View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Snapping Turtle - Chelydra serpentina

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is uncommon to rare within its native range across eastern Montana. No trend data are available, but habitat seems stable. It faces threats from road-based mortality and collecting and hunting, but the impact of these threats are poorly characterized and more study is needed.

General Description

EGGS:

Eggs are white and round. They range from 23-33 mm (0.91-1.3 in) in length, averaging 27-28 mm (1.06-1.1 in). The shell is leathery and is somewhat pliable. Clutch size ranges from 6-109 eggs (Werner et al. 2004).

HATCHLINGS:

Hatchings are dark brown to black with conspicuous ridges on their carapace. The carapace

measure 2.5-3.8 cm (1-1.5 inches) in length (Ernst et al. 1994, Werner et al. 2004).

JUVENILES AND ADULTS:

This species are large, stout turtles with an adult carapace length (CL) typically 20-35 cm (8-14 in), but grow larger in populations of the southern United States (Degenhardt et al. 1996). Adults usually weigh 4.5-16 kilograms (10-35 lbs). However, one Montana individual found in the Redwater River reached 32 lbs (14.5 kg) (Aderhold 1980) and another Montana specimen reportedly reached 48 lbs (21.8 kg) (Werner et al. 2004). Their tails are long about the length of the carapace (dorsal shell), with three rows of distinct sawtooth-shaped projections. The plastron (ventral shell) is brown with three keels that are more easily discerned in younger individuals. In older individuals, a good portion of the carapace is usually covered with algae. The cream-yellow plastron is greatly reduced compared to other turtles, and forms a cross-like shape. It has a large head with slightly hooked upper jaw. They have long necks with tubercles on the dorsal surface. They have webbed toes and powerful claws. The anal vent of the male usually extends past the posterior edge of the carapace, whereas it is found anterior to the rim in females. Males will usually grow larger than females (Hammerson 1999).

Diagnostic Characteristics

The Snapping Turtle is the only turtle in Montana with a reduced plastron covering less than half of the ventral surface, keeled scutes on the carapace, and a tail approximately as long as the carapace. There is no bright orange or yellow coloration as found on the Painted Turtle (

Chrysemys picta), and their carapace is hard, unlike the soft, leathery shell of the Spiny Softshell (

Apalone spinifera) (Black 1970c, Black and Black 1971, Werner et al. 2004).

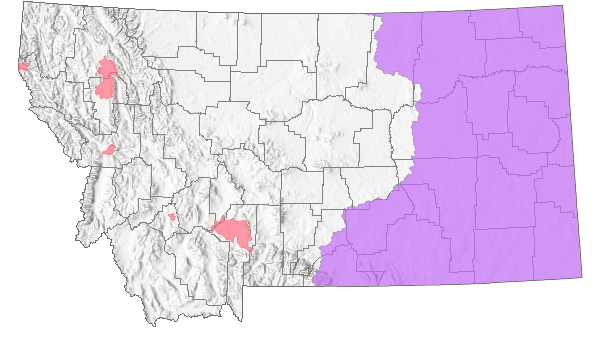

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Western Hemisphere Range

Western Hemisphere Range

Range Comments

The Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) ranges along the Atlantic Coast from Nova Scotia, Canada to Florida and westerly to the Rocky Mountain front, from southeastern Manitoba, Canada to Texas, and Mexico (Ernst et al. 1994). Two subspecies are recognized: the Florida Snapping Turtle (C. serpentina osceola) and the subspecies inhabiting Montana, the Eastern Snapping Turtle (C. serpentina serpentina) (Crother 2008).

In Montana, native populations are found from Carter County, west to Carbon and Stillwater Counties, and northeasterly to Phillips County (MTNHP 2022). Most records are from the southeastern portion of the state in the Yellowstone River system and tributaries, especially along the Tongue River drainage. Currently, there are no confirmed Montana records from the Missouri River or its tributaries above the dam on Fort Peck Lake. Introduced animals have been detected in several counties in western Montana and control efforts are ongoing (Maxell et al. 2003, MTNHP 2022). Detections in these areas should be reported to Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks.

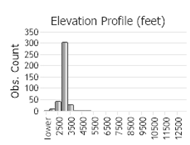

Maximum elevation: 1,403 m (4603 ft) in Gallatin County (Scott Barndt; MTNHP 2022).

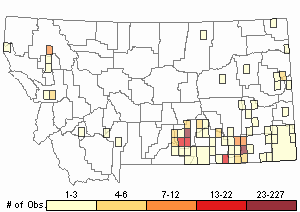

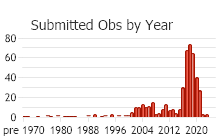

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 502

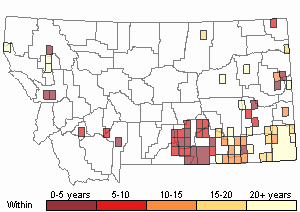

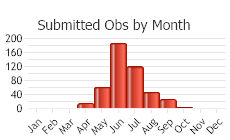

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

No specific migratory information for Montana is currently available.

Research from other locations indicates that the Snapping Turtle may migrate up to several miles between the water bodies and nesting areas. Evidence suggests that adults may use the sun as a navigational guide during overland migrations (Ernst et al. 1994). Some may travel a few kilometers between summer range and winter hibernation sites, while others overwinter within their summer range (Brown and Brooks 1994). In Ontario, the distances traveled to nesting sites ranged from 370 to 2020 m (1,214 to 6,627 ft) and a mean of 1,053 m (3,455 ft), and movements were greatest from spring to mid-July (Pettit et al. 1995). Distances traveled by C. serpentina in South Dakota ranged from 0 to 6.05 km (3.76 mi) but averaged just 1.1 km (0.68 mi) (Hammer 1969).

Habitat

Habitats used in Montana are probably similar to other areas in their range, but local studies are lacking and there is little qualitative information available. They have been captured or observed in backwaters along major rivers, at smaller reservoirs, and in smaller streams and creeks with permanent flowing water and sandy or muddy bottoms (Reichel 1995b, Hendricks and Reichel 1996b, Gates 2005, Paul Hendricks, personal observation). They have also been observed in temporary pools along small intermittent streams near Decker, Montana (M. Gates, personal observation). Nesting habitat and nest sites have not been described.

Freshwater habitats with a soft mud bottom and cover such as abundant aquatic vegetation or submerged brush and logs are preferred (Hammerson 1999) and brackish water in some areas. Although found most often in shallower water, an Ontario, Canada individual was observed by R. J. Brooks regularly diving 10 m (33 ft) to the bottom of a lake (Ernst et al. 1994). Temporary ponds and reservoirs may also be occupied. Hatchlings and juveniles tend to occupy shallower sites than mature individuals in the same water bodies. They are mostly bottom dwellers, where they spend much of their time. Although highly aquatic, they may make long movements overland if their pond or marsh dries (Baxter and Stone 1985, Ernest et al. 1994, Hammerson 1999). Snapping Turtles have a high-water loss gradient (0.64 g/hour or 0.02 oz/hour); therefore, they are at risk out of water in warm or dry conditions and rarely bask out of water. Aerial basking is more common in cooler environments in the northern portions of their range (Ernst et al. 1994) and has been observed on the Tongue River of southeastern Montana (Matt Gates, personal observation). They hibernate singly or in groups in streams, lakes, ponds, or marshes; in bottom mud, in or under submerged logs or debris, under an overhanging bank, or in Muskrat (

Ondatra zibethicus spp.) tunnels; often in shallow water; sometimes in anoxic sites (Brown and Brooks 1994).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Wetland and Riparian

Alkaline - Saline Wetlands

Peatland

Riparian and Wetland Forest

Riparian Shrubland

Wet Meadow and Marsh

Recently Disturbed or Modified

Introduced Vegetation

Food Habits

The diets of Snapping Turtle have not been studied in Montana, but they are known to eat about anything that can be captured while foraging in the water. They eat many kinds of vertebrates (fish, amphibians, reptiles, aquatic birds, and small mammals), invertebrates (insects, spiders, crustaceans, mollusks, leeches, and sponges), various plants and algae, and carrion (Pell 1940, Ernst et al. 1994). Their diet appears to be dependent on availability. In New York and Massachusetts, specimens collected from marshy lakes consumed 90% plant material, but individuals from small streams consumed 100% crayfish (Pell 1940). The young often search actively for food, but adults generally lie in ambush to seize their prey (Ernst et al. 1994). This species is known to eat nine orders of insects (ants, beetles, and moths the most abundant), and spiders, scorpions, ticks, and mites have been reported in the diet (Hammerson 1999).

Ecology

Snapping Turtles are known to hibernate independently or in groups. They overwinter in lakes, ponds, streams, or marshes; in bottom mud, in or under submerged logs or debris, under overhanging banks, in muskrat tunnels, or in the saturated soil of pastures (Meeks and Ultsch 1990). They sometimes overwinter in shallow, anoxic water but survivorship is higher in normoxic condition. Underwater winter movements are not uncommon. In Ontario,

C. serpentina emerged from winter dormancy when water reached about 7.5 °C (45.5 °F) (Obbard and Brooks 1981b, Meeks and Ultsch 1990, Brown and Brooks 1994).

Populations can vary greatly regionally, locally, and temporally (Froese and Burghardt 1975); therefore, population data from other locations cannot be extrapolated to Montana with any accuracy. In Ontario, males occupied relatively stable, overlapping home ranges; with summer ranges between 0.4 to 2.3 hectares (Galbraith et al. 1987). Also in Ontario, the foraging home ranges documented for a year at three sites during July to August were 2.3 to 18.1 hectares (means fell between 5 and 9 hectares). The home range length was about 550 to 1,990 m (1,804 to 6,529 ft); however, home range size did not vary with habitat productivity (Brown et al. 1994). In another Ontario study, home range size over a year was 1.0 to 28.4 hectares, averaging about 9 hectares for females and about 2 to 3 hectares for males (Pettit et al. 1995). Densities in marshes of South Dakota reached one per 2 acres (Hammer 1969).

Egg survival is usually low, not more than 0.22, and adult survival generally high, over 0.90. A population in Ontario, was characterized as stable, with adult female annual survivorship greater than 0.95. Later, a great increase in adult mortality occurred, apparently due primarily to Northern River Otter (

Lontra canadensis) predation on hibernating turtles, resulting in no compensatory density-dependent response in reproduction and recruitment (Brooks et al. 1991, Iverson 1991). In Michigan, actual annual survivorship of juveniles was over 0.65 by age 2 and averaged 0.77 between ages 2 and 12 years. Annual survivorship of adult females ranged from 0.88 to 0.97. Population stability was most sensitive to changes in adult or juvenile survival and less sensitive to changes in age at sexual maturity, nest survival, or fecundity (Congdon et al. 1994). In South Dakota, Hammer (1969) reported that predators destroyed 59% of nests, and that emergence in undisturbed nests was less than 20%. Snapping Turtles may have limited range in the north because of overwintering mortality (Obbard and Brooks 1981b). Snapping Turtles are relatively long-lived. In an Ontario population, females have an average lifespan of 40 years (Galbraith and Brooks 1989), and average lifespan of a South Carolina population was 28 years (Ernst et al 1994). The record for a captive individual is 47 years (Werner et al. 2004).

Snapping Turtles frequently incur high rates of nest predation by various animals, particularly skunks, Raccoon (

Procyon lotor), foxes, American Black Bear (

Ursus americanus), American Crow (

Corvus brachyrhynchos), and snakes (Congdon et al. 1987, Ernst et al. 1994, Hammerson 1999). In Michigan, eggs and young typically incur 60-100% predation, primarily by Raccoons (Harding 1997). Temple (1987) suggest that nest predation increases near habitat edges. Raccoons, Coyote (

Canis latrans), Northern River Otter, American Black Bear, and often humans will prey on adults. Herons, bitterns, hawks, eagles, various predatory fish, and American Bullfrog (

Lithobates catesbeianus) prey on hatchlings and juveniles (Ernst et al. 1994). Compared with other species,

C. serpentina, uses very aggressive display postures to thwart potential predators, such as facing its attacker and lifting its legs in various positions while gaping its mouth. (Dodd et al. 1975). Snapping Turtles are often parasitized by leaches (

Placobdella spp.) and a protozoan blood parasite (

Haemogregarina balli). An Ontario individual reportedly had 768 leaches attached (Brooks et al. 1990). Despite high rates of infestation, Brown and Brooks (1994) found that these parasites do not negatively affect reproductive output. Humans are the only recorded predators in Montana (Paul Hendricks, personal observation).

Reproductive Characteristics

In Iowa, males can reach sexual maturity by their fifth year and females as early as their seventh (Christiansen and Burken 1979). However, in some populations, maturity is not reached before 15 years. The youngest mature female known from Michigan was 12 years. In Ontario the average age of first nesting ranged from 17-19 years. Virtually no reproductive data exists specific to Montana. However, Montana populations likely exhibit traits similar to those elsewhere. Warming temperatures trigger nesting behavior in females. Obbard and Brooks (1987) developed a model to predict the onset of nesting activity from temperature data in Ontario. Females may travel several kilometers to locate a suitable nest site. Obbard and Brooks (1980) reported a round trip distance of 16 km (9.94 mi) to a nest site and back (Ernst et al. 1994).

Nests are usually built in open areas a hundred meters or more from water; excavated in soft sand, loam, vegetation debris, sawdust piles, and Beaver (

Castor canadensis) and Muskrat lodges. Females generally dig nests from 7-18 cm (2.76-7.09 in) (Congdon et al. 1987, Ernst et al. 1994, Hammerson 1999). In northern regions, eggs are generally deposited in late May to early June. Recorded clutch sizes range from 6 to 104, but typically 20-40 eggs are laid. Clutch size tends to increase from southerly to northerly latitudes. Eggs incubate for 55-125 days (usually 75-95) before hatching, with incubation period increasing with latitude. The sex of each hatchling is determined by each egg’s temperature during a critical developmental period, known as temperature dependent sex determination. Relatively cooler temperatures produce females and warmer temperatures produce males. The sex ratio of hatchlings is commonly 1:1 (Ernst et al. 1994). Nest site selection is critical for survival of hatchlings. Eggs buried in moister substrate generally support better embryonic development and larger hatchlings, compared to eggs in drier environments (Morris et al. 1983). The incubation environment of eggs can later effect growth and viability of young Snapping Turtles (McKnight and Gutzke (1993). Bobyn and Brooks (1994) suggest incubation temperature and moisture limit the northern distribution of

C. serpentina.

Management

The following was taken from the Status and Conservation section for the Snapping Turtle account in

Maxell et al. 2009Although this species is common in many parts of its range, it is rare in Montana, having been recorded in only a few watersheds of southeastern Montana. Due to this restricted range and the lack of information this species in Montana, it is considered a state species of concern, and is listed as sensitive by the Bureau of Land Management. Studies identifying or addressing specific risk factors for

C. serpentina in Montana are lacking. However, documented studies and other issues pertaining to their conservation include the following: (1) Roads often have negative impacts on population size and distribution of reptiles, and particularly turtles. High road density has been positively correlated to low population size. This has led to absence of species in road-developed areas and lead to local extirpations. (Rudolph et al. 1998, Jochimsen et al. 2004).

C. serpentina females often migrate over a kilometer to reach suitable nesting sites (Obbard and Brooks 1981a), which makes them particularly vulnerable to roadkill. During a three-year study in Ontario, Haxton (2000) noted that 30.5% of all turtles observed were killed on roads. (2) Snapping Turtles, particularly in northern populations take over 15 years to attain sexual maturity, have extended reproductive lifespans, high natural adult survival rates, and extended longevity. Egg and hatchling mortality is also often very high attributing to a low annual reproductive potential. These life history traits are typical of long-lived species vulnerable to adult mortality. Minimum levels of natural (e.g., winter kill) or human-caused mortality to mature adults can have serious negative impacts to populations. Due to this low reproductive potential, seriously diminished populations can take years to recover (Brooks et al. 1988, Brooks et al. 1991, Congdon et al. 1994, Congdon et al. 1995). (3) Snapping Turtles are a long-lived bottom dweller that can store environmental contaminants in their body fat, muscle tissue, liver, and eggs making them particularly susceptible to bioaccumulation. They often carry high concentrations of organochlorine contaminants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) (Brooks et al. 1988, Harding 1997). (4) Popular for meat and soup dishes,

C. serpentina are managed as game animals in many states. Due to their low reproductive potential, overharvesting can decimate local populations, which can take years to recover (Brooks et al. 1988). Harvesting of adults is more detrimental to long-term population viability than high levels of egg and hatchling mortality, which normally occur. Human harvesting of

C. serpentina in Montana is not well documented but may occur where they are abundant. (5) Dams and large reservoirs on rivers (e.g., Fort Peck Dam and Reservoir) may inhibit population continuity to some degree, judging by the apparent lack of viable populations on the Missouri River in Montana (Maxell et al. 2003). However, there is no quantitative data to verify this. Snapping Turtles will travel large distances overland and therefore may be able to bypass some dams.

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Aderhold, M. 1980. The 32-pound snapper of Redwater River. Montana Outdoors 11(4): 9-10.

Aderhold, M. 1980. The 32-pound snapper of Redwater River. Montana Outdoors 11(4): 9-10. Baxter, G.T. and M.D. Stone. 1985. Amphibians and reptiles of Wyoming. Second edition. Wyoming Game and Fish Department. Cheyenne, WY. 137 p.

Baxter, G.T. and M.D. Stone. 1985. Amphibians and reptiles of Wyoming. Second edition. Wyoming Game and Fish Department. Cheyenne, WY. 137 p. Black, J.H. 1970c. Turtles of Montana. Montana Wildlife, Montana Fish and Game Commission. Animals of Montana Series. 1970(Fall): 26-31.

Black, J.H. 1970c. Turtles of Montana. Montana Wildlife, Montana Fish and Game Commission. Animals of Montana Series. 1970(Fall): 26-31. Black, J.H. and J.N. Black. 1971. Montana and its turtles. International Turtle and Tortoise Society 1971(May-July): 10-11, 34-35.

Black, J.H. and J.N. Black. 1971. Montana and its turtles. International Turtle and Tortoise Society 1971(May-July): 10-11, 34-35. Bobyn, M.L. and R.J. Brooks. 1994. Incubation conditions as potential factors limiting the northern distribution of snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina. Canadian Journal of Zoology 72(1): 28-37.

Bobyn, M.L. and R.J. Brooks. 1994. Incubation conditions as potential factors limiting the northern distribution of snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina. Canadian Journal of Zoology 72(1): 28-37. Brooks, R. J., D. A Galbraith, E. G. Nancekivell, and C. A. Bishop. 1988. Developing management guidelines for snapping turtles. In: R.C. Szaro, K.E. Severson, and D.R. Patton, technical coordinators. pp. 174-179. Management of amphibians, reptiles, and small mammals in North America. General Technical Report RM-166. U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Brooks, R. J., D. A Galbraith, E. G. Nancekivell, and C. A. Bishop. 1988. Developing management guidelines for snapping turtles. In: R.C. Szaro, K.E. Severson, and D.R. Patton, technical coordinators. pp. 174-179. Management of amphibians, reptiles, and small mammals in North America. General Technical Report RM-166. U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins, Colorado. Brooks, R. J., G. P. Brown, and D. A. Galbraith. 1991. Effects of a sudden increase in natural mortality of adults on a population of the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 69: 1314-1320.

Brooks, R. J., G. P. Brown, and D. A. Galbraith. 1991. Effects of a sudden increase in natural mortality of adults on a population of the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 69: 1314-1320. Brooks, R.J., D.A. Galbraith, and J.A. Layfield. 1990. Occurrence of Placobdella parasitica (Hirudinea) on snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina, in southeastern Ontario. Journal of Parasitology 76(2): 190-195.

Brooks, R.J., D.A. Galbraith, and J.A. Layfield. 1990. Occurrence of Placobdella parasitica (Hirudinea) on snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina, in southeastern Ontario. Journal of Parasitology 76(2): 190-195. Brown, G. P. and R. J. Brooks. 1994. Characteristics of and fidelity to hibernacula in a northern population of snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina. Copeia 1: 222-226.

Brown, G. P. and R. J. Brooks. 1994. Characteristics of and fidelity to hibernacula in a northern population of snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina. Copeia 1: 222-226. Brown, G.P., C.A. Bishop, and R.J. Brooks. 1994. Growth rate, reproductive output, and temperature selection of snapping turtles in habitats of different productivities. Journal of Herpetology 28(4): 405-410.

Brown, G.P., C.A. Bishop, and R.J. Brooks. 1994. Growth rate, reproductive output, and temperature selection of snapping turtles in habitats of different productivities. Journal of Herpetology 28(4): 405-410. Christiansen, J.L. and R.R. Burken. 1979. Growth and maturity of the snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) in Iowa. Herpetologica 35: 261-266.

Christiansen, J.L. and R.R. Burken. 1979. Growth and maturity of the snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) in Iowa. Herpetologica 35: 261-266. Congdon, J .D., A. E. Dunham and R. C. Van Loben Sels. 1994. Demographics of common snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina): implications for conservation and management of long-lived organisms. American Zoologist 34: 397-408.

Congdon, J .D., A. E. Dunham and R. C. Van Loben Sels. 1994. Demographics of common snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina): implications for conservation and management of long-lived organisms. American Zoologist 34: 397-408. Congdon, J. D., G. L. Breitenbach, R. C. Van Loben Sels, and D. W. Tinkle. 1987. Reproduction and nesting ecology of snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) in southeastern Michigan (USA). Herpetologica 43(1): 39-54.

Congdon, J. D., G. L. Breitenbach, R. C. Van Loben Sels, and D. W. Tinkle. 1987. Reproduction and nesting ecology of snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) in southeastern Michigan (USA). Herpetologica 43(1): 39-54. Congdon, J.D., A.E. Dunham, R.C. van Loben Sels, and J.T. Austin. 1995. Life histories and demographics of long-lived organisms: implications for management and conservation. U.S.F.S. General Technical Report. RM 264: 624-630.

Congdon, J.D., A.E. Dunham, R.C. van Loben Sels, and J.T. Austin. 1995. Life histories and demographics of long-lived organisms: implications for management and conservation. U.S.F.S. General Technical Report. RM 264: 624-630. Crother, B.I. (ed.) 2008. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico. SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 37:1-84.

Crother, B.I. (ed.) 2008. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico. SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 37:1-84. Degenhardt, W. G., C. W. Painter, and A. H. Price. 1996. Amphibians and reptiles of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Degenhardt, W. G., C. W. Painter, and A. H. Price. 1996. Amphibians and reptiles of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. Dodd, C.K., Jr. and E.D. Brodie, Jr. 1975. Notes on the defensive behavior of the snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. Herpetologica 31: 286-288.

Dodd, C.K., Jr. and E.D. Brodie, Jr. 1975. Notes on the defensive behavior of the snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. Herpetologica 31: 286-288. Ernst, C. H., R. W. Barbour, and J. E. Lovich. 1994. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D.C. 578 p.

Ernst, C. H., R. W. Barbour, and J. E. Lovich. 1994. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D.C. 578 p. Froese, A. D. and G. M. Burghardt. 1975. A dense natural population of the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Herpetologica 31:204-208.

Froese, A. D. and G. M. Burghardt. 1975. A dense natural population of the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Herpetologica 31:204-208. Galbraith, D. A., M. W. Chandler, and R. J. Brooks. 1987. The fine structure of home ranges of male Chelydra serpentina: are snapping turtles territorial? Canadian Journal of Zoology 65(11): 2623-2629.

Galbraith, D. A., M. W. Chandler, and R. J. Brooks. 1987. The fine structure of home ranges of male Chelydra serpentina: are snapping turtles territorial? Canadian Journal of Zoology 65(11): 2623-2629. Galbraith, D.A. and R.J. Brooks. 1989. Age estimates for snapping turtles. Journal of Wildlife Management 53(2): 502-508.

Galbraith, D.A. and R.J. Brooks. 1989. Age estimates for snapping turtles. Journal of Wildlife Management 53(2): 502-508. Gates, M.T. 2005. Amphibian and reptile baseline survey: CX field study area Bighorn County, Montana. Report to Billings and Miles City Field Offices of Bureau of Land Management. Maxim Technologies, Billings, MT. 28pp + Appendices.

Gates, M.T. 2005. Amphibian and reptile baseline survey: CX field study area Bighorn County, Montana. Report to Billings and Miles City Field Offices of Bureau of Land Management. Maxim Technologies, Billings, MT. 28pp + Appendices. Hammer, D. A. 1969. Parameters of a marsh snapping turtle population, Lacreek Refuge, South Dakota. Journal of Wildlife Management 33(4):995-1005.

Hammer, D. A. 1969. Parameters of a marsh snapping turtle population, Lacreek Refuge, South Dakota. Journal of Wildlife Management 33(4):995-1005. Hammerson, G.A. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. University Press of Colorado & Colorado Division of Wildlife. Denver, CO. 484 p.

Hammerson, G.A. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. University Press of Colorado & Colorado Division of Wildlife. Denver, CO. 484 p. Harding, J. H. 1997. Amphibians and reptiles of the Great Lakes region. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. xvi + 378 pp.

Harding, J. H. 1997. Amphibians and reptiles of the Great Lakes region. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. xvi + 378 pp. Haxton, T. 2000. Road mortality of snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina, in central Ontario during their nesting period. The Canadian Field Naturalist 114(1): 106.

Haxton, T. 2000. Road mortality of snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina, in central Ontario during their nesting period. The Canadian Field Naturalist 114(1): 106. Hendricks, P. and J.D. Reichel. 1996b. Preliminary amphibian and reptile survey of the Ashland District, Custer National Forest: 1995. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 79 p.

Hendricks, P. and J.D. Reichel. 1996b. Preliminary amphibian and reptile survey of the Ashland District, Custer National Forest: 1995. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 79 p. Iverson, J.B. 1991. Patterns of survivorship in turtles (order Testudines). Canadian Journal of Zoology 69: 385-391.

Iverson, J.B. 1991. Patterns of survivorship in turtles (order Testudines). Canadian Journal of Zoology 69: 385-391. Jochimsen, D.M., C.R. Peterson, K.M. Andrews, and J.W. Gibbons. 2004. A literature review of the effects of roads on amphibians and reptiles and the measures used to minimize those effects. Final Draft, Idaho Fish and Game Department, USDA Forest Service.

Jochimsen, D.M., C.R. Peterson, K.M. Andrews, and J.W. Gibbons. 2004. A literature review of the effects of roads on amphibians and reptiles and the measures used to minimize those effects. Final Draft, Idaho Fish and Game Department, USDA Forest Service. Maxell, B.A., J.K. Werner, P. Hendricks, and D.L. Flath. 2003. Herpetology in Montana: a history, status summary, checklists, dichotomous keys, accounts for native, potentially native, and exotic species, and indexed bibliography. Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology, Northwest Fauna Number 5. Olympia, WA. 135 p.

Maxell, B.A., J.K. Werner, P. Hendricks, and D.L. Flath. 2003. Herpetology in Montana: a history, status summary, checklists, dichotomous keys, accounts for native, potentially native, and exotic species, and indexed bibliography. Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology, Northwest Fauna Number 5. Olympia, WA. 135 p. Maxell, B.A., P. Hendricks, M.T. Gates, and S. Lenard. 2009. Montana amphibian and reptile status assessment, literature review, and conservation plan, June 2009. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 643 p.

Maxell, B.A., P. Hendricks, M.T. Gates, and S. Lenard. 2009. Montana amphibian and reptile status assessment, literature review, and conservation plan, June 2009. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 643 p. McKnight, C.M. and W.H.N. Gutzke. 1993. Effects of the embryonic environment and of hatchling housing conditions on growth of young snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Copeia (2): 475-482.

McKnight, C.M. and W.H.N. Gutzke. 1993. Effects of the embryonic environment and of hatchling housing conditions on growth of young snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Copeia (2): 475-482. Meeks, R.L. and G.R. Ultsch. 1990. Overwintering behavior of snapping turtles. Copeia 1990(3): 880-884.

Meeks, R.L. and G.R. Ultsch. 1990. Overwintering behavior of snapping turtles. Copeia 1990(3): 880-884. Morris, K.A., G.C. Packard, T.J. Boardman, G.L. Paukstis, and M.J. Packard. 1983. Effect of the hydric environment on growth of embryonic snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Herpetologica 39: 272-285.

Morris, K.A., G.C. Packard, T.J. Boardman, G.L. Paukstis, and M.J. Packard. 1983. Effect of the hydric environment on growth of embryonic snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Herpetologica 39: 272-285. Obbard, M.E. and R.J. Brooks. 1980. Nesting migrations of the snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Herpetologica 36: 158-162.

Obbard, M.E. and R.J. Brooks. 1980. Nesting migrations of the snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Herpetologica 36: 158-162. Obbard, M.E. and R.J. Brooks. 1981a. A radio-telemetry and mark-recapture study of activity in the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. Copeia 1981: 630-637.

Obbard, M.E. and R.J. Brooks. 1981a. A radio-telemetry and mark-recapture study of activity in the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. Copeia 1981: 630-637. Obbard, M.E. and R.J. Brooks. 1981b. Fate of overwintered clutches of the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) in Algonquin Park, Ontario, Canada. Canadian Field Naturalist 95:350-352.

Obbard, M.E. and R.J. Brooks. 1981b. Fate of overwintered clutches of the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) in Algonquin Park, Ontario, Canada. Canadian Field Naturalist 95:350-352. Obbard, M.E. and R.J. Brooks. 1987. Prediction of the onset of the annual nesting season of the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. Herpetologica 43: 324-328.

Obbard, M.E. and R.J. Brooks. 1987. Prediction of the onset of the annual nesting season of the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. Herpetologica 43: 324-328. Pell, S.M. 1940. Notes on the food habits of the common snapping turtle. Copeia 1940: 131.

Pell, S.M. 1940. Notes on the food habits of the common snapping turtle. Copeia 1940: 131. Pettit, K. E., C. A. Bishop, and R. J. Brooks. 1995. Home range and movements of the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina serpentina, in a coastal wetland of Hamilton Harbour, Lake Ontario, Canada. Canadian Field Naturalist 109(2): 192-200.

Pettit, K. E., C. A. Bishop, and R. J. Brooks. 1995. Home range and movements of the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina serpentina, in a coastal wetland of Hamilton Harbour, Lake Ontario, Canada. Canadian Field Naturalist 109(2): 192-200. Reichel, J.D. 1995b. Preliminary amphibian and reptile survey of the Sioux District of the Custer National Forest: 1994. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 75 p.

Reichel, J.D. 1995b. Preliminary amphibian and reptile survey of the Sioux District of the Custer National Forest: 1994. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 75 p. Rudolph, D.C., S.J. Burdorf, R.N. Conner, and J.G. Dickson. 1998. The impact of roads on the timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus), in Eastern Texas. pp. 236-240. In: G.L. Evink, P. Garrett, D. Zeigler, and J. Berry (eds). Proceedings of the international conference on wildlife ecology.

Rudolph, D.C., S.J. Burdorf, R.N. Conner, and J.G. Dickson. 1998. The impact of roads on the timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus), in Eastern Texas. pp. 236-240. In: G.L. Evink, P. Garrett, D. Zeigler, and J. Berry (eds). Proceedings of the international conference on wildlife ecology. Temple, S.A. 1987. Predation on turtle nests increases near ecological edges. Copeia 1987(1): 250-252.

Temple, S.A. 1987. Predation on turtle nests increases near ecological edges. Copeia 1987(1): 250-252. Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks and D.L. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and Reptiles of Montana. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, MT. 262 pp.

Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks and D.L. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and Reptiles of Montana. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, MT. 262 pp.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? [DCC] Decker Coal Company. 1998. 1997 Consolidated annual progress report. Decker Coal Company West, North and East Pits. Decker, MT.

[DCC] Decker Coal Company. 1998. 1997 Consolidated annual progress report. Decker Coal Company West, North and East Pits. Decker, MT. [OEA] Olson Elliot and Associates Research. 1985. 1983-1984 Wildlife monitoring report for the CX Ranch project. Olson Elliot and Associates Research. Helena, MT.

[OEA] Olson Elliot and Associates Research. 1985. 1983-1984 Wildlife monitoring report for the CX Ranch project. Olson Elliot and Associates Research. Helena, MT. [VTNWI] VTN Wyoming Incorporated. No Date. Second year's analysis of terrestrial wildlife on proposed mine access and railroad routes in southern Montana and northern Wyoming, March 1979 - February 1980. VTN Wyoming Incorporated. Sheridan, WY. 62 p.

[VTNWI] VTN Wyoming Incorporated. No Date. Second year's analysis of terrestrial wildlife on proposed mine access and railroad routes in southern Montana and northern Wyoming, March 1979 - February 1980. VTN Wyoming Incorporated. Sheridan, WY. 62 p. [WESTECH] Western Technology and Engineering Incorporated. 1998. Wildlife Monitoring Absaloka Mine Area 1997. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc., Helena, Mt.

[WESTECH] Western Technology and Engineering Incorporated. 1998. Wildlife Monitoring Absaloka Mine Area 1997. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc., Helena, Mt. Abel, B. 1992. Snapping turtle attacks on trumpeter swan cygnets in Wisconsin. Passenger Pigeon 54(3): 209-213.

Abel, B. 1992. Snapping turtle attacks on trumpeter swan cygnets in Wisconsin. Passenger Pigeon 54(3): 209-213. Albers, P.H., L. Sileo, and B.M. Mulhem. 1986. Effects of environmental contaminants on snapping turtles of a tidal wetland. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 15(1): 39-49.

Albers, P.H., L. Sileo, and B.M. Mulhem. 1986. Effects of environmental contaminants on snapping turtles of a tidal wetland. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 15(1): 39-49. Anderson, J.T. and A.M. Anderson. 1996. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (common snapping turtle). Herpetological Review 27(3): 150.

Anderson, J.T. and A.M. Anderson. 1996. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (common snapping turtle). Herpetological Review 27(3): 150. Applegate, R.D., R.C. Spencer, and F.M. Trasko. 1995. Extensions to the known range for three Maine reptiles. Canadian Field Naturalist 109(4): 444-446.

Applegate, R.D., R.C. Spencer, and F.M. Trasko. 1995. Extensions to the known range for three Maine reptiles. Canadian Field Naturalist 109(4): 444-446. Asch, R.P. 1951. A preliminary report on the size, egg number, incubation period, and hatching in the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. Virginia Academy of Science 29: 312.

Asch, R.P. 1951. A preliminary report on the size, egg number, incubation period, and hatching in the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. Virginia Academy of Science 29: 312. Ashley, E.P., and J.T. Robinson. 1996. Road mortality of amphibians, reptiles and other wildlife on the Long Point causeway, Lake Erie, Ontario. Canadian Field Naturalist 110: 403-412.

Ashley, E.P., and J.T. Robinson. 1996. Road mortality of amphibians, reptiles and other wildlife on the Long Point causeway, Lake Erie, Ontario. Canadian Field Naturalist 110: 403-412. Association for the Study of Reptilia and Amphibia. 1996. Revenge of the ninja turtles. Rephiberary 228:9.

Association for the Study of Reptilia and Amphibia. 1996. Revenge of the ninja turtles. Rephiberary 228:9. Atkinson, E.C. and M.L. Atkinson. 2004. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Ashland and Sioux of the Custer National Forest with special emphasis on the Three-Mile Stewardship Area:2002. Marmot's Edge Conservation. 22 p.

Atkinson, E.C. and M.L. Atkinson. 2004. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Ashland and Sioux of the Custer National Forest with special emphasis on the Three-Mile Stewardship Area:2002. Marmot's Edge Conservation. 22 p. Avery, H.W. and L.J. Vitt. 1984. How to get blood from a turtle. Copeia 1984: 209-210.

Avery, H.W. and L.J. Vitt. 1984. How to get blood from a turtle. Copeia 1984: 209-210. Baker, M.R. 1986. Falcaustra sp. (Nematoda: Kathlaniidae) parasitic in turtles and frogs in Ontario (Canada). Canadian Journal of Zoology 64(1): 228-237.

Baker, M.R. 1986. Falcaustra sp. (Nematoda: Kathlaniidae) parasitic in turtles and frogs in Ontario (Canada). Canadian Journal of Zoology 64(1): 228-237. Baldwin, F.M. 1925b. The relation of body to environmental temperature in turtles, Chrysemys marginata belli (Gray) and Chelydra serpentina (Linn.). Biology Bulletin 48: 432-445.

Baldwin, F.M. 1925b. The relation of body to environmental temperature in turtles, Chrysemys marginata belli (Gray) and Chelydra serpentina (Linn.). Biology Bulletin 48: 432-445. Bickham, J.W. and J.L. Carr. 1983. Taxonomy and phylogeny of the higher categories of cruptodiran turtles based on a cladistic analysis of chromosomal data. Copeia 1983:918-932.

Bickham, J.W. and J.L. Carr. 1983. Taxonomy and phylogeny of the higher categories of cruptodiran turtles based on a cladistic analysis of chromosomal data. Copeia 1983:918-932. Bishop, C.A., R.J. Brooks, J.H. Carey, P. Ng, R.J. Norstrom, and D.R.S. Lean. 1991. The case for a cause-effect linkage between environmental contamination and development in eggs of the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina serpentina) from Ontario, Canada. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health 33(4): 521-548.

Bishop, C.A., R.J. Brooks, J.H. Carey, P. Ng, R.J. Norstrom, and D.R.S. Lean. 1991. The case for a cause-effect linkage between environmental contamination and development in eggs of the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina serpentina) from Ontario, Canada. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health 33(4): 521-548. Bleakney, S. 1957. A snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina serpentina, containing eighty-three eggs. Copeia 1957: 143.

Bleakney, S. 1957. A snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina serpentina, containing eighty-three eggs. Copeia 1957: 143. BLM. 1982b. Moorhead baseline inventory - wildlife. Bureau of Land Management, Miles City District Office. Miles City, MT. 29 pp.

BLM. 1982b. Moorhead baseline inventory - wildlife. Bureau of Land Management, Miles City District Office. Miles City, MT. 29 pp. Bobyn, M.L. and R.J. Brooks. 1994. Interclutch and interpopulation variation in the effects of incubation conditions on sex, survival and growth of hatchling turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Journal of Zoology 233(2): 233-257.

Bobyn, M.L. and R.J. Brooks. 1994. Interclutch and interpopulation variation in the effects of incubation conditions on sex, survival and growth of hatchling turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Journal of Zoology 233(2): 233-257. Boice, R., Q.C. Boice, and R.C. Williams. 1974. Competition and possible dominance in turtles, toads and frogs. Journal of Comparative Physiology and Psychology 86:1116-1131.

Boice, R., Q.C. Boice, and R.C. Williams. 1974. Competition and possible dominance in turtles, toads and frogs. Journal of Comparative Physiology and Psychology 86:1116-1131. Bolek, M.G. 2001. Chelydra serpentina (common snapping turtle) and Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding's turtle) parasites. Herpetological Review 32(1): 37-38.

Bolek, M.G. 2001. Chelydra serpentina (common snapping turtle) and Emydoidea blandingii (Blanding's turtle) parasites. Herpetological Review 32(1): 37-38. Bonin, J., J.L. DesGranges, C.A. Bishop, J. Rogrigue, A. Gendron, J.E. Elliott. 1995. Comparative study of contaminants in the mudpuppy (Amphibia) and the common snapping turtle (Reptilia), St. Lawrence River, Canada. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 28(2): 184-194.

Bonin, J., J.L. DesGranges, C.A. Bishop, J. Rogrigue, A. Gendron, J.E. Elliott. 1995. Comparative study of contaminants in the mudpuppy (Amphibia) and the common snapping turtle (Reptilia), St. Lawrence River, Canada. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 28(2): 184-194. Boulenger, G.A. 1902. On the southern snapping turtle (C. rossignonii). Annals and Magazine of Natural History (7)9(69): 49-51.

Boulenger, G.A. 1902. On the southern snapping turtle (C. rossignonii). Annals and Magazine of Natural History (7)9(69): 49-51. Bramblett, R.G., and A.V. Zale. 2002. Montana Prairie Riparian Native Species Report. Montana Cooperative Fishery Research Unit, Montana State University - Bozeman.

Bramblett, R.G., and A.V. Zale. 2002. Montana Prairie Riparian Native Species Report. Montana Cooperative Fishery Research Unit, Montana State University - Bozeman. Brittle, D. 1991. Chelydra serpentina (snapping turtle). Catesbeiana 11(2): 39.

Brittle, D. 1991. Chelydra serpentina (snapping turtle). Catesbeiana 11(2): 39. Brooks, R.J., D.A. Galbraith, and m.L. Bobyn. 1989. Intraspecific variation in measures of life history in the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. In Proceedings of the First World Congfess of Herpetology. University of Kent, Canterbury, U.K., 11-19 September 1989. The Durrell Institute. Canterbury, Kent, U.K. p. 42.

Brooks, R.J., D.A. Galbraith, and m.L. Bobyn. 1989. Intraspecific variation in measures of life history in the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. In Proceedings of the First World Congfess of Herpetology. University of Kent, Canterbury, U.K., 11-19 September 1989. The Durrell Institute. Canterbury, Kent, U.K. p. 42. Brooks, R.J., G.P. Brown and D.A. Galbraith. 1991. Effects of a sudden increase in natural mortality of adults on a population of the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 69: 1314-1320.

Brooks, R.J., G.P. Brown and D.A. Galbraith. 1991. Effects of a sudden increase in natural mortality of adults on a population of the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 69: 1314-1320. Brooks, R.J., M.L. Bobyn, D.A. Galbraith, J.A. Layfield, and E.G. Nancekivell. 1991. Maternal and environmental influences on growth and survival of embryonic and hatchling snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 69: 2667-2676.

Brooks, R.J., M.L. Bobyn, D.A. Galbraith, J.A. Layfield, and E.G. Nancekivell. 1991. Maternal and environmental influences on growth and survival of embryonic and hatchling snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 69: 2667-2676. Brown, G.P. 1992. Thermal and spatial ecology of a northern population of snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina. M.S. Thesis, University of Guelph. Guelph, Ontario.

Brown, G.P. 1992. Thermal and spatial ecology of a northern population of snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina. M.S. Thesis, University of Guelph. Guelph, Ontario. Brown, G.P. and R.J. Brooks. 1991. Thermal and behavioural responses to feeding in free-ranging turtles, Chelydra serpentina. Journal of Herpetology 25(3): 273-278.

Brown, G.P. and R.J. Brooks. 1991. Thermal and behavioural responses to feeding in free-ranging turtles, Chelydra serpentina. Journal of Herpetology 25(3): 273-278. Brown, G.P. and R.J. Brooks. 1993. Sexual and seasonal differences in activity in northern population of snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina. Herpertologica 49(3): 311-318.

Brown, G.P. and R.J. Brooks. 1993. Sexual and seasonal differences in activity in northern population of snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina. Herpertologica 49(3): 311-318. Brown, G.P., R.J. Brooks, and J.A. Layfield. 1990. Radiotelemetry of body temperatures of free-ranging snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) during summer. Canadian Journal of Zoology 68(8): 1689-1663.

Brown, G.P., R.J. Brooks, and J.A. Layfield. 1990. Radiotelemetry of body temperatures of free-ranging snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) during summer. Canadian Journal of Zoology 68(8): 1689-1663. Brown, G.P., R.J. Brooks, E. Siddall, and S.S. Desser. 1994. Parasites and reproductive output in the snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. Copeia 1994(1): 228-231.

Brown, G.P., R.J. Brooks, E. Siddall, and S.S. Desser. 1994. Parasites and reproductive output in the snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina. Copeia 1994(1): 228-231. Brunson, R.B. 1955. Check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 15: 27-29.

Brunson, R.B. 1955. Check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 15: 27-29. Budhabhatti, J., and E.O. Moll. 1990. Chelydra serpentina (common snapping turtle). Feeding behavior. Herpetological Review 21(1): 19.

Budhabhatti, J., and E.O. Moll. 1990. Chelydra serpentina (common snapping turtle). Feeding behavior. Herpetological Review 21(1): 19. Bureau of Indian Affairs, Department of the Interior. 1981. Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Unpublished report for the Crow/Shell Coal Lease, Crow Indian Reservation, Montana.

Bureau of Indian Affairs, Department of the Interior. 1981. Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Unpublished report for the Crow/Shell Coal Lease, Crow Indian Reservation, Montana. Burke, A.C. 1989. Development of the turtle carapace: implications for the evolution of a novel Bauplan. Journal of Morphology 199(3): .363-378.

Burke, A.C. 1989. Development of the turtle carapace: implications for the evolution of a novel Bauplan. Journal of Morphology 199(3): .363-378. Burke, A.C., and P. Alberch. 1985. The development and homology of the chelonian carpus and tarsus. Journal of Morphology 186(1): 119-131.

Burke, A.C., and P. Alberch. 1985. The development and homology of the chelonian carpus and tarsus. Journal of Morphology 186(1): 119-131. Burke, V.J, R.D. Nagle, M. Ostentoski, and J.D. Congdon. 1993. Common snapping turtles associated with ant mounds. Journal of Herpetology 27: 114-115.

Burke, V.J, R.D. Nagle, M. Ostentoski, and J.D. Congdon. 1993. Common snapping turtles associated with ant mounds. Journal of Herpetology 27: 114-115. Burkholder, G.L. and W.W. Tanner. 1974. Life history and ecology of the Great Basin sagebrush swift, Sceloporus graciosus graciosus Baird and Girard, 1852. BYU Science Bulletin Biological Series 14(5): 1-42.

Burkholder, G.L. and W.W. Tanner. 1974. Life history and ecology of the Great Basin sagebrush swift, Sceloporus graciosus graciosus Baird and Girard, 1852. BYU Science Bulletin Biological Series 14(5): 1-42. Cagle, F.R. 1944a. A Technique for obtaining turtle eggs for study. Copeia 1944: 60.

Cagle, F.R. 1944a. A Technique for obtaining turtle eggs for study. Copeia 1944: 60. Cagle, F.R. 1948. The growth of turtles in Lake Glendale, Illinois. Copeia 1948: 197-203.

Cagle, F.R. 1948. The growth of turtles in Lake Glendale, Illinois. Copeia 1948: 197-203. Carlson, J. (Coordinator, Montana Animal Species of Concern Committee). 2003. Montana Animal Species of Concern January 2003. Helena, MT: Montana Natural Heritage Program and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. In Press. 12p.

Carlson, J. (Coordinator, Montana Animal Species of Concern Committee). 2003. Montana Animal Species of Concern January 2003. Helena, MT: Montana Natural Heritage Program and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. In Press. 12p. Carr, A.F. 1952. Handbook of turltles: the turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

Carr, A.F. 1952. Handbook of turltles: the turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York. Censky, E.J. 1986. Sceloporus graciosus Baird and Girard. Sagebrush lizard. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 386:1-4.

Censky, E.J. 1986. Sceloporus graciosus Baird and Girard. Sagebrush lizard. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 386:1-4. Chiszar, D. and H.M. Smith. 1995. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (common snapping turtle). Herpetological Review 26(4): 208.

Chiszar, D. and H.M. Smith. 1995. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (common snapping turtle). Herpetological Review 26(4): 208. Chiszar, D., R.L. Holland, C. Ristau, and H.M. Smith. 1994. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (common snapping turtle). Herpetological Review 25(4): 162.

Chiszar, D., R.L. Holland, C. Ristau, and H.M. Smith. 1994. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (common snapping turtle). Herpetological Review 25(4): 162. Cink, C.L. 1991. Snake predation on nestling eastern phoebes followed by turtle predation on snake. Kansas Ornithological Society Bulletin 42(3): 29.

Cink, C.L. 1991. Snake predation on nestling eastern phoebes followed by turtle predation on snake. Kansas Ornithological Society Bulletin 42(3): 29. Coaker, M. 1993. The common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) of North America. Southwestern Herpetologists Society Journal 2(3): 33-34.

Coaker, M. 1993. The common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) of North America. Southwestern Herpetologists Society Journal 2(3): 33-34. Collins, J.T. 1991. A new taxonomic arrangement for some North American amphibians and reptiles. Herpetological Review 22:42-43.

Collins, J.T. 1991. A new taxonomic arrangement for some North American amphibians and reptiles. Herpetological Review 22:42-43. Collins, J.T. 1997. Standard common and current scientific names for North American amphibians and reptiles. Fourth edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Herpetological Circular No. 25. 40 pp.

Collins, J.T. 1997. Standard common and current scientific names for North American amphibians and reptiles. Fourth edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Herpetological Circular No. 25. 40 pp. Congdon, J.D. and J.W. Gibbons. 1990. The evolution of turtle life histories. Pages 45-54 in Life history and ecology of the slider turtle. Edited by J.W. Gibbons. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

Congdon, J.D. and J.W. Gibbons. 1990. The evolution of turtle life histories. Pages 45-54 in Life history and ecology of the slider turtle. Edited by J.W. Gibbons. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., U.S.A. Congdon, J.D., S.W. Gotte, S.W., and R.W. Mcdiarmid. 1992. Ontogenetic changes in habitat use by juvenile turtles, Chelydra serpentina and Chrysemys picta. Canadian Field Naturalist 106(2): 241-248.

Congdon, J.D., S.W. Gotte, S.W., and R.W. Mcdiarmid. 1992. Ontogenetic changes in habitat use by juvenile turtles, Chelydra serpentina and Chrysemys picta. Canadian Field Naturalist 106(2): 241-248. Cope, E.D. 1875. Check-list of North American Batrachia and Reptilia; with a systematic list of the higher groups, and an essay on geographical distribution. Based on the specimens contained in the U.S. National Museum. U.S. Natioanl Museum Bulletin 1: 1-104.

Cope, E.D. 1875. Check-list of North American Batrachia and Reptilia; with a systematic list of the higher groups, and an essay on geographical distribution. Based on the specimens contained in the U.S. National Museum. U.S. Natioanl Museum Bulletin 1: 1-104. Costanzo, J.P., J.B. Iverson, M.F. Wright, and R.E. Lee, Jr. 1995. Cold hardiness and overwintering strategies of hatchlings in an assemblage of northern turtles. Ecology 76(6): 1772-1785.

Costanzo, J.P., J.B. Iverson, M.F. Wright, and R.E. Lee, Jr. 1995. Cold hardiness and overwintering strategies of hatchlings in an assemblage of northern turtles. Ecology 76(6): 1772-1785. Coues, E. and H. Yarrow. 1878. Notes on the herpetology of Dakota and Montana. Bulletin of the U.S. Geological Geographic Survey of the Territories 4: 259-291.

Coues, E. and H. Yarrow. 1878. Notes on the herpetology of Dakota and Montana. Bulletin of the U.S. Geological Geographic Survey of the Territories 4: 259-291. Cunnington, D.C. and R.J. Brooks. 1996. Bet-hedging theory and eigenelasticity: a comparison of the life histories of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) and snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 74(2): 291-296.

Cunnington, D.C. and R.J. Brooks. 1996. Bet-hedging theory and eigenelasticity: a comparison of the life histories of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) and snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 74(2): 291-296. Curtis, S. 1994. The big sleep. Montana Outdoors 25(6): 2-7.

Curtis, S. 1994. The big sleep. Montana Outdoors 25(6): 2-7. Daigle, C., A. Desrosiers, and J. Bonin. 1994. Distribution and abundance of common map Turtles, Graptemys geographica, in the Ottawa River, Quebec. Canadian Field Naturalist 108(1): 84-86.

Daigle, C., A. Desrosiers, and J. Bonin. 1994. Distribution and abundance of common map Turtles, Graptemys geographica, in the Ottawa River, Quebec. Canadian Field Naturalist 108(1): 84-86. Darrow, T.D. 1961. Food habits of western painted and snapping turtles in southeastern South Dakota and eastern Nebraska. Unpubl. MS Thesis, University of South Dakota, Vermillion.

Darrow, T.D. 1961. Food habits of western painted and snapping turtles in southeastern South Dakota and eastern Nebraska. Unpubl. MS Thesis, University of South Dakota, Vermillion. Day, D. 1989. Montco Terrestrial Wildlife Monitoring Report. Unpublished report for Montco, Billings, Montana.

Day, D. 1989. Montco Terrestrial Wildlife Monitoring Report. Unpublished report for Montco, Billings, Montana. Day, D., P.J. Farmer, and C.E. Farmer. 1989. Montco terrestrial wildlife monitoring report December, 1987 - July, 1989. Montco, Billings, MT, and Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT.

Day, D., P.J. Farmer, and C.E. Farmer. 1989. Montco terrestrial wildlife monitoring report December, 1987 - July, 1989. Montco, Billings, MT, and Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT. de Santis, B., B. Sheafor, H.M. Smith, and D. Chiszar. 1995. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (common snapping turtle). Herpetological Review 26(3): 154.

de Santis, B., B. Sheafor, H.M. Smith, and D. Chiszar. 1995. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (common snapping turtle). Herpetological Review 26(3): 154. Decker, J.D. 1967. Motility of the turtle embryo, Chelydra serpentina (Linne.). Science 157: 952-954.

Decker, J.D. 1967. Motility of the turtle embryo, Chelydra serpentina (Linne.). Science 157: 952-954. Dinkelacker, S.A., J.P. Costanzo, and R.E. Lee Jr. 2005. Anoxia tolerance and freeze tolerance in hatchling turtles. Journal of Comparative Physiology B Biochemical Systemic and Environmental Physiology 175(3):209-217.

Dinkelacker, S.A., J.P. Costanzo, and R.E. Lee Jr. 2005. Anoxia tolerance and freeze tolerance in hatchling turtles. Journal of Comparative Physiology B Biochemical Systemic and Environmental Physiology 175(3):209-217. Distel, C. 2005. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (Common Snapping Turtle). Flatulence. Herpetological Review 36:310.

Distel, C. 2005. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (Common Snapping Turtle). Flatulence. Herpetological Review 36:310. Dixon, J.R., O.W. Thornton, Jr. 1996. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (common snapping turtle). Herpetological Review 27(1): 31.

Dixon, J.R., O.W. Thornton, Jr. 1996. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (common snapping turtle). Herpetological Review 27(1): 31. Dunham, A.E. and K.L. Overall. 1994. Population responses to environmental change: Life history variation, individual-based models, and the population dynamics of short-lived organisms. American Zoologist 34(3): 382-396.

Dunham, A.E. and K.L. Overall. 1994. Population responses to environmental change: Life history variation, individual-based models, and the population dynamics of short-lived organisms. American Zoologist 34(3): 382-396. Dunson, W.A. 1986. Estuarine populations of the snapping turtle (Chelydra) as a model for the evolution of marine adaptations in reptiles. Copeia 1986:741-756.

Dunson, W.A. 1986. Estuarine populations of the snapping turtle (Chelydra) as a model for the evolution of marine adaptations in reptiles. Copeia 1986:741-756. ECON, Inc. (Ecological Consulting Service), Helena, MT., 1976, Colstrip 10 x 20 Area wildlife and wildlife habitat annual monitoring report, 1976. Proj. 135-85-A. December 31, 1976.

ECON, Inc. (Ecological Consulting Service), Helena, MT., 1976, Colstrip 10 x 20 Area wildlife and wildlife habitat annual monitoring report, 1976. Proj. 135-85-A. December 31, 1976. Ewert, M.A., J.W. Lang, and C.E. Nelson. 2005. Geographic variation in the pattern of temperature-dependent sex determination in the American snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Journal of Zoology (London) 265(1):81-95.

Ewert, M.A., J.W. Lang, and C.E. Nelson. 2005. Geographic variation in the pattern of temperature-dependent sex determination in the American snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Journal of Zoology (London) 265(1):81-95. Ewert, M.E. 1979. The embryo and its egg: development and natural history. In Turtles: perspecgtives and research. Edited by M. Harless and H. Morlock. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York. pp. 333-413.

Ewert, M.E. 1979. The embryo and its egg: development and natural history. In Turtles: perspecgtives and research. Edited by M. Harless and H. Morlock. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York. pp. 333-413. Ewert, M.E. and C.E. Nelson. 1991. Sex determination in turtles: diverse patterns and some possible adaptive values. Copeia 1991: 50-69.

Ewert, M.E. and C.E. Nelson. 1991. Sex determination in turtles: diverse patterns and some possible adaptive values. Copeia 1991: 50-69. Farmer, P. 1980. Terrestrial wildlife monitoring study, Pearl area, Montana June, 1978 - May, 1980. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT.

Farmer, P. 1980. Terrestrial wildlife monitoring study, Pearl area, Montana June, 1978 - May, 1980. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT. Farmer, P. J. 1980. Terrestrial Wildlife Monitoring Study, Pearl Area, Montana, June, 1978 - May, 1980. Tech. Rep. by WESTECH for Shell Oil Co.

Farmer, P. J. 1980. Terrestrial Wildlife Monitoring Study, Pearl Area, Montana, June, 1978 - May, 1980. Tech. Rep. by WESTECH for Shell Oil Co. Feinberg, J.A. and K. Hoffmann. 2004. Chelydra serpentina (Snapping Turtle) and Scaphiopus holbrookii (Eastern Spadefoot). Diet. Herpetological Review 35(4):380.

Feinberg, J.A. and K. Hoffmann. 2004. Chelydra serpentina (Snapping Turtle) and Scaphiopus holbrookii (Eastern Spadefoot). Diet. Herpetological Review 35(4):380. Fergus, C. 1985. Out of their element, turtles bend the regulations. Oceans 18(1): 66-67.

Fergus, C. 1985. Out of their element, turtles bend the regulations. Oceans 18(1): 66-67. Feuer, R.C. 1966. Variation in snapping turtles. Chelydra serpentina Linnaeus: a study in quantitative systematics. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Feuer, R.C. 1966. Variation in snapping turtles. Chelydra serpentina Linnaeus: a study in quantitative systematics. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Utah, Salt Lake City. Feuer, R.C. 1971a. Ecological factors in success and dispersal of the snapping turtle Chelydra serpentina (Linnaeus). Bulletin of the Philadelphia Herpetological Society 19: 3-14.

Feuer, R.C. 1971a. Ecological factors in success and dispersal of the snapping turtle Chelydra serpentina (Linnaeus). Bulletin of the Philadelphia Herpetological Society 19: 3-14. Feuer, R.C. 1971b. Intergradation of the snapping turtles Chelydra serpentina serpentina (Linnaeus, 1758) and Chelydra serpentina osceola Stejneger, 1918. Herpetologica 27(4): 379-384.

Feuer, R.C. 1971b. Intergradation of the snapping turtles Chelydra serpentina serpentina (Linnaeus, 1758) and Chelydra serpentina osceola Stejneger, 1918. Herpetologica 27(4): 379-384. Finkler, M.S. and D.L. Claussen. 1997. Use of the tail in terrestrial locomotor activities of juvenile Chelydra serpentina. Copeia 1997: 884-887.

Finkler, M.S. and D.L. Claussen. 1997. Use of the tail in terrestrial locomotor activities of juvenile Chelydra serpentina. Copeia 1997: 884-887. Finkler, M.S. and D.L. Knickerbocker. 2000. Influence of hydric conditions during incubation and population on overland movement of neonatal snapping turtles. Journal of Herpetology 34(3): 452-455.

Finkler, M.S. and D.L. Knickerbocker. 2000. Influence of hydric conditions during incubation and population on overland movement of neonatal snapping turtles. Journal of Herpetology 34(3): 452-455. Finneran, L.C. 1947. A large clutch of eggs of Chelydra serpentina serpentina (linnaeus). Herpetologica 3: 182.

Finneran, L.C. 1947. A large clutch of eggs of Chelydra serpentina serpentina (linnaeus). Herpetologica 3: 182. Flath, D.L. 1979. Nongame species of special interest or concern: Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes. Wildlife Division, Montana Department of Fish and Game. Helena, MT.

Flath, D.L. 1979. Nongame species of special interest or concern: Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes. Wildlife Division, Montana Department of Fish and Game. Helena, MT. Frair, W. 1972. Taxonomic relations among chelydrid and kinosternid turtles elucidated by serological tests. Copeia 1972:97-108.

Frair, W. 1972. Taxonomic relations among chelydrid and kinosternid turtles elucidated by serological tests. Copeia 1972:97-108. Fraser, G. 1994. Possible predation of a Forster's tern chick by a snapping turtle. Prairie Naturalist 26(1): 33-35.

Fraser, G. 1994. Possible predation of a Forster's tern chick by a snapping turtle. Prairie Naturalist 26(1): 33-35. Frazer, N.B., J.W. Gibbons, and T.J. Owens. 1990. Turtle trapping: preliminary tests of conventional wisdom. Copeia 1990(4): 1150-1152.

Frazer, N.B., J.W. Gibbons, and T.J. Owens. 1990. Turtle trapping: preliminary tests of conventional wisdom. Copeia 1990(4): 1150-1152. Froese, A.D. 1974. Aspects of space use in the common snapping turtle, Chelydra s. serpentina. Unpubl.Ph. D. Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Froese, A.D. 1974. Aspects of space use in the common snapping turtle, Chelydra s. serpentina. Unpubl.Ph. D. Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Froese, A.D. 1978. Habitat preferences of the common snapping turtle, Chelydra s. serpentina (Reptilia, Testudines, Chelydridae). Journal of Herpetology 12: 53-58.

Froese, A.D. 1978. Habitat preferences of the common snapping turtle, Chelydra s. serpentina (Reptilia, Testudines, Chelydridae). Journal of Herpetology 12: 53-58. Froese, A.D. and G.M. Burghardt. 1974. Food competition in captive juvenile snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina. Animal Behavior 22: 735-740.

Froese, A.D. and G.M. Burghardt. 1974. Food competition in captive juvenile snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina. Animal Behavior 22: 735-740. Gaffney, E.S. 1975b. Phylogeny of the chelydrid turtles: a study of shared derived characters of the skull. Fieldiana, Geology 33: 157-178.

Gaffney, E.S. 1975b. Phylogeny of the chelydrid turtles: a study of shared derived characters of the skull. Fieldiana, Geology 33: 157-178. Gaffney, E.S. 1984a. Historical analysis of theories of chelonian relationship. Systematic Zoology 33:283-301.

Gaffney, E.S. 1984a. Historical analysis of theories of chelonian relationship. Systematic Zoology 33:283-301. Gaffney, E.S. 1984b. Progress towards a natural hierarchy of turtles. Studia Geologica Salmanticensia (Studia Palaeocheloniologica I) 1:125-131.

Gaffney, E.S. 1984b. Progress towards a natural hierarchy of turtles. Studia Geologica Salmanticensia (Studia Palaeocheloniologica I) 1:125-131. Galbraith, D.A. 1994. Ecology research on snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) in Ontario, Canada. Asra Journal 1994: 23-49.

Galbraith, D.A. 1994. Ecology research on snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) in Ontario, Canada. Asra Journal 1994: 23-49. Galbraith, D.A. and R.J. Brooks. 1987a. Addition of annual lines in adult snapping turtles Chelydra serpentina. Journal of Herpetology 21: 359-363.

Galbraith, D.A. and R.J. Brooks. 1987a. Addition of annual lines in adult snapping turtles Chelydra serpentina. Journal of Herpetology 21: 359-363. Galbraith, D.A. and R.J. Brooks. 1987c. Survivorship of adult females in a northern population of common snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina. Canadian Journal of Zoology 65(7): 1581-1586.

Galbraith, D.A. and R.J. Brooks. 1987c. Survivorship of adult females in a northern population of common snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina. Canadian Journal of Zoology 65(7): 1581-1586. Galbraith, D.A., B.N. White, R.J. Brooks, and P.T. Boag. 1993. Multiple paternity in clutches of snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) detected using DNA fingerprints. Canadian Journal of Zoology 71(2): 318-324.

Galbraith, D.A., B.N. White, R.J. Brooks, and P.T. Boag. 1993. Multiple paternity in clutches of snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) detected using DNA fingerprints. Canadian Journal of Zoology 71(2): 318-324. Galbraith, D.A., C.A. Bishop, R.J. Brooks, W.L. Simser, and K.P. Lampman. 1988. Factors affecting the density of populations of common snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 66(5): 1233-1240.

Galbraith, D.A., C.A. Bishop, R.J. Brooks, W.L. Simser, and K.P. Lampman. 1988. Factors affecting the density of populations of common snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 66(5): 1233-1240. Galbraith, D.A., C.J. Graesser, and R.J. Brooks. 1988. Egg retention by a snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina, in central Ontario (Canada). Canadian Field Naturalist 102(4): 734.

Galbraith, D.A., C.J. Graesser, and R.J. Brooks. 1988. Egg retention by a snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina, in central Ontario (Canada). Canadian Field Naturalist 102(4): 734. Galbraith, D.A., R.J. Brooks, and M.E. Obbard. 1989. The influence of growth rate on age and body size at maturity in female snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Copeia (4): 896-904.

Galbraith, D.A., R.J. Brooks, and M.E. Obbard. 1989. The influence of growth rate on age and body size at maturity in female snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Copeia (4): 896-904. Garbin, C.P. 1992. Performance of hatchling snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) on single-food diets: a comparison of three commercial foods. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 27(12): 249-251.

Garbin, C.P. 1992. Performance of hatchling snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) on single-food diets: a comparison of three commercial foods. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 27(12): 249-251. Gatten, R.E. 1980. Aerial and aquatic oxygen uptake by freely-diving snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Oecologia 46: 266-271.

Gatten, R.E. 1980. Aerial and aquatic oxygen uptake by freely-diving snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Oecologia 46: 266-271. Gaunt, A.S. and C. Gans. 1969. Mechanics of respiration in the snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina (Linne.). Journal of Morphology 128: 195-228.

Gaunt, A.S. and C. Gans. 1969. Mechanics of respiration in the snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina (Linne.). Journal of Morphology 128: 195-228. Gerholdt, J.E. and B. Oldfield. 1987. Life history notes. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (common snapping turtle). Size. Herpetological Review 18(4): 73.

Gerholdt, J.E. and B. Oldfield. 1987. Life history notes. Chelydra serpentina serpentina (common snapping turtle). Size. Herpetological Review 18(4): 73. Gettinger, R.D., G.L. Paukstis, and G.C. Packard. 1984. Influence of hydric environment on oxygen consumption by embryonic turtles Chelydra serpentina and Trionyx spiniferus. Physiological Zoology 57: 468-473.

Gettinger, R.D., G.L. Paukstis, and G.C. Packard. 1984. Influence of hydric environment on oxygen consumption by embryonic turtles Chelydra serpentina and Trionyx spiniferus. Physiological Zoology 57: 468-473. Gibbons, J.W. 1968b. Growth rates of the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina, in a polluted river. Herpetologica 24: 266-267.

Gibbons, J.W. 1968b. Growth rates of the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina, in a polluted river. Herpetologica 24: 266-267. Gibbons, J.W. and D.H. Nelson. 1978. The evolutionary significance of delayed emergence from the nest by hatchling turtles. Evolution 32: 297-303.

Gibbons, J.W. and D.H. Nelson. 1978. The evolutionary significance of delayed emergence from the nest by hatchling turtles. Evolution 32: 297-303. Gibbons, J.W., S.S. Novak, and C.H. Ernst. 1988. Chelydra serpentina (Linnaeus). Snapping turtle. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 420: 1-4.

Gibbons, J.W., S.S. Novak, and C.H. Ernst. 1988. Chelydra serpentina (Linnaeus). Snapping turtle. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 420: 1-4. Graff, H. and H. Graff. 1991. Snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Newsletter of the Australian Society of Herpetologists Inc. 34(6): 131-133.

Graff, H. and H. Graff. 1991. Snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Newsletter of the Australian Society of Herpetologists Inc. 34(6): 131-133. Graham, T.E. and R.W. Perkins. 1976. Growth of the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina, in a polluted marsh. Maryland Herpetological Society Bulletin 12: 123-125.

Graham, T.E. and R.W. Perkins. 1976. Growth of the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentina, in a polluted marsh. Maryland Herpetological Society Bulletin 12: 123-125. Green, G.A., K.B. Livezey, and R.L. Morgan. 2001. Habitat selection by northern sagebrush lizards (Sceloporus graciosus graciosus) in the Columbia Basin, Oregon. Northwestern Naturalist 82:111-115.

Green, G.A., K.B. Livezey, and R.L. Morgan. 2001. Habitat selection by northern sagebrush lizards (Sceloporus graciosus graciosus) in the Columbia Basin, Oregon. Northwestern Naturalist 82:111-115. Gutzke, W.H.N. 1984. Modification of the hydric environment by eggs of snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 62(12): 2401-2403.

Gutzke, W.H.N. 1984. Modification of the hydric environment by eggs of snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 62(12): 2401-2403. Gutzke, W.H.N. and D. Crews. 1988. Embyonic temperature determines adult sexuality in a reptile. Nature 332: 832-834.

Gutzke, W.H.N. and D. Crews. 1988. Embyonic temperature determines adult sexuality in a reptile. Nature 332: 832-834. Haas, A. 1985. Year-long outdoor behavior of the snapping turtle Chelydra serpentina serpentina in southern Germany (Testudines, Chelydridae). Salamandra 21(1): 1-9.

Haas, A. 1985. Year-long outdoor behavior of the snapping turtle Chelydra serpentina serpentina in southern Germany (Testudines, Chelydridae). Salamandra 21(1): 1-9. Hamilton, A.M. and A.H. Freedman. 2002. Effects of deer feeders, habitat and sensory cues on predation rates on artificial turtle nests. American Midland Naturalist 147:123-134.

Hamilton, A.M. and A.H. Freedman. 2002. Effects of deer feeders, habitat and sensory cues on predation rates on artificial turtle nests. American Midland Naturalist 147:123-134. Hamilton, W.J., Jr. 1940. Observations on the reproductive behavior of the snapping turtle. Copeia 1940: 124-126.

Hamilton, W.J., Jr. 1940. Observations on the reproductive behavior of the snapping turtle. Copeia 1940: 124-126. Hammer, D.A. 1971a. Reproductive behavior of the common snapping turtle. Canadian Herpetological Society 1: 9-13.

Hammer, D.A. 1971a. Reproductive behavior of the common snapping turtle. Canadian Herpetological Society 1: 9-13. Hammer, D.A. 1971b. The durable snapping turtle. Natural History 80: 59-65.

Hammer, D.A. 1971b. The durable snapping turtle. Natural History 80: 59-65. Hanson, J. No Date. Unpublished report on Youngs Creek. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Hardin, MT. 14 p.

Hanson, J. No Date. Unpublished report on Youngs Creek. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Hardin, MT. 14 p. Hebert, C.E., V. Glooshenko, G.D. Haffner, and R. Lazar. 1993. Organic contaminants in snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) populations from southern Ontario, Canada. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 24(1): 35-43.

Hebert, C.E., V. Glooshenko, G.D. Haffner, and R. Lazar. 1993. Organic contaminants in snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) populations from southern Ontario, Canada. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 24(1): 35-43. Hemphill, N. and W. Worthey. 1994. Do predaceous turtles affect stream fishes? International Vereinigung Fuer Theoretische Und Angewandte Limnologie Verhandlungen 25(4): 2105-2107.

Hemphill, N. and W. Worthey. 1994. Do predaceous turtles affect stream fishes? International Vereinigung Fuer Theoretische Und Angewandte Limnologie Verhandlungen 25(4): 2105-2107. Hendricks, P. 1999a. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Bureau of Land Management Miles City District, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 80 p.

Hendricks, P. 1999a. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Bureau of Land Management Miles City District, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 80 p. Hendricks, P. and L.N. Hendricks. 2002. Predatory attack by green-tailed towhee on sagebrush lizard. Northwestern Naturalist 83:57-59.

Hendricks, P. and L.N. Hendricks. 2002. Predatory attack by green-tailed towhee on sagebrush lizard. Northwestern Naturalist 83:57-59. Hogg, D.M. 1975. The snapping turtles of Wye Marsh. Ontario Fish and Wildlife Review 14: 16-20.

Hogg, D.M. 1975. The snapping turtles of Wye Marsh. Ontario Fish and Wildlife Review 14: 16-20. Holman, A.J. 1988. The status of Michigan's Pleistocene herpetofauna. Michigan Academician 20(2): 125-132.

Holman, A.J. 1988. The status of Michigan's Pleistocene herpetofauna. Michigan Academician 20(2): 125-132. Holman, J.A. and J.N. Mcdonald. 1986. A late quaternary herpetofauna from Saltville, Virginia (USA). Brimleyana 0(12): 85-100.

Holman, J.A. and J.N. Mcdonald. 1986. A late quaternary herpetofauna from Saltville, Virginia (USA). Brimleyana 0(12): 85-100. Hotaling, E.C., D.C. Wilhoft, and S.B. McDowell. 1985. Egg position and weight of hatchling snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina, in natural nests. Journal of Herpetology 19(4): 534-536.

Hotaling, E.C., D.C. Wilhoft, and S.B. McDowell. 1985. Egg position and weight of hatchling snapping turtles, Chelydra serpentina, in natural nests. Journal of Herpetology 19(4): 534-536. Hoyt, J.S.Y. 1941. The incubation period of the snapping turtle. Copeia 1941: 180.

Hoyt, J.S.Y. 1941. The incubation period of the snapping turtle. Copeia 1941: 180. Humphrey, R., D. Chiszar, and H.M. Smith. 1995. Chelydra serpentina (snapping turtle). Herpetological Review 26(2): 106.

Humphrey, R., D. Chiszar, and H.M. Smith. 1995. Chelydra serpentina (snapping turtle). Herpetological Review 26(2): 106. Iverson, J.B. 1992a. A revised checklist with distribution maps of the turtles of the world. Paust Printing, Richmond, Indiana.

Iverson, J.B. 1992a. A revised checklist with distribution maps of the turtles of the world. Paust Printing, Richmond, Indiana. Iverson, J.B., H. Higgins, A. Sirulnik, and C. Griffiths. 1997. Local and geographic variation in the reproductive biology of the snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Herpetologica 53(1): 96-117.

Iverson, J.B., H. Higgins, A. Sirulnik, and C. Griffiths. 1997. Local and geographic variation in the reproductive biology of the snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Herpetologica 53(1): 96-117. Janzen, F.J. 1990. Egg size and hatching success of snapping turtle eggs: evaluation of natural selection. American Zoologist 30: 55A.

Janzen, F.J. 1990. Egg size and hatching success of snapping turtle eggs: evaluation of natural selection. American Zoologist 30: 55A. Janzen, F.J. 1992. Heritable variation for sex ratio under environmental sex determination in the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Genetics 131(1): 155-161.

Janzen, F.J. 1992. Heritable variation for sex ratio under environmental sex determination in the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Genetics 131(1): 155-161. Janzen, F.J. 1993. An experimental analysis of natural selection on body size of hatchling turtles. Ecology 74(2): 332-341.

Janzen, F.J. 1993. An experimental analysis of natural selection on body size of hatchling turtles. Ecology 74(2): 332-341. Janzen, F.J. 1994b. Temperature-dependent sex determination influences the mortality of hatchling snapping turtles in nature. American Zoologist 34(5): 9A.