View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Twice-hairy Butterweed - Senecio fuscatus

Other Names:

Senecio lindstroemii, Senecio tundricola, Tephroseris lindstroemii

Native Species

Global Rank:

G4

State Rank:

S3S4

(see State Rank Reason below)

C-value:

Agency Status

USFWS:

USFS:

BLM:

External Links

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

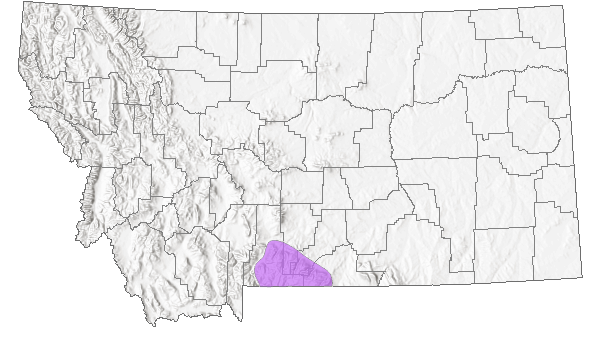

Senecio fuscatus occurs in south-central Montana where populations appear to be relatively common or stable where habitat is present. Although population sizes are unknown and its distribution in Montana is small, the number of herbarium collections and information indicate a more commonly occurring plant.

- Details on Status Ranking and Review

Population Size

ScoreU - Unknown

Range Extent

ScoreC - 250-1,000 sq km (~100-400 sq mi)

Area of Occupancy

ScoreD - 6-25 4-km2 grid cells

Number of Populations

ScoreC - 21 - 80

Number of Occurrences or Percent Area with Good Viability / Ecological Integrity

ScoreC - Few (4-12) occurrences with excellent or good viability or ecological integrity

Long-term Trend

ScoreU - Unknown

Trends

ScoreU - Unknown

Threats

ScoreD - Low

CommentNo known threats. Occurs in predominately protected or little used areas.

General Description

Plants: Perennial herb with a “short, rhizome-like woody stem-base” (Douglas et al. 1998), fibrous-rooted; stems erect, 8–25 cm (Lesica 2012), 1 to several, each having its own set of basal leaves; herbage densely covered with cobweb-like hairs (arachnoid), or long, soft strands (villous) accompanied by woolly hairs (tomentose), part of the tomentum falling away eventually (Hitchcock et al. 1955).

Leaves: Basal leaves 3-7 cm in length, 8-22 mm in width, persistent; basal leaf blades broadly lanceolate (Hitchcock et al. 1955) to obovate (Lesica 2012), with a wide sessile or winged subpetiolate base, generally well-supplied with persistent, appressed, glandular hairs beneath the tomentum; margins smooth to somewhat wavy. Cauline leaves sessile, becoming smaller upwards, narrowing to become lance-acuminate (Hitchcock et al. 1955).

Inflorescence & Heads: Inflorescence with 2 to 8 heads (Lesica 2012), closely clustered, the terminal head the biggest (Hitchcock et al. 1955). Heads radiate; involucres 5–10 mm high; phyllaries ca 21, glabrate, purplish (Lesica 2012), lacking bracteoles; disk 1-2 cm in width (Hitchcock et al. 1955).

(Lesica's contribution adapted from

Lesica et al. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. BRIT Press. Fort Worth, TX).

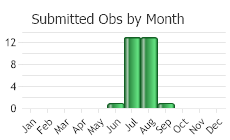

Phenology

Flowering June-August (FNA 2006).

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

Circumpolar (Lesica 2012), including nw BC (rare), north to AK, YT and NT, disjunct in MT and WY (Douglas et al. 1998), and in the Far East of Russia (FNA 2006).

(Lesica's contribution adapted from Lesica et al. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. BRIT Press. Fort Worth, TX)

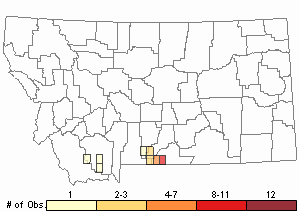

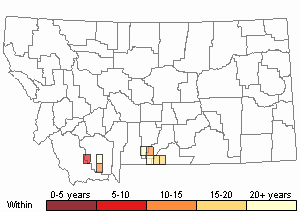

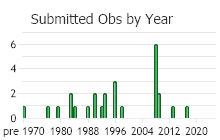

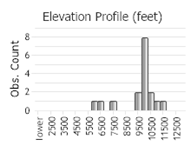

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 30

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Open tundra and alpine meadows; 3280-10,500 feet (FNA 2006).

Ecology

S. fuscatus is a circumpolar alpine and tundra species. In Montana and Wyoming, it is known to grow in the high Beartooth Plateau. Northwest of Montana, it appears not to occur again until in far northwestern British Columbia, becoming more common in the Yukon and Alaska (Douglas et al. 1998). K.L. Marr, R.J. Hebda, and W.H. MacKenzie (2012) found that twelve species adapted to arctic-alpine tundra conditions, including

S. fuscatus, showed similarities in their disjunct distributions. The authors offer the explanation that during the Pleistocene, suitable habitat was more extensive for these species, allowing them to spread. With the warming climate of the Holocene, they became extinct in many areas. Quite possibly, for thousands of years, the cool Beartooth Plateau has provided a refugium for

S. fuscatus and at least nine other species, plant traveler companions in time and space.

The boreal woodland extends into the MacKenzie River Delta in Canada. Here, black spruce (

Picea mariana) and/or white spruce (

P. glauca) rise above a groundlayer of dwarf birch (

Betula glandulosa), alder (

Alnus spp.), willow (

Salix spp.), members of the Blueberry family, and bryophytes (Gill 1974). Gill studied clearings along the MacKenzie River’s upper levees where Eskimos removed trees and shrubs from around their dwellings.

Senecio fuscatus, which lives in alpine areas scantily-vegetated (Polunin 1959; Hultén 1968), had apparently come in along with other tundra species through wind dispersal. These appeared to be thriving in the clearcut areas. Spruce seedlings, on the other hand, lacked vigor and died (Gill 1974).

In areas of permafrost, additional stress from human activities such as clearcutting could possibly tip the vegetative balance from a former coniferous forest to a tundra cover.

S. fuscatus was an important indicator that retrogression was occurring in the clearcut areas of the coniferous forest (Gill 1974).

POLLINATORS The following animal species have been reported as pollinators of this plant species or its genus where their geographic ranges overlap:

Bombus bifarius,

Bombus flavifrons,

Bombus frigidus,

Bombus huntii,

Bombus melanopygus,

Bombus mixtus,

Bombus sylvicola,

Bombus occidentalis,

Bombus insularis,

Bombus suckleyi,

Bombus flavidus, and

Bombus kirbiellus (Schmitt 1980, Thorp et al. 1983, Mayer et al. 2000, Wilson et al. 2010, Pyke et al. 2012, Koch et al. 2012, Williams et al. 2014).

Reproductive Characteristics

Flowers & Fruit: Rays orange (Hitchcock et al. 1955), numbering 13 or 21; ligules 8–14 mm long. Disk corollas 5–7 mm long, orangish; pappus of white capillary bristles. Achenes 2–4 mm long, pubescent (Lesica 2012).

(Lesica's contribution adapted from

Lesica et al. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. BRIT Press. Fort Worth, TX).

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Cody, W.J. 1996. The flora of the Yukon Territory. National Research Council of Canada Research Press, Ottawa, Canada. 643 pp.

Cody, W.J. 1996. The flora of the Yukon Territory. National Research Council of Canada Research Press, Ottawa, Canada. 643 pp. Douglas, G.W., G.B. Straley, D. Meidinger, and J. Pojar, editors. 1998. The Illustrated Flora of British Columbia. Volume 1. Gynmosperms and Dicotyledons (Aceraceae through Asteraceae). British Columbia Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks and British Columbia Ministry of Forests, Victoria.

Douglas, G.W., G.B. Straley, D. Meidinger, and J. Pojar, editors. 1998. The Illustrated Flora of British Columbia. Volume 1. Gynmosperms and Dicotyledons (Aceraceae through Asteraceae). British Columbia Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks and British Columbia Ministry of Forests, Victoria. Flora of North America Editorial Committee. 2006. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 20. Magnoliophyta: Asteridae, part 7: Asteraceae, part 2. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. xxii + 666 pp.

Flora of North America Editorial Committee. 2006. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 20. Magnoliophyta: Asteridae, part 7: Asteraceae, part 2. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. xxii + 666 pp. Gill, D. 1974. Forestry operations in the Canadian Subarctic: an ecological argument against clear-cutting. Environmental Conservation 1(2):87-92.

Gill, D. 1974. Forestry operations in the Canadian Subarctic: an ecological argument against clear-cutting. Environmental Conservation 1(2):87-92. Hitchcock, C.L. 1955. Compositae. In C.L. Hitchcock, A. Cronquist, M. Ownbey, and J.W. Thompson (eds.). Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest. Part 5: Compositae. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 343 pp.

Hitchcock, C.L. 1955. Compositae. In C.L. Hitchcock, A. Cronquist, M. Ownbey, and J.W. Thompson (eds.). Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest. Part 5: Compositae. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 343 pp. Hulten, E. 1968. Flora of Alaska and Neighboring Territories. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA.

Hulten, E. 1968. Flora of Alaska and Neighboring Territories. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. Koch, J., J. Strange, and P. Williams. 2012. Bumble bees of the western United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 143 p.

Koch, J., J. Strange, and P. Williams. 2012. Bumble bees of the western United States. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, Pollinator Partnership. 143 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Marr, K.L., R.J. Hebda, and W.H. MacKenzie. 2012. New alpine plant records for British Columbia and a previously unrecognized biogeographical element in western North America. Botany 90:445-455.

Marr, K.L., R.J. Hebda, and W.H. MacKenzie. 2012. New alpine plant records for British Columbia and a previously unrecognized biogeographical element in western North America. Botany 90:445-455. Mayer, D.F., E.R. Miliczky, B.F. Finnigan, and C.A. Johnson. 2000. The bee fauna (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of southeastern Washington. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 97: 25-31.

Mayer, D.F., E.R. Miliczky, B.F. Finnigan, and C.A. Johnson. 2000. The bee fauna (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of southeastern Washington. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 97: 25-31. Polunin, N. 1959. Circumpolar Arctic Flora. Oxford: Clarendon Press, and London: Oxford University Press. xxviii+514 p.

Polunin, N. 1959. Circumpolar Arctic Flora. Oxford: Clarendon Press, and London: Oxford University Press. xxviii+514 p. Pyke, G.H., D.W. Inouye, and J.D. Thomson. 2012. Local geographic distributions of bumble bees near Crested Butte, Colorado: competition and community structure revisited. Environmental Entomology 41(6): 1332-1349.

Pyke, G.H., D.W. Inouye, and J.D. Thomson. 2012. Local geographic distributions of bumble bees near Crested Butte, Colorado: competition and community structure revisited. Environmental Entomology 41(6): 1332-1349. Schmitt, J. 1980. Pollinator foraging behavior and gene dispersal in Senecio (Compositae). Evolution 34: 934-943.

Schmitt, J. 1980. Pollinator foraging behavior and gene dispersal in Senecio (Compositae). Evolution 34: 934-943. Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79.

Thorp, R.W., D.S. Horning, and L.L. Dunning. 1983. Bumble bees and cuckoo bumble bees of California (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Bulletin of the California Insect Survey 23:1-79. Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p.

Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 208 p. Wilson, J.S., L.E. Wilson, L.D. Loftis, and T. Griswold. 2010. The montane bee fauna of north central Washington, USA, with floral associations. Western North American Naturalist 70(2): 198-207.

Wilson, J.S., L.E. Wilson, L.D. Loftis, and T. Griswold. 2010. The montane bee fauna of north central Washington, USA, with floral associations. Western North American Naturalist 70(2): 198-207.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Aho, Ken Andrew. 2006. Alpine and Cliff Ecosystems in the North-Central Rocky Mountains. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 343 p.

Aho, Ken Andrew. 2006. Alpine and Cliff Ecosystems in the North-Central Rocky Mountains. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 343 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Martin, S.A. 1985. Ecology of the Rock Creek bighorn sheep herd, Beartooth Mountains, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 152 p.

Martin, S.A. 1985. Ecology of the Rock Creek bighorn sheep herd, Beartooth Mountains, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 152 p. Pallister, G.L. 1974. The seasonal distribution and range use of bighorn sheep in the Beartooth Mountains, with special reference to the West Rosebud and Stillwater herds. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 67 p.

Pallister, G.L. 1974. The seasonal distribution and range use of bighorn sheep in the Beartooth Mountains, with special reference to the West Rosebud and Stillwater herds. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 67 p. Williams, K.L. 2012. Classification of the grasslands, shrublands, woodlands, forests and alpine vegetation associations of the Custer National Forest portion of the Beartooth Mountains in southcentral Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 376 p.

Williams, K.L. 2012. Classification of the grasslands, shrublands, woodlands, forests and alpine vegetation associations of the Custer National Forest portion of the Beartooth Mountains in southcentral Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 376 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Twice-hairy Butterweed"