View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Oxeye Daisy - Leucanthemum vulgare

Other Names:

Dog Daisy, Marguerite,

Chrysanthemum leucanthemum

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Leucanthemum vulgare is a plant native to Europe and introduced into North America (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999). A conservation status rank is not applicable (SNA) because the plant is an exotic (non-native) in Montana that is not a suitable target for conservation activities.

General Description

PLANTS: A rhizomatous perennial forb with erect stems that grow 20-80 cm tall. Plants are glabrous (lacks hairs). Plants have basal and erect stems. Source: Lesica et al. 2012

LEAVES: Basal leaves have long petioles (stalks). Basal leaf blades are spoon-shaped to round and shallowly lobed (crenate). Cauline leaves are alternately arranged, petiolate but become sessile upwards. Sources: Lesica et al. 2012; Davis and Mangold 2018.

INFLORESCENCE: Flower heads are mostly solitary on a long peduncle (flower stem). Flower heads are 1-2 cm wide and have white ray florets and yellow disk florets. Involucral bracts are, unequal, in 2-4 rows, and green with brown scarious margins. The flower head’s receptacle is nearly flat and naked (lacks awns, scales or bristles between the disk florets/achenes). The 15-35 ray florets have white petals of 1-2 cm and are fertile. The numerous disk florets have yellow petals, lack a pappus, are 2-3 mm tall, and have flattened style branches. Sources: Lesica et al. 2012; Davis and Mangold 2018.

TAXONOMY & NOMENCLATURE

The genus Leucanthemum comes from the Greek words leuco- for 'white' and anthemon for 'flower'. The specific epithet vulgare means 'common'.

Phenology

Oxeye Daisy flowers from spring to fall (Strother in Flora of North America (FNA) 2006).

Diagnostic Characteristics

In Montana are 5 non-native species of “daisy” that exhibit the stereotypical appearance of white petals with yellow centers. They are distinguished by the following characteristics:

Oxeye Daisy –

Leucanthemum vulgare, non-native and noxious

* Plants: Rhizomatous perennial. Single, tall stem, 10-30(100+) cm. Overall plants are smaller or slenderer and have lobed basal leaves in comparison to Shasta Daisy.

* Basal Leaves: With long petioles, 1-3 cm. Blades 1.2-3.5 cm long and obovate (widest above middle) to spatulate (spoon) in shape. Leaf pinnately lobed or irregularly toothed less than half-way to their mid-vein.

* Stem (Cauline) Leaves: 1-4 cm long. Margins deeply serrate for their entire length. Becoming sessile upwards.

* Flower Heads: Ray petals 1-2(3) cm long; central disk, 1-2 cm in diameter.

* Involucral Bracts: In 2 to 4 rows, unequal, and with very few hairs (glabrate).

* Habitat: Roadsides, fields, meadows, and often colonizes forest openings and pastures that have been converted from forests.

Shasta Daisy –

Leucanthemum maximum, non-native and cultivated

* Plants: Rhizomatous perennial. Single, tall stem, 20-60(80+) cm. Overall plants grow taller, have larger flowerheads, and lack lobed basal leaves in comparison to Oxeye Daisy.

* Basal Leaves: Always present, 5-8 cm long. With petioles. Blades obovate to lanceolate or linear. Not lobed, but usually shallowly toothed.

* Stem (Cauline) Leaves: May be absent. If present then large, 5-12 cm long with or without petiole, sessile. Blades oblanceolate to elliptic, gradually tapered to petiole. Regularly serrate along the upper margins.

* Flower Heads: Ray petals 2-3 cm long; central disk, 2-3 cm in diameter.

* Involucral Bracts: In 2 to 4 rows, unequal, and with very few hairs (glabrate).

* Habitats: Cultivated plant that is sold for planting into gardens. Rarely has escaped into naturalized areas west of the Cascade Mountains (Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018) or sparingly adventive in Wyoming, California, and Alabama (Strother

inFNA 2006).

Corn Chamomile -

Anthemis arvensis, non-native

* Plants: Taprooted annual. Branched stem, 10-40 cm. Not aromatic.

* Stem (Cauline) Leaves: Finely dissected, 2-3 times pinnately divided from a short petiole.

* Flower Heads: Small, 6-13 cm in diameter.

* Involucral Bracts: In 3-5 rows, with scarious margins and long, soft, crooked,

and unmatted (villous) hairs.

* Habitat: Fields and roadsides. From a 1908 herbarium specimen in Lake County (Lesica et al. 2025).

Mayweed -

Anthemis cotula, non-native

* Plants: Taprooted annual. Single or branched stem, 10-60 cm. Aromatic (ill-scented).

* Stem (Cauline) Leaves: Finely dissected, 2-3 times pinnately divided from a short petiole.

* Flower Heads: Small, 5-9 mm in diameter.

* Involucral Bracts: In 3-5 rows, with scarious margins and sparsely villous hairs.

* Habitat: Fields and roadsides.

Lawn Daisy -

Bellis perennis, non-native and undesirable

* Plants: Annual with fibrous roots. Single, short stem, 5-15 cm.

* Basal Leaves: 2-6 cm long and with petioles. Blades spatulate (spoon) shaped. Margins smooth (entire) to toothed.

* Stem (Cauline) Leaves: Absent.

* Involucral Bracts: In 1 row, narrowly ovate, and with hairs (strigose).

* Habitat: Lawns (Montana; Lesica et al. 2022). Moist, waste places and roadsides (North America; Brouillet

in FNA 2006).

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Non-native

Non-native

Range Comments

Oxeye daisy is presumed native to Europe, British Isles, northern Scandinavia, Lapland, and central and Russian Asia (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999). It appeared in Britain during the post-glacial period and has been identified from the Iron Age (about 1200-550 B.C.) and Roman periods. It was brought to North America and New Zealand as a contaminant in seed. It was also introduced as an ornamental plant (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999). It has escaped cultivation and is presumably found in every U.S. state and Canadian province (NRCS PLANTS database; https//plants.usda.gov). Because it is a pretty flower, many landowners do not mow the plants as they appear in their lawns and fields [see also Management / Grazing Control]. Of course, this has helped to boost their populations and distribution across North America.

In Montana Oxeye Daisy was documented in the Montana Territory in 1883 (OSC specimen). Herbarium specimens collected by different people documented its first Montana appearances in 1900, 1901, and 1903 from Flathead, Gallatin, and Carbon Counties, respectively (Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria; www.pnwherbaria.org).

Adhikari et al. (2020) modeled the predicted future distribution of this and other weed species across the major road network in Montana under predicted future climate scenarios and found that area of predicted future habitat suitability is likely to increase.

For maps and other distributional information on non-native species see:

Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Habitat Tool (INHABIT) from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Compendium from the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI)

EDDMapS Species Information EDDMapS Species Information

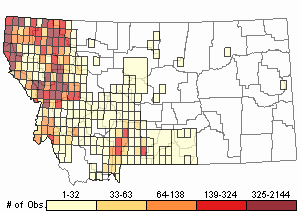

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

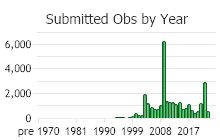

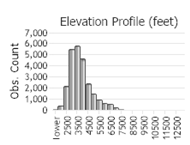

Number of Observations: 31760

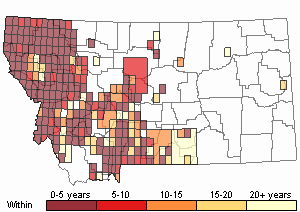

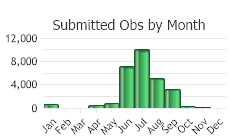

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

In Montana Oxeye Daisy grows mostly in moist area along roadsides and in fields, meadows, forest openings, and pastures converted from forest in the valleys to montane zones (Lesica et al. 2012). Elsewhere it is also found along railroad embankments and waste areas.

Ecology

Oxeye Daisy is a strong competitor that forms dense populations, especially in pastures (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Oxeye Daisy has a small taproot and shallow, branching rhizomes which can replace the often large fibrous root system of grasses (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999). This can lead to an increase in soil erosion, particularly along waterways. To establish, it is thought that Oxeye Daisy needs some vegetative disturbance. Oxeye Daisy does not germinate well in relatively thick litter layers, but easily germinate on bare soil.

Oxeye daisy has wide tolerance to soil conditions, but grows best in soils ranging from a pH of 6.5-7.0 (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999). It is more commonly found on alkaline (basic) or neutral soils and less often on acidic soils. It grows well on both nutrient-rich and -poor soils. It has a moderate requirement for nitrogen. A study found that plants grown under low nutrient levels, allocated more biomass to the root system and less biomass to flowering (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999). It has been observed to be more prolific on poorer soils, which may not indicate a preference, but could indicate that it does not compete as well with established plants on fertile soil (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999).

Light can affect reproduction, whereas soil nutrient levels did not. A study found that shaded plants allocated more resources to flowering, suggesting it is a strategy to maximize their seed production (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999).

Oxeye Daisy is usually found in moist areas, but it tolerates droughts (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999). It is a pioneer species in some habitats exposed to drying soil conditions. Where water stressed, the deeper-rooting Common Dandelion has been found to wilt before Oxeye Daisy. Seedlings are considered drought tolerant.

GRAZING [Adapted from Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Horses, sheep and goats will graze Oxeye Daisy, while cattle and pigs avoid it because it is acrid.

In a study where Oxeye Daisy made up 20% of the plant community, it greatly increased under continuous cattle grazing (Norman 1957). Under rotation grazing by cattle or close rotational and continuous grazing by sheep it increased less.

In a study in southwestern Montana, high cattle densities for short time periods were used to examine if cattle could overcome the tendency to avoid Oxeye Daisy. Two years of intensive grazing reduced seedling and rosette stages, but had no effect on adult Oxeye Daisy plants when compare with adjacent, ungrazed exclosures. It was also observed that cows would pull up mature adult plants, but not eat them probably because of its acridity.

When cows remove the inflorescence, many lateral stems quickly develop. It was found that less than 40% of seeds remain viable if passed through the digestive system of a cow.

CULTURAL

Oxeye Daisy is used as good by humans; Italians use it in salads (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999).

Reproductive Characteristics

Plants reproduce by seeds and rhizomes.

ROOTS

Oxeye Daisy has a small taproot, branched rhizomes, and adventitious roots. The prostrate stems easily root. Branched rhizomes grow shallow in the soil profile.

FRUITS

Fruit is an achene. Achenes are cylindric, 1-3 mm long, ribbed, and glabrous (Lesica et al. 2012).

Plants produce an abundance of seeds, from 1,300 to 4,000 seeds per small plant to 26,000 seeds per vigorous plant (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999).

LIFE CYCLE [Adapted from Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Germination typically occurs in the spring, but can occur throughout the growing season. Germination is not reliant on particular conditions of light, nitrates, chilling, or seed coat scarification (sulphuric acid treatment). Upon germination a pair of cotyledons is produced above the soil surface. They wither when the first true-leaf develops at the soil surface. At about the 6-leaf stage, the primary root starts to be replaced by a system of lateral roots which grow shallowly. The main root loses its importance as the rhizomes develop. Perennating buds at the soil surface on the rhizome are protected by snow or organic debris (hemicryptophyte).

The “juvenile” stage of development is marked by a rosette of basal leaves. An individual plant can bear one to many rosettes on the ground surface. Each rosette typically produces one flowering stem. Thus, through time plants produce a dense mat of rosettes.

Plants flower from spring to fall. Seeds mature 10 days after flowers open (Georgia 1914), thus there is no dormancy period. Seed viability is long-lived. A study found that 82% of buried seeds were viable after 6 years and 1% of them were viable after 39 years.

DISPERSAL

Seeds lack a pappus which reduces the distance that wind can carry them. Hence, seeds often land near to their parents. Seeds can be carried in the fur of livestock and other animals. Seeds can easily contaminate grass seed, which has been a means of dispersal in the U.S.

Management

An integrated vegetative management approach provides the best long-term control of Oxeye Daisy. It requires that land-use objectives and a desired plant community be identified (Shelly et al.

in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Once identified the integrated weed management strategy can promote a weed-resistant plant community and serves other land-use objectives such as livestock forage, wildlife habitat, or recreation can be developed, making control of Oxeye Daisy possible.

PREVENTIONOxeye Daisy is often encouraged as an ornamental to plant, and has been found in numerous seed mixes. Users should carefully read packaging labels and not purchase if its scientific names or common names or any synonyms are listed.

Seed development must be prevented to reduce or stop spread.

* Prevent vehicles from driving through and animals from grazing within infested areas,

* Thoroughly wash the undercarriage of vehicles and wheels in a designated area before moving to an uninfested area,

* Encourage landowners to frequently monitor their land for new infestations and, when found to implement effective control methods.

* Maintain proper livestock grazing management to encourage competitive vegetation, and

* Develop educational campaigns to teach people to not pick and transport the white flowers.

PHYSICAL and CULTURAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Olson and Wallander

in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Hand-pulling can be effective for small or new infestations. It should be done before plants have flowered. Gloves should be worn to protect skin. Plants should be bagged, allowed to desiccate or rot, and then be deposited in the landfill.

mowing as soon as flower buds develop is effective to reduce seed production. However, mowing will stimulate shoot production, and subsequent flowering could occur if conditions are good. Not mowing fields with Oxeye Daisy is also not a good control method because over-time Oxeye Daisy will likely succeed.

Tilling that is repeated in the same growing season can kill plants because rhizomes grow shallow in the soil profile. Seeds in the seedbank will germinate, and require follow-up treatment.

GRAZING CONTROLS [Adapted from Olson and Wallander

in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Horses, sheep and goats will graze Oxeye Daisy, while cattle and pigs avoid it because it is acrid.

Information on how horses, sheep, or goats can be used to control Oxeye Daisy was not found.

Horses, sheep, and goats that graze where Oxeye Daisy grows should be retained in a holding pen before moving into uninfested areas.

Grazing management that maintain vigorous growth of desirable plants will help compete against Oxeye Daisy.

CHEMICAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Olson and Wallander

in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

The herbicide type and concentration, application time and method, environmental constraints, land use practices, local regulations, and other factors will determine its effectiveness and impact to non-target species. Strict adherence to application requirements defined on the herbicide label will reduce risks to human and environmental health. Consult your County Extension Agent and/or Weed District for information on herbicidal control. Consult your County Extension Agent and/or Weed District for more information on herbicidal control. Chemical information is also available at

Greenbook.

Oxeye daisy is moderately resistant to some

2,4-D-based herbicides except at high rates of 5 pounds per acre.

One study found that applying 80 pounds of

nitrogen fertilizer was a more cost-effective treatment after 7 years that using herbicide alone or in combination with fertilizer. The treatment increased grass yields by 500% over this time. Herbicides can kill plants, while fertilizers promote growth of desirable forage.

Picloram (1.5 pint per acre) mixed with

2,4-D (1 quart) per acre was applied to a heavily infested Oxeye Daisy site in 1990. The treatment provided 100% control, but is not recommended to use for a long-term control method. Herbicides often have to be re-applied every 2-3 years because of the seed bank.

The seed bank and long length of seed viability will allow Oxeye Daisy to return for many years. Therefore, control methods that encourage the growth of vigorous, competitive desirable plants is recommended.

BIOLOGICAL CONTROLS [Adapted from Jacobs et al. 2015]

Currently no biological control agents are available.

Useful Links:Montana Invasive Species websiteMontana Biological Weed Control Coordination ProjectMontana Department of Agriculture - Noxious WeedsMontana Weed Control AssociationMontana Weed Control Association Contacts Webpage.

Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks - Noxious WeedsMontana State University Integrated Pest Management ExtensionWeed Publications at Montana State University Extension - MontGuidesStewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Oxeye Daisy reduces plant species diversity (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999). It colonizes fields and aggressively out-competes other vegetation to form dense populations. In areas grazed by cattle, Oxeye Daisy is usually avoided because it is acrid. Thus, this allows the plant to flourish and reduces forage availability for cattle.

Grasses often have a large fibrous root system, but can be replaced by Oxeye Daisy that has a small taproot (Olson and Wallander in Sheley and Petroff 1999). This can increase soil erosion, particularly along waterways.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Adhikari, A., L.J. Rew, K.P. Mainali, S. Adhikari, and B.D. Maxwell. 2020. Future distribution of invasive weed species across the major road network in the state of Montana, USA. Regional Environmental Change 20(60):1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01647-0

Adhikari, A., L.J. Rew, K.P. Mainali, S. Adhikari, and B.D. Maxwell. 2020. Future distribution of invasive weed species across the major road network in the state of Montana, USA. Regional Environmental Change 20(60):1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01647-0 Flora of North America Editorial Committee. 2006. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 19. Magnoliophyta: Asteridae, part 6: Asteraceae, part 1. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. xxiv + 579 pp.

Flora of North America Editorial Committee. 2006. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 19. Magnoliophyta: Asteridae, part 6: Asteraceae, part 1. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. xxiv + 579 pp. Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Second Edition. Giblin, D.E., B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead (eds). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 882 p.

Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Second Edition. Giblin, D.E., B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead (eds). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 882 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Sheley, Roger, and Janet Petroff. 1999. Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon.

Sheley, Roger, and Janet Petroff. 1999. Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Culver, D.R. 1994. Floristic analysis of the Centennial Region, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 199 pp.

Culver, D.R. 1994. Floristic analysis of the Centennial Region, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 199 pp. Flora of North America Editorial Committee (FNA). 2006. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 21. Magnoliophyta: Asteridae (in part): Asteraceae, part 3. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. xxii + 616 pp.

Flora of North America Editorial Committee (FNA). 2006. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 21. Magnoliophyta: Asteridae (in part): Asteraceae, part 3. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. xxii + 616 pp. Meier, G.A. 1997. The colonization of Montana roadsides by native and exotic plants. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 45 p.

Meier, G.A. 1997. The colonization of Montana roadsides by native and exotic plants. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 45 p. Olliff, Tom, Roy Renkin, Craig McClure, Paul Miller, Dave Price, Dan Reinhart, and Jennifer Whipple. 2001. Managing A Complex Exotic Vegetation Program in Yellowstone National Park.

Olliff, Tom, Roy Renkin, Craig McClure, Paul Miller, Dave Price, Dan Reinhart, and Jennifer Whipple. 2001. Managing A Complex Exotic Vegetation Program in Yellowstone National Park. Rens, E.N. 2003. Geographical analysis of the distribution and spread of invasive plants in the Gardiner Basin, MT. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 100 p.

Rens, E.N. 2003. Geographical analysis of the distribution and spread of invasive plants in the Gardiner Basin, MT. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 100 p. Schwend, Ann C. 1995. Sclerotium spp for biological control of tall larkspur (Delphinium spp). M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 98 p.

Schwend, Ann C. 1995. Sclerotium spp for biological control of tall larkspur (Delphinium spp). M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 98 p. Tuinstra, K. E. 1967. Vegetation of the floodplains and first terraces of Rock Creek near Red Lodge, Montana. Ph.D dissertation. Montana State University, Bozeman 110 pp.

Tuinstra, K. E. 1967. Vegetation of the floodplains and first terraces of Rock Creek near Red Lodge, Montana. Ph.D dissertation. Montana State University, Bozeman 110 pp.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Oxeye Daisy"