View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Concentric Ring Lichen - Arctoparmelia centrifuga

Other Names:

Rippled Rockfrog, Rippled Ring Lichen,

Xanthoparmelia centrifuga

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Arctoparmelia centrifuga is restricted to boreal and arctic regions in North America where it can be common or abundant, but south of Canada it becomes very rare. In Montana it is known from two widely scattered locations in the western portion of the state. Arctoparmelia centrifuga grows where there is cold-air drainage at the base of talus slopes comprised of acidic rock. Precise mapping and current data on known locations, population parameters, threats, trends, habitat conditions, and other information is needed.

General Description

GROWTH FORM: Foliose

THALLUS: Medium to large, stratified, and with an upper and lower cortex. Lobes closely appressed, elongate, narrow, and mostly 0.3-0.5 mm wide. Upper surface pale yellowish green, dull. Medulla white. Lower surface pale colored, whitish to tan, and velvety (pruinose). Rhizines short, single, and scattered. Sources: Goward et al. 1994; McCune and Geiser 2023

PHOTOBIONT: Green-algal. Layer appears brighter green. Source: Goward et al. 1994

REPRODUCTIVE TYPES: Apothecia. Sources: Goward et al. 1994; McCune and Geiser 2023

CHEMICAL REACTIONS: Cortex K+ pale yellow, KC+ yellow, UV+. Medulla UV+ white, C+ slowly yellow, KC+ reddish

TAXONOMY & NOMENCLATURE

The large and diverse Parmeliaceae family has been revised three times by Mason Hale (1929-1990), premier lichenologist with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC (Wikipedia 2025a). Within this family, Hale became a leading expert on the genus Parmelia, which once included lichens of great morphological differences (Wikipedia 2025b). In 1974, Hale established the genus Xanthoparmelia (Vain.) Hale to separate out the "obligate saxicolous, epicorticate, usnic-acid containing lichen species" that were formerly classified under Parmelia (Hale 1986). In 1986 Hale established the genus Arctoparmelia Hale to separate from Xanthoparmelia the species that have a velvety, ivory-white to purplish lower surface, contain alectoronic acid, and are restricted to arctic-boreal regions (Hale 1986).

Arctoparmelia species are also called the Rockfrog Lichens, in reference to their green upper surface and strict association with rocks (Goward et al. 1994). The authors suggested Rippled Rockfrog as the common name for Arctoparmelia centrifuga.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Arctoparmelia and

Xanthoparmelia species are superficially similar, but differ in their chemistry, lower surface, and lobe width (McCune and Geiser 2023).

Arctoparmelia* Upper Surface: Often dull.

* Lower Surface: Often velvety from apparent pruinosity

* Chemistry: Cortex KC+ yellow

* Lobes: Closely appressed to substrate. Elongate and narrower, often averaging 0.5 mm wide or less.

Xanthoparmelia* Upper Surface: Often shiny or with a sheen.

* Lower Surface: Somewhat shiny; not velvety.

* Chemistry: Cortex K-

* Lobes: Tightly appressed to semi-erect. Elongate and wider, 0.5-5.0 mm.

IDENTIFYING ARCTOPARMELIA SPECIESArctoparmelia centrifuga - Concentric Ring Lichen, SOC

* Upper Surface: Firm cortex

* Lobes: Rarely turned downwards at tips.

* Reproduction: Lacking soredia

Arctoparmelia subcentrifuga - Subcentric Ring Lichen, SOC

* Upper Surface: Soft cortex that appears to erode.

* Lobes: Often turned downwards at tips.

* Reproduction: Soredia present and diffuse on the upper surface.

Arctoparmelia incurva - Subcentric Ring Lichen, NOT DOCUMENTED

* Upper Surface: Firm cortex

* Reproduction: Soredia present in discrete, roundish soralia.

* Lower Surface: Dark.

* Distribution: It could be found in Montana as the nearest occurrence is in British Columbia, Canada.

Range Comments

Arctoparmelia centrifuga is a circumpolar, arctic alpine lichen that extends from Alaska south to central British Columbia and east to Atlantic provinces and states in Canada and the USA (Brodo 2001). Occurrences in Montana are likely the southern-most populations – perhaps disjunct populations.

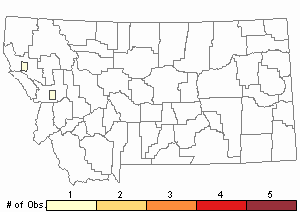

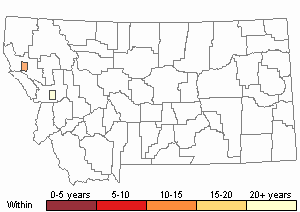

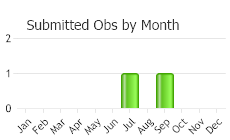

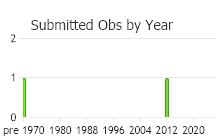

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 2

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Arctoparmelia centrifuga grows on acidic or somewhat base-rich rock in open inland sites, especially boulderbeds (Goward 1994). In Montana, these lichens are found where there is cold air-drainage at the base of north-facing coarse talus slopes (McCune and Geiser 1993). Known also as “slide-rock coolers” by early Anglo-American settlers, winter moisture penetrates deeply into the talus where it freezes and gradually thaws in the summer (McCune et al. 2014). Air in contact with the buried ice and cold rock seeps out along the base of the talus. Recreationalists recognize these areas by the cool air they feel on hot summer days. These habitats are important refugia for northern species.

In a study of the Jonas Rockslide in Alberta, Canada, Arctoparmelia centrifuga was found to grow on steep rock surfaces (John 1989). The study found that steep rockfaces tend to receive less solar radiation than shallow rockface slopes, especially if north-facing. Steep rockfaces are drier because snow is not retained, less precipitation is received, and runoff is faster.

Ecology

CHEMICAL COMPOUNDS

Lichens produce primary and secondary chemical compounds that provide a variety of essential and specialized roles (McCune and Geiser 2023). Readers are encouraged to consult Nash (1996) and McCune and Geiser (2023) for more information.

Compounds found in Arctoparmelia centrifuga include: atranorin and usnic acids in the cortex and alectoronic acid in the medulla (Goward et al. 1994).

TALUS SLOPE-LICHEN COMMUNITY

Rock loving lichens (saxicolous) can exhibit species-specific microhabitat requirements and be sensitive to the microclimate conditions (John 1989). This is partially because of their small size, intimate relationship with their substate, and a relative lack of regulatory mechanisms to control their temperature and water loss. Rocks absorb little moisture and exhibit large fluctuations in temperature on a daily and seasonal basis. The spatial pattern of saxicolous lichens was studied at the Jonas Rockslide in Jasper National Park, Alberta (John 1989). Of the 106 saxicolous lichen species found on the rockslide, lichen coverage was 87%. Growth forms were composed of: 47% crustose, 15% foliose, 9% umbilicate, 7% fruticose, and 6% filamentous. In this system, mosses had less than 1% cover. In general, the high light environment coincided with a darker colored thallus and apothecia and a greater degree of pruinosity when individuals of a given species were compared to those in less exposed habitats. They also found that the erosive power of wind coincided with eroded and depauperate thalli when growing in high light talus slopes, particularly for foliose species. Although some species are generalists, many lichen species tended to associate with specific microhabitats, including crevices and overhangs; exposed edges; rock face centers with low slopes; steep rock surfaces; sheltered rock surfaces; periodically flooded rock; and newly exposed rock surfaces. Arctoparmelia centrifuga was found to grow on steep rock surfaces – see Habitat for more details.

Reproductive Characteristics

Arctoparmelia subcentrifuga lacks vegetative (asexual) diapsores. Sexual reproduction of the fungus occurs by spores produced from apothecia.

GENERATIVE REPRODUCTION

Apothecia are cup- or disk-shaped fruiting bodies on the thallus in which spores, sexual reproduction of the fungus, develop (Budel and Scheidegger in Nash [ed.] 1996). Species of Arctoparmelia produce apothecia with brown discs on the upper surface of the thallus and spores are simple, ellipsoid, and colorless; 8 per ascus (Goward et al. 1994).

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Climate change may be a threat to the habitat of Arctoparmelia centrifuga.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Brodo, Irwin M., Sharnoff, Sylvia D. and Stephen Sharnoff. 2001. Lichens of North America. Yale University Press. New Haven and London. 795 pp.

Brodo, Irwin M., Sharnoff, Sylvia D. and Stephen Sharnoff. 2001. Lichens of North America. Yale University Press. New Haven and London. 795 pp. Goward, Trevor, Bruce McCune, and Del Meidinger. 1994. The Lichens of British Columbia. Illustrated Keys, Part 1-Foliose and Squalmulose Species. Special Report Series 8. Ministry of Forests Research Program. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. ISSN 0843-6482

Goward, Trevor, Bruce McCune, and Del Meidinger. 1994. The Lichens of British Columbia. Illustrated Keys, Part 1-Foliose and Squalmulose Species. Special Report Series 8. Ministry of Forests Research Program. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. ISSN 0843-6482 Hale, Mason E. 1986. Arctoparmelia, A New Genus in the Parmeliaceae (Ascomycotina). Mycotaxon. January-March. Volume XXV, Number 1, pp. 251-254.

Hale, Mason E. 1986. Arctoparmelia, A New Genus in the Parmeliaceae (Ascomycotina). Mycotaxon. January-March. Volume XXV, Number 1, pp. 251-254. John, Elizabeth A. 1989. The Saxicolous Lichen Flora of Jonas Rockslide, Jasper National Park, Alberta

John, Elizabeth A. 1989. The Saxicolous Lichen Flora of Jonas Rockslide, Jasper National Park, Alberta McCune, B. and Geiser, L. 2023. Macrolichens of the Pacific Northwest. Third Edition, Revised and Expanded. Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon.

McCune, B. and Geiser, L. 2023. Macrolichens of the Pacific Northwest. Third Edition, Revised and Expanded. Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon. McCune, B., Rosentreter, R., Spribille, T., Breuss, O., and Wheeler, T. 2014. Montana Lichens: An Annotated List. Monographs in North American Lichenology, Volume 2, Northwest Lichenologists, Corvallis, Oregon.

McCune, B., Rosentreter, R., Spribille, T., Breuss, O., and Wheeler, T. 2014. Montana Lichens: An Annotated List. Monographs in North American Lichenology, Volume 2, Northwest Lichenologists, Corvallis, Oregon. Nash, TH, III (Ed.). 1996. Lichen Biology. Cambridge University Press, Great Britain. 303 pp.

Nash, TH, III (Ed.). 1996. Lichen Biology. Cambridge University Press, Great Britain. 303 pp. Wikipedia. 2025a. Mason E. Hale, Jr. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mason_Hale [Accessed 22 April 2025]

Wikipedia. 2025a. Mason E. Hale, Jr. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mason_Hale [Accessed 22 April 2025] Wikipedia. 2025b. Family Parmeliaceae. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parmeliaceae [Accessed 22 April 2025]

Wikipedia. 2025b. Family Parmeliaceae. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parmeliaceae [Accessed 22 April 2025]

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Concentric Ring Lichen"