View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Western Water Shrew - Sorex navigator

Native Species

Global Rank:

G5

State Rank:

S4

(see State Rank Reason below)

Agency Status

USFWS:

USFS:

BLM:

External Links

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is common to uncommon across forested areas of western and central Montana. No threats are identified.

General Description

A large, semiaquatic, blackish-gray shrew with a long bicolored tail and large hind feet fringed with short stiff hairs. Total length is 14 to 16 cm (5.5 to 6.3 inches) including a 6 to 8 cm (2.4 to 3.1 inch) tail. The dense fur is glossy blackish gray above and paler or silvery beneath. Middle toes of hind feet (18 to 20 mm) are partially webbed. For good descriptions and illustrations see Burt and Grossenheider (1976), Godin (1977), Hall (1981), Beneski and Stinson (1987), Clark and Stromberg (1987), and Merritt and Matinko (1987). The sexes are similar in size and color. Sexually active males (February to September) have prominent dermal glands on each side between fore and hind legs. They show in S. p. navigator as an 8-mm oval patch of white hair (Conaway 1952). Immatures are similar in color to adults. The skull is large and heavy for a shrew, generally more than 19.5 mm long in S. p. punctulatus. The first two unicuspid teeth are noticeably larger than the next two (Banfield 1974), the third unicuspid is smaller than the fourth (Godin 1977), and the fifth is greatly reduced (Pagels 1986). For comparative illustrations of shrew dentition, see Conaway (1952), Banfield (1974), Churchfield (1990). The teeth of North American shrews show some reddish brown pigmentation. Scats of Western Water Shrews are quite distinctive, black and granular in structure, being full of remains of invertebrate exoskeletons. They are often deposited in middens on the banks of streams, in surface burrows, at burrow entrances, in the lee of rocks at the stream edge, or even sometimes quite prominently on the tops of stones (Churchfield 1990). Western Water Shrew hairs are roughly H-shape in cross section, with inner surfaces deeply ridged (see illustration in Churchfield 1990).

Western Water Shrew was previously known as the Northern Water Shrew (S. palustris), but recent analysis of genetic differences across this species range provided evidence that the species should be split into three species with the Western Water Shrew occuring in Montana.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Stiff hairs along the sides of the hind feet are found only in the Western Water Shrew and the Pacific Water Shrew (Sorex bendirii). The latter, a Pacific Northwest species, differs in being slightly larger (8.9 to 9.7 cm, 3.5 to 3.8 inches, body length) and dark brown rather than blackish-gray (Burt and Grossenheider 1976). See Carraway (1995) for a key to western North American soricids based primarily on dentaries.

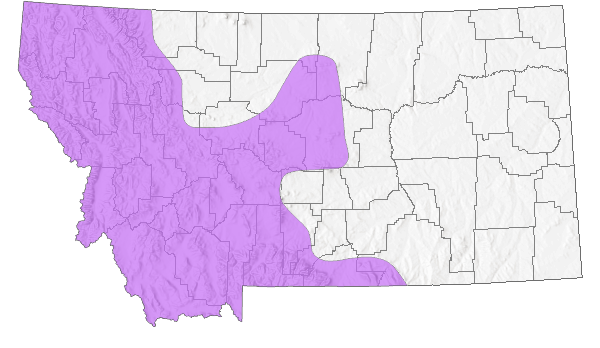

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

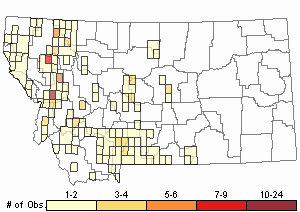

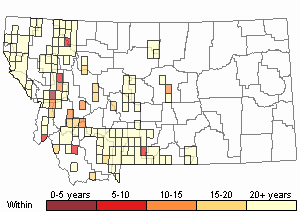

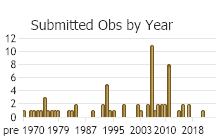

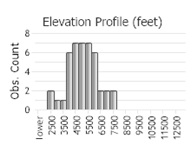

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 197

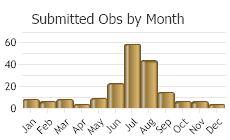

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

Non-migratory.

Habitat

In streamside habitat in coniferous forests, particularly in or under overhanging banks or crevices; prefer good cover (Conaway 1952). However, also found in seasonal streams and small seeps (Kinsella 1967). Also above timberline (Hoffmann and Pattie 1968).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Alpine

Alpine - Vegetated

Forest and Woodland

Deciduous Forest and Woodland

Low Elevation - Xeric Forest and Woodland

Montane - Subalpine Forest and Woodland

Shrubland

Foothills - Montane Shrubland

Sagebrush Shrubland

Grassland

Lowland - Prairie Grassland

Montane - Subalpine Grassland

Wetland and Riparian

Alpine Riparian and Wetland

Peatland

Riparian and Wetland Forest

Riparian Shrubland

Wet Meadow and Marsh

Recently Disturbed or Modified

Harvested Forest

Insect-Killed Forest

Introduced Vegetation

Human Land Use

Agriculture

Developed

Food Habits

Aquatic insect larvae, also some vegetable matter, Oligochaetes, other shrews, arachnids, and small fish (Conaway 1952). Captures in small seeps (Kinsella 1967) imply dietary flexibility.

Ecology

A captive specimen required cold water. Used smell and tactile senses to capture fish. Fur would become soaked within several minutes immersion, and specimen dried itself by working fur with hind feet (Conaway 1952).

Reproductive Characteristics

Males produce sperm December to August. Pregnant or lactating females found February to August. Several litters/season, around 6 young/litter. Males reproductively mature 2nd year, females 1st year but often do not produce litter until 2nd year.

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Banfield, A.W.F. 1974. The mammals of Canada. University of Toronto Press for National Museum of Natural Science and the National Museums of Canada, 438 pp.

Banfield, A.W.F. 1974. The mammals of Canada. University of Toronto Press for National Museum of Natural Science and the National Museums of Canada, 438 pp. Beneski, J.T. and D.W. Stinson. 1987. Sorex palustris. American Society of Mammalogists, Lawrence, KS. Mammalian Species No. 296:1-6.

Beneski, J.T. and D.W. Stinson. 1987. Sorex palustris. American Society of Mammalogists, Lawrence, KS. Mammalian Species No. 296:1-6. Burt, W.H. and R.P. Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to the mammals. Third edition. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 289 pp.

Burt, W.H. and R.P. Grossenheider. 1976. A field guide to the mammals. Third edition. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. 289 pp. Carraway, L.N. 1995. A key to recent Soricidae of the western United States and Canada based primarily on dentaries. Occasional Papers of the Natural History Museum, University of Kansas (175):1-49.

Carraway, L.N. 1995. A key to recent Soricidae of the western United States and Canada based primarily on dentaries. Occasional Papers of the Natural History Museum, University of Kansas (175):1-49. Churchfield, S. 1990. The natural history of shrews. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. 178 pp.

Churchfield, S. 1990. The natural history of shrews. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. 178 pp. Clark, S.G. and M.R. Stromberg. 1987. Mammals in Wyoming. University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, Public Education Series Number 10. xii + 314 pp.

Clark, S.G. and M.R. Stromberg. 1987. Mammals in Wyoming. University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, Public Education Series Number 10. xii + 314 pp. Conaway, C.H. 1952. Life history of the water shrew (Sorex palustris navigator). American Midland Naturalist 48:219-248.

Conaway, C.H. 1952. Life history of the water shrew (Sorex palustris navigator). American Midland Naturalist 48:219-248. Godin, A.J. 1977. Wild mammals of New England. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 304 pp.

Godin, A.J. 1977. Wild mammals of New England. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 304 pp. Hall, E.R. 1981. The mammals of North America, volumes I and II. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. 1181 pp.

Hall, E.R. 1981. The mammals of North America, volumes I and II. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. 1181 pp. Hoffmann, R.S. and D.L. Pattie. 1968. A guide to Montana mammals: identification, habitat, distribution, and abundance. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 133 p.

Hoffmann, R.S. and D.L. Pattie. 1968. A guide to Montana mammals: identification, habitat, distribution, and abundance. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 133 p. Kinsella, J.M. 1967. Unusual habitat of the water shrew in western Montana. J. Mammal. 48(3):475-477.

Kinsella, J.M. 1967. Unusual habitat of the water shrew in western Montana. J. Mammal. 48(3):475-477. Merritt, J.F. and R.A. Matinko. 1987. Guide to the mammals of Pennsylvania. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA.

Merritt, J.F. and R.A. Matinko. 1987. Guide to the mammals of Pennsylvania. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA. Pagels, J.F. 1986. Key to the Soricidae of Virginia. Unpublished.

Pagels, J.F. 1986. Key to the Soricidae of Virginia. Unpublished.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing?

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Western Water Shrew"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Mammals"