View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Western Tiger Beetle - Cicindela oregona

General Description

The following is taken from Wallis (1961), Kippenhan (1994), Acorn (2001), and Pearson et al. (2015). This species is highly variable across its range, maculations are wider in the south, and body size is greater in the north. Body length is 11-14 mm. Subspecies in Montana are mostly dark brown to rich-brown above, but some individuals are green. Maculations complete, thin to moderate, often reduced to dots instead of crescents or lines, marginal line absent on middle of elytra, middle band with abrupt bend to rear forming an “elbow.” Below, metallic coppery, purple or blue. Forehead with only a few hairs (setae) above eyes, a small cluster near the inner front edge of the eyes; first antennomere with 3 sensory setae and 5 or fewer accessory setae, labrum short with 1 tooth.

Phenology

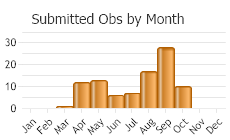

Tiger beetle life cycles fit two general categories based on adult activity periods. “Spring-fall” beetles emerge as adults in late summer and fall, then overwinter in burrows before emerging again in spring when mature and ready to mate and lay eggs. The life cycle may take 1-4 years. “Summer” beetles emerge as adults in early summer, then mate and lay eggs before dying. The life cycle may take 1-2 years, possibly longer depending on latitude and elevation (Kippenhan 1994, Knisley and Schultz 1997, Leonard and Bell 1999, and Pearson et al. 2015). Adult Cicindela oregona is a spring-fall species, found mid-February to early November but mostly May-June and August-September, and mostly April-June and August-early October in northern parts of range (Larochelle and Larivière 2001); late March to mid-September in Nevada (Sumlin 1976), early June to late September in northern California (Smith and Bronson 2003), May to August in south-central Washington (Looney et al. 2014). In Montana, early April to mid-October (Nate Kohler personal communication, iNaturalist 2024).

Diagnostic Characteristics

The following comes largely from Wallis (1961), Kippenhan (1994), Acorn (2001) and Pearson et al. (2015). Most similar in appearance to the

Twelve-spotted Tiger Beetle (

Cicindela duodecimguttata) where the species overlap along the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains;

Cicindela duodecimguttata usually has a distinct or remnant short white marginal line along middle of the outer edge of the elytra, lacking in

C. oregona, and the forehead of

C. oregona is mostly hairless, not hairy as with

Cicindela duodecimguttata.

Dispirited Tiger Beetle (

C. depressula) has a middle band (maculation) with a shallow, wave-like bend to the rear with no sharp turn, whereas

C. oregona has a sharp bend rearward, forming a distinct “elbow.”

Bronze Tiger Beetle (

C. repanda) has a distinct, if incomplete, marginal band on the outer edge of the elytra that is lacking in

C. oregona, and the forehead is hairy, not mostly hairless.

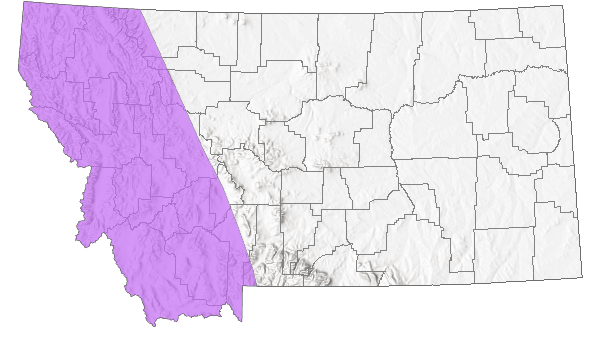

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

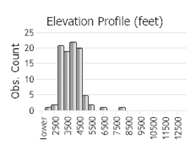

Cicindela oregona occurs widely in western North America, from Alaska south into western Mexico, and east to the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains from Alberta to New Mexico. Documented in all Idaho counties adjacent to Montana except those bordering Beaverhead County, with the exception of Fremont County to the south (Shook 1984, Idaho Fish and Game, https://idfg.idaho.gov/species/taxa; accessed 31 January 2024). In Montana, reported from at least 19 counties between the Idaho border and Cascade County in the north, Yellowstone County in the south; to at least 8179 ft (2493 m) elevation, in Beaverhead County (Nate Kohler personal communication, iNaturalist 2024).

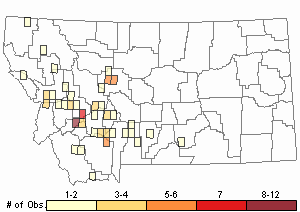

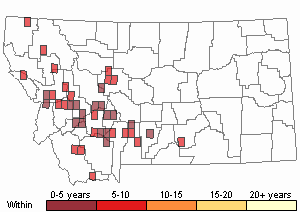

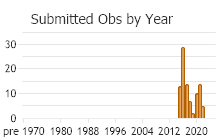

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 137

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

Non-migratory but capable of dispersal. When wings fully developed (macropterous), generally a strong flier (except

C. oregona oregona), fast runner (Larochelle and Larivière 2001).

Habitat

Adult and larval tiger beetle habitat is essentially identical, the larvae live in soil burrows (Knisley and Schultz 1997). Cicindela oregona is found close to water on sparsely vegetated soils of various fluvial habitats, mudflats, alkali lake shores, salt marshes, livestock reservoirs, edges of ponds, freshwater lakes, drainage channels at hot springs and fumeroles, sand and gravel banks of rivers, streams and creeks, sand bars, dunes, other river sand deposits, coastal trails, beaches, and tidal flats (Vaurie 1950, Wallis 1961, Knisley 1984, Kippenhan 1994, Acorn 2001, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Smith and Bronson 2003, Rogers and Rogers 2004, Cornelisse and Hafernik 2009, Pearson et al. 2015, Looney et al. 2014, Sauder 2017). In Montana, habitat is similar to elsewhere inland, including dunes and two-tracks near rivers, sand bars and riverbanks, along streams, shores of freshwater lakes and reservoirs, reclamation pond edges, and fishing access sites (Nate Kohler personal communication, iNaturalist 2024).

Food Habits

Larval and adult tiger beetles are predaceous. In general, both feed considerably on ants (Wallis 1961, and Knisley and Schultz 1997). Adult foods of Cicindela oregona in the field include various small arthropods, adult damselflies and midge (chironomid) larvae (30-31% success rate on the latter), also scavenge dead and dying beetles (dytiscids), dipterans, lepidopterans and odonates around fumaroles and near hot springs; foods in captivity include small crickets and house flies. Larval foods in the field include ants, damselflies, tabanid flies, and beetles (coccinelids); larvae can be cannibalistic when coming into contact (Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Kippenhan 2002, Rogers and Rogers 2004, and Lyons 2015).

Ecology

Larval tiger beetles live in burrows and molt through three instars to pupation, which also occurs in the larval burrow. Adults make shallow burrows in soil for overnight protection, deeper burrows for overwintering. Adults are sensitive to heat and light and are most active during sunny conditions. Excessive heat during midday on sunny days drives adults to seek shelter among vegetation or in burrows (Wallis 1961, Knisley and Schultz 1997, and Pearson et al. 2015). The subspecies of

Cicindela oregona occurring in Montana have wide ranges (eurytopic) of ecological tolerance. Adults are diurnal and gregarious, becoming active at about 15°C and remaining so at 25-38°C. Escapes by slow flights of up to 3 m or burrows into shallow sand when pursued, quite wary, releases defensive secretions when captured (Schultz and Hadley 1987, and Larochelle and Larivière 2001). Predators of adults include frogs and gnaphosid spiders, probably birds and robber flies (asilids); larvae parasitized by bee flies (bombyliids) and probably tiphiid wasps. Associated tiger beetle species include

C. columbica,

C. duodecimguttata,

C. (=Cicindelidia) hemorrhagica,

C. hirticollis,

C. repanda, and

C. tranquebarica (Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Smith and Bronson 2003, Pearson et al. 2015, and Sauder 2017).

Reproductive Characteristics

Life cycle of

Cicindela oregona is 2 years. Mate in May and July; females oviposit in May and July. Larval burrows usually clustered, 12-30 cm deep and 1.5-3.0 mm diameter (depending on instar), and vertical if on flats, horizontal if in banks, excavated in open and moist loose sand near water. Overwinter as third-instar larvae, reemerge in spring then pupate in early summer, sexually immature adults (fresh tenerals) emerge in August and September then overwinter before reemerging the following spring to mate. Interspecific copulation observed with

C. repanda, and

C. willistoni (Vaurie 1950, Acorn 2001, Larochelle and Larivière 2001, Cornelisse and Hafernik 2009, Lyons 2015, and Pearson et al. 2015). Mating observed in Montana in late May and late July (iNaturalist 2024), otherwise no information.

Management

Not considered rare or in need of special conservation management (Knisley et al. 2014). Cicindela oregona may be sensitive to altered river and stream flows through damming and channelization, which alters sediment deposition. Flash flooding (in the desert southwest) forces adults to disperse and colonize newly-created habitat where sand is deposited (Pearson et al. 2015). Early-succession habitats near water favored by this species experience vegetation encroachment as succession proceeds for whatever reason (Shelford 1907, and Knisley 1979), and benefit from disturbance that retains a mosaic of successional conditions. Some colonies (particularly larval burrows) could be impacted by trampling from human foot traffic and livestock overgrazing or access to water sources at lakes, streams and rivers (Cornelisse and Hafernik 2009, Knisley 2011). Grazing at appropriate times and stocking levels, however, could be beneficial by keeping vegetation cover more open. Retention and restoration of natural stream and river sediment-deposition processes (especially of sand) will also benefit this species.

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Acorn, J. 2001. Tiger beetles of Alberta: killers on the clay, stalkers on the sand. The University of Alberta Press, Edmonton, Alberta. 120 p.

Acorn, J. 2001. Tiger beetles of Alberta: killers on the clay, stalkers on the sand. The University of Alberta Press, Edmonton, Alberta. 120 p. Cornelisse, T.M. and J.E. Hafernik. 2009. Effects of soil characteristics and human disturbance on tiger beetle oviposition. Ecological Entomology 34:495-503.

Cornelisse, T.M. and J.E. Hafernik. 2009. Effects of soil characteristics and human disturbance on tiger beetle oviposition. Ecological Entomology 34:495-503. Idaho Fish and Game. Explore Idaho's Plants and Animals. Accessed 31 January 2024. https://idfg.idaho.gov/species/taxa

Idaho Fish and Game. Explore Idaho's Plants and Animals. Accessed 31 January 2024. https://idfg.idaho.gov/species/taxa iNaturalist. Research-grade Observations. Accessed 24 January 2024. https://www.inaturalist.org/

iNaturalist. Research-grade Observations. Accessed 24 January 2024. https://www.inaturalist.org/ Kippenhan, M.G. 2002. Observation of Cicindela oregona scavenging on dead arthropod. Cicindela 34(1-2):8.

Kippenhan, M.G. 2002. Observation of Cicindela oregona scavenging on dead arthropod. Cicindela 34(1-2):8. Kippenhan, Michael G. 1994. The Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Colorado. 1994. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 120(1):1-86.

Kippenhan, Michael G. 1994. The Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Colorado. 1994. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 120(1):1-86. Knisley, C.B. 1979. Distribution, abundance, and seasonality of tiger beetles (Cicindelidae) in the Indiana Dunes region. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 88:209-217.

Knisley, C.B. 1979. Distribution, abundance, and seasonality of tiger beetles (Cicindelidae) in the Indiana Dunes region. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 88:209-217. Knisley, C.B. 1984. Ecological distribution of tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) in Colfax County, New Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist 29(1):93-104.

Knisley, C.B. 1984. Ecological distribution of tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) in Colfax County, New Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist 29(1):93-104. Knisley, C.B. 2011. Anthropogenic disturbances and rare tiger beetle habitats: benefits, risks, and implications for conservation. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 4:41-61.

Knisley, C.B. 2011. Anthropogenic disturbances and rare tiger beetle habitats: benefits, risks, and implications for conservation. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 4:41-61. Knisley, C.B., and T.D. Schultz. 1997. The biology of tiger beetles and a guide to the species of the south Atlantic states. Virginia Museum of Natural History Special Publication Number 5. 210 p.

Knisley, C.B., and T.D. Schultz. 1997. The biology of tiger beetles and a guide to the species of the south Atlantic states. Virginia Museum of Natural History Special Publication Number 5. 210 p. Knisley, C.B., M. Kippenhan, and D. Brzoska. 2014. Conservation status of United States tiger beetles. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 7:93-145.

Knisley, C.B., M. Kippenhan, and D. Brzoska. 2014. Conservation status of United States tiger beetles. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 7:93-145. Kohler, Nathan S. Excel spreadsheets of tiger beetle observations. 6 August 2022.

Kohler, Nathan S. Excel spreadsheets of tiger beetle observations. 6 August 2022. Larochelle, A and M Lariviere. 2001. Natural history of the tiger beetles of North America north of Mexico. Cicindela. 33:41-162.

Larochelle, A and M Lariviere. 2001. Natural history of the tiger beetles of North America north of Mexico. Cicindela. 33:41-162. Leonard, Jonathan G. and Ross T. Bell, 1999. Northeastern Tiger Beetles: a field guide to tiger beetles of New England and eastern Canada. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 176 p.

Leonard, Jonathan G. and Ross T. Bell, 1999. Northeastern Tiger Beetles: a field guide to tiger beetles of New England and eastern Canada. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 176 p. Looney, C., R.S. Zack, J.R. LaBonte. 2014. Ground beetles (Coleoptera, Carabidae) of the Hanford Nuclear Site in south-central Washington State. ZooKeys 396:13-42.

Looney, C., R.S. Zack, J.R. LaBonte. 2014. Ground beetles (Coleoptera, Carabidae) of the Hanford Nuclear Site in south-central Washington State. ZooKeys 396:13-42. Lyons, R. 2015. The end of one - a meal for another. Argia 27(3):30-32.

Lyons, R. 2015. The end of one - a meal for another. Argia 27(3):30-32. Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, D.P. Duran, and C.J. Kazilek. 2015. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada, second edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 251 p.

Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, D.P. Duran, and C.J. Kazilek. 2015. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada, second edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 251 p. Rogers, D.C. and E.C.L. Rogers. 2004. Observations on feeding behavior in western North American tiger beetles. Cicindela 36(1-2):17-21.

Rogers, D.C. and E.C.L. Rogers. 2004. Observations on feeding behavior in western North American tiger beetles. Cicindela 36(1-2):17-21. Sauder, J.D. 2017. Status update of Cicindela columbica (Hatch) (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicndelinae) in Idaho. The Coleopterists Bulletin 71(3):631-634.

Sauder, J.D. 2017. Status update of Cicindela columbica (Hatch) (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicndelinae) in Idaho. The Coleopterists Bulletin 71(3):631-634. Schultz, T.D. and N.F. Hadley. 1987. Microhabitat segregation and physiological differences in co-occurring tiger beetle species, Cicindela oregona and Cicindela tranquebarica. Oecologia 73:363-370.

Schultz, T.D. and N.F. Hadley. 1987. Microhabitat segregation and physiological differences in co-occurring tiger beetle species, Cicindela oregona and Cicindela tranquebarica. Oecologia 73:363-370. Shook, G.A. 1984. Checklist of tiger beetles from Idaho (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Great Basin Naturalist 44(1):159-160.

Shook, G.A. 1984. Checklist of tiger beetles from Idaho (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Great Basin Naturalist 44(1):159-160. Smith, C.R. and L.R. Bronson. 2003. Distribution, habitat preferences and seasonality of tiger beetles, genus Cicindela (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae), in Surprise Valley, Modoc County, California. Cicindela 35(1-2):1-22.

Smith, C.R. and L.R. Bronson. 2003. Distribution, habitat preferences and seasonality of tiger beetles, genus Cicindela (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae), in Surprise Valley, Modoc County, California. Cicindela 35(1-2):1-22. Sumlin, W.D. III. 1976. Notes on the tiger beetle holdings of the Nevada state Department of Agriculture (Coleoptera: Cicndelidae). The Coleopterists Bulletin 30(1):101-106.

Sumlin, W.D. III. 1976. Notes on the tiger beetle holdings of the Nevada state Department of Agriculture (Coleoptera: Cicndelidae). The Coleopterists Bulletin 30(1):101-106. Vaurie, P. 1950. Notes on the habitats of some North American tiger beetles. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 58(3):143-153.

Vaurie, P. 1950. Notes on the habitats of some North American tiger beetles. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 58(3):143-153. Wallis, J.B. 1961. The Cicindelidae of Canada. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press. 74 p.

Wallis, J.B. 1961. The Cicindelidae of Canada. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press. 74 p.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Bousquet, Yves. 2012. Catalogue of Geadephaga (Coleoptera; Adephaga) of America north of Mexico. ZooKeys. 245:1-1722.

Bousquet, Yves. 2012. Catalogue of Geadephaga (Coleoptera; Adephaga) of America north of Mexico. ZooKeys. 245:1-1722. Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, and C.J. Kazilek. 2006. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada: identification, natural history, and distribution of the Cicindelidae. Oxford University Press, New York, New York. 227 pp.

Pearson, D.L., C.B. Knisley, and C.J. Kazilek. 2006. A field guide to the tiger beetles of the United States and Canada: identification, natural history, and distribution of the Cicindelidae. Oxford University Press, New York, New York. 227 pp. Sater, S. 2022. The insects of Sevenmile Creek, a pictorial guide to their diversity and ecology. Undergraduate Thesis. Helena, MT: Carroll College. 242 p.

Sater, S. 2022. The insects of Sevenmile Creek, a pictorial guide to their diversity and ecology. Undergraduate Thesis. Helena, MT: Carroll College. 242 p. Shelford, V.E. 1907. Preliminary note on the distribution of the tiger beetles (Cicindela) and its relation to plant succession. Biological Bulletin 14:9-14.

Shelford, V.E. 1907. Preliminary note on the distribution of the tiger beetles (Cicindela) and its relation to plant succession. Biological Bulletin 14:9-14. Sikes, D.S. 1994. Influences of ungulate carcasses on Coleopteran communities in Yellowstone National Park, USA. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 179 p.

Sikes, D.S. 1994. Influences of ungulate carcasses on Coleopteran communities in Yellowstone National Park, USA. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 179 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Western Tiger Beetle"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Insects"