Update to the status review of Howellia aquatilis: field surveys, monitoring studies, and transplant experiments. Unpublished report to the Flathead National Forest. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT 51 pp.

Roe, L.S. and J.S. Shelly. 1992. Update to the status review of Howellia aquatilis: field surveys, monitoring studies, and transplant experiments. Unpublished report to the Flathead National Forest. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT 51 pp. Schassberger, L.A. and J.S. Shelly. 1991. Update to the status review of Howellia aquatilis: field surveys, monitoring studies, and transplant experiments 1990. Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Flathead National Forest. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT 57 pp.

Schassberger, L.A. and J.S. Shelly. 1991. Update to the status review of Howellia aquatilis: field surveys, monitoring studies, and transplant experiments 1990. Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Flathead National Forest. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT 57 pp. Shapley, M. 1998. Field chemistry and basin geomorphology of Montana’s Howellia aquatilis ponds (Abstract). In: Forum on Research and Management of Howellia aquatilis. Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, Cheney, WA. March 24-25.

Shapley, M. 1998. Field chemistry and basin geomorphology of Montana’s Howellia aquatilis ponds (Abstract). In: Forum on Research and Management of Howellia aquatilis. Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, Cheney, WA. March 24-25. Shapley, M. 1998. Preliminary evaluation of basin morphometry and field chemistry of Montana's Howellia aquatilis ponds. Prepared for Flathead National Forest and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 7pp. plus appendices.

Shapley, M. 1998. Preliminary evaluation of basin morphometry and field chemistry of Montana's Howellia aquatilis ponds. Prepared for Flathead National Forest and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 7pp. plus appendices. Shapley, M. and P. Lesica. 1997. Howellia aquatilis (Water Howellia) ponds of the Swan Valley: conceptual hydrologic models and ecological implications. Unpublished report to the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Montana Natural Heritage Program and Conservation Biology Research. Helena 44 pp.

Shapley, M. and P. Lesica. 1997. Howellia aquatilis (Water Howellia) ponds of the Swan Valley: conceptual hydrologic models and ecological implications. Unpublished report to the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Montana Natural Heritage Program and Conservation Biology Research. Helena 44 pp. Shelly, J.S. 1988. Distribution and status of Howellia aquatilis A. Gray (Campanulaceae) in Lake and Missoula Counties, Montana. Proceedings of Montana Acadamy Science. 48:12. (Abstract)

Shelly, J.S. 1988. Distribution and status of Howellia aquatilis A. Gray (Campanulaceae) in Lake and Missoula Counties, Montana. Proceedings of Montana Acadamy Science. 48:12. (Abstract) Shelly, J.S. 1989. Addendum to the status review of Howellia aquatilis, USDA Forest Service, Region 1, Flathead National Forest, Montana. Unpublished report to the U.S. Forest Service, Region 1. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT 17 pp.

Shelly, J.S. 1989. Addendum to the status review of Howellia aquatilis, USDA Forest Service, Region 1, Flathead National Forest, Montana. Unpublished report to the U.S. Forest Service, Region 1. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT 17 pp. Shelly, J.S. 1994. Conservation strategy, Howellia aquatilis, Flathead National Forest. Unpublished report. USDA Forest Service, Northern Region 26 pp.

Shelly, J.S. 1994. Conservation strategy, Howellia aquatilis, Flathead National Forest. Unpublished report. USDA Forest Service, Northern Region 26 pp. Shelly, J.S. 1995. Howellia aquatilis: Montana's first federally listed plant species. Kelseya, Newsletter of the Montana Native Plant Society.

Shelly, J.S. 1995. Howellia aquatilis: Montana's first federally listed plant species. Kelseya, Newsletter of the Montana Native Plant Society. Shelly, J.S. 1998. Howellia aquatilis – ten years of monitoring, Swan Valley, MT. In: Forum on Research and Management of Howellia aquatilis. Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, Cheney, WA. March 24-25.

Shelly, J.S. 1998. Howellia aquatilis – ten years of monitoring, Swan Valley, MT. In: Forum on Research and Management of Howellia aquatilis. Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, Cheney, WA. March 24-25. Shelly, J.S. 1998. Translocation experiments, Swan Valley, MT. In: Forum on Research and Management of Howellia aquatilis. Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, Cheney, WA. March 24-25.

Shelly, J.S. 1998. Translocation experiments, Swan Valley, MT. In: Forum on Research and Management of Howellia aquatilis. Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, Cheney, WA. March 24-25. Shelly, J.S. 2015. Draft Monitoring Report for Howellia aquatilis. US Forest Service, Region 1, Missoula, Montana.

Shelly, J.S. 2015. Draft Monitoring Report for Howellia aquatilis. US Forest Service, Region 1, Missoula, Montana. Shelly, J.S. and L.A. Schassberger. 1990. Update to the status review of Howellia aquatilis: field surveys, monitoring studies, and transplant experiments, 1989. Unpublished report to the Flathead National Forest, Kalispell, MT. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT 50 pp.

Shelly, J.S. and L.A. Schassberger. 1990. Update to the status review of Howellia aquatilis: field surveys, monitoring studies, and transplant experiments, 1989. Unpublished report to the Flathead National Forest, Kalispell, MT. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT 50 pp. Shelly, S. 1995. Eccentric aquatic. Reprinted in the Conservationist's Notebook feature of American Horticulturalist 74(11):11.

Shelly, S. 1995. Eccentric aquatic. Reprinted in the Conservationist's Notebook feature of American Horticulturalist 74(11):11. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; Proposed listing of water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) as threatened. Federal Register 58(72): 19795-19800.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; Proposed listing of water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) as threatened. Federal Register 58(72): 19795-19800. USDA Forest Service. 1994. Conservation strategy for Howellia aquatilis A. Gray. USDA Forest Service, Flathead National Forest. 26 pp.

USDA Forest Service. 1994. Conservation strategy for Howellia aquatilis A. Gray. USDA Forest Service, Flathead National Forest. 26 pp. USDA Forest Service. 1997. Conservation strategy for Howellia aquatilis A. Gray (second edition). USDA Forest Service, Flathead National Forest. 24 pp.

USDA Forest Service. 1997. Conservation strategy for Howellia aquatilis A. Gray (second edition). USDA Forest Service, Flathead National Forest. 24 pp. Washington Natural Heritage Program. 2005. WA Natural Heritage Information System - March 2, 2005. Olympia, WA.

Washington Natural Heritage Program. 2005. WA Natural Heritage Information System - March 2, 2005. Olympia, WA. Woessner, W. W. and B. Heidel. 1999. Progress Report 7/99-11/99. Preserving the function of unique wetlands critical to survival of water howellia in the Swan Valley, Montana. Report prepared for the Montana Department of Environmental Quality.

Woessner, W. W. and B. Heidel. 1999. Progress Report 7/99-11/99. Preserving the function of unique wetlands critical to survival of water howellia in the Swan Valley, Montana. Report prepared for the Montana Department of Environmental Quality. Wolfold, L. 2003. Water howellia monitoring on Fort Lewis, 2003. Report to the Land Condition Trend Analysis Program, Fort Lewis, WA. Environment and Engineering Inc., Norfolk, VA. 17 pp.

Wolfold, L. 2003. Water howellia monitoring on Fort Lewis, 2003. Report to the Land Condition Trend Analysis Program, Fort Lewis, WA. Environment and Engineering Inc., Norfolk, VA. 17 pp. Wolfold, L. 2004. Water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) monitoring on Fort Lewis Military Reservation field report, 2004. Report to the Land Condition Trend Analysis Program, Fort Lewis, WA. Environment and Engineering Inc., Norfolk, VA. 22 pp.

Wolfold, L. 2004. Water howellia (Howellia aquatilis) monitoring on Fort Lewis Military Reservation field report, 2004. Report to the Land Condition Trend Analysis Program, Fort Lewis, WA. Environment and Engineering Inc., Norfolk, VA. 22 pp.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Water Howellia"