View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Nevada Tiger Beetle - Ellipsoptera nevadica

Native Species

Global Rank:

G5

State Rank:

S5

Agency Status

USFWS:

USFS:

BLM:

External Links

General Description

The following is taken from Wallis (1961), Willis (1966), Kippenhan (1994), Acorn (2001), and Pearson et al (2015). The body length is 10-13 mm. Shiny dark brown, brown, reddish-brown, and rarely dark green or blue above. Three distinct pale maculations (complete) and connected with a marginal band along the outer edge of the elytra. Lacks a basal dot at the anterior corner of the shoulder maculation, thus the shoulder (humeral) maculation is “J” shaped, not “G” shaped. Elytra is distinctly widened in the middle, especially in females. Moderately iridescent blue-green to copper-green below. Forehead is hairy, with decumbent (lying flat) setae on forehead and body, labrum is short with one tooth. C. n. knausii, the only subspecies in Montana, is reddish-brown to brown above with moderately wide maculations, the base of the middle maculation connected broadly forward but narrowly to the rear with the marginal band.

Phenology

Tiger beetle life cycles fit two general categories based on adult activity periods. “Spring-fall” beetles emerge as adults in late summer and fall, then overwinter in burrows before emerging again in spring when mature and ready to mate and lay eggs. The life cycle may take 1-4 years. “Summer” beetles emerge as adults in early summer, then mate and lay eggs before dying. The life cycle may take 1-2 years, possibly longer depending on latitude and elevation (Kippenhan 1994, Knisley and Schultz 1997, and Leonard and Bell 1999). Adult Cicindela (= Ellipsoptera) nevadica is a summer species; for C. n. knausii, the subspecies occurring in Montana, typically late May to August (Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Pearson et al. 2015, and iNaturalist 2023). June to July in Colorado (Kippenhan 1994), June to August in Nebraska (Carter 1989), June to July in North Dakota (Kritsky and Smith 2005, and iNaturalist 2023) probably June to July or August in Alberta (Acorn 2001). No published information on phenology in Montana, but likely similar to Alberta, North Dakota, and Colorado.

Diagnostic Characteristics

The following comes from Wallis (1961), Willis (1966), Kippenhan (1994), Acorn (2001), and Pearson et al. (2015). The “J” shaped humeral maculation (lacking a basal dot) is diagnostic in our region. The

Hairy-necked Tiger Beetle (

Cicindela hirticollis) has a similar elytra pattern but with the humeral maculation “G” shaped (basal dot present), is larger, does not occur in saline habitats, and has upright hairs (setae) rather than flattened ones. Further analyses of maculation patterns, genitalia, and DNA may show that this species is comprised of three or four cryptic species (Pearson et al. 2015).

Species Range

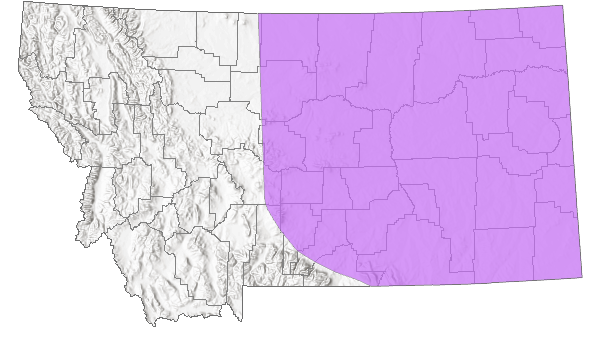

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

Cicindela (= Ellipsoptera) nevadica is present in contiguous areas of the prairie provinces of Canada (Alberta to Manitoba) south to Texas and New Mexico, with scattered populations in the desert southwest, in California, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona. The subspecies C. n. knausii, the most widespread of eight currently recognized subspecies and the only one present in Montana, is reported throughout the Great Plains, including the prairie regions of Montana as far west as Hill County in the north and Yellowstone County in the south (Willis 1966, and Pearson et al. 2015).

Migration

Non-migratory but capable of dispersal. When wings are fully developed (macropterous), it is a strong flier, fast runner, and has been observed wading through shallow water (Larochelle and Larivière 2001).

Habitat

Adult and larval tiger beetle habitat is essentially identical, the larvae live in soil burrows (Knisley and Schultz 1997). Across the range Cicindela (= Ellipsoptera) nevadica is associated with open ground of saline and non-saline flats, alkaline or sandy soils, wet muddy ground, ditches, saline margins of lakes, reservoirs, marshes, ponds, rivers, in grasslands and prairies always in presence of sparse vegetation and usually near water (Vaurie 1950, Willis 1966, Knisley 1984, Carter 1989, Kippenhan 1994, Acorn 2001, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Spomer 2004, Kritsky and Smith 2005, and Pearson et al. 2015). In Montana, habitat is poorly described but includes large moist alkali flats (Vaurie 1950).

Food Habits

Larval and adult tiger beetles are predaceous. In general, both feed considerably on ants (Wallis 1961, and Knisley and Schultz 1997). Adult and larval diet not described (Larochelle and Larivière 2001) but probably includes a variety of small insects and other invertebrates.

Ecology

Larval tiger beetles live in burrows and molt through three instars to pupation, which also occurs in the larval burrow. Adults make shallow burrows in soil for overnight protection, deeper burrows for overwintering. Adults are sensitive to heat and light and most active during sunny conditions. Excessive heat during midday on sunny days drives adults to seek shelter among vegetation or in burrows (Wallis 1961, and Knisley and Schultz 1997). Most subspecies of

Cicindela (= Ellipsoptera) nevadica, including

C. n. knausii, have a narrow range of ecological tolerance (stenotopic). Larval burrows excavated among sparse vegetation in vicinity of hummocks, along margins of small flats, and along sloping stream banks. Larvae can survive flooding (hypoxia) for more than 130 hours, adults for more than 15 hours (Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Brust and Hoback 2009). Adults are both diurnal and nocturnal, and gregarious. Seen going in and out of mud cracks on moist alkali flats, often stop to drink water on hot days. Attracted to artificial lights at night. Very wary, sometimes difficult to approach. When pursued makes frequent short flights. Predators apparently not described but probably include asilid (robber) flies, various birds, and bats.

C. nevadica are especially sensitive to ultrasound in the range of 25-50 kHz and makes nocturnal flights (Vaurie 1950, Yager et al. 2000, and Larochelle and Larivière 2001). Associated tiger beetle species across the range include

C. (=Eunota) circumpicta,

C. (=Ellipsoptera) cuprascens,

C. (=Ellipsoptera) fulgida,

C. (=Ellipsoptera) hamata,

C. (=Cicindelidia) hemorrhagica,

C. hirticollis,

C. (=Ellipsoptera) marutha,

C. (=Cicindelidia) nigrocoerulea,

C. (=Cicindelidia) pamphila,

C. (=Cicindelidia) punctulate,

C. repanda,

C. (=Ellipsoptera) sperata,

C. (=Eunota) togata, and

C. tranquebarica (Spomer and Higley 1993, Kippenhan 1994, Acorn 2001, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Spomer 2004, and Pearson et al. 2015).

Reproductive Characteristics

Life cycle of Cicindela (= Ellipsoptera) nevadica is probably 2 years. Overwinters as larvae (Acorn 2001). Pairs of C. n. knausii noted July to August in the north, late May to July farther south (Vaurie 1950, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, iNaturalist 2023). Adult females oviposit from the soil surface, depth of oviposition is not known. Larval burrows about 22-35 cm deep, duration of larval stage unknown but probably 2 years (Acorn 2001, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Brust et al. 2012, and Pearson et al. 2015). No information about reproductive characteristics in Montana.

Management

Not considered rare or in need of special conservation management (Knisley et al. 2014) except for four range-restricted subspecies, one of which is Federally Listed as Endangered. None of these occur in Montana, the closest to Montana is Cicindela (= Ellipsoptera) nevadica makosika in the Badlands of southwestern South Dakota (Spomer 2004). Maintaining areas of open saline soils, which is tied to fluctuations in surface and subsurface water levels, is probably of most importance to Cicindela nevadica in Montana. Intense irrigation, saline wetland drainage, or other forms of water diversion could reduce the water table at and near the surface and eliminate areas of suitable habitat especially needed by the larvae. Encroachment of open areas by native or exotic plants that invade saline soils might become a problem locally. Local disturbance could also be a problem for some populations where larval burrows are damaged or destroyed by trampling from livestock drawn to water sources, but grazing at appropriate times and stocking levels could also be beneficial by keeping vegetation cover more open (Knisley 2011).

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Acorn, J. 2001. Tiger beetles of Alberta: killers on the clay, stalkers on the sand. The University of Alberta Press, Edmonton, Alberta. 120 p.

Acorn, J. 2001. Tiger beetles of Alberta: killers on the clay, stalkers on the sand. The University of Alberta Press, Edmonton, Alberta. 120 p. Brust, M.L. and W.W. Hoback. 2009. Hypoxia tolerance in adult and larval Cicindela tiger beetles varies by life history but not habitat association. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 102(3):462-466.

Brust, M.L. and W.W. Hoback. 2009. Hypoxia tolerance in adult and larval Cicindela tiger beetles varies by life history but not habitat association. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 102(3):462-466. Brust, M.L., C.B. Knisley, S.M. Spomer, and K. Miwa. 2012b. Observations of oviposition behavior among North American tiger beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae) species and notes on mass rearing. The Coleopterists Bulletin 66(4):309-314.

Brust, M.L., C.B. Knisley, S.M. Spomer, and K. Miwa. 2012b. Observations of oviposition behavior among North American tiger beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae) species and notes on mass rearing. The Coleopterists Bulletin 66(4):309-314. Carter, M. R. 1989. The biology and ecology of the tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Nebraska. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences XVII: 1-18.

Carter, M. R. 1989. The biology and ecology of the tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Nebraska. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences XVII: 1-18. iNaturalist. Research-grade Observations. Accessed 5 November 2023. https://www.inaturalist.org/

iNaturalist. Research-grade Observations. Accessed 5 November 2023. https://www.inaturalist.org/ Kippenhan, Michael G. 1994. The Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Colorado. 1994. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 120(1):1-86.

Kippenhan, Michael G. 1994. The Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Colorado. 1994. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 120(1):1-86. Knisley, C.B. 1984. Ecological distribution of tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) in Colfax County, New Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist 29(1):93-104.

Knisley, C.B. 1984. Ecological distribution of tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) in Colfax County, New Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist 29(1):93-104. Knisley, C.B. 2011. Anthropogenic disturbances and rare tiger beetle habitats: benefits, risks, and implications for conservation. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 4:41-61.

Knisley, C.B. 2011. Anthropogenic disturbances and rare tiger beetle habitats: benefits, risks, and implications for conservation. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 4:41-61. Knisley, C.B., and T.D. Schultz. 1997. The biology of tiger beetles and a guide to the species of the south Atlantic states. Virginia Museum of Natural History Special Publication Number 5. 210 p.

Knisley, C.B., and T.D. Schultz. 1997. The biology of tiger beetles and a guide to the species of the south Atlantic states. Virginia Museum of Natural History Special Publication Number 5. 210 p. Knisley, C.B., M. Kippenhan, and D. Brzoska. 2014. Conservation status of United States tiger beetles. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 7:93-145.

Knisley, C.B., M. Kippenhan, and D. Brzoska. 2014. Conservation status of United States tiger beetles. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 7:93-145. Kritsky, G. and J. Smith. 2005. Teddy's tigers: the Cicindelidae (Coleoptera) of Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota. Cicindela 37(1-2):1-16

Kritsky, G. and J. Smith. 2005. Teddy's tigers: the Cicindelidae (Coleoptera) of Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota. Cicindela 37(1-2):1-16 Larochelle, A and M Lariviere. 2001. Natural history of the tiger beetles of North America north of Mexico. Cicindela. 33:41-162.

Larochelle, A and M Lariviere. 2001. Natural history of the tiger beetles of North America north of Mexico. Cicindela. 33:41-162. Leonard, Jonathan G. and Ross T. Bell, 1999. Northeastern Tiger Beetles: a field guide to tiger beetles of New England and eastern Canada. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 176 p.

Leonard, Jonathan G. and Ross T. Bell, 1999. Northeastern Tiger Beetles: a field guide to tiger beetles of New England and eastern Canada. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 176 p. Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, D.P. Duran, and C.J. Kazilek. 2015. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada, second edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 251 p.

Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, D.P. Duran, and C.J. Kazilek. 2015. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada, second edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 251 p. Spomer, S.M and L.G. Higley. 1993. Population status and distribution of the Salt Creek tiger beetle, Cicindela nevadica lincolniana Casey (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 66(4):392-398.

Spomer, S.M and L.G. Higley. 1993. Population status and distribution of the Salt Creek tiger beetle, Cicindela nevadica lincolniana Casey (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 66(4):392-398. Spomer, S.M. 2004. A new subspecies of Cicindela nevadica LeConte (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae) from the Badlands of South Dakota. The Coleopterists Bulletin 58(3):409-412.

Spomer, S.M. 2004. A new subspecies of Cicindela nevadica LeConte (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae) from the Badlands of South Dakota. The Coleopterists Bulletin 58(3):409-412. Vaurie, P. 1950. Notes on the habitats of some North American tiger beetles. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 58(3):143-153.

Vaurie, P. 1950. Notes on the habitats of some North American tiger beetles. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 58(3):143-153. Wallis, J.B. 1961. The Cicindelidae of Canada. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press. 74 p.

Wallis, J.B. 1961. The Cicindelidae of Canada. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press. 74 p. Willis, H.L. 1966. Bionomics and zoogeography of the tiger beetles of saline habitats in the central United States (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Ph.D. Dissertation. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas. 312 p.

Willis, H.L. 1966. Bionomics and zoogeography of the tiger beetles of saline habitats in the central United States (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Ph.D. Dissertation. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas. 312 p. Yager, D.D., A.P. Cook, D.L. Pearson, and H.G. Spangler. 2000. A comparative study of ultrasound-triggered behaviour in tiger beetles (Cicindelidae). Journal of Zoology 251:355-368.

Yager, D.D., A.P. Cook, D.L. Pearson, and H.G. Spangler. 2000. A comparative study of ultrasound-triggered behaviour in tiger beetles (Cicindelidae). Journal of Zoology 251:355-368.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Bousquet, Yves. 2012. Catalogue of Geadephaga (Coleoptera; Adephaga) of America north of Mexico. ZooKeys. 245:1-1722.

Bousquet, Yves. 2012. Catalogue of Geadephaga (Coleoptera; Adephaga) of America north of Mexico. ZooKeys. 245:1-1722. Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, and C.J. Kazilek. 2006. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada: identification, natural history, and distribution of the Cicindelidae. Oxford University Press, New York, New York. 227 pp.

Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, and C.J. Kazilek. 2006. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada: identification, natural history, and distribution of the Cicindelidae. Oxford University Press, New York, New York. 227 pp.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Nevada Tiger Beetle"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Insects"