View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Great Grig - Cyphoderris monstrosa

Other Names:

Great Hump-winged Cricket

General Description

The following is taken from Hebard (1928), Helfer (1971), Morris and Gwynne (1978), Vickery and Kevan (1985), Capinera et al. (2004), and Scott (2010). The genus

Cyphoderris is represented by two species in Montana, the Great Grig (

C. monstrosa) and the

Buckell’s Grig (

C. buckelli). They are short-winged (tegmina) and flightless. The female wings are reduced to small oval lobes, and male wings are well developed for loud stridulation (“singing”). The Hump-wing Grigs are small to medium sized, robust, and bear similar body colors with contrasting black markings.

As in Crickets, the

Grylloidae, stridulation is performed only by males and is generated by scraping one wing over the other. Unlike male crickets, which generally have the right wing with a scraper overlapping the top of the left wing with a file, the Grig’s wings are mirror images with both wings bearing a functional file and scraper. Thus,

Cyphoderris males are able to change their wing overlap positions where both wing files are used in its singing, which produces a variation in their song’s intensity and frequency. This suggests that such changes are the result of irregular switching of the wings from top to bottom positions, a habit referred to as “switch-wing singing,” and occurs several times in the course of a single trill. In the field, the night songs of both

Cyphoderris species are almost indistinguishable. The song of

C. monstrosa has been described as “a loud, penetrating, high-pitched, shrill, metallic trill repeated at rates of 15 to 20 per minute (Spooner 1973). However, song rates are subject to rising and declining due to ambient temperature or courtship calling. Grig species are known for their singing activity at much lower temperatures than that of other

Ensifera species (suborder of katydids and crickets). For more detail and acoustical sonograms of these behaviorally complex species, refer to the papers by Fulton (1930), Spooner (1973), Morris and Gwynne (1978), Morris et al. (2002).

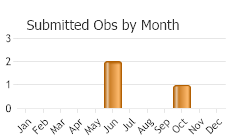

Phenology

All Cyphoderris species are believed to overwinter concealed as a nymph, emerging in late spring to early summer when they become an adult in June, and remain active to November or the onset of cold weather (Morris and Gwynne 1978, Vickery and Kevan 1985, and Scott 2010).

Diagnostic Characteristics

The following comes from Hebard (1928), Helfer (1971), Morris and Gwynne (1978), Vickery and Kevan (1985), Capinera et al. (2004), and Scott (2010). The body length for males and females of this species is 20 mm to 30 mm (

C. monstrosa) tends to be larger than its congener,

C. buckelli. Both sexes possess the Ander’s organ, a reddish ridged patch on the dorsolateral side of the first abdominal segment (see illustration). The male genitalia has a prominent ventrally-directed sternal process shaped like the claw of a hammer on the 9th abdominal segment (see illustration lateral view).

The two species of

Cyphoderris occurring in Montana are easily confused at first glance. There is also a third North American Grig species, the Sagebrush Grig (

C. strepitans), which occurs only along the Rocky Mountain front of Wyoming and Colorado. Grigs can also be confused with the Decticids—the Shield-backed Katydids (Helfer 1971, Morris and Gwynne 1978, Vickery and Kevan 1985, and Scott 2010).

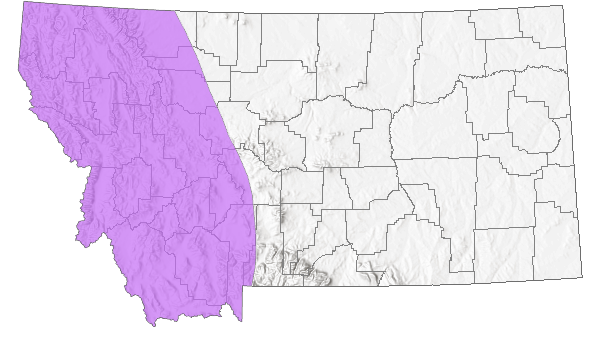

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

A northwest mountain species occurring from British Columbia, southward through Washington, Oregon, Idaho, western Montana, to northern California. It has been reported in four Montana counties (Vickery and Kevan 1985, and Scott 2010).

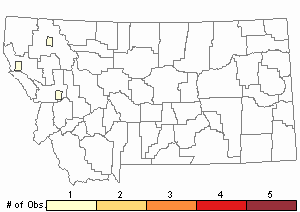

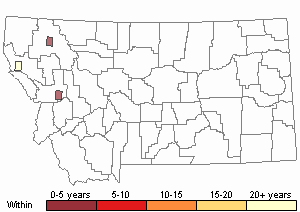

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 23

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Specimens have been found under stones and in buildings. Prefers coniferous forest areas containing

Lodgepole pine (

Pinus contorta),

Engelmann spruce (

Picea englemannii), and

Mountain Hemlock (

Tsuga mertensiana). The Great Grig is the only species in this genus that climbs trees to about 18 feet. Field observations indicate they usually occur in groups of 2 to 4 individuals on the same tree trunk with their heads pointed upward (Morris and Gwynne 1978, Vickery and Kevan 1985, and Scott 2010).

Food Habits

Great Grig (

C. monstrosa) adults and nymphs have been found to feed on the staminate cones of

Lodgepole pine (

Pinus contorta) (this is before the cones reach the “loose pollen” stage). This causes this Grig species to climb high in the conifers (Morris and Gwynne 1978, Vickery and Kevan 1985, and Scott 2010).

Reproductive Characteristics

The following is taken from Morris and Gwynne (1978), Vickery and Kevan (1985), and Morris et al. (1989). When a receptive female arrives at a singing male, she mounts him so that her mouth parts are above his short forewings (the tegmina). The male ceases singing, lifts and separates the tegmina, exposing his smaller hindwings. If the female does not move away, she begins to consume her mate’s hindwings, releasing the flow of hemolymph (equivalent to blood in other organisms). While the female feeds, the male extends his telescoping abdomen with its dorso-posterior pinching organ (called the “gin trap”) and attempts to grasp and draw the female’s genitalia into contact with his genitalia. Upon making successful contact, the female continues to feed on the wings, the male’s abdomen pumps up and down releasing and transferring a spermatophore with a spermatophylax, which the female consumes after mating. The nutrients contained in the wings and spermatophylax (the “nuptial gifts”) enables the female to produce her eggs. Both male and female are ready to mate again, but the male has a problem. He may no longer possess enough nutritious hind wing material left from the first mating to attract and feed a second mate because the hind wings do not grow back. Thus, females generally prefer to mate with virgin males.

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Capinera, J.L., R.D. Scott, and T.J. Walker. 2004. Field Guide to Grasshoppers, Katydids, and Crickets of the United States. Ithaca, NY. Cornell University Press.

Capinera, J.L., R.D. Scott, and T.J. Walker. 2004. Field Guide to Grasshoppers, Katydids, and Crickets of the United States. Ithaca, NY. Cornell University Press. Fulton, B.B. 1930. Notes on Oregon Orthoptera with descriptions of new species and races. Annals of the Entomological Society of America XXIII(4).

Fulton, B.B. 1930. Notes on Oregon Orthoptera with descriptions of new species and races. Annals of the Entomological Society of America XXIII(4). Hebard, M. 1928. The Orthoptera of Montana. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Vol. 80:211-306.

Hebard, M. 1928. The Orthoptera of Montana. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Vol. 80:211-306. Helfer, J.R. 1971. How to Know the Grasshoppers, Crickets, Cockroaches, and Their Allies. Revised edition (out of print), Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

Helfer, J.R. 1971. How to Know the Grasshoppers, Crickets, Cockroaches, and Their Allies. Revised edition (out of print), Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. Morris, G.K. and D.T. Gwynne. 1978. Geographical distribution and biological observations of Cyphoderris (Orthoptera: Haglidae) with a description of a new species. PSYCHE 85:2-3.

Morris, G.K. and D.T. Gwynne. 1978. Geographical distribution and biological observations of Cyphoderris (Orthoptera: Haglidae) with a description of a new species. PSYCHE 85:2-3. Morris, G.K., D.T. Gwynne, D.E. Klimas, and S.K. Sakaluk. 1989. Virgin male mating advantage in a primitive acoustic insect (Orthoptera: Haglidae). Journal of Insect Behavior 2(2).

Morris, G.K., D.T. Gwynne, D.E. Klimas, and S.K. Sakaluk. 1989. Virgin male mating advantage in a primitive acoustic insect (Orthoptera: Haglidae). Journal of Insect Behavior 2(2). Morris, G.K., P.A. DeLuca, M. Norton, and A.C. Mason. 2002. Calling-song function in male haglids (Orthoptera: Haglidae, Cyphoderris). Canadian Journal of Zoology 80:271-285.

Morris, G.K., P.A. DeLuca, M. Norton, and A.C. Mason. 2002. Calling-song function in male haglids (Orthoptera: Haglidae, Cyphoderris). Canadian Journal of Zoology 80:271-285. Scott, R.D. 2010. Montana Grasshoppers, Katydids, and Crickets A Pictorial Field Guide to the Orthoptera. MagpieMTGraphics, Billings, MT.

Scott, R.D. 2010. Montana Grasshoppers, Katydids, and Crickets A Pictorial Field Guide to the Orthoptera. MagpieMTGraphics, Billings, MT. Spooner, J.D. 1973. Sound production in Cyphoderris monstrosa (Orthoptera: Prophalangopsidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 66:4-5.

Spooner, J.D. 1973. Sound production in Cyphoderris monstrosa (Orthoptera: Prophalangopsidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 66:4-5. Vickery, V. R. and D. K. M. Kevan. 1985. The grasshopper, crickets, and related insects of Canada and adjacent regions. Biosystematics Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario. Publication Number 1777. 918 pp.

Vickery, V. R. and D. K. M. Kevan. 1985. The grasshopper, crickets, and related insects of Canada and adjacent regions. Biosystematics Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario. Publication Number 1777. 918 pp.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Chivers, B.D., O. Bethoux, F.A. Sarria, T. Jonsson, A.C. Mason, and F. Montealegre. 2017. Functional morphology of tegmina-based stridulation in the relict species Cyphoderris monstrosa (Orthoptera: Ensifera: Prophalangopsidae). The Company of Biologists Ltd. Journal of Experimental Biology 220:1112-1121.

Chivers, B.D., O. Bethoux, F.A. Sarria, T. Jonsson, A.C. Mason, and F. Montealegre. 2017. Functional morphology of tegmina-based stridulation in the relict species Cyphoderris monstrosa (Orthoptera: Ensifera: Prophalangopsidae). The Company of Biologists Ltd. Journal of Experimental Biology 220:1112-1121. Dodson, G.N., G.K. Morris, and D.T. Gwynne. 1983. Mating Behavior of the Primitive Orthopteran Genus Cyphoderris (Haglidae). In: D.T. Gwynne and G.K. Morris (eds). Orthopteran Mating Systems. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Dodson, G.N., G.K. Morris, and D.T. Gwynne. 1983. Mating Behavior of the Primitive Orthopteran Genus Cyphoderris (Haglidae). In: D.T. Gwynne and G.K. Morris (eds). Orthopteran Mating Systems. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Gwynne, D.T. 2001. Katydids and Bush-Crickets, Reproductive Behavior and Evolution of the Tettigoniidae. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Gwynne, D.T. 2001. Katydids and Bush-Crickets, Reproductive Behavior and Evolution of the Tettigoniidae. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Hebard, M. 1934. Cyphoderris, a genus of katydid of southwestern Canada and the northwestern United States. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 59:371-375.

Hebard, M. 1934. Cyphoderris, a genus of katydid of southwestern Canada and the northwestern United States. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 59:371-375. Kumala, M., D.A. McLennan, D.R. Brooks, and A.C. Mason. 2005. Phylogenetic relationships within hump-winged grigs, Cyphoderris (Insecta, Orthoptera, Tettigonioidea, Haglidae). Canadian Journal of Zoology 83:1033-1011

Kumala, M., D.A. McLennan, D.R. Brooks, and A.C. Mason. 2005. Phylogenetic relationships within hump-winged grigs, Cyphoderris (Insecta, Orthoptera, Tettigonioidea, Haglidae). Canadian Journal of Zoology 83:1033-1011

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Great Grig"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Insects"