View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Ventenata - Ventenata dubia

Other Names:

North African Grass, Wiregrass, North Africa Grass

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Ventenata dubia is grass that is native to central and southern Europe and north Africa to Iran, and was introduced into North America (Crins in Flora of North America (FNA)). A conservation status rank is not applicable (SNA) because Ventenata dubia is a non-native vascular plant in Montana that is not a suitable target for conservation activities.

Ventenata dubia is a State of Montana noxious weed.

General Description

PLANTS: Cool season, winter annual bunchgrass - tufted from a few stems, 15-50 (70) cm tall. Sources: Lesica et al. 2022; Crins in FNA 2007; Harvey and Mangold 2018

LEAVES: Stems have 3-4 exposed, purplish-black leaf nodes and are puberulent below the node. Blades 1–3 mm broad, inrolled, and ascending. Sheaths have overlapping margins. Ligule membranous, 1-8 mm long. Sources: Lesica et al. 2022; Crins in FNA 2007

INFLORESCENCE: Open panicle, 20-40 cm long, with 1-5 spikelets borne at the very distal ends of branches. Lower branch nodes have 2-5 branches. Spikelets 6-10 mm long with mostly 3 florets; lowest florets often staminate and remainder are bisexual. Callus well-developed, bearded (hairy). Glumes unequal, distinctly ribbed or veined, and enveloping the florets. Lower glume 4.5-6 mm long. Upper glume 6-8 mm long. Lemmas dimorphic, 5-7.5 mm long. Within a spikelet, the lowest lemma has straight awns, up to 4 mm long while the upper two lemmas have a tip with bifid teeth, a twisted and bent (geniculate) awn of 10-16 mm long, and are fertile. Paleas well-developed, 4-5 mm long. Anthers 1-2 mm long. Sources: Lesica et al. 2022; Crins in FNA 2007

TAXONOMY & NOMENCLATURE

In the United States, Ventenata was documented in Washington in 1952, reported by Baker in a 1964 publication, and subsequently illustrated and added by Hitchcock et al. into the 1969 Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest.

The genus Ventenata was named for Pierre Etienne Ventenat (1757-1805), a professor of botany in Paris, France.

The name “wiregrass” is in reference to the hardened stems that can become tangled around a swather of a mowing machine (Prather 2015).

Phenology

Predominantly germinates in the fall (Harvey and Mangold 2018). Inflorescence emerges in late May through June (Harvey and Mangold 2018). Flowering may continue through August (CABI 2015).

Diagnostic Characteristics

The identification of

Ventenata dubia can be deceptive in the field because

after maturity the lowest floret with its straight awn remains on the plant while the upper floret with its bent awn disarticulates. Thus, the grass can resemble a 1-flowered member of the Stipeae and Eragrosteae tribes who have terminally-awned lemmas and relatively short glumes (Chambers 1985). The deception increases when the lowest floret also produces a seed (caryopsis), as occasionally can happen (Chambers 1985).

Ventenata –

Ventenata dubia, non-native, undesirable, Noxious

* Growth Form: Winter annual bunchgrass. Mature plants green to tawny brown.

* Leaves (mature): Narrow, folded lengthwise (inrolled), glabrous to puberulent,

and ascending. At the seedling stage, leaves are narrow and more needle-like when compared to Cheatgrass and Japanese Brome.

* Ligule: Long, membranous, 1-8 mm, and matched above by a purple-black node.

* Inflorescence & Stem: Open, airy, pyramidal-shaped, upright panicle that emerges (May-June) while stems harden.

* Callus: Bearded (hairy)

* Glumes: 7-nerved

and smooth.

* Lemmas: Dimorphic. Lowest lemma with straight, persistent awn. Upper lemmas with a bifid tip and a twisted, bent awn (June-July), 1-1.6 cm long that disarticulates with the floret.

* Caryopsis: Seeds (from upper florets) retain bent, twisted awn after dispersal.

Wild Oats –

Avena fatua, non-native

* Growth Form: Annual bunchgrass.

* Leaves: 5-10 mm wide, flat and lax.

* Ligule: Membranous.

* Inflorescence: Open panicle.

* Lemmas: Single acute tip, hairless to often hairy, and with a twisted, bent blackish awn, 3-4 cm long.

* Callus: Conspicuously hairy.

* Caryopsis: Seeds (from upper florets) retain bent, twisted awn after dispersal

Cheatgrass –

Bromus tectorum, exotic, undesirable, and State-Regulated

* Growth Form: Annual bunchgrass. Mature plants turn reddish-purple.

* Leaves: 2-4 mm wide and softly hairy on both sides. At seedling stage leaves are hairier and twisted when compared to Ventenata.

* Inflorescence: Open, often nodding panicle.

* Lemmas: Hairy. Awns are straight, twisted, reddish-purple at maturity, 12-20 cm long, and stick to clothing and fur.

* Glumes: 1st Glume is 1-veined.

Japanese Brome –

Bromus japonica, non-native, undesirable

* Growth Form: Annual bunchgrass.

* Leaves: 2-4 mm wide. At seedling stage leaves are hairier and twisted when compared to Ventenata.

* Inflorescence: Open panicle with branches drooping to one side.

* Lemmas: Broad. Awns are straight to curved downward, 2-6 mm long, at maturity.

* Glumes: Usually hairy. 1st Glume is 3-to 5-veined.

Annual Hairgrass –

Deschampsia danthonioides, native, desirable

* Growth Form: Annual bunchgrass that grows in disturbed, dry forested understories.

* Leaves: 1-1.5 mm wide, and wither by anthesis.

* Ligules: Membranous, 2-3 mm long

without a purplish-black node.

* Inflorescence: Contracted to open panicle.

* Spikelets: Mostly 2 florets, fertile.

* Lemma: With a bent awn 1.5-3 mm long and arising from middle of its back.

Identifying Ventenata & Annual Grasses:

*

Identifying Invasive Annual Grasses in Montana - video.

*

Identifying Ventana early in the season - video

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Non-native

Non-native

Range Comments

Plants are native to central and southern Europe and north Africa to Iran (Crins in FNA 2007). Ventenata was introduced into the United States from Eurasia and Africa (Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018). The first North American collection was documented in Washington in 1952 (Crins in FNA 2007). Ventenata grows in sporadic or ephemeral occurrences from southern British Columbia south to California and eastward to Alberta, Montana, Wyoming, and Utah; plants also occur eastward in Canada to Ontario and Quebec and are found in the Great Lakes region (Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018; Prather 2015). Plants have established in some crop and pasture lands of eastern Washington and western Idaho (Old and Callihan 1986). As evidenced by herbarium specimens, the species is showing its ability to invade into low elevation sagebrush habitats (Jones et al. 2018).

The earliest Ventenata collection in Montana was made in 1995 in Ravalli County by W.E. Albert (MONT 79339;CPNWH 2025). At that time Albert found it locally common, documented it at several other roadside localities, and surmised it was introduced by motor vehicles.

Links to maps and other distributional information on non-native species:

Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Habitat Tool (INHABIT) from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Compendium from the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI)

EDDMapS Species Information EDDMapS Species Information

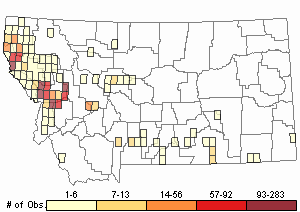

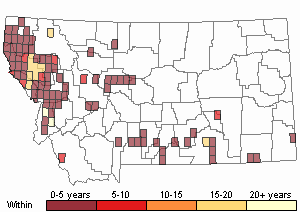

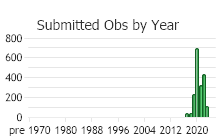

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 2572

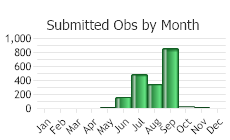

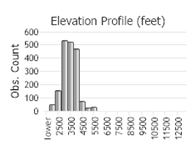

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Ventenata is adapted to characteristic Mediterranean climates with cool, wet winters and hot, dry summers (Harvey and Mangold 2018). In the Inland Northwest, field observations have found that plants grow in areas receiving moderate annual precipitation from 14 to 44 inches and at elevations ranging from 33 to 5,900 feet.

In Montana sporadic or ephemeral populations grow along roadsides and in pastures and rangeland that exhibits a significant disturbance history (Lesica et al. 2022). Ventenata can also invade winter grain fields, hayfields, Conservation Reserve Program lands, and sagebrush steppe habitats (Harvey and Mangold 2018).

Ecology

ECOLOGICAL TOLERANCE

Ventenata tends to occur in moist areas from higher precipitation and/or where topography retains greater soil moisture (Jones et al. 2018). Microsites that collect more moisture within a drier habitat type may harbor plants that become a source population for future dispersal.

SAGEBRUSH STEPPE COMMUNITIES

Historic land-use, drought and climatic changes, altered fire regimes, and biological invasions are interacted to create major system state changes in sagebrush steppe communities (Nicolli et al. 2020). Ventenata was documented to rapidly spread in low-elevation sagebrush steppe habitat at the John Day Fossil Beds national Monument in Oregon (Nicolli et al. 2020). Ventenata was initially identified at the monument in 2014, prior to establishing a formal monitoring study. Within the monitored area of 4,674 hectares (ha), Ventenata was not found on the monitoring plots in 2015, was found on 21 ha in 2016, peaked in occurrence to 138 ha in 2018, and decreased to 63 ha in 2019. Monitoring also showed that within invaded areas, populations became denser from 2015 to 2019. During this time interval, the driest winter was experienced in 2016, when plants were initially found in the monitoring plots, and the wettest winter was experienced in 2018, prior to the Ventenata population increase. Ventenata was found in plots that exemplified a spectrum of environmental conditions. Ventenata plants correlated with deep, well-drained clay and clay-loam soils. Where Ventenata plants were found, all but one plot also had Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), an ubiquitous species on the monument, and just under half the plots also had Medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusae). Over the four-year study, Ventenata increased by 300% at the monument. In corroboration with other research, the authors concluded that Ventenata invasion poses an existential threat to the ecological integrity of the sagebrush steppe, especially areas with land management protections (Jones et al. 2018).

PLANT SPECIES INTERACTIONS & ASSOCIATIONS

Ventenata, Cheatgrass, and Medusahead are non-native, annual grasses that share similar life-history traits (Jones et al. 2018). In southwestern Idaho and one county in eastern Oregon the following interactions were observed:

* As plant species diversity (richness) decreases, invasive species presence increases.

* As plant species diversity (richness) decreases, Ventenata cover increases.

* Ventenata is less prevalent in dry, intact shrub communities.

* Exotic Indicator Plant Species that positively (stable; increase) associate with Ventenata in this study and occur in Montana include Rush Skeletonweed (Chondrilla juncea; noxious), Needle-leaf Navarretia (Navarretia intertexa), and Mudusahead.

* Native Indicator Plant Species that positively (stable; increase) associate with Ventenata in this study include the annual forbs that occupy disturbed, moist sites: Panicled Willowherb (Epilobium brachycarpum), Foxtail Barley (Hordeum jubatum), and American Bird’s-foot Trefoil (Lotus unifoliolatus).

* Native Indicator Plant Species that negatively associate with Ventenata in this study and occur in Montana include: Yarrow (Achillea millifolium), Big Sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), Three-tip Sagebrush (Artemisia tripartita), Snowbrush Ceanothus (Ceanothus velutinus), and Bitterbrush (Purshia tridentata)

* Exotic Indicator Plant Species that negatively associate with Ventenata in this study and occur in Montana include: Cheatgrass, Prickly Lettuce (Lactuca serriola), and Foxtail Fescue (Vulpia myuros).

Ventenata is capable of displacing Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) and Medusahead

(Prather and Burke 2011).

Reproductive Characteristics

Plants reproduce by seed.

FLORET

Typically there are three florets: lowest floret is usually staminate and two upper florets are fertile.

FRUIT & GENETICS

The fruit is a caryopsis. Caryopsis, about 3 mm long, is diploid with a chromosome number of 2n=14 (Crins in FNA 2007).

LIFE CYCLE

Ventenata is a winter annual that predominantly germinates in fall (Harvey and Mangold 2018). Germination has been documented at 8 degrees Celsius with about 0.75 inches of precipitation in soils with a silt loam texture (Prather 2015). Late winter or spring germination can sometimes occur, less than 15% of germinated seeds (Harvey and Mangold 2018; Prather 2015). The spikelet disarticulates above and below the glumes making the floret the unit of dispersal (Lesica et al. 2022). The geniculate awns of the upper lemmas easily detach to cling to fur, clothing, and machinery (Harvey and Mangold 2018). Each plant produces from 15 to 35 seeds and dense stands have been calculated to produce 2,800 to 3,700 seeds per square foot (Harvey and Mangold 2018).

Ventenata was found to have a greater seedling survivorship of 100% when germinated under complete litter cover (Wallace et al. 2015). This demonstrated that in thatch-maintained microsites, the higher moisture levels positively promoted germination. In a greenhouse experiment, total cumulative soil moisture was apparently more important to germination then the timing and intensity of precipitation events (Bansal et al. 2014).

It is suggested that early phases of invasion by Ventenata is characterized by a patchy distribution, and that decades of presence can develop into monocultures (Jones et al. 2018).

Economic Value

In the Inland Northwest, Ventenata has caused significant ecological and economical harm to perennial grass habitats (Harvey and Mangold 2018). In northern Idaho and eastern Washington, losses for pasture and grass-hay are estimated at over $20 million annually (Prather 2015).

Management

STATE DESIGNATION(S)The Montana Department of Agriculture listed Ventenata in 2019 as a Priority 2A noxious weed. It was listed because of documented infestations and continual spread into native rangeland, pastures, and roadsides. Priority 2A noxious weeds require eradication or containment and management is prioritized by local weed districts (https://agr.mt.gov/Noxious-Weeds).

INTEGRATED VEGETATION MANAGEMENTAn integrated vegetative management approach provides the best long-term control, and requires that land-use objectives and a desired plant community be identified (Shelly et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Once identified, an integrated weed management strategy that promotes a weed-resistant plant community and serves other land-use objectives such as livestock forage, wildlife habitat, or recreation can be developed.

The U.S. Geological Survey published an annotated bibliography of scientific research on Ventenata from 2010 to 2020 Poor et al. 2021).

DISPERSALVentenata can be introduced as a seed contaminant in Kentucky bluegrass, hay, and annual crops (Prather 2015). This is especially a problem in the USA where it is not subject to seed laws. Plants usually spread along roadways and trails. In Powder River area of Big Horn County, Ventenata may have been brought in on equipment used to control fires. Vehicles can pick up seeds, and florets easily cling to clothing and fur.

PREVENTION [Adapted from Piper in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Preventing the establishment of Ventenata can be accomplished by many practices:

* Learn how to accurately identify Ventenata in order to detect occurrences early and minimize invasions.

* Prevent vehicles from driving through, and animals from grazing within, infested areas.

* Thoroughly wash the undercarriage of vehicles and wheels in a designated area before moving to an un-infested area.

* Frequently monitor for new plants, and when found implement effective control methods.

* Maintain proper grazing management that creates resilience to noxious weed invasion.

* Locate areas where the risk for invasion is higher by studying the existing flora and site characteristics, such as moist microsites and disturbed land (Jones et al. 2018). In sagebrush steppe habitats:

1) Use Medusahead as an indicator species to locate potential areas of future Vententa invasion, and

2) Search out moist microsites to conduct early detection and if present implement control in these places where this grass becomes more competitive.

PHYSICAL and CULTURAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Harvey and Mangold 2018]

Mowing has shown to have limited control for small infestations. Before plants develop seeds, mowing needs to occur multiple times until the soil is dry and Ventenata can no longer grow (Prather 2015). The wiry stems and bent-awns make the plant difficult to cut. After mowing, plants have the potential to produce a second flush of florets and seeds. Thatch can create a microsite that promotes Ventenata germination. See also Reproductive Characteristics – Life Cycle.

CHEMICAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Harvey and Mangold 2018]

Harvey and Mangold (2018) summarized chemical control for Ventenata. Ventenata has shown resistence against glyphosphate and sethoxydim though imazapic is presumably effective (CABI 2015). As of 2018, Esplanade 200 SC [active ingredient (ai) indaziglam], Axiom DF [ai flufenacet and metribuzin], and sinbar WDG [ai terbacil] were labelled to control Ventenata with limited application rights of way and natural areas. Outrider [ai sulfosulfuron], Plateau/Panoramic [ai imazapic ammonium salt], and Laramie 25 DF [ai rimsulfuron] which are labelled for use on Cheatgrass (

Bromus tectorum) and Japanese Brome (

Bromus japonicus) have also been effective on Ventenata.

The active ingredient of indaziflam was previously marketed under the trade mark name of Esplanade which is restricted to industrial vegetation management. Indaziflam, under the trade mark name of Rejuvra has been approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for use on rangeland, CRP, and natural areas including sites grazed by livestock. Rejuvra has successfully controlled annual grasses including Ventenata, Cheatgrass, Japanese Brome, and Medusahead. The chemical should be applied prior to seed germination; it interferes with cellulose biosynthesis to reduce emergence. For further research information, search the

Montana State University Extension and

University of Wyoming Weed Program websites.

GRAZING CONTROLS [Adapted from Harvey and Mangold 2018]

Ventenata is considered unpalatable for domesticated livestock and native ungulates, such as deer, elk, pronghorn, and bighorn sheep. Grazing animals in places with Ventenata populations does not provide an effective control because this grass has a high silica content and its thin, wiry stature adds to its unpalatability.

For assistance with Ventenata identification and population control, contact the Montana Department of Agriculture, County Extension Agent or Weed Coordinator, or

Montana State University Schutter Diagnostic LabUseful Links:Central and Eastern Montana Invasive Species TeamMontana Invasive Species websiteMontana Biological Weed Control Coordination ProjectMontana Department of Agriculture - Noxious WeedsMontana Weed Control AssociationMontana Weed Control Association Contacts WebpageMontana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks - Noxious WeedsMontana State University Integrated Pest Management ExtensionWeed Publications at Montana State University Extension - MontGuides

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Ventenata poses a threat to pasturelands, livestock grazing, recreation, many native habitats, and numerous native plant and animal species (CABI 2015; Harvey and Mangold (2018); Jones et al. 2018; Nicolli et al. 2020).

Ventenata has become increasingly invasive in grasslands and pasturelands of the Inland Northwest, and is expanding into low elevation sagebrush steppe habitat (Jones et al. 2018). Ventenata itself has poor forage value. In Washington, Ventenata has caused substantial ecological and economic impacts in perennial- and annual-dominated grasslands (Jones et al. 2018). In north-central Idaho, researchers have documented the displacement of perennial grasses and a significant decline in forage production within small pasture, grass-hay, and grass systems caused by an invasion of Ventenata (Prather and Burke 2011). In northern Idaho, an invasion of Ventenata has shown a decline in nesting success of insectivorous birds because of a loss in biodiversity on lands managed for conservation (Mackey 2014). It is suggested that early phases of invasion by Ventenata is characterized by a patchy distribution, and that decades of presence can develop into monocultures (Jones et al. 2018).

Ventenata invasion poses an existential threat to the ecological integrity of the sagebrush steppe, especially areas with land management protections (Jones et al. 2018; Nicolli et al. 2020). Ventenata has invaded low elevation sagebrush steppe habitats, which creates the potential to reduce forage production for wildlife and livestock species and impacting recreation.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Chambers, Kenton L. 1985. Pitfalls in Identifying Ventenata dubia (Poaceae). Madrono. April. Volume 32, Number 2, pp. 120-121

Chambers, Kenton L. 1985. Pitfalls in Identifying Ventenata dubia (Poaceae). Madrono. April. Volume 32, Number 2, pp. 120-121 Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 2007. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Volume 24. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae, Part 1. Oxford University Press, Inc., NY. xxxiii + 911 pp.

Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 2007. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Volume 24. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae, Part 1. Oxford University Press, Inc., NY. xxxiii + 911 pp. Harvey, Audrey, and Jane Mangold. 2018. Ventenata. MontGuide, Montana State University Extension, Bozeman, Montana.

Harvey, Audrey, and Jane Mangold. 2018. Ventenata. MontGuide, Montana State University Extension, Bozeman, Montana. Hitchcock, C. L., A. Cronquist, M. Ownbey, and J. W. Thompson. 1969. Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest. Part I: Vascular Cryptogams, Gymnosperms and Monocotyledons. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 914 pp.

Hitchcock, C. L., A. Cronquist, M. Ownbey, and J. W. Thompson. 1969. Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest. Part I: Vascular Cryptogams, Gymnosperms and Monocotyledons. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 914 pp. Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Second Edition. Giblin, D.E., B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead (eds). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 882 p.

Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Second Edition. Giblin, D.E., B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead (eds). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 882 p. Jones, Lisa C., Nicholas Norton, and Timothy S. Prather. 2018. Indicators of Ventenata (Ventenata dubia) Invasion in Sagebrush Steppe Rangelands. Invasive Plant Science Management 11:1-9. doi:10.1017/inp.2018/7

Jones, Lisa C., Nicholas Norton, and Timothy S. Prather. 2018. Indicators of Ventenata (Ventenata dubia) Invasion in Sagebrush Steppe Rangelands. Invasive Plant Science Management 11:1-9. doi:10.1017/inp.2018/7 Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Nicolli, Melissa, Thomas J. Rodhouse, Devin S. Stucki, and Matthew Shinderman. 2020. Rapid Invasion by the Annual Grass Ventenata dubia Into Protected-area, Low-elevation Sagebrush Steppe.

Nicolli, Melissa, Thomas J. Rodhouse, Devin S. Stucki, and Matthew Shinderman. 2020. Rapid Invasion by the Annual Grass Ventenata dubia Into Protected-area, Low-elevation Sagebrush Steppe. Poor, E.E., N.J. Kleist, H.L. Bencin, A.C. Foster, and S.K. Carter. 2021. Annotated bibliography of scientific research on Ventenata dubia published from 2010 to 2020. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2021-1031. 26 p.

Poor, E.E., N.J. Kleist, H.L. Bencin, A.C. Foster, and S.K. Carter. 2021. Annotated bibliography of scientific research on Ventenata dubia published from 2010 to 2020. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2021-1031. 26 p. Prather, T., and I. Burke. 2011. Symposium: Ventenata dubia - an emerging threat to agriculture and wildlands? Pages 107-111 in Proceedings of Western Society of Weed Science. Spokane, WA: Western Society of Weed Science.

Prather, T., and I. Burke. 2011. Symposium: Ventenata dubia - an emerging threat to agriculture and wildlands? Pages 107-111 in Proceedings of Western Society of Weed Science. Spokane, WA: Western Society of Weed Science. Prather, Timothy S. 2015. Ventenata dubia (North Africa Grass). CABI Compendium.

Prather, Timothy S. 2015. Ventenata dubia (North Africa Grass). CABI Compendium. Wallace, J., P. Pavek, and T. Prather. 2015. Ecological characteristics of Ventenata dubia in the Intermountain Pacific Northwest. Invasive Plant Science and Management 8:57-71.

Wallace, J., P. Pavek, and T. Prather. 2015. Ecological characteristics of Ventenata dubia in the Intermountain Pacific Northwest. Invasive Plant Science and Management 8:57-71.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Harvey, A.J. 2019. Understanding the biology, ecology, and integrated management of Ventenata dubia. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 117 p.

Harvey, A.J. 2019. Understanding the biology, ecology, and integrated management of Ventenata dubia. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 117 p. Lehnhoff, E.A., L.J.Rew, J.M. Mangold, T. Seipel, and D. Ragen.2019. Integrated management of Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) with sheep grazing and herbicide. Agronomy 9, 315

Lehnhoff, E.A., L.J.Rew, J.M. Mangold, T. Seipel, and D. Ragen.2019. Integrated management of Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) with sheep grazing and herbicide. Agronomy 9, 315 Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Quire, R.L. 2013. The sagebrush steppe of Montana and southeastern Idaho shows evidence of high native plant diversity, stability, and resistance to the detrimental effects of nonnative plant species. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 124 p.

Quire, R.L. 2013. The sagebrush steppe of Montana and southeastern Idaho shows evidence of high native plant diversity, stability, and resistance to the detrimental effects of nonnative plant species. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 124 p. Seipel, T.F. 2006. Plant species diversity in the sagebrush steppe of Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 87 p.

Seipel, T.F. 2006. Plant species diversity in the sagebrush steppe of Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 87 p. Torok, K., A. Horanszky, and G. Kosa. 1994. Long-term changes of species composition in an andesite grassland community of the Visegrad Mountains, Hungary. Abstracta Botanica. Volume 18, Number 1, pp. 13-27

Torok, K., A. Horanszky, and G. Kosa. 1994. Long-term changes of species composition in an andesite grassland community of the Visegrad Mountains, Hungary. Abstracta Botanica. Volume 18, Number 1, pp. 13-27

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Ventenata"