View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Orange Hawkweed - Hieracium aurantiacum

Other Names:

Devil's Paint Brush, Devil's Paintbrush, Fox and Cubs,

Pilosella aurantiaca

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Hieracium aurantiacum is a plant native to Europe and introduced to most of the non-arid areas of temperate North America (Lesica et al. 2012). A conservation status rank is not applicable (SNA) because the plant is an exotic (non-native) in Montana that is not a suitable target for conservation activities.

General Description

PLANTS: Perennial forbs with erect stems from 10-35 (70) cm tall that are rhizomatous and stoloniferous. Rhizomes have fibrous-roots. Stems are single (simple). Stems have stiff hairs (hirsute) of 2-4+ mm that may become shorter and stipitate-glandular upwards. Sources: FNA 2006; Lesica et al. 2012.

LEAVES: 3-8 basal leaves and 0-1 stem leaf. Basal leaves 3-15 cm long, petiolate, blades spatulate to oblanceolate, margins entire, and tips acute. Leaf surfaces with stiff hairs (hirsute) of 1-2+ mm long and stellate-pubescent.

INFLORESCENCE: More-or-less umbelliform. Burnt orange flower heads of 3 to 12, clustered, and pedunculate with stellate pubescence and stipitate-glandular hairs. The involucres are campanulate, 5–9 mm high. The involucral bracts (phyllaries) are linear-lanceolate with acuminate tips, and are stellate-hairy, stipitate-glandular, and sparsely setose-hirsute. Flower heads composed of 25 to 100 florets with petals red to orange, 6–8 mm long. The pappus are white bristles of 3.5-4 mm long. Fruits (cypselae) are columnar, about 2 mm long, and retain the tuft of bristles (pappus).

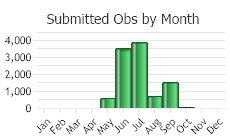

Phenology

Flowering May – September (FNA 2006).

Diagnostic Characteristics

Montana has about 4 native and 3 exotic species of hawkweeds.

Orange Hawkweed is the only hawkweed in Montana with red-orange flower heads. Flower heads are composed of only ray florets.

Orange Agoseris Agoseris aurantiaca also has orange to pink, ligulate flower heads, but the plants are not hirsute hairy and the basil leaves are larger and oblanceolate. It grows in meadows and rocky slopes.

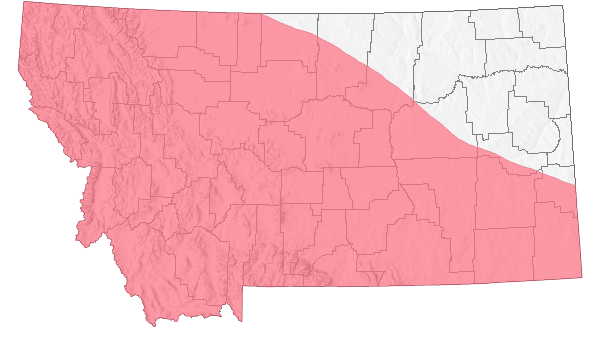

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Non-native

Non-native

Range Comments

Native to northern and central Europe, Orange Hawkweed was introduced into Vermont in 1875 as an ornamental (Wilson and Callihan in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Across the northern U.S. it was planted in gardens, cemeteries, and other landscapes, where it often escaped. It took about 25 years to spread through most of New England east to Michigan and into adjacent Canada (Wilson and Callihan in Sheley and Petroff 1999). By the 1920s it was found in Oregon (www.pnwherbaria.org). It has now been introduced to most of the non-arid, temperate region of North America (Lesica et al. 2012).

For maps and other distributional information on non-native species see:

Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Habitat Tool (INHABIT) from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Compendium from the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI)

EDDMapS Species Information EDDMapS Species Information

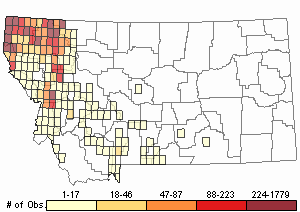

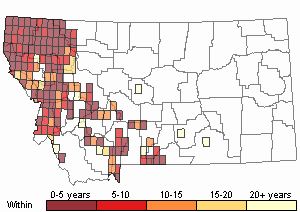

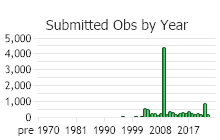

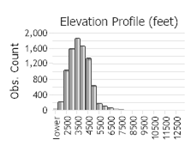

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 12253

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Disturbed soil of forest openings, rock slides, roadsides, lawns; valleys to lower subalpine (Lesica et al. 2012).

Ecology

The loss of biodiversity is the most prevalent threat posed by Orange Hawkweed.

HABITAT VULNERABILITY

In their native habitats of northern and central Europe, Meadow and Orange Hawkweeds are species of pastures, roadsides, abandoned fields, and meadows that form small populations (Skalinksa 1967). In the northern U.S. these plants appear to pose the greatest threat to cooler, sub-humid to humid habitats.They have invaded moist pastures, forest meadows, abandoned fields, clearcuts, and roadsides from valleys to montane (Skalinksa 1967; Lesica et al. 2012). These habitats that also have well-drained, coarse-textured soils low in organic matter appear the most vulnerable to invasion by Orange Hawkweed (Wilson and Callihan

in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Once established plants quickly grow into a matt of dense rosettes (Wilson and Callihan

in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Consequently, elk habitat, recreational areas, and pristine mountain meadows are especially susceptible to invasion (Wilson and Callihan

in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Drier rangeland habitats are not suspected of being vulnerable (Wilson and Callihan

in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Meadow and Orange Hawkweeds apparently do not survive in annually-tilled cropland (Wilson and Callihan

in Sheley and Petroff 1999).

POLLINATORS The following animal species have been reported as pollinators of this plant species or its genus where their geographic ranges overlap:

Bombus ternarius,

Bombus terricola,

Bombus bohemicus, and

Bombus flavidus (Heinrich 1976, Colla and Dumesh 2010).

Reproductive Characteristics

Orange Hawkweed plants reproduce by seed, rhizomes, and stolons.

From the rosette, plants produce one flowering stem. Plants are often apomictic, that is reproducing from asexually produced seeds (FNA 2006). Apomictic reproduction creates morphological variants that perpetuate at population and regional levels (FNA 2006). This can make identifying hybrids difficult. Very few seeds are produced sexually through pollination and out-crossing (Wilson and Callihan in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Flowering in a related species, Hieracium floribundum, was found to occur upon exposure to a specific amount and quality of light (Wilson and Callihan in Sheley and Petroff 1999).

Mature seeds can germinate immediately after dispersal and be viable for up to seven years (Wilson and Callihan in Sheley and Petroff 1999). In a study of Hieracium floribundum only 1% of new plants were born from seeds (Thomas and Dale 1974). The study also found that 80% of the seeds dispersed within the colony with only 1% of the seeds travelling greater than 30 feet (10 meters) from the patch. Another study found seedlings that germinated in spring had better survival rates than those germinating in summer or winter (Johnson and Thomas 1978).

Management

PREVENTION [Adapted from Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Successful management seeks to prevent infestations and detect them before the patch spreads vegetatively. Large infestations are difficult to control. Using multispectral, digital images may identify infestations in remote areas better than visual surveys over large areas (refer to Carson et al. 1995).

CHEMICAL CONTROL The Phenoxy-type herbicides (2,4-D, clopyralid, and picloram) are effective in controlling orange and meadow hawkweeds when applied to the rosette stage and used with a surfactant (Wilson and Callihan

in Sheley and Petroff 1999). The herbicide type and concentration, timing of chemical control, soil properties, and other factors will determine its effectiveness and impact to non-target species. Strict adherence to application requirements defined on the herbicide label will reduce risks to human and environmental health. Many herbicides must be applied by applicators with an Aquatic Pest Control license. Consult your County Extension Agent and/or Weed District for more information on herbicidal control.

Greenhouse and field studies conducted in southern Alaska by the Agricultural Research Service examined the effectiveness of aminopyralid, clopyralid, picloram, picloram+chlorsulfuron, picloram+metsulfuron, and triclopyr herbicides in controlling orange hawkweed (Seefeldt and Conn 2011). Only

aminopyralid at 105 g ai/ha and

clopyralid at 420 g ai/ha controlled orange hawkweed consistently, with peak injury observed one year after treatment. Clopyralid had less impact on non-target species with most recovering the year after treatment. In a pasture system, where grasses are preferred to forbs and shrubs, aminopyralid is preferred because it controls a broader array of forbs compared to clopyralid. In natural areas, where the desire is to retain biodiversity and the aesthetics of multiple forb, grass, and willow species, clopyralid is preferred because it will leave a greater species diversity than aminopyralid.

Researchers at the University of Idaho found more than a 50% control of hawkweed using

clopyralid at the rate of 0.5 lb ai/ac (Wilson and Callihan

in Sheley and Petroff 1999). A similar control was found using

picloram at the rate of 0.2-0.5 lb ai/ac.

A combination of fertilizers and herbicides applied to areas where hawkweed is mixed with perennial grasses, legumes, and other forbs can reduce spreading (Wilson and Callihan

in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Fertilizer treatments reduced hawkweed density and vigor in the U.S., Canada, and New Zealand. Depending upon soil productivity and grass condition, fertilizers can promote the growth of desirable plants which may become competitive enough to suppress hawkweed growth.

CULTURAL & GRAZING CONTROLS [Adapted from Wilson and Callihan

in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

Hand-pulling and

mowing are not effective control measures. Physical disturbance to orange hawkweed severs roots, stolons, and/or rhizomes causing the plant to further spread. Mowing may remove flowering stems and reduce seed production but will not hinder growth by the stolons or rhizomes. Soils disturbed by livestock, rodents, or people can also enhance the plant to spread.

BIOCONTROL [Adapted from Wilson and Callihan

in Sheley and Petroff 1999]

In 1995 the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Bozeman, Montana began to develop the feasibility of a biological control program for orange and meadow hawkweeds. However, biological control for these plants has not yet successfully been developed in the U.S.

Useful Links:Central and Eastern Montana Invasive Species TeamMontana Invasive Species websiteMontana Biological Weed Control Coordination ProjectMontana Department of Agriculture - Noxious WeedsMontana Weed Control AssociationMontana Weed Control Association Contacts WebpageMontana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks - Noxious WeedsMontana State University Integrated Pest Management ExtensionWeed Publications at Montana State University Extension - MontGuides

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

The loss of biodiversity is the most prevalent threat posed by Orange Hawkweed.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Carson, H.W., L.W. Lass, and R.H. Callihan. 1995. Detection of Yellow Hawkweed with high resolution digital images. Weed Technol. 9: 477-483.

Carson, H.W., L.W. Lass, and R.H. Callihan. 1995. Detection of Yellow Hawkweed with high resolution digital images. Weed Technol. 9: 477-483. Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68.

Colla, S.R. and S. Dumesh. 2010. The bumble bees of southern Ontario: notes on natural history and distribution. Journal of the Entomological Society of Ontario 141:39-68. Flora of North America Editorial Committee. 2006. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 19. Magnoliophyta: Asteridae, part 6: Asteraceae, part 1. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. xxiv + 579 pp.

Flora of North America Editorial Committee. 2006. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 19. Magnoliophyta: Asteridae, part 6: Asteraceae, part 1. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. xxiv + 579 pp. Johnson, C.D., and A.G. Thomas. 1978. Recruitment and survival of seedlings of perennial Hieracium species in a patchy environment. Can. J. Bot. 56: 572-580.

Johnson, C.D., and A.G. Thomas. 1978. Recruitment and survival of seedlings of perennial Hieracium species in a patchy environment. Can. J. Bot. 56: 572-580. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Seefeldt, Steven, and Jeffery Conn. 2011. Control of Orange Hawkweed (Hieracium aurantiacum) in Southern Alaska. Journal of Invasive Plant Science and Management 4(1): 87-94.

Seefeldt, Steven, and Jeffery Conn. 2011. Control of Orange Hawkweed (Hieracium aurantiacum) in Southern Alaska. Journal of Invasive Plant Science and Management 4(1): 87-94. Sheley, Roger, and Janet Petroff. 1999. Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon.

Sheley, Roger, and Janet Petroff. 1999. Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon. Skalinska, M. 1967. Cytological analysis of some Hieracium species, subgenus Pilosella, from mountains of southern Poland. Acta. Biol. Cracov. Ser. bot. 10: 128-141.

Skalinska, M. 1967. Cytological analysis of some Hieracium species, subgenus Pilosella, from mountains of southern Poland. Acta. Biol. Cracov. Ser. bot. 10: 128-141. Thomas, A.G., and H.M. Dale. 1974. Zonation and regulation of old pasture populations of Hieracium floribundum. Can. J. Bot. 52:1451-1458.

Thomas, A.G., and H.M. Dale. 1974. Zonation and regulation of old pasture populations of Hieracium floribundum. Can. J. Bot. 52:1451-1458.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Simanonok, M. 2018. Plant-pollinator network assembly after wildfire. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 123 p.

Simanonok, M. 2018. Plant-pollinator network assembly after wildfire. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 123 p. Simanonok, M.P. and L.A. Burkle. 2019. Nesting success of wood-cavity-nesting bees declines with increasing time since wildfire. Ecology and Evolution 9:12436-12445.

Simanonok, M.P. and L.A. Burkle. 2019. Nesting success of wood-cavity-nesting bees declines with increasing time since wildfire. Ecology and Evolution 9:12436-12445.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Orange Hawkweed"