View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Punctured Tiger Beetle - Cicindela punctulata

Other Names:

Sidewalk Tiger Beetle,

Cicindelidia punctulata

Native Species

Global Rank:

G5

State Rank:

S5

Agency Status

USFWS:

USFS:

BLM:

External Links

General Description

The following is taken from Wallis (1961), Graves and Brzoska (1991), Kippenhan (1994), Knisley and Schultz (1997), Leonard and Bell (1999), Acorn (2001), and Pearson et al (2015). Body length is 10-13 mm. Color is variable above, black, brown, olive or metallic green, blue-green, or rarely bright blue. Maculations reduced to small whitish spots and short thin lines, rarely complete, sometimes completely absent. A row of small but distinct blue-green pits runs parallel to inner margin of the elytra. Body is relatively slender, especially at thorax. Color below is metallic blue-green on abdomen, and coppery-purplish on sides of thorax. Forehead is not hairy, labrum with one tooth, first antennal segment with only one sensory setae.

C. p. punctulata, the only subspecies in Montana, is blackish above with maculations reduced to a few spots and a distinct short but straight line extending inward on outer tip of elytra.

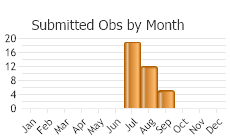

Phenology

Tiger beetle life cycles fit two general categories based on adult activity periods. “Spring-fall” beetles emerge as adults in late summer and fall, then overwinter in burrows before emerging again in spring when mature and ready to mate and lay eggs. The life cycle may take 1-4 years. “Summer” beetles emerge as adults in early summer, then mate and lay eggs before dying. The life cycle may take 1-2 years, possibly longer depending on latitude and elevation (Kippenhan 1994, Knisley and Schultz 1997, and Leonard and Bell 1999). Adult Cicindela (= Cicindelidia) punctulata a summer species, April to November across the range but most active in July (Larochelle and Larivière 2001, and Pearson et al. 2015); June to mid-September in North Dakota and Colorado (Kirk and Balsbaugh 1975, and Kippenhan 1994), June to October in Nebraska (Carter 1989). In Montana, records from late June to late September (Nate Kohler personal communication, iNaturalist 2023).

Diagnostic Characteristics

The following comes from Wallis (1961), Kippenhan (1994), Acorn (2001), and Pearson et al. (2015). The combination of dark body with maculations reduced to a few spots and short thin lines, the row of small blue-green pits parallel to the inner margin of the elytra, the labrum with a single tooth, and a non-hairy forehead, are diagnostic in our region. The dark form of the

Cowpath Tiger Beetle (

Cicindela purpurea auduboni), the

Long-lipped Tiger Beetle (

Cicindela longilabris), and the

Prairie Long-lipped Tiger Beetle (

Cicindela nebraskana) are heavier-bodied (broader) with different maculations (or none) than

Cicindela (= Cicindelidia) punctulata, and all lack the row of small blue-green pits on the elytra.

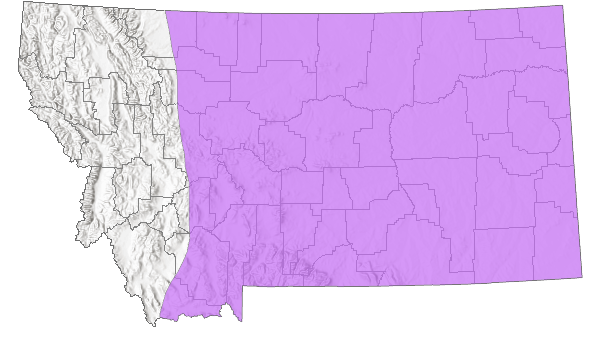

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

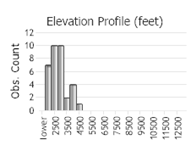

Cicindela (= Cicindelidia) punctulata is present east of the Rocky Mountains across southern Canada from Alberta to Ontario and Nova Scotia, and south throughout the US from Nevada and Arizona to the Atlantic Ocean, to 3505 m (11,500 ft) elevation (Kippenhan 1994, and Pearson et al. 2015). One subspecies is restricted to the central highlands of Mexico. C. p. punctulata, the most widespread of three currently recognized subspecies (one in Mexico, two north of Mexico) and the only one present in Montana, has been reported from at least 24 Montana counties throughout the Great Plains and intermountain valleys east of the Continental Divide, to at least 2030 m (6660 ft) elevation (Winton 2010, Nate Kohler personal communication, Paul Hendricks personal observation, iNaturalist 2023).

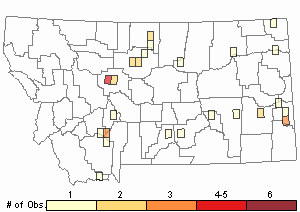

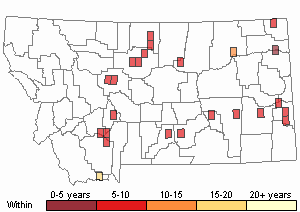

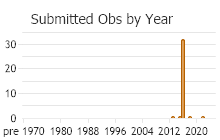

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 49

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

Non-migratory but capable of dispersal. When wings fully developed (macropterous), it is a strong flier, and fast runner; sometimes attracted to lights in cities and the field in large numbers (Larochelle and Larivière 2001).

Habitat

Adult and larval tiger beetle habitat is essentially identical, the larvae live in soil burrows (Knisley and Schultz 1997). Cicindela (= Cicindelidia) punctulata associated with disturbed and undisturbed habitats, including dirt and paved roads, road cuts, roadside ditches, cow paths, dirt paths, eroded banks and gullies, badlands, rocky hillsides, to treeline in high mountains, strip mines, sand dunes, blowouts, sand bars, yards, city lawns and parks, garden paths, grasslands and prairie, pastures, cultivated fields, plowed fields, city vacant lots and parking lots, sidewalks, forest paths, hard-packed open ground that is dry and sparsely vegetated soil of sand or sandy loam, saline flats, lake and river margins, dry mudflats (Vaurie 1950, Willis 1966, Hooper 1969, Kirk and Balsbaugh 1975, Knisley 1984, Carter 1989, Kippenhan 1994, Acorn 2001, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Kritsky and Smith 2005, and Pearson et al. 2015). In Montana, habitat includes stream, river, and pond margins, wetland edges, badlands, large sandy blowouts, dunes, saline flats, sandy two-tracks, grasslands, urban sidewalks (Vaurie 1950, Winton 2010, Nate Kohler personal communication, Paul Hendricks personal observation, and iNaturalist 2023).

Food Habits

Larval and adult tiger beetles predaceous. In general, both feed considerably on ants (Wallis 1961, and Knisley and Schultz 1997). Adult diet in the field includes ants, nymphal seed bugs (lygaeids), grasshoppers (acridids), beetles (chrysomelids, carabids), and worms; in captivity ants, beetles (carabids), flies, and lean meat. Larval diet in the field includes a variety of small arthropods; in captivity flies (drosophilids, muscids, calliphorids), cricket nymphs (gryllids), and lean meat (Mury Meyer 1987, Larochelle and Larivière 2001).

Ecology

Larval tiger beetles live in burrows and molt through three instars to pupation, which also occurs in the larval burrow. Adults make shallow burrows in soil for overnight protection, deeper burrows for overwintering. Adults are sensitive to heat and light and are most active during sunny conditions. Excessive heat during midday on sunny days drives adults to seek shelter among vegetation or in burrows (Wallis 1961, Knisley and Schultz 1997).

Cicindela (= Cicindelidia) punctulata has a broad range of ecological tolerance (eurytopic), occurring in a variety of disturbed and undisturbed habitats. Larval burrows excavated among grass clumps and weeds, dry mossy sites, or willow and cottonwood seedlings, usually in hard-packed sand, clay, or loam, Larvae can survive flooding (hypoxia) up to 180 hours, adults for about 15 hours (Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Brust and Hoback 2009). Adults are both diurnal and nocturnal, gregarious. Basks, stilts, forages, and shuttles to shade at 33.4-37.7°C, inactive at 38-39°C. During hottest times of day seen going in and out of mud cracks or sheltering in shade of vegetation, sticks and rocks; hides under wood on cloudy or cool days. Attracted to artificial lights at night. Very wary during day, sometimes difficult to approach; when pursued makes quick flights, emits strong fruity scent when captured. Predators include birds (bluebirds, grackles,

American crow (

Corvus brachyrhynchos), flycatchers,

European Starling (

Strunus vulgrais),

American Kestrel (

Falco sparverius),

American Robin (Turdus migratorius)), amphibians (frogs, toads), White bass (

Morone chrysops\), asilid (robber) flies, possibly bats; larval parasites include bombyliid flies and tiphiid wasps (Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Brust et al. 2004).

C. punctulata adults especially sensitive to ultrasound in the range of 25-50 kHz and makes nocturnal flights (Vaurie 1950, Yager et al. 2000, and Larochelle and Larivière 2001). Associated tiger beetle species across the range include

Cicindela (=Eunota) circumpicta,

C. decemnotata,

C. denverensis,

C. formosa,

C. fulgida,

C. (=Cicindelidia) hemorrhagica,

C.lengi,

C. limbalis,

C. (=Ellipsoptera) nevadica,

C. (=Cicindelidia) nigrocoerula,

C. (=Cicindelidia) obsoleta,

C. (=Cicindelidia) ocellata,

C. pulchra,

C. purpurea,

C. repanda,

C. sexguttata,

C. (=Parvindela) teriricola,

C. (=Eunota) togata, and

C. tranquebarica (Kippenhan 1994, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Kritsky and Smith 2005, Gotschall et al. 2021).

Reproductive Characteristics

The life cycle of Cicindela (= Cicindelidia) punctulata is 1 year over most of its range, possibly 2 years in the north; overwinters as third-instar larvae (Acorn 2001, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, and Pearson et al. 2015). Adults mate during June-September, (Vaurie 1950, Larochelle and Larivière 2001). Females lay eggs during June-July from the ground surface during the day at depths of 5-8 mm, eggs hatch in about 14 days. Larval burrows about 14-65 cm deep, deeper in winter than summer, duration of larval stage is 10 months, after hibernation larvae feed from April-June; pupation in May-June lasts 10-14 days, tenerals (fresh adults) emerge in May-July, adults live about 2 months (Criddle 1907, Shelford 1908, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Brust et al. 2012, and Pearson et al. 2015). No information about reproductive characteristics in Montana.

Management

Not considered rare or in need of special conservation management (Knisley et al. 2014). As one of the most widespread tiger beetles, especially east of the Rocky Mountains (Pearson et al. 2015), Cicindela (= Cicindelidia) punctulata occurs in many human-altered landscapes, including grazed pastures and rangelands, agricultural fields, orchards, urban yards and clearings, powerline cuts, sandy and clay roads and paths, and can benefit from the maintenance or judicious creations of these habitats in Montana and elsewhere (Knisley 2011). Encroachment of open areas by native or exotic plants through the process of succession might become a problem locally as this species prefers open terrain (Knisley 1979). Local disturbance could also be a problem for some populations where larval burrows are damaged or destroyed by trampling from livestock drawn to water sources, but grazing at appropriate times and stocking levels could also be beneficial by keeping vegetation cover more open (Knisley 2011).

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Acorn, J. 2001. Tiger beetles of Alberta: killers on the clay, stalkers on the sand. The University of Alberta Press, Edmonton, Alberta. 120 p.

Acorn, J. 2001. Tiger beetles of Alberta: killers on the clay, stalkers on the sand. The University of Alberta Press, Edmonton, Alberta. 120 p. Brust, M.L. and W.W. Hoback. 2009. Hypoxia tolerance in adult and larval Cicindela tiger beetles varies by life history but not habitat association. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 102(3):462-466.

Brust, M.L. and W.W. Hoback. 2009. Hypoxia tolerance in adult and larval Cicindela tiger beetles varies by life history but not habitat association. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 102(3):462-466. Brust, M.L., C.B. Knisley, S.M. Spomer, and K. Miwa. 2012b. Observations of oviposition behavior among North American tiger beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae) species and notes on mass rearing. The Coleopterists Bulletin 66(4):309-314.

Brust, M.L., C.B. Knisley, S.M. Spomer, and K. Miwa. 2012b. Observations of oviposition behavior among North American tiger beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae) species and notes on mass rearing. The Coleopterists Bulletin 66(4):309-314. Brust, M.L., W.W. Hoback, and N.W. Olson. 2004. Fish as predators of tiger beetles: white bass (Morone chrysops) eats Cicindela punctulata. Cicindela 36:23-25.

Brust, M.L., W.W. Hoback, and N.W. Olson. 2004. Fish as predators of tiger beetles: white bass (Morone chrysops) eats Cicindela punctulata. Cicindela 36:23-25. Carter, M. R. 1989. The biology and ecology of the tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Nebraska. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences XVII: 1-18.

Carter, M. R. 1989. The biology and ecology of the tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Nebraska. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences XVII: 1-18. Criddle, N. 1907. Habits of some Manitoba 'tiger beetles' (Cicindela). Canadian Entomologist 39:105-114.

Criddle, N. 1907. Habits of some Manitoba 'tiger beetles' (Cicindela). Canadian Entomologist 39:105-114. Gotschall, M.M., J.L. Bowley, R. Winton, K.A. Willemssens, B. Adams, L.G. Higley, and R.K.D. Peterson. 2021. County records of Cicindelidia punctulata (Olivier) (Coleoptera:Carabidae) in Idaho, USA. The Coleopterists Bulletin 75(4):812-814.

Gotschall, M.M., J.L. Bowley, R. Winton, K.A. Willemssens, B. Adams, L.G. Higley, and R.K.D. Peterson. 2021. County records of Cicindelidia punctulata (Olivier) (Coleoptera:Carabidae) in Idaho, USA. The Coleopterists Bulletin 75(4):812-814. Graves, R.C. and D.W. Brzoska. 1991. The tiger beetles of Ohio (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Bulletin of the Ohio Biological Survey New Series 8. 42 p.

Graves, R.C. and D.W. Brzoska. 1991. The tiger beetles of Ohio (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Bulletin of the Ohio Biological Survey New Series 8. 42 p. Hendricks, P. Personal tiger beetle observations.

Hendricks, P. Personal tiger beetle observations. Hooper, R.R. 1969. A review of Saskatchewan tiger beetles. Cicindela 1(4):1-5.

Hooper, R.R. 1969. A review of Saskatchewan tiger beetles. Cicindela 1(4):1-5. iNaturalist. Research-grade Observations. Accessed 5 November 2023. https://www.inaturalist.org/

iNaturalist. Research-grade Observations. Accessed 5 November 2023. https://www.inaturalist.org/ Kippenhan, Michael G. 1994. The Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Colorado. 1994. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 120(1):1-86.

Kippenhan, Michael G. 1994. The Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Colorado. 1994. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 120(1):1-86. Kirk, V.M. and E.U. Balsbaugh, Jr. 1975. A list of beetles of South Dakota. Brookings, SD: South Dakota State University. Agricultural Experiment Station, Technical Bulletin 42. 139 pages.

Kirk, V.M. and E.U. Balsbaugh, Jr. 1975. A list of beetles of South Dakota. Brookings, SD: South Dakota State University. Agricultural Experiment Station, Technical Bulletin 42. 139 pages. Knisley, C. B. 1979. Distribution, abundance, and seasonality of tiger beetles (Cicindelidae) in the Indiana Dunes region. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 88:209-217.

Knisley, C. B. 1979. Distribution, abundance, and seasonality of tiger beetles (Cicindelidae) in the Indiana Dunes region. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 88:209-217. Knisley, C.B. 1984. Ecological distribution of tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) in Colfax County, New Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist 29(1):93-104.

Knisley, C.B. 1984. Ecological distribution of tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) in Colfax County, New Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist 29(1):93-104. Knisley, C.B. 2011. Anthropogenic disturbances and rare tiger beetle habitats: benefits, risks, and implications for conservation. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 4:41-61.

Knisley, C.B. 2011. Anthropogenic disturbances and rare tiger beetle habitats: benefits, risks, and implications for conservation. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 4:41-61. Knisley, C.B., and T.D. Schultz. 1997. The biology of tiger beetles and a guide to the species of the south Atlantic states. Virginia Museum of Natural History Special Publication Number 5. 210 p.

Knisley, C.B., and T.D. Schultz. 1997. The biology of tiger beetles and a guide to the species of the south Atlantic states. Virginia Museum of Natural History Special Publication Number 5. 210 p. Knisley, C.B., M. Kippenhan, and D. Brzoska. 2014. Conservation status of United States tiger beetles. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 7:93-145.

Knisley, C.B., M. Kippenhan, and D. Brzoska. 2014. Conservation status of United States tiger beetles. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 7:93-145. Kohler, Nathan S. Excel spreadsheets of tiger beetle observations. 6 August 2022.

Kohler, Nathan S. Excel spreadsheets of tiger beetle observations. 6 August 2022. Kritsky, G. and J. Smith. 2005. Teddy's tigers: the Cicindelidae (Coleoptera) of Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota. Cicindela 37(1-2):1-16

Kritsky, G. and J. Smith. 2005. Teddy's tigers: the Cicindelidae (Coleoptera) of Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota. Cicindela 37(1-2):1-16 Larochelle, A and M Lariviere. 2001. Natural history of the tiger beetles of North America north of Mexico. Cicindela. 33:41-162.

Larochelle, A and M Lariviere. 2001. Natural history of the tiger beetles of North America north of Mexico. Cicindela. 33:41-162. Leonard, Jonathan G. and Ross T. Bell, 1999. Northeastern Tiger Beetles: a field guide to tiger beetles of New England and eastern Canada. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 176 p.

Leonard, Jonathan G. and Ross T. Bell, 1999. Northeastern Tiger Beetles: a field guide to tiger beetles of New England and eastern Canada. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 176 p. Mury Meyer, E.J. 1987. Asymmetric resource use in two syntopic species of larval tiger beetles (Cicindelidae). OIKOS 50:167-175.

Mury Meyer, E.J. 1987. Asymmetric resource use in two syntopic species of larval tiger beetles (Cicindelidae). OIKOS 50:167-175. Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, D.P. Duran, and C.J. Kazilek. 2015. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada, second edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 251 p.

Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, D.P. Duran, and C.J. Kazilek. 2015. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada, second edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 251 p. Shelford, V.E. 1908. Life-histories and larval habits of the tiger beetles (Cicindelidae). The Journal of the Linnean Society 30:157-184.

Shelford, V.E. 1908. Life-histories and larval habits of the tiger beetles (Cicindelidae). The Journal of the Linnean Society 30:157-184. Vaurie, P. 1950. Notes on the habitats of some North American tiger beetles. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 58(3):143-153.

Vaurie, P. 1950. Notes on the habitats of some North American tiger beetles. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 58(3):143-153. Wallis, J.B. 1961. The Cicindelidae of Canada. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press. 74 p.

Wallis, J.B. 1961. The Cicindelidae of Canada. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press. 74 p. Willis, H.L. 1966. Bionomics and zoogeography of the tiger beetles of saline habitats in the central United States (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Ph.D. Dissertation. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas. 312 p.

Willis, H.L. 1966. Bionomics and zoogeography of the tiger beetles of saline habitats in the central United States (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Ph.D. Dissertation. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas. 312 p. Winton, R.C. 2010. The effects of succession and disturbance on Coleopteran abundance and diversity in the Centennial Sandhills. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University. Bozeman, MT. 77pp + Appendices.

Winton, R.C. 2010. The effects of succession and disturbance on Coleopteran abundance and diversity in the Centennial Sandhills. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University. Bozeman, MT. 77pp + Appendices. Yager, D.D., A.P. Cook, D.L. Pearson, and H.G. Spangler. 2000. A comparative study of ultrasound-triggered behaviour in tiger beetles (Cicindelidae). Journal of Zoology 251:355-368.

Yager, D.D., A.P. Cook, D.L. Pearson, and H.G. Spangler. 2000. A comparative study of ultrasound-triggered behaviour in tiger beetles (Cicindelidae). Journal of Zoology 251:355-368.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Bousquet, Yves. 2012. Catalogue of Geadephaga (Coleoptera; Adephaga) of America north of Mexico. ZooKeys. 245:1-1722.

Bousquet, Yves. 2012. Catalogue of Geadephaga (Coleoptera; Adephaga) of America north of Mexico. ZooKeys. 245:1-1722. Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, and C.J. Kazilek. 2006. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada: identification, natural history, and distribution of the Cicindelidae. Oxford University Press, New York, New York. 227 pp.

Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, and C.J. Kazilek. 2006. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada: identification, natural history, and distribution of the Cicindelidae. Oxford University Press, New York, New York. 227 pp.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Punctured Tiger Beetle"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Insects"