View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Russian Olive - Elaeagnus angustifolia

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Elaeagnus angustifoliais a plant native to the southern Europe and western Asia, and is introduced into North America (Little 1961). A conservation status rank is not applicable (SNA) because the plant is an exotic (non-native) in Montana that is not a suitable target for conservation.

Listed in 2010 Russian Olive is State Regulated by the Montana Department of Agriculture, which means it is illegal to intentionally spread or sell.

NOTE: There is a large discrepancy between the number of observations and counties represented in the herbaria (Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria; www.pnwherbaria.org) versus the Montana Natural Heritage Program databases, which indicates a problem. It is important to document new occurrences with nice quality plant specimens of which some should be deposited in our State herbaria (University of Montana or Montana State University). Depositing specimens in the herbaria allows identifications to be confirmed, provides a central location for educating and sharing information, and the specimens become a source for genetic, morphological, and ecological studies.

General Description

PLANTS: Large shrubs or small trees that grow to 8 meters tall. Stems are thorny with a color and texture that is silvery-mealy becoming orange-brown. Source: Lesica et al. 2012

LEAVES: Alternately arranged. Blades are narrowly lanceolate with smooth (entire) margins, white-mealy, silvery beneath, and 3–10 cm long. Petioles are short. Source: Lesica et al. 2012

INFLORESCENCE: 1-4 stemmed (pedicillate) flowers grow in leaf axils or on short first-year twigs. Flowers have 4-sepals that are silvery on the outside and yellow within, and no petals. Sepals are 2-4mm long. The sepals and stamens form a tube (hypanthium) that surrounds but does not attach to the superior ovary (perigynous). The tube is 5–6 mm long, silvery. The fruit is olive-like, becoming green. Source: Lesica et al. 2012

Phenology

Fruits mature in late summer.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Russian Olive –

Elaeagnus angustifolia, exotic, undesirable, and Regulated:

* Tall shrubs or small trees with twigs that have white-mealy hairs (trichomes), becomeing orange-brown.

* Leaves are alternately arranged, narrowly lanceolate, white-mealy above, and silvery below.

* Twigs have thorns.

* Fruits are silvery-green and dry (olive-like).

American Silverberry –

Elaeagnus commutata, native and desirable:

* Shrubs with twigs that have white-mealy hairs (trichomes), becoming gray.

* Leaves are alternately arranged, ovate to elliptic, white-mealy above, and silvery below.

* Twigs lack thorns.

* Fruits are silvery-green and dry (olive-like).

Silver Buffaloberry -

Shepherdia argentea, native and desirable:

* Shrubs with twigs that have white-mealy hairs (trichomes), becoming gray.

* Leaves are oppositely arranged, oblanceolate, and white-mealy below.

* Twigs have thorns.

* Fruits are orange to red, juicy berries.

Canada Buffaloberry -

Shepherdia canadensis, native and desirable:

* Shrubs with twigs that have brown-mealy hairs (trichomes), becoming gray.

* Leaves are oppositely arranged, narrowly ovate, and brown-mealy below.

* Twigs lack thorns.

* Fruits are orange to red, juicy berries.

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Non-native

Non-native

Range Comments

Russian Olive was introduced into North America during Colonial times (Elias 1980). It was likely introduced as an ornamental, but since the early 1900s it was planted to provide windbreaks and to improve wildlife habitat (Christiansen 1963; Olson and Knopf 1986a and 1986b).

In Montana Russian Olive has been planted as a windbreak since at least 1953 (Lesica and Miles 2001). The earliest Montana specimens documented it in the towns of Bozeman and Missoula in the year 1957 (Posted by April 9, 2019 at http://www.pnwherbaria.org). In 1966 it was documented on the National Bison Range, and labels imply they were not planted (Posted by April 9, 2019 at http://www.pnwherbaria.org).

For maps and other distributional information on non-native species see:

Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Habitat Tool (INHABIT) from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Compendium from the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI)

EDDMapS Species Information EDDMapS Species Information

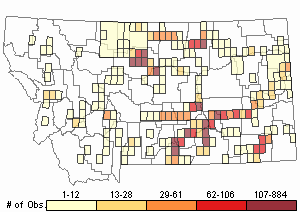

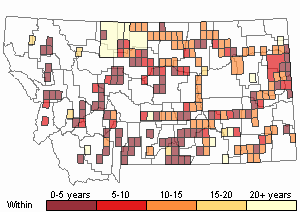

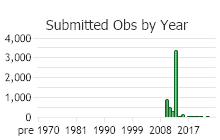

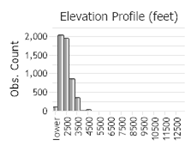

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 5934

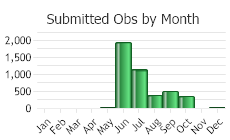

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

In Montana Russian Olive grows in woodlands, thickets, riparian forests, and moist meadows around wetlands in the plains and valleys (Lesica et al. 2012). Plants grow in soils with low to moderate soluble salt concentrations, and are somewhat tolerant of saline soil (Lesica and Miles 2001; Lesica et al. 2012).

Ecology

GROWTH CHARACTERISTICS

Observations of Russian Olive growing in moist, unshaded areas show it will frequently branch at ground level, only 10-20 cm above the surface (Lesica and Miles 2001). While in drier, shaded habitats plants branch well above ground-level. When damaged Russian Olive plants will sprout from the base.

In a study along the Marias and Yellowstone Rivers in Montana the growth rates of Russian Olive plants increased with age, regardless of age class (Lesica and Miles 2001). The relationship was statistically significant for juveniles, but not for mature plants. Growth rates varied from 0.1 to 2.7 cm per year, averaging 0.8 cm per year. Growth rates were greater on sites closer to alluvial ground water than on higher sites.

Russian Olive is a shade tolerant plant, meaning that seeds germinate and growth continues under shady conditions. Studies of older Russian Olive stands show a diversity in age classes indicating that germination is not driven by a disturbance event, such as is needed for cottonwoods. Its large sized fruits facilitate its establishment in shady and moist sites (Lesica and Miles 2001).

Russian Olive plants fix nitrogen in their roots by forming a symbiotic relationship with bacteria in the genus Frankia (Huss-Danell 1997).

PLANT COMMUNITY DYNAMICS

Montana is near the northern limit of Russian Olive’s naturalized range in North America. Russian Olive plants may affect native successional riparian processes in Montana (Lesica and Miles 2001).

Along the Marias and Yellowstone Rivers, Russian Olive was found to only establish on drier high terraces under the presence of a cottonwood overstory (Lesica and Miles 2001). Russian Olive recruitment appears to be facilitated by established cottonwoods. Speculated reasons include that the cottonwood overstory could make micro-climates more humid and cooler, or cottonwoods might help bring water from the water table up to the upper rooting zone through a hydraulic pump. Once Russian Olive is present observations found it will persist as the mature cottonwoods die out. In the absence of Russian Olive, the native succession would have led to a dominance of sagebrush steppe (Boggs 1984).

Annuals riverine floods deposit alluvial materials and change channel morphology creating new habitats conducive for cottonwood regeneration. Many rivers possess regulated flows hinder cottonwood regeneration, but not for Russian Olive. In Montana Russian Olive plants establish under existing groves of cottonwood, and not in adjacent areas indicating that they can change the riparian community but apparently not its extent (Lesica and Miles 2001).

Ecologically Green Ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanicus) and Russian Olive are similar (Lesica and Miles 2001). Green Ash also reproduces under the canopy of cottonwoods. Based on Montana data Russian Olive grows three times faster than Green Ash (Lesica and Miles 2001). This poses a question of whether Russian Olive can or would outcompete Green Ash in Montana.

ANIMAL INTERACTIONS

Beaver

Beaver may prevent cottonwood from developing a mature canopy of trees adjacent to rivers while not hindering the presence of Russian Olives (Lesica and Miles 2001). In a study along the Marias and Yellowstone Rivers beaver were found to damage 57% and 78% of cottonwood trees, respectively, while only damaging 15% and 18% of Russian Olive trees, respectively (Lesica and Miles 2001). The authors also found cottonwood trees were felled at their base while Russian Olive trees only had 1 or 2 basal limbs removed. Further, beaver damage primarily occurred near to active channels on both rivers. This agreed with another observation that Russian Olive plants lined the riverbanks, while cottonwoods were prevalent at greater distances from the rivers.

Birds

Many migratory birds eat Russian Olive fruits and help disperse these plants. In places where Russian Olive replaces cottonwood, cavity-nesting birds do not appear to use Russian Olive and may lose habitat over time (Lesica and Miles 2001).

Ungulates

The frequency (not quantity) of browsing by native and domestic ungulates on Cottonwood and Russian Olive branches was assessed along the Marias and Yellowstone Rivers (Lesica and Mills 2001). No significant difference in preference between Russian Olive or Cottonwood could be discerned; although, it appeared a higher proportion of browsing was found on Cottonwood trees.

Reproductive Characteristics

FLOWER / FRUIT

* Flowers are bisexual or unisexual with a single pistil that has 1 style and 4 or 8 stamens (Lesica et al. 2001).

* Flowers on mature plants produce nectar and edible fruits (Lesica and Miles 2001).

* The Fruit is a solitary achene surrounded by the swollen hypanthium base which becomes mealy, and olive-like (Lesica et al. 2001). With maturity fruits become green, ovoid, and 8-15 mm long.

In a study along the Marias and Yellowstone Rivers in Montana Russian Olive generally began producing fruit at the age from 7-10 years (Lesica and Miles 2001). For trees greater than 10 years in age, 89% of them produced fruit. The average age at which Russian Olive plants first become reproductive is at about 10 years. Taking about 10 years to become reproductive, Russian Olive is considered to have a low recruitment rate.

Seeds germinate under a variety of moisture conditions at different times through the growing season (Lesica and Miles 2001). In greenhouse experiments nearly 90% of seeds from Montana plants germinated and emerged within 30 days when buried to one-inch depth (Hybner and Espeland 2014). However, when seeds were buried to depths of three inches, only a few germinated and none emerged from the soil. The study concluded that deeper buried seeds may lose viability or deteriorate from biotic conditions.

Management

Russian Olive will likely continue to increase along Montana’s rivers because it is immune to beavers, is shade-tolerant, and can colonize a variety of moist habitats in the floodplains along our regulated and free-flowing floodplains. It may likely replace cottonwood trees along rivers where overbank alluvial deposition provides the only establishment for cottonwood seedlings (Lesica and Miles 2001). Russian Olive will tend to become dominant in reaches where the riparian zone is less dynamic and the stream is entrenched or channelized (Lesica and Miles 2001). Eradicating mature Russian Olive trees every 10 years or all trees every 30 years could be an effective strategy to control is populations and affects on native wildlife and plants (Lesica and Miles 2001).

PREVENTIONTo avoid the development of new infestations Russian Olive should not be planted near to riparian areas, overflow areas, or irrigation ditches (Lesica and Miles 2001).

PHYSICAL and CULTURAL CONTROLS Revegetation: Russian Olive is invasive, despite that it has a history of being used in restoration and other improvement-type land projects. There are many alternative species that should be used in conservation plantings and readers should consult

Species Alternatives for Russian Olive in Conservation Plantings (Tober et al. 2006).

CHEMICAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Piper

in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

The herbicide type and concentration, application time and method, environmental constraints, land use practices, local regulations, and other factors will determine its effectiveness and impact to non-target species. Strict adherence to application requirements defined on the herbicide label will reduce risks to human and environmental health. Consult your County Extension Agent and/or Weed District for information on herbicidal control. Chemical information is also available at

Greenbook.

Useful Links:Central and Eastern Montana Invasive Species TeamMontana Invasive Species websiteMontana Biological Weed Control Coordination ProjectMontana Department of Agriculture - Noxious WeedsMontana Weed Control AssociationMontana Weed Control Association Contacts WebpageMontana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks - Noxious WeedsMontana State University Integrated Pest Management ExtensionWeed Publications at Montana State University Extension - MontGuidesStewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Russian Olive is an invasive plant that can out-compete many native plants, especially in wetlands, riparian zones, and saline lowlands.

Where flooding is infrequent, Russian Olive plants establish under native cottonwood stands, eventually out-competing them as the stands age.

Stands of Russian Olive can become dense, suppressing understory vegetation.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Boggs, K. W. 1984. Succession in riparian communities of the lower Yellowstone River, Montana. M.S. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman, 107 pp.

Boggs, K. W. 1984. Succession in riparian communities of the lower Yellowstone River, Montana. M.S. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman, 107 pp. Christiansen, E.M. 1963. Naturalization of Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia L.) in Utah. American Midland Naturalist 70:133-137.

Christiansen, E.M. 1963. Naturalization of Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia L.) in Utah. American Midland Naturalist 70:133-137. Elias, T. B. 1980. The complete trees of North America, field guide and natural history. Book Division, Times Mirror Magazines, Inc. 948 pp.

Elias, T. B. 1980. The complete trees of North America, field guide and natural history. Book Division, Times Mirror Magazines, Inc. 948 pp. Huss-Danell, K. 1997. Actinorhizal symbioses and their nitrogen-fixation. New Phytologist 136: 375-405.

Huss-Danell, K. 1997. Actinorhizal symbioses and their nitrogen-fixation. New Phytologist 136: 375-405. Hybner, Roger, and Erin Espeland. 2014. Russian Olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia L.), Effect of Seed Burial Depth on Seedling Emergence and Seed Viability. Plant Materials Technical Note MT-107, December. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Bozeman, Montana.

Hybner, Roger, and Erin Espeland. 2014. Russian Olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia L.), Effect of Seed Burial Depth on Seedling Emergence and Seed Viability. Plant Materials Technical Note MT-107, December. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Bozeman, Montana. Lesica, P. and S. Miles. 2001. Natural history and invasion of Russian olive along eastern Montana rivers. Western North American Naturalist 61(1):1-10.

Lesica, P. and S. Miles. 2001. Natural history and invasion of Russian olive along eastern Montana rivers. Western North American Naturalist 61(1):1-10. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Little, E.L. 1961. Sixty trees from foreign lands. USDA, U.S. Forest Service, Agriculture Handbook 212, Washington, DC.

Little, E.L. 1961. Sixty trees from foreign lands. USDA, U.S. Forest Service, Agriculture Handbook 212, Washington, DC. McGregor, R.L. (coordinator), T.M. Barkley, R.E. Brooks, and E.K. Schofield (eds). 1986. Flora of the Great Plains: Great Plains Flora Association. Lawrence, KS: Univ. Press Kansas. 1392 pp.

McGregor, R.L. (coordinator), T.M. Barkley, R.E. Brooks, and E.K. Schofield (eds). 1986. Flora of the Great Plains: Great Plains Flora Association. Lawrence, KS: Univ. Press Kansas. 1392 pp. Olson, T. E., and F. L. Knopf. 1986. Naturalization of Russian-olive in the western United States. Western Journal of Applied Forestry 1:65-69.

Olson, T. E., and F. L. Knopf. 1986. Naturalization of Russian-olive in the western United States. Western Journal of Applied Forestry 1:65-69. Olson, T.E., and F.L. Knopf. 1986. Agency subsidization of rapidly spreading exotic. Wildlife Society Bulletin 14:492-493.

Olson, T.E., and F.L. Knopf. 1986. Agency subsidization of rapidly spreading exotic. Wildlife Society Bulletin 14:492-493. Sheley, Roger, and Janet Petroff. 1999. Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon.

Sheley, Roger, and Janet Petroff. 1999. Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon. Tober, Dwight, Craig Stange, and Mike Knudson. 2006. Species Alternatives for Russian Olive in Conservation Plantings. Fact Sheet (Plant Materials), March. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Conservation Service, North Dakota.

Tober, Dwight, Craig Stange, and Mike Knudson. 2006. Species Alternatives for Russian Olive in Conservation Plantings. Fact Sheet (Plant Materials), March. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Conservation Service, North Dakota.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Eggers, M.J.S. 2005. Riparian vegetation of the Montana Yellowstone and cattle grazing impacts thereon. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman, MT. 125 p.

Eggers, M.J.S. 2005. Riparian vegetation of the Montana Yellowstone and cattle grazing impacts thereon. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman, MT. 125 p. Endicott, C.L. 1996. Responses of riparian and stream ecosystems to varying timing and intensity of livestock grazing in central Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 115 p.

Endicott, C.L. 1996. Responses of riparian and stream ecosystems to varying timing and intensity of livestock grazing in central Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 115 p. Fritzen, D.E. 1995. Ecology and behavior of Mule Deer on the Rosebud Coal Mine, Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 143 p.

Fritzen, D.E. 1995. Ecology and behavior of Mule Deer on the Rosebud Coal Mine, Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 143 p. Hale, K.M. 2007. Investigations of the West Nile virus transmission cycle at Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge, Montana, 2005-2006. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 74 p.

Hale, K.M. 2007. Investigations of the West Nile virus transmission cycle at Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge, Montana, 2005-2006. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 74 p. Katz, G. L., and P. B. Shafroth. 2003. Biology, ecology and management of Elaeagnus angustifolia L. (Russian olive) in western North America. Wetlands 23:763-777.

Katz, G. L., and P. B. Shafroth. 2003. Biology, ecology and management of Elaeagnus angustifolia L. (Russian olive) in western North America. Wetlands 23:763-777. Kisch, H.R. 2015. An inventory of carbon stocks under native vegetation and farm fields in south-central Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 67 p.

Kisch, H.R. 2015. An inventory of carbon stocks under native vegetation and farm fields in south-central Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 67 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Lesica, Peter and Scott Miles. 1999. Russian olive invasion into cottonwood forests along a regulated river in north-central Montana. Canadian Journal of Botany, 77:1077-1083.

Lesica, Peter and Scott Miles. 1999. Russian olive invasion into cottonwood forests along a regulated river in north-central Montana. Canadian Journal of Botany, 77:1077-1083. Little, E.L., Jr. 1979. Checklist of United States trees (native and naturalized). Agriculture Handbook No. 541. U.S. Forest Service, Washington, D.C. 375 pp.

Little, E.L., Jr. 1979. Checklist of United States trees (native and naturalized). Agriculture Handbook No. 541. U.S. Forest Service, Washington, D.C. 375 pp. Rauscher, R.L. 1995. Deer use of irrigated alfalfa along the Yellowstone River, Custer County, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 50 p.

Rauscher, R.L. 1995. Deer use of irrigated alfalfa along the Yellowstone River, Custer County, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 50 p. Sater, S. 2022. The insects of Sevenmile Creek, a pictorial guide to their diversity and ecology. Undergraduate Thesis. Helena, MT: Carroll College. 242 p.

Sater, S. 2022. The insects of Sevenmile Creek, a pictorial guide to their diversity and ecology. Undergraduate Thesis. Helena, MT: Carroll College. 242 p. Scow, K.L. 1981. Ecological distribution of small mammals at Sarpy Creek, Montana, with special consideration of the Deer Mouse, Peromyscus maniculatus. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 73 p.

Scow, K.L. 1981. Ecological distribution of small mammals at Sarpy Creek, Montana, with special consideration of the Deer Mouse, Peromyscus maniculatus. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, Montana: Montana State University. 73 p. Shafroth. R B.. G. T. Auble. and M. L. Scott. 1995. Germination and establishment of the native plains Cottonwood (Populits deltoides Marshall subsp. monilifera) and the exotic Russian-olive (Elaeagnvs angustifolia L.). Conservation Biology 9: 1169-1175.

Shafroth. R B.. G. T. Auble. and M. L. Scott. 1995. Germination and establishment of the native plains Cottonwood (Populits deltoides Marshall subsp. monilifera) and the exotic Russian-olive (Elaeagnvs angustifolia L.). Conservation Biology 9: 1169-1175.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Russian Olive"