View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Northern Rocky Mountains Refugium Caddisfly - Rossiana montana

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

This NRMR Caddisfly is currently ranked a "S2" Species of Concern in MT and at risk because of very limited and/or potentially declining population numbers, range and/or habitat, making it vulnerable to extirpation in the state. Limited sites with small populations and specialized habitats. This species is a rare, endemic caddisfly only found in specific streams in the Pacific Influenced areas of Montana and Idaho (referred to as the Northern Rocky Mountian Refugium).

- Details on Status Ranking and Review

Northern Rocky Mountains Refugium Caddisfly (Rossiana montana) Conservation Status Review

Review Date = 09/18/2008

Population Size

ScoreU - Unknown

CommentUnknown.

Range Extent

ScoreB - 100-250 km squared (about 40-100 square miles)

Comment<100-250 square km (less than about 40-100 square miles)

Area of Occupancy

Comment40-200 km (25-125 miles) linear river

Length of Occupancy

ScoreLC - 40-200 km (about 25-125 miles)

Long-term Trend

ScoreD - Moderate Decline (decline of 25-50%)

CommentSiltation and stream temperature increases with loss of riparian shading and lower snowpack probably contributed to some decline

Short-term Trend

ScoreE - Stable. Population, range, area occupied, and/or number or condition of occurrences unchanged or remaining within ±10% fluctuation

Threats

ScoreF - Widespread, low-severity threat. Threat is of low severity but affects (or would affect) most or a significant portion of the population or area.

CommentClimate Change, increasing stream temperatures and lower snowpack could seriously impact the habitat that this speces exists in

SeverityLow - Low but nontrivial reduction of species population or reversible degradation or reduction of habitat in area affected, with recovery expected in 10-50 years.

ScopeModerate - 20-60% of total population or area affected

ImmediacyLow - Threat is likely to be operational within 5-20 years.

CommentThreat is not fully operational now, but some areas have been lost.

Intrinsic Vulnerability

ScoreC - Not Intrinsically Vulnerable. Species matures quickly, reproduces frequently, and/or has high fecundity such that populations recover quickly (< 5 years or 2 generations) from decreases in abundance; or species has high dispersal capability such that extirpated populations soon become reestablished through natural recolonization (unaided by humans).

Environmental Specificity

ScoreB - Narrow. Specialist. Specific habitat(s) or other abiotic and/or biotic factors (see above) are used or required by the Element, but these key requirements are common and within the generalized range of the species within the area of interest.

CommentCold water stenotherm, cannot survive increases in water temperatures or will have to migrart to cooler temps

General Description

Trichoptera is the largest and most diverse order of insects that is primarily aquatic, with about 13,000 species worldwide (Holzenthal et al. 2007, de Moor and Ivanov 2008). The roots of Trichopteran lineages date back to at least the middle of the Jurassic period (Holzenthal et al. 2007). Caddisfly larvae are vital contributors to aquatic food webs and their presence is often used when assessing water quality. Caddisflies are most closely related to Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), and they share characteristics such as spinning silk. Adult caddisflies are medium-sized insects with tent-shaped wings. They resemble moths, but caddisflies do not have a coiled proboscis and their wings are covered in hairs rather than scales. They tend to be secretive and slow-flying riparian insects (Anderson 1976).

Caddisflies spend much of their life in the water as aquatic larvae and most species build portable, protective cases made from plant material or stones. These cases are incredibly intricate and complex structures, especially for a non-social insect (Holzenthal et al. 2007). Trichopteran larvae have well-developed mouthparts; mandibles of shredders are broad with cutting teeth, while the mandibles of scrapers are more elongated with entire edges. Abdominal gills are present in most species.

Caddisflies typically have five larval instars before pupation (Wiggins 1996). During pupation, the insect’s antennae, legs, and developing wings are free from the body, and characteristics can still be used for identification (Holzenthal et al. 2007). Adult caddisflies are terrestrial and usually dully colored. This order of insects is very diverse and adult body length can range from 1.5mm to 45mm. Unlike Trichopteran larvae, adult caddisflies have reduced mouthparts because they only live from a few days to a couple weeks (Wiggins 1996).

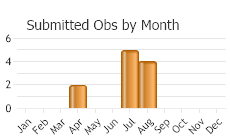

Phenology

Pupae and late-instar larvae were collected in June, so adults may be flying from late-June to July.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Rossiana is one of two genera within the family Rossianidae, and each genus contains only a single species (

Rossiana montana and

Goereilla baumanni) (Holzenthal et al. 2007). The Family Rossianidae is closely related to Goeridae and Uenoidae.

Rossiana montana larvae are =9mm long, have long, single gills, and a uniquely shaped head and pronotum that are red-brown and coarsely pebbled (Wiggins 1996). Their antennae are midway between their eye and the back of their head, and they have an unusually wide separation between the sclerites along their mid-dorsal line. Larvae have toothed mandibles, a tuft of stout setae (hairs), and a peg-shaped sclerite beneath their head (Wiggins 1996).

Rossiana montana has longer basal setae on its middle and hind tarsal claws than

Goereilla baumanni.

Rossiana montana builds larval cases that are =10.5mm long from small rocks. These cases are tubular, slightly curved, and taper towards the back (Wiggins 1996). Larvae have a concave pronotum on each side and a head that acts as a flange. Little is known about the morphology of

Rossiana montana adults .

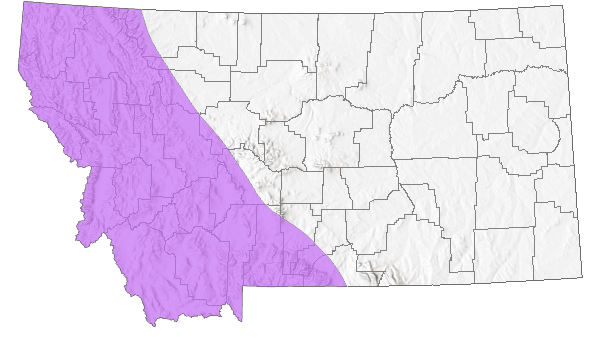

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

Both species that are in the family Rossianidae (Rossiana montana and Goereilla baumanni) are known from western North America. Each species is highly localized and rare within known localities (Wiggins 1996). Rossiana montana is known from Montana, Washington, and British Columbia.

Collected in Manning Park (Allison Pass) in British Columbia (1968; Scudder and Nimmo 1978). Reported from streams in Missoula, Mineral, and Sanders counties (NatureServe 2023). Likely in Idaho along Montana border.

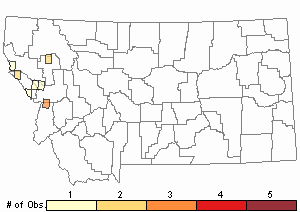

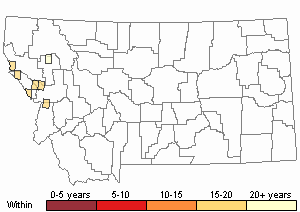

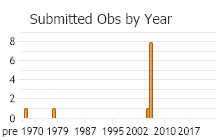

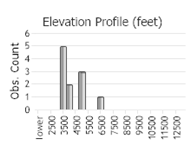

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 11

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

Larval drift and adult movements not studied in Montana.

Habitat

Rossiana montana larvae are found in small, cold, mountain streams. Their occurrence is highly restricted, but they are sometimes found in multiple microhabitats within a stream (Wiggins 1996, Holzenthal et al. 2007). This species is most often found in gravel under moss at the edge of streams or on vertical rocks that have a thin layer of water on them.

Food Habits

Based on gut content examination (Wiggins 1996), Rossiana montana feeds on woody materials and fungi. It is classified as a scraper and a shredder (Morse 2009). Adult caddisflies usually do not have developed mouthparts and only eat nectar, sap, or nothing during their adult lifespan.

Ecology

The trophic relationship of larvae of R. montana includes scrappers and shredders (eating detritus & larger plant materials) (Merritt and Cummins 1996, Wiggins 1996).

Reproductive Characteristics

Little is known about R. montana, but this species is likely spending most of its life feeding in a stream as a larva before emerging as a winged adult in the late summer. Most caddisflies have a univoltine (one-year) life cycle. Rossiana montana collections indicate they likely have a univoltine life cycle due to pupae and larvae of the last three instars being found in June (Wiggins 1996). This means they would spend the autumn through early summer as larvae. Late instar larvae secure their cases to rocks, seal off the case’s entrance, and undergo metamorphosis (Wiggins 1996). Adults emerge several weeks later in late summer (Beam and Wiggins 1987, Wiggins 1996).

More research should be done on the life history of this species because it is also possible for this species to be semivoltine. In intermittent streams, some Trichopteran species sustain pre-pupal diapause until after summer drought, thus delaying adult emergence and breeding (Wiggins 1973, 1996). Larvae can survive up to six months during periods of high-water temperatures or reduced flow using this method. Other species undergo the same process if the growing season (e.g., high altitude mountain streams) is too short. As adults, they use trees as roosting places and live for a few weeks.

Caddisfly adults tend to remain near the emergence site where oviposition occurs. Although dispersal flights are common, they are relatively short and only occur immediately following emergence. Dispersal from emergence sites tends to be negatively correlated with vegetation density (Collier and Smith 1998). In other words, caddisflies tend to disperse shorter distances in dense forest compared with more open areas. As adults, they use trees as roosting places.

Management

Rossiana montana has been described as a rare species due to habitat specificity and is never abundant when collected (Wiggins 1996, Stagliano et al. 2007). It has no USFWS status at the present time, although it is currently a USFS Species of Concern (SOC). It is ranked globally at risk/potentially at risk (G2G3) by Natureserve (2015), and at risk (S2) in Montana, although not yet reported for Idaho.

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Freshwater aquatic habitats are one of the most imperiled ecosystems globally because its water collects all the abuses in the entire watershed area (Holzenthal et al. 2007). Cold-water invertebrates are thought to be specialists and are sensitive to changes in aquatic habitat (e.g., flow patterns, streambed substrate, thermal characteristics, and water quality; Green et al. 2022). Forest riparian area are prone to increases in sediment and temperature when the landscape is disturbed, such as road building and timber harvests, and may make these streams less suitable for cold-water invertebrates (Stagliano et al. 2007). Additionally, researchers have begun studying the effects of climate change on Trichopterans in alpine headwater streams (Brown et al. 2007, Holzenthal et al. 2007), but much more research is need to understand how these insects will respond.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Anderson, N.H. 1976. The distribution and biology of the Oregon Trichoptera. Oregon Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 134:1-152.

Anderson, N.H. 1976. The distribution and biology of the Oregon Trichoptera. Oregon Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 134:1-152. Beam, B.D. and G.B. Wiggins. 1987. A comparative study of the biology of five species of Neophylax (Trichoptera: Limnephilidae) in southern Ontario. Canadian Journal of Zoology 65:1741-1754.

Beam, B.D. and G.B. Wiggins. 1987. A comparative study of the biology of five species of Neophylax (Trichoptera: Limnephilidae) in southern Ontario. Canadian Journal of Zoology 65:1741-1754. Brown, L.E., D.M. Hannah, and A.M. Milner. 2007. Vulnerability of alpine stream biodiversity to shrinking glaciers and snowpacks. Global Change Biology 13:958-966.

Brown, L.E., D.M. Hannah, and A.M. Milner. 2007. Vulnerability of alpine stream biodiversity to shrinking glaciers and snowpacks. Global Change Biology 13:958-966. Collier, K.J. and B.J. Smith. 1998. Dispersal of adult caddisflies (Trichoptera) into forests alongside three New Zealand streams. Hydrobiologia, 361: 53-65.

Collier, K.J. and B.J. Smith. 1998. Dispersal of adult caddisflies (Trichoptera) into forests alongside three New Zealand streams. Hydrobiologia, 361: 53-65. de Moor, F.C. and V.C. Ivanov. 2008. Global diversity of caddisflies (Trichoptera: Insecta) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 595:393-407.

de Moor, F.C. and V.C. Ivanov. 2008. Global diversity of caddisflies (Trichoptera: Insecta) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 595:393-407. Green M.D., L.M. Tronstad, J.J. Giersch, A.A. Shah, C.E. Fallon, E. Blevins, T.R. Kai, C.C. Muhlfeld, D.S. Finn, and S. Hotaling. 2022. Stoneflies in the genus Lednia (Plecoptera: Nemouridae): sentinels of climate change impacts on mountain stream biodiversity. Biodiversity and Conservation. 31: 353-377.

Green M.D., L.M. Tronstad, J.J. Giersch, A.A. Shah, C.E. Fallon, E. Blevins, T.R. Kai, C.C. Muhlfeld, D.S. Finn, and S. Hotaling. 2022. Stoneflies in the genus Lednia (Plecoptera: Nemouridae): sentinels of climate change impacts on mountain stream biodiversity. Biodiversity and Conservation. 31: 353-377. Holzenthal, R.W., R.J. Blahnik, A.L. Prather, and K.M. Kjer. 2007. Order Trichoptera Kirby, 1813 (Insecta), caddisflies. Zootaxa 1668:639-698.

Holzenthal, R.W., R.J. Blahnik, A.L. Prather, and K.M. Kjer. 2007. Order Trichoptera Kirby, 1813 (Insecta), caddisflies. Zootaxa 1668:639-698. Morse, J.C. 2009. Trichoptera (Caddisflies). pp. 1015-1020. In: V.H. Resh and R.T. Carde (eds). Encyclopedia of Insects (Second Edition). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. 1168 p.

Morse, J.C. 2009. Trichoptera (Caddisflies). pp. 1015-1020. In: V.H. Resh and R.T. Carde (eds). Encyclopedia of Insects (Second Edition). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. 1168 p. NatureServe Explorer. 2023. Information on rare and endangered species and ecosystems in the Americas. Accessed 6 March 2023. https://explorer.natureserve.org/

NatureServe Explorer. 2023. Information on rare and endangered species and ecosystems in the Americas. Accessed 6 March 2023. https://explorer.natureserve.org/ Nimmo, A.P. and G.G.E. Scudder. 1978. An annotated checklist of the Trichoptera (Insecta) of British Columbia. Syesis 11: 117-134.

Nimmo, A.P. and G.G.E. Scudder. 1978. An annotated checklist of the Trichoptera (Insecta) of British Columbia. Syesis 11: 117-134. Stagliano, D.M., G.M. Stephens, and W.R. Bosworth. 2007. Aquatic invertebrate species of concern on USFS northern region lands. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana and Idaho Conservation Data Center, Boise, Idaho. 153 p.

Stagliano, D.M., G.M. Stephens, and W.R. Bosworth. 2007. Aquatic invertebrate species of concern on USFS northern region lands. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana and Idaho Conservation Data Center, Boise, Idaho. 153 p. Wiggins, G.B. 1973. A contribution to the biology of caddisflies (Trichoptera) in temporary pools. Toronto, Ontario: Royal Ontario Museum. 28 p.

Wiggins, G.B. 1973. A contribution to the biology of caddisflies (Trichoptera) in temporary pools. Toronto, Ontario: Royal Ontario Museum. 28 p. Wiggins, G.B. 1996. Larvae of the North American caddisfly genera (Trichoptera). University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Ontario. 2nd Edition. 457 p.

Wiggins, G.B. 1996. Larvae of the North American caddisfly genera (Trichoptera). University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Ontario. 2nd Edition. 457 p.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Denning, D. G. 1973. New species of Trichoptera. Pan-Pacific Entomologist 51(4): 318-326.

Denning, D. G. 1973. New species of Trichoptera. Pan-Pacific Entomologist 51(4): 318-326. Merritt, R.W. and K.W. Cummins. 1996. An introduction to the aquatic insects of North America. 3rd Edition. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. Dubuque, Iowa. 862 pp.

Merritt, R.W. and K.W. Cummins. 1996. An introduction to the aquatic insects of North America. 3rd Edition. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. Dubuque, Iowa. 862 pp.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Northern Rocky Mountains Refugium Caddisfly"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Insects"