View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Newell's Free-living Caddisfly - Rhyacophila newelli

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

This Rhyacophilan Caddisfly is currently ranked a "S2" Species of Concern in MT at risk because of very limited and/or potentially declining population numbers, range and/or habitat, making it vulnerable to extirpation in the state. Limited sites with small populations, but also difficult to identify without adult specimens.

General Description

Trichoptera is the largest order of insects that is entirely aquatic, with over 12,600 species worldwide (de Moor and Ivanov 2008). Caddisflies are most closely related to Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), and they share characteristics such as spinning silk. Rhyacophilids make up one of the largest genera of Trichoptera and are some of the most primitive caddisflies.

Caddisflies spend most of their life in the water as aquatic larvae and most species build portable, protective cases made from plant material or stones. Most caddisflies either filter small particles from the water by building nets spun from silk or shredded organic matter (e.g., leaves) into smaller pieces. The genus

Rhyacophila is a unique group because they do not build portable cases and are mainly predators. Not all

Rhyacophila have gills; those lacking gills absorb oxygen through their skin and thus require cold, oxygen-rich, fast-flowing water to breathe.

Caddisflies typically have five larval instars before pupation. Despite larvae being free-living,

Rhyacophila construct a shelter of small stones tied together with silk for pupation, and the pupa uses its mandibles to break through the case and emerge (Anderson 1976). Adults can live anywhere from a few days to several weeks.

Adult caddisflies are medium-sized insects with tent-shaped wings. They resemble moths, but caddisflies do not have a coiled proboscis and their wings are covered in hairs rather than scales. They tend to be secretive and slow-flying riparian insects (Anderson 1976).

Rhyacophila usually inhabit cool mountain streams and have small distributions, often restricted to only one or two mountain ranges (Anderson 1976).

Rhyacophila newelli is part of the Angelita group within

Rhyacophila. Only two species within this small group have been described:

R. angelita and

R. perplana (Giersch and Wisseman 2012). The larvae of the Angelita group are about 16mm long in their 5th and final instar and do not have gills. Their heads are parallel sided and yellow with variable dark patterns; later instars often have a dark band on the back of the head. When viewing the mandibles dorsally, they uniquely have just one apical tooth and a mesal tooth on the right mandible, and a single apical tooth on the left. The larvae of this group also have a unique apico-lateral spur on their anal proleg, but spurs can only clearly be seen in later instars. Giersch and Wisseman (2012) provide a key to identify larval

Rhyacophila.

Diagnostic Characteristics

See Denning 1971 for detailed adult description. Larval body length is 12-15 mm. Head usually wedge-shaped with patterning, no gills on the abdominal segments, apical extension off of the anal claw present. This species is a member of the angelita species group and cannot be separated as larvae from 2 other species that occur in Montana (see photo).

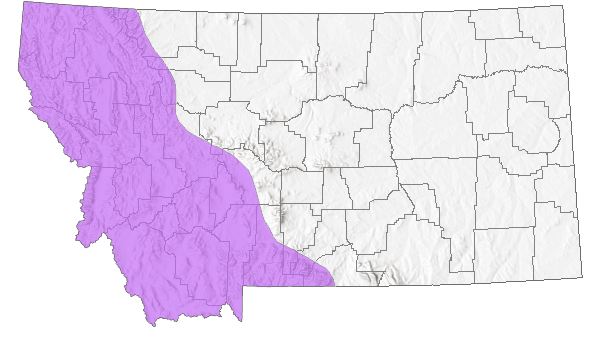

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

Rhyacophila newelli is known to occur in Montana, Alberta, and British Columbia. One adult male Rhyacophila newelli was collected in Rattlesnake Creek near Hungry Horse Reservoir in Missoula County, Montana in 1966 by R. A. Newell (Wold 1973). Because there are three species of the Angelita group found in Montana (including R. newelli) and no reliable larval key, dozens of reports of the Angelita group could contain this rare species (Stagliano et al. 2007); however, we cannot be sure without mature adults or DNA to verify it.

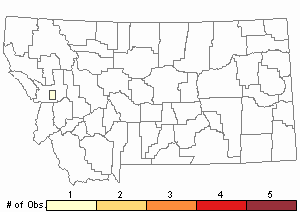

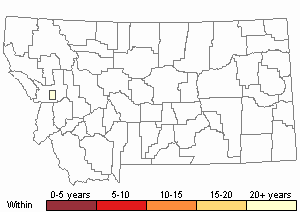

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 1

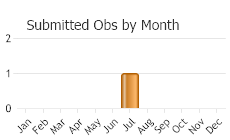

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Angelita group larvae are commonly collected in biomonitoring samples from streams in the montane west, ranging from small perennial channels to hard-bottomed rivers (Giersch and Wisseman 2012). This group is also found in a wide range of elevations and temperature regimes.

Rhyacophila newelli is associated with high gradient, perennially flowing headwater springs and streams (Stagliano et al. 2007).

Little is known about exactly what water temperatures this species inhabits; however, another

Rhyacophila species (

Rhyacophila vao) was recorded in a stream with an average annual water temperature of 3.7?. Additionally,

R. vao was found to not pupate until stream temperature exceeded 3? (Dixon and Wrona 1992).

More sensitive taxa (mayflies, caddisflies, and stoneflies) are usually found in areas with less deposited sediment, while the abundance of tolerant taxa (fingernail clams, scuds, and non-biting midges) increases with the percent of fine sediment in the stream (Waters 1995, Cole et al. 2003).

When timber harvest and forest regeneration is concerned, many studies have found that macroinvertebrate densities decrease as forest stand age increases; however, these young stands exhibit higher dominance by just a few taxa that are tolerant to disturbance due to increased solar radiation increasing primary production (Cole et al. 2003). Older stands show lower dominance of tolerant taxa likely because stream conditions are more stable, thus allowing the abundance of sensitive taxa like caddisflies to increase.

Food Habits

Larval Rhyacophilids are predaceous, but their feeding patterns change as they grow. Larvae in early instars tend to have a diet dominated by moss, diatoms, and detritus, but then eat more animal material after the third instar. Later instars of Rhyacophila mainly eat Chironomidae (non-biting midge) and other small fly larvae, Ephemeroptera (mayfly), Plecoptera (stonefly), other Trichopterans, Copepoda (crustacean), Acari (water mite), and even fish eggs (Thut 1969, Dudgeon and Richardson 1988). Rather than engulfing their prey whole, larval Rhyacophila only consume the soft parts of their prey, discarding tougher structures like legs and head capsules (Giersch 2002).

Little is known about the diet of adult Rhyacophila, but other adult caddisflies do not have developed mouthparts and only eat nectar or sap from plants during their short time as an adult.

Ecology

This species of Rhyacophila can be rather abundant in suitable habitat, but are usually fairly rare and very local in abundance (Stagliano et al. 2007).

Rhyacophila species are often sympatric, with several species occurring together at one site (Giersch 2002).

Reproductive Characteristics

The lifecycle of R. newelli has not been studied. Most caddisflies have a one-year life cycle, though some species reproduce more than once per year and others require two years to fully develop. Some species that are univoltine in lower elevation temperate streams may be semivoltine (more than one year) at higher latitudes or elevations where the growing season is too short for larvae to complete development in one year (Giersch 2002). After a short pupation phase, Rhyacophila transitions from the aquatic to the terrestrial environment. Prepupae and pupae may only be encountered in biomonitoring samples collected in the summer (Giersch and Wisseman 2012). Adult R. newelli have been collected in mid-July (Denning 1971), and likely emerge in late summer through autumn (Martin 1985, Hrovat and Urbanic 2012). The remainder of their lives are spent mating and reproducing. Adult caddisflies lay their eggs in or near water, either as strings surrounded by a cement-like matrix or as gelatinous masses (Anderson 1976). As adults, they use trees as roosting places.

Caddisfly adults tend to remain near the emergence site where oviposition occurs. Although dispersal flights are common, they are relatively short and only occur immediately following emergence. Dispersal from emergence sites tends to be negatively correlated with vegetation density (Collier and Smith 1998). In other words, caddisflies tend to disperse shorter distances in dense forest compared with more open areas.

Management

Limited data and the inability to identify larval collections has lead to a low global rank. Distribution data for United States and Canadian provinces is known to be incomplete or has not been reviewed for this taxon.

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

There is very limited information known about R. newelli, including distribution data and the inability to identify larvae (Stagliano et al. 2007). Specific threats to Montana populations of R. newelli include sediment and temperature increases resulting from road building, timber harvests, and other disturbances in forested riparian areas (Stagliano et al. 2007). In general, cold-water invertebrate specialists are sensitive to changes in aquatic habitat, such as alteration of flow patterns, streambed substrate, thermal characteristics, and water quality.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Anderson, N.H. 1976. The distribution and biology of the Oregon Trichoptera. Oregon Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 134:1-152.

Anderson, N.H. 1976. The distribution and biology of the Oregon Trichoptera. Oregon Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 134:1-152. Cole, M.B., K.R. Russell, and T.J. Mabee. 2003. Relation of headwater macroinvertebrate communities to in-stream and adjacent stand characteristics in managed second-growth forests of the Oregon Coast Range mountains. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 33:1433-1443.

Cole, M.B., K.R. Russell, and T.J. Mabee. 2003. Relation of headwater macroinvertebrate communities to in-stream and adjacent stand characteristics in managed second-growth forests of the Oregon Coast Range mountains. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 33:1433-1443. Collier, K.J. and B.J. Smith. 1998. Dispersal of adult caddisflies (Trichoptera) into forests alongside three New Zealand streams. Hydrobiologia, 361: 53-65.

Collier, K.J. and B.J. Smith. 1998. Dispersal of adult caddisflies (Trichoptera) into forests alongside three New Zealand streams. Hydrobiologia, 361: 53-65. de Moor, F.C. and V.C. Ivanov. 2008. Global diversity of caddisflies (Trichoptera: Insecta) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 595:393-407.

de Moor, F.C. and V.C. Ivanov. 2008. Global diversity of caddisflies (Trichoptera: Insecta) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 595:393-407. Denning, D. G. 1971. A new genus and new species of Trichoptera. Pan-Pacific Entomol. 47:203-210.

Denning, D. G. 1971. A new genus and new species of Trichoptera. Pan-Pacific Entomol. 47:203-210. Dixon, R.W.J. and F.J. Wrona. 1992. Life history and production of the predatory caddisfly Rhyacophila vao Milne in a spring-fed stream. Freshwater Biology 27:1-11.

Dixon, R.W.J. and F.J. Wrona. 1992. Life history and production of the predatory caddisfly Rhyacophila vao Milne in a spring-fed stream. Freshwater Biology 27:1-11. Dudgeon, D. And J.S. Richardson. 1988. Dietary variations of predaceous caddisfly larvae (Trichoptera: Rhyacophilidae, Polycentropodidae and Arctopsychidae) from British Columbian streams. Hydrobiologia 160(1):33-43.

Dudgeon, D. And J.S. Richardson. 1988. Dietary variations of predaceous caddisfly larvae (Trichoptera: Rhyacophilidae, Polycentropodidae and Arctopsychidae) from British Columbian streams. Hydrobiologia 160(1):33-43. Giersch, J. and R. Wisseman. 2012. Annotated list of Rhyacophila of North America with larval key and descriptions. U.S. Geological Survey, Southwest Assoc. of Freshwater Invertebrate Taxonomists Workshop 2012. 133 p.

Giersch, J. and R. Wisseman. 2012. Annotated list of Rhyacophila of North America with larval key and descriptions. U.S. Geological Survey, Southwest Assoc. of Freshwater Invertebrate Taxonomists Workshop 2012. 133 p. Giersch, J. J. 2002. Revision and phylogenetic analysis of the verrula and alberta species group of Rhyacophila pictet 1834 with description of a new species (Trichoptera: Rhyacophilidae). Master's of Science Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman, MT. 206 pp.

Giersch, J. J. 2002. Revision and phylogenetic analysis of the verrula and alberta species group of Rhyacophila pictet 1834 with description of a new species (Trichoptera: Rhyacophilidae). Master's of Science Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman, MT. 206 pp. Hrovat, M. and G. Urbanic. 2012. Life cycle of Rhyacophila fasciata Hagen, 1859 and Hydropsyche saxonica McLachlan, 1884 in a Dinaric karst river system. Aquatic Insects 34(1):113-125.

Hrovat, M. and G. Urbanic. 2012. Life cycle of Rhyacophila fasciata Hagen, 1859 and Hydropsyche saxonica McLachlan, 1884 in a Dinaric karst river system. Aquatic Insects 34(1):113-125. Martin, I.D. 1985. Microhabitat selection and life cycle patterns of two Rhyacophila species (Trichoptera: Rhyacophilidae) in southern Ontario streams. Freshwater Biology 15:1-14.

Martin, I.D. 1985. Microhabitat selection and life cycle patterns of two Rhyacophila species (Trichoptera: Rhyacophilidae) in southern Ontario streams. Freshwater Biology 15:1-14. Stagliano, D.M., G.M. Stephens, and W.R. Bosworth. 2007. Aquatic invertebrate species of concern on USFS northern region lands. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana and Idaho Conservation Data Center, Boise, Idaho. 153 p.

Stagliano, D.M., G.M. Stephens, and W.R. Bosworth. 2007. Aquatic invertebrate species of concern on USFS northern region lands. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana and Idaho Conservation Data Center, Boise, Idaho. 153 p. Thut, R.N. 1969. Feeding habits of larvae of seven Rhyacophila (Trichoptera:Rhyacophilidae) species with notes on other life-history features. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 62(4):894-898.

Thut, R.N. 1969. Feeding habits of larvae of seven Rhyacophila (Trichoptera:Rhyacophilidae) species with notes on other life-history features. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 62(4):894-898. Waters, T.F. 1995. Sediment in streams: Sources, biological effects, and control. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland. Monograph 7.

Waters, T.F. 1995. Sediment in streams: Sources, biological effects, and control. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland. Monograph 7. Wold, J.L. 1973. Systematics of the genus Rhyacophila (Trichoptera; Rhyacophilidae) in western North America with special reference to the immature stages. M.Sc. Thesis. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University. 229 p.

Wold, J.L. 1973. Systematics of the genus Rhyacophila (Trichoptera; Rhyacophilidae) in western North America with special reference to the immature stages. M.Sc. Thesis. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University. 229 p.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Merritt, R.W. and K.W. Cummins. 1996. An introduction to the aquatic insects of North America. 3rd Edition. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. Dubuque, Iowa. 862 pp.

Merritt, R.W. and K.W. Cummins. 1996. An introduction to the aquatic insects of North America. 3rd Edition. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. Dubuque, Iowa. 862 pp. Newell, R.L. and D.S. Potter. 1973. Distribution of some Montana caddisflies. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 33:12-21.

Newell, R.L. and D.S. Potter. 1973. Distribution of some Montana caddisflies. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 33:12-21. Wiggins, G.B. 1996. Larvae of the North American caddisfly genera (Trichoptera). University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Ontario. 2nd Edition. 457 p.

Wiggins, G.B. 1996. Larvae of the North American caddisfly genera (Trichoptera). University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Ontario. 2nd Edition. 457 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Newell's Free-living Caddisfly"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Insects"