View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Sicklefin Chub - Macrhybopsis meeki

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is uncommon but faces low level threats and is stable to declining

General Description

The Sicklefin Chub is a rare, large-river minnow species found in the lower Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers (Large Valley River Ecosystems) of Montana. It was first collected in 1979, and to date has only been found in about a dozen river segments. Because it is rare and specialized to this large river system, it is a Montana Fish of Special Concern. Its general habitat and distribution is much like that of the Sturgeon Chub. The Sicklefin Chub is found in large, turbid streams in the plains region of Montana. This species is very similar in appearance to the Sturgeon Chub except that its pectoral fins are strikingly long. The life history features and maximum size of the Sicklefin Chub are similar to those of the Sturgeon Chub.

For a comprehensive review of the ecology, conservation status, threats, and management of this and other Montana fish species of concern, please see

Montana Chapter of the American Fisheries Society Species of Concern Status Reviews.Diagnostic Characteristics

Sicklefin Chub are light brown on the back and upper sides and silvery-white below. There is a conspicuous barbel at each corner of the mouth.

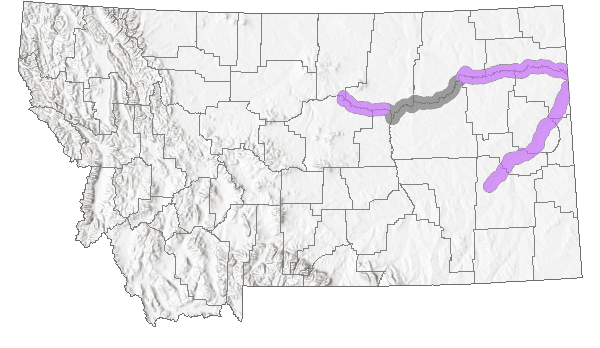

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Western Hemisphere Range

Western Hemisphere Range

Range Comments

The sicklefin chub is native to the Missouri-Mississippi river basins from Montana to Louisiana; they were first collected from the Missouri River in Montana in 1979. The historic distribution included approximately 3,379 km of the main stem Missouri River and ~1,850 km of the Mississippi River, plus the Yellowstone River in Montana. Current distribution includes about 1,858 km (55%) of their historical range in the Missouri River because of dams and loss of habitat.

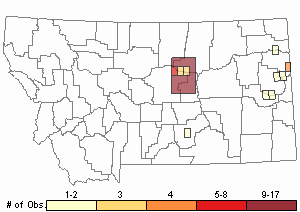

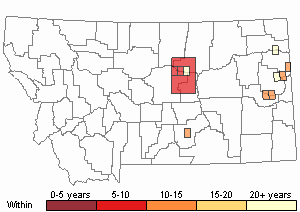

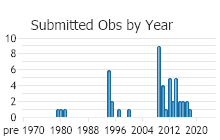

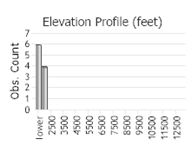

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 47

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

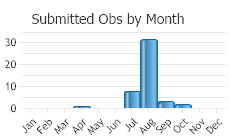

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Sicklefin Chub are strictly confined to the main channels of large, turbid rivers where they live in a strong current over a bottom of sand or fine gravel (Pflieger 1975).

Unlike the Sturgeon Chub, all of the Montana captures have been from only the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers, indicating a strong preference for large turbid rivers (

Montana AFS Species Status Account).

Food Habits

The species is probably a bottom feeder which locates its food primarily by taste (Pflieger 1975).

Ecology

Montana apparently marks the upstream limit of the Sicklefin Chub's range (Holton 1980, 1990).

Reproductive Characteristics

The species reaches a maximum age of 4 years and generally becomes sexually mature at the age of 2. Spawning occurs in main channel areas of large, turbid rivers which they inhabit. The spawning period is in the summer months and probably occurs over a wide time span, similar to other big river species. Although sympatric, there is no information that suggests this species hybridizes with the other member of its genus, the Sturgeon Chub (

Macrhybopsis gelida) (

Montana AFS Species Status Account).

Management

December 20th, 2017 the US Fish and Wildlife Service published a notice announcing a substantial finding on the listing petition for this species in the Federal Register (82 FR 60364). On September 20th, 2023 the The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published a not-warranted 12-month finding in the

Federal Register.

The management of this species should involve routine monitoring (once every 2 to 3 years) of existing populations. The program should be designed to monitor population trends, range expansion or losses and collect additional information on life history and ecology. This could be conducted while sampling for other species. The lack of proper monitoring of these populations could lead to their demise by virtue of not recognizing if and when they are in jeopardy of becoming extirpated by any artificial or natural entity. Recommendations for operating reservoir and irrigation projects should be developed for improving and maintaining Sicklefin Chub populations and habitats in Montana (

Montana AFS Species Status Account).

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Major threats to the Sicklefin Chub and other large river fishes are habitat and flow alterations from dams, diversions, irrigation operations and riparian development (Rinne et al. 2005). Sicklefin Chubs need main channel gravel and sand runs in turbid running waters for their life history requirements(Pflieger 1975), thus decreased flows and excessive siltation of gravels are threats facing all lithophilic spawning fish species (Waters 1995). Reservoirs created behind dams inundate riverine habitats and replace the river with lentic conditions, which is unsuitable habitat for Sturgeon Chubs. Dams also create unsuitable habitat for Sicklefin Chubs downstream by reducing turbidities and/or altering temperature and flow regimes (Ruggles, pers. comm). Fortunately for this species, it appears unlikely that any new dams will be built on the Yellowstone or Missouri rivers in Montana in the foreseeable future. However, water regulation at Fort Peck Dam and several other tributary dams (intake on the Yellowstone) continue to limit the distribution and abundance of some fish populations in Montana by fragmenting populations and restricting spawning and migration patterns (Rinne et al. 2005, Ruggles, personal communication).

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Holton, G. D. 1980. The riddle of existence: fishes of special concern. Montana Outdoors 11(1):2-6.

Holton, G. D. 1980. The riddle of existence: fishes of special concern. Montana Outdoors 11(1):2-6. Holton, G.D. 1981. Identification of Montana's most common game and sport fishes. Montana Outdoors May/June reprint. 8 p.

Holton, G.D. 1981. Identification of Montana's most common game and sport fishes. Montana Outdoors May/June reprint. 8 p. Lee, D.S., C.R. Gilbert, C.H. Hocutt, R.E. Jenkins, D. E. McAllister, J. R. Stauffer, Jr. 1980. Atlas of North American freshwater fishes. North Carolina State Musuem of Natural History. 867 p.

Lee, D.S., C.R. Gilbert, C.H. Hocutt, R.E. Jenkins, D. E. McAllister, J. R. Stauffer, Jr. 1980. Atlas of North American freshwater fishes. North Carolina State Musuem of Natural History. 867 p. Montana Chapter of the American Fisheries Society species status accounts.

Montana Chapter of the American Fisheries Society species status accounts. Pflieger, W. L. 1975. The Fishes of Missouri. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City. 343 pp.

Pflieger, W. L. 1975. The Fishes of Missouri. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City. 343 pp. Rinne, J., R. Hughes and B. Calamusso, eds. 2005. Historical changes in large river fish assemblages of the Americas. Published by American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, MD. 612 pp.

Rinne, J., R. Hughes and B. Calamusso, eds. 2005. Historical changes in large river fish assemblages of the Americas. Published by American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, MD. 612 pp. Scott, W.B. and E.J. Crossman. 1973. Rainbow trout, Kamloops trout, Steelhead trout Salmo gairdneri Richardson. pp. 184-191. In: Freshwater fishes of Canada. Ottawa, Canada: Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Bulletin 184. 966 p.

Scott, W.B. and E.J. Crossman. 1973. Rainbow trout, Kamloops trout, Steelhead trout Salmo gairdneri Richardson. pp. 184-191. In: Freshwater fishes of Canada. Ottawa, Canada: Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Bulletin 184. 966 p. Waters, T.F. 1995. Sediment in streams: Sources, biological effects, and control. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland. Monograph 7.

Waters, T.F. 1995. Sediment in streams: Sources, biological effects, and control. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland. Monograph 7.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Bramblett, R.G. 1996. Habitats and movements of pallid and shovelnose sturgeon in the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers, Montana and North Dakota. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 210 p.

Bramblett, R.G. 1996. Habitats and movements of pallid and shovelnose sturgeon in the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers, Montana and North Dakota. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 210 p. Dieterman, D.J., M.P. Ruggles, M.L. Wildhaber, and D.L. Galat (eds). 1996. Population structure and habitat use of benthic fishes along the Missouri and Lower Yellowstone Rivers. 1996 Annual report of Missouri River Benthic Fish Study PD-95-5832 to U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 238 p.

Dieterman, D.J., M.P. Ruggles, M.L. Wildhaber, and D.L. Galat (eds). 1996. Population structure and habitat use of benthic fishes along the Missouri and Lower Yellowstone Rivers. 1996 Annual report of Missouri River Benthic Fish Study PD-95-5832 to U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 238 p. Duncan, M.B. 2019. Distributions, abundances, and movements of small, nongame fishes in a large Great Plains river network. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 255 p.

Duncan, M.B. 2019. Distributions, abundances, and movements of small, nongame fishes in a large Great Plains river network. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 255 p. Gould, W.R. 1981. First records of the rainbow smelt (Osmeridae), sicklefin chub (Cyphnidae), and white bass (Percichthyidge) from Montana. Proc. MT. Acad. Sci. 40:9-10.

Gould, W.R. 1981. First records of the rainbow smelt (Osmeridae), sicklefin chub (Cyphnidae), and white bass (Percichthyidge) from Montana. Proc. MT. Acad. Sci. 40:9-10. Grisak, G. 1999. Population status of the sicklefin chub in Montana. 4 p. In: Tews, A., B. Gardner and B. Gardner. Status of Native Fishes of 'Special Concern' in Montana. Unpublished Report on 16 Species.

Grisak, G. 1999. Population status of the sicklefin chub in Montana. 4 p. In: Tews, A., B. Gardner and B. Gardner. Status of Native Fishes of 'Special Concern' in Montana. Unpublished Report on 16 Species. Grisak, G.G. 1996. The status and distribution of the sicklefin chub in the middle Missouri River, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 77 p.

Grisak, G.G. 1996. The status and distribution of the sicklefin chub in the middle Missouri River, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 77 p. Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. Werdon, S.J. 1993. Status report on sicklefin chub (Macrhybopsis meeki) a candidate endangered species. Bismark, ND: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Ecological Services. 41 p.

Werdon, S.J. 1993. Status report on sicklefin chub (Macrhybopsis meeki) a candidate endangered species. Bismark, ND: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Ecological Services. 41 p. Young, B.A., T.L. Welker, M.L. Wildhaber, C.R. Berry, and D. Scarnecchia (eds). 1997. Population structure and habitat use of benthic fishes along the Missouri and Lower Yellowstone Rivers. 1997 Annual report of Missouri River Benthic Fish Study PD-95-5832 to U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 207 p.

Young, B.A., T.L. Welker, M.L. Wildhaber, C.R. Berry, and D. Scarnecchia (eds). 1997. Population structure and habitat use of benthic fishes along the Missouri and Lower Yellowstone Rivers. 1997 Annual report of Missouri River Benthic Fish Study PD-95-5832 to U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 207 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Sicklefin Chub"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Fish"