View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Smooth Greensnake - Opheodrys vernalis

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

The Smooth Green Snake is rarely observed and is only found within or near wetland habitat in far northeastern Montana. Conversion of grassland habitat to cropland threatens the species persistence within the state. Like many other reptiles we do not have data to assess changes in population, occupancy, or distribution over time.

General Description

EGGS:

Females are oviparous, laying one or two clutches of eggs (Smith 1963). Clutch sizes vary from 3 to 12 eggs, averaging approximately 7 (Hammerson 1999, Ernst and Ernst 2003). Eggs are white and oval with thin shells and blunt ends; approximately 25 cm (1 in.) (Werner et al. 2004).

HATCHLINGS:

Recently hatched neonates may have gray, olive, or brown backs. They range in size from 8.3- 6.7 cm (3.3-6.6 in.) and a mean of 13.3 cm (5.2 in.) total length (TL) (Wright and Wright 1957, Smith 1963, Conant and Collins 1991, Powell et al. 1998, Ernst and Ernst 2003, Stebbins 2003, Werner et al. 2004).

JUVENILES AND ADULTS:

This species is small, thin, bright green snake with no pattern, smooth (unkeeled) dorsal scales and a uniform white to cream ventral surface, sometimes becoming yellowish toward the tail. The anal plate is divided, and there is a single anterior temporal scale. There are usually eight (occasionally seven) lower labials and usually seven (occasionally six) yellowish upper labials. Each nostril is centered within a single scale. There are 15 midbody dorsal scale rows, 106-154 ventrals, and 59-102 subcaudals. Individuals rarely exceed 50 cm (20 in.) TL, but females are generally larger and have been known to reach 80 cm (32 in.) TL. Females can become sexually mature as short as 28 cm (11 in.) TL, while males may mature at 30 cm (11.8 in) TL. Dead or preserved specimens turn bluish (St. John 2002).

Diagnostic Characteristics

Eastern Racers (

Coluber constrictor) also have unkeeled scales and are a generally a uniform green in Montana, but they are always much larger as adults. Hatchling and juvenile Eastern Racers, which may be similar in size to Smooth Greensnakes, but have a distinct banded or blotched pattern before they mature. Unlike

Opheodrys vernalis, the Eastern Racer has two anterior temporal scales, and each nostril is centered between two scales. Additionally,

C. constrictor has an elongated preocular scale that enters the upper labial row (Degenhardt et al. 1996, Ernst and Ernst 2003, Stebbins 2003, Werner et al. 2004).

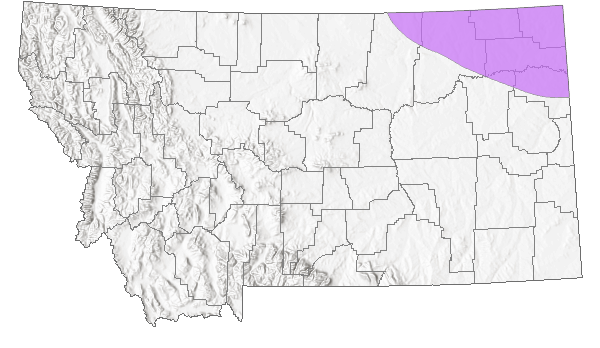

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Western Hemisphere Range

Range Comments

The Smooth Greensnake has a mostly continuous range throughout the northeastern United States from Nova Scotia south to northern Virginia and northwesterly to the upper Midwest, where its range becomes widely scattered further west and south. Isolated populations exist as far west as Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico, and as far south as Texas and part of Mexico (Ernst and Ernst 2003, Stebbins 2003). In Montana, Smooth Greensnakes have been observed from only three northeastern counties: Sheridan, Daniels, and Roosevelt Counties and includes 57 observations (Black and Bragg 1968, Hendricks 1999a, Maxell et al. 2003, MTNHP 2024). These observations are located on the periphery of their range, crossing the Saskatchewan and North Dakota borders into Montana’s Glaciated Dark Brown Prairie and Coteau Lakes Upland Ecoregions (Woods et al. 2002). Three subspecies have been proposed (including O. v. blanchardi in Montana) based primarily on clinal variation in numbers of ventral and caudal scales (Grobman 1941, Smith 1963, Grobman 1992a, Grobman 1992b). However, these subspecies are currently unrecognized by most herpetologists due to overlap in morphology and a lack of molecular evidence (Collins 1992). Additionally, some herpetologists have designated a new genus, Liochlorophis, for the Smooth Greensnake based on morphological and physiological differences between it and the Rough Greensnake (O. aestivus) (Oldham and Smith 1991, Hammerson 1999).

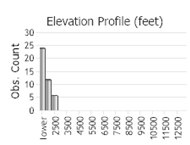

Maximum Elevation: 853 m (2,797 ft) in Daniels County, H. Bower (MTNHP 2024).

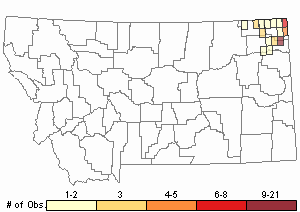

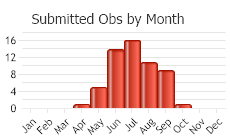

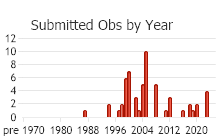

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 63

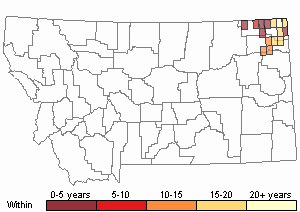

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

No information specific to Montana is known, but based upon habits in other areas of the species' range, the Smooth Greensnake may migrate between winter hibernaculum and summer range in some areas (Vogt 1981).

Habitat

Smooth Greensnakes prefer mesic habitat such as wet prairies, meadows, marshes, open forests, and riparian corridors with lush shrubby and herbaceous cover. They are secretive, and often found under cover objects such as logs, bark, boards, and rocks (Smith 1963, Hammerson 1999, Ernst and Ernst 2003). Periods of inactivity are spent underground, beneath woody debris and rocks, or in rotting wood. They have been found hibernating in abandoned ant mounds. Most activity is restricted to the ground, but they may climb into low vegetation, and sometimes enter water (Hammerson 1999). This species may also be found in damp meadows bordering streams and lakes as well as drier, rocky areas, but usually only if grass or similar vegetation is present. Little information is available for the species in Montana, though it has been reported from residential lawns, city parks, along ditches in prairie pothole country, and around wetland complexes. Home range, population, and migratory data is absent in Montana and lacking elsewhere. In the Midwest, Smooth Greensnakes are thought to be locally common at some locations but appear to be becoming rare or extirpated in others (Harding 1997).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Forest and Woodland

Deciduous Forest and Woodland

Grassland

Lowland - Prairie Grassland

Wetland and Riparian

Alkaline - Saline Wetlands

Peatland

Riparian and Wetland Forest

Riparian Shrubland

Wet Meadow and Marsh

Recently Disturbed or Modified

Introduced Vegetation

Human Land Use

Developed

Food Habits

Smooth Greensnakes primarily prey on invertebrates, particularly small insects. Documented prey includes ants, maggots, grasshoppers, crickets, beetles, grubs, spiders, centipedes, millipedes, slugs, snails, salamanders, and small crayfish (Wright and Wright 1957, Hammerson 1999, Ernst and Ernst 2003). Nothing is known regarding food habits in Montana.

Ecology

Smooth Greensnakes are primarily diurnal, with most activity occurring at warmer times of the day, although they have been observed in the evening on warm asphalt (Hammerson 1999). In Illinois, Seibert and Hagen (1947) found they were most active at air temperatures between 21-30 °C (69.8-86 F). Smooth Greensnakes are primarily ground dwellers but have been known to climb into low shrubs to bask or forage (Degenhardt et al. 1996, Ernst and Ernst 2003). Multiple individuals are often found together under objects, suggesting they are somewhat communal.

Overwintering usually takes place in September at northern latitudes. They have been observed conducting prehibernation movements as early as late August between 1,524 and 1,829 m (5,000 and 6,000 ft) in the Black Hills, South Dakota (Smith 1963) and during September in Colorado (Hammerson 1999), and probably in Montana as well (Maxell et al. 2003), although little is known about its ecology in Montana. Overwintering occurs underground, and has been observed in ant mounds, mammal burrows, gravel banks, and spaces between granite slabs.

O. vernalis may hibernate communally with other species, including (

Thamnophis radix) and (

T. sirtalis) (Criddle 1937, Lachner 1942, Degenhardt et al. 1996, Ernst and Ernst 2003).

Their cryptic green coloration helps them avoid detection from predators. If cornered or seized, their last modes of defense are the release foul smelling cloacal secretions, and sometimes they will gape their mouths and pretend to strike, although they never bite (Cochran 1987b, Hammerson 1999). The first voucher specimen in the state was probably killed by hail. Documented predators include gartersnakes (

Thamnophis spp.), chickens, hawks (

Buteo spp.), and cats. Reported predators in Montana include Loggerhead Shrike (

Lanius ludovicianus) and Brown Thrasher (

Toxostoma rufum).

Reproductive Characteristics

Smooth Greensnakes emerge from hibernacula in late spring to early summer. Data on post-emergence behavior and courtship is absent in Montana and poorly documented elsewhere. However, mating is known to occur shortly after emergence in May but has been observed as early as April 15th in Pennsylvania (Ernst and Ernst 2003), and as late as August in southern Ontario, Canada. Females inseminated in late summer or fall probably store their sperm overwinter before fertilization occurs in the spring, as with other colubrid snakes (Dymond and Fry 1932, Hammerson 1999, Werner et al. 2004). Data collected by Smith et al. (1991) in Colorado suggest that females do not reproduce every year and that sexual maturity is not reached until the third calendar year or when females reach 22-26 cm (8.7-10.2 in.) snout-vent length (Hammerson 1999). Females are oviparous, laying one or two clutches of eggs under stones, boards, logs, and inside rotting wood (Smith 1963). Northern populations typically oviposit from late July through August, although no data exists for Montana. Eggs are typically incubated for 3-4 weeks before hatching, but Michigan females have oviposited very late in embryogenesis, just four days prior to hatching. In Michigan and Ontario, clutch sizes varied from 3 to 18 eggs, averaging approximately 7 (Hammerson 1999, Ernst and Ernst 2003). Females will occasionally nest communally at high quality nest sites (Fitch 1970, Hammerson 1999). Egg-groups numbering 27 and 31, each from three different females have been found in choice nest-sites in rotting logs (Cook 1964, Fowler 1966). In Manitoba, Gregory (1975a) located three gravid females near, each with five eggs, in a good nest site underneath a wooden platform. Grobman (1989) found that larger females deposit more eggs than smaller females, and that in eastern populations clutch size decreases with an increase in latitude. This suggests that Montana females probably produce fewer eggs on average than populations studied at lower latitudes.

Management

The following was taken from the Status and Conservation section for the Smooth Greensnake account in

Maxell et al. 2009.

In Montana, Smooth Greensnakes have a very restricted range, occupying a portion of just the three northeastern counties. There have only been 43 recorded observations, but 35 of those have come in the last 10 years. This lack of records may reflect a low abundance at the periphery of their range, or simply a lack of reported sightings and formal surveys in the region, which is sparsely populated and dominated by private lands. (1) Smooth Greensnakes consume large numbers of insects and are therefore probably most successful where they are plentiful. In Montana, they are found in a very small region primarily used for grazing and crop production. Therefore, heavy use of insecticides is a concern since it may affect this species both by direct poisoning and indirectly through prey reduction. In Indiana, Minton (1972) reported that two Smooth Greensnakes died from direct poisoning after insecticide application (Ernst and Ernst 2003). (2) Over-grazing, especially along riparian corridors, can trample and alter vegetation and soil structure, which are important components of

O. vernalis habitat, and therefore could affect local populations. Grazing is known to reduce the abundance of many invertebrates (Hutchinson and King 1980), which could directly affect prey availability for

O. vernalis. (3) Although effects of road mortality have not been directly studied in

O. vernalis, studies on other snakes indicate roads often have negative impacts on population size and distribution. High road density has been positively correlated to low population size, which leads to populations being restricted to pockets with low road density. This may lead to isolation or restricted interaction between populations (Rudolph et al. 1998, Jochimsen et al. 2004). This is of particular concern in Montana, where Smooth Greensnakes appear to be rare, and are found within a very restricted area.

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Black, J.H., and A.N. Bragg. 1968. New additions to the herpetofauna of Montana. Herpetologica 24: 247.

Black, J.H., and A.N. Bragg. 1968. New additions to the herpetofauna of Montana. Herpetologica 24: 247. Cochran, P.A. 1987b. Opheodrys vernalis (smooth green snake). Behavior. Herpetological Review 18(2): 36-37.

Cochran, P.A. 1987b. Opheodrys vernalis (smooth green snake). Behavior. Herpetological Review 18(2): 36-37. Collins, J.T. 1992. Reply to Grobman on variation in Opheodrys aestivus. Herpetological Review 23:15-16.

Collins, J.T. 1992. Reply to Grobman on variation in Opheodrys aestivus. Herpetological Review 23:15-16. Conant, R. and J.T. Collins. 1991. A field guide to reptiles and amphibians of eastern and central North America. Third edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. Boston, MA. 450 pp.

Conant, R. and J.T. Collins. 1991. A field guide to reptiles and amphibians of eastern and central North America. Third edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. Boston, MA. 450 pp. Cook, F.R. 1964. Communal egg laying in the smooth green snake. Herpetologica 20: 206.

Cook, F.R. 1964. Communal egg laying in the smooth green snake. Herpetologica 20: 206. Criddle, S. 1937. Snakes from an ant hill. Copeia 2:142.

Criddle, S. 1937. Snakes from an ant hill. Copeia 2:142. Degenhardt, W. G., C. W. Painter, and A. H. Price. 1996. Amphibians and reptiles of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Degenhardt, W. G., C. W. Painter, and A. H. Price. 1996. Amphibians and reptiles of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. Ernst, C.H. and E.M. Ernst. 2003. Snakes of the United States and Canada. New York, New York. Harper Collins Publishers. 680 p.

Ernst, C.H. and E.M. Ernst. 2003. Snakes of the United States and Canada. New York, New York. Harper Collins Publishers. 680 p. Fitch, H.S. 1970. Reproductive cycles in lizards and snakes. University of Kansas. Museum Natural History Miscellaneous Publication 52:1-247.

Fitch, H.S. 1970. Reproductive cycles in lizards and snakes. University of Kansas. Museum Natural History Miscellaneous Publication 52:1-247. Fowler, J.A. 1966. A communal nesting site for the smooth green snake in Michigan. Herpetologica 22: 231.

Fowler, J.A. 1966. A communal nesting site for the smooth green snake in Michigan. Herpetologica 22: 231. Gregory, P.T. 1977a. Life history observations of three species of snakes in Manitoba. Canadian Field Naturalist 91(1): 19-27.

Gregory, P.T. 1977a. Life history observations of three species of snakes in Manitoba. Canadian Field Naturalist 91(1): 19-27. Grobham, A.B. 1989. Clutch size and female length in Opheodrys vernalis. Herpetological Review 20(4): 84-85.

Grobham, A.B. 1989. Clutch size and female length in Opheodrys vernalis. Herpetological Review 20(4): 84-85. Grobman, A. 1992b. On races, clines, and common names in Opheodrys. Herpetological Review 23:14-15.

Grobman, A. 1992b. On races, clines, and common names in Opheodrys. Herpetological Review 23:14-15. Grobman, A.B. 1941. A contribution to the knowledge of variation in (Opheodrys vernalis) (Harlan), with the description of a new subspecies. Miscellaneous Publications Museum of Zoolology, University of Michigan 50: 7-38.

Grobman, A.B. 1941. A contribution to the knowledge of variation in (Opheodrys vernalis) (Harlan), with the description of a new subspecies. Miscellaneous Publications Museum of Zoolology, University of Michigan 50: 7-38. Grobman, A.B. 1992a. Metamerism in the snake Opheodrys vernalis, with a description of a new subspecies. Journal of Herpetology 26(2): 175-186.

Grobman, A.B. 1992a. Metamerism in the snake Opheodrys vernalis, with a description of a new subspecies. Journal of Herpetology 26(2): 175-186. Hammerson, G.A. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. University Press of Colorado & Colorado Division of Wildlife. Denver, CO. 484 p.

Hammerson, G.A. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. University Press of Colorado & Colorado Division of Wildlife. Denver, CO. 484 p. Harding, J. H. 1997. Amphibians and reptiles of the Great Lakes region. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. xvi + 378 pp.

Harding, J. H. 1997. Amphibians and reptiles of the Great Lakes region. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. xvi + 378 pp. Hendricks, P. 1999a. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Bureau of Land Management Miles City District, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 80 p.

Hendricks, P. 1999a. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Bureau of Land Management Miles City District, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 80 p. Hutchinson, K.J., and Kathleen L. King. 1980. The effects of sheep stocking level on invertebrate abundance, biomass and energy utilization in a temperate, south grassland. Journal of Applied Ecology. 17:369-387.

Hutchinson, K.J., and Kathleen L. King. 1980. The effects of sheep stocking level on invertebrate abundance, biomass and energy utilization in a temperate, south grassland. Journal of Applied Ecology. 17:369-387. Jochimsen, D.M., C.R. Peterson, K.M. Andrews, and J.W. Gibbons. 2004. A literature review of the effects of roads on amphibians and reptiles and the measures used to minimize those effects. Final Draft, Idaho Fish and Game Department, USDA Forest Service.

Jochimsen, D.M., C.R. Peterson, K.M. Andrews, and J.W. Gibbons. 2004. A literature review of the effects of roads on amphibians and reptiles and the measures used to minimize those effects. Final Draft, Idaho Fish and Game Department, USDA Forest Service. Lachner, E.A. 1942. An aggregation of snakes and salamanders during hibernation. Copeia 4:262-263.

Lachner, E.A. 1942. An aggregation of snakes and salamanders during hibernation. Copeia 4:262-263. Maxell, B.A., J.K. Werner, P. Hendricks, and D.L. Flath. 2003. Herpetology in Montana: a history, status summary, checklists, dichotomous keys, accounts for native, potentially native, and exotic species, and indexed bibliography. Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology, Northwest Fauna Number 5. Olympia, WA. 135 p.

Maxell, B.A., J.K. Werner, P. Hendricks, and D.L. Flath. 2003. Herpetology in Montana: a history, status summary, checklists, dichotomous keys, accounts for native, potentially native, and exotic species, and indexed bibliography. Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology, Northwest Fauna Number 5. Olympia, WA. 135 p. Maxell, B.A., P. Hendricks, M.T. Gates, and S. Lenard. 2009. Montana amphibian and reptile status assessment, literature review, and conservation plan, June 2009. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 643 p.

Maxell, B.A., P. Hendricks, M.T. Gates, and S. Lenard. 2009. Montana amphibian and reptile status assessment, literature review, and conservation plan, June 2009. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 643 p. Minton, S. A., Jr. 1972. Amphibians and reptiles of Indiana. Indiana Acad. Sci. Monogr. 3. 346 pp.

Minton, S. A., Jr. 1972. Amphibians and reptiles of Indiana. Indiana Acad. Sci. Monogr. 3. 346 pp. Oldham, J.C. and H.M. Smith. 1991. The generic status of the smooth green snake, Opheodrys vernalis. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 27(4): 201-215.

Oldham, J.C. and H.M. Smith. 1991. The generic status of the smooth green snake, Opheodrys vernalis. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 27(4): 201-215. Powell, R., J.T. Collins, and E.D. Hooper, Jr. 1998. A key to amphibians and reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. 131 p.

Powell, R., J.T. Collins, and E.D. Hooper, Jr. 1998. A key to amphibians and reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS. 131 p. Rudolph, D.C., S.J. Burdorf, R.N. Conner, and J.G. Dickson. 1998. The impact of roads on the timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus), in Eastern Texas. pp. 236-240. In: G.L. Evink, P. Garrett, D. Zeigler, and J. Berry (eds). Proceedings of the international conference on wildlife ecology.

Rudolph, D.C., S.J. Burdorf, R.N. Conner, and J.G. Dickson. 1998. The impact of roads on the timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus), in Eastern Texas. pp. 236-240. In: G.L. Evink, P. Garrett, D. Zeigler, and J. Berry (eds). Proceedings of the international conference on wildlife ecology. Seibert, H.C. and Hagen, W. Jr. 1947. Studies on a population of snakes in Illinois. Copeia (1) 6-22.

Seibert, H.C. and Hagen, W. Jr. 1947. Studies on a population of snakes in Illinois. Copeia (1) 6-22. Smith, H.M. 1963. The taxonomic status of the Black Hills population of smooth greensnakes. Herpetologica 19(4): 256-261.

Smith, H.M. 1963. The taxonomic status of the Black Hills population of smooth greensnakes. Herpetologica 19(4): 256-261. Smith, H.M., G.A. Hammerson, J.J. Roth, and D. Chiszar. 1991. Distributional addenda for the smooth green snake (Opheodrys vernalis) in western Colorado, and the status of its subspecies. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 27(2): 99-106.

Smith, H.M., G.A. Hammerson, J.J. Roth, and D. Chiszar. 1991. Distributional addenda for the smooth green snake (Opheodrys vernalis) in western Colorado, and the status of its subspecies. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 27(2): 99-106. St. John, A.D. 2002. Reptiles of the northwest: California to Alaska, Rockies to the coast. Lone Pine Publishing, Renton, WA. 272 p.

St. John, A.D. 2002. Reptiles of the northwest: California to Alaska, Rockies to the coast. Lone Pine Publishing, Renton, WA. 272 p. Stebbins, R. C. 2003. A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York. 533 p.

Stebbins, R. C. 2003. A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York. 533 p. Vogt, R. C. 1981. Natural history of amphibians and reptiles of Wisconsin. Milwaukee Public Museum. 205 p.

Vogt, R. C. 1981. Natural history of amphibians and reptiles of Wisconsin. Milwaukee Public Museum. 205 p. Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks and D.L. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and Reptiles of Montana. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, MT. 262 pp.

Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks and D.L. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and Reptiles of Montana. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, MT. 262 pp. Woods, A. J., J. M. Omernick, J. A. Nesser, J. Shelden, J. A. Comstock, and S. H. Azevedo. 2002. Ecoregions of Montana, 2nd edition (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs). Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, Durham, North Carolina.

Woods, A. J., J. M. Omernick, J. A. Nesser, J. Shelden, J. A. Comstock, and S. H. Azevedo. 2002. Ecoregions of Montana, 2nd edition (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs). Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, Durham, North Carolina. Wright, A.H. and A.A. Wright. 1957. Handbook of snakes of the United States and Canada. Comstock Publ. Assoc., Ithaca, New York. 2 vols. Xxvii + 1105p.

Wright, A.H. and A.A. Wright. 1957. Handbook of snakes of the United States and Canada. Comstock Publ. Assoc., Ithaca, New York. 2 vols. Xxvii + 1105p.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Baxter, G.T. and M.D. Stone. 1985. Amphibians and reptiles of Wyoming. Second edition. Wyoming Game and Fish Department. Cheyenne, WY. 137 p.

Baxter, G.T. and M.D. Stone. 1985. Amphibians and reptiles of Wyoming. Second edition. Wyoming Game and Fish Department. Cheyenne, WY. 137 p. Black, J.H. and R. Timken. 1976. Endangered and threatened amphibians and reptiles in Montana. p 36–37. In R.E. Ashton, Jr. (chair). Endangered and threatened amphibians and reptiles in the United States. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Herpetological Circular 5: 1-65.

Black, J.H. and R. Timken. 1976. Endangered and threatened amphibians and reptiles in Montana. p 36–37. In R.E. Ashton, Jr. (chair). Endangered and threatened amphibians and reptiles in the United States. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Herpetological Circular 5: 1-65. Blahnik, J.F. and P.A. Cochran. 1994. Opheodrys vernalis (smooth green snake). Herpetological Review 25(2): 77.

Blahnik, J.F. and P.A. Cochran. 1994. Opheodrys vernalis (smooth green snake). Herpetological Review 25(2): 77. Blanchard, F.N. 1933. Eggs and young of the smooth green snake, Liopeltis vernalis. Papers of the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts and Letters 27: 493-508.

Blanchard, F.N. 1933. Eggs and young of the smooth green snake, Liopeltis vernalis. Papers of the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts and Letters 27: 493-508. Brodman, R., S. Cortwright, and A. Resetar. 2002. Historical changes of reptiles and amphibians of northwest Indiana fish and wildlife properties. American Midland Naturalist 147:135-144.

Brodman, R., S. Cortwright, and A. Resetar. 2002. Historical changes of reptiles and amphibians of northwest Indiana fish and wildlife properties. American Midland Naturalist 147:135-144. Brown, L.E. 1994. Occurrence of smooth green snakes in a highly polluted microenvironment in central Illinois prairie. Prairie Naturalist 26(2): 155-156.

Brown, L.E. 1994. Occurrence of smooth green snakes in a highly polluted microenvironment in central Illinois prairie. Prairie Naturalist 26(2): 155-156. Brunson, R.B. 1955. Check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 15: 27-29.

Brunson, R.B. 1955. Check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 15: 27-29. Carlson, J. (Coordinator, Montana Animal Species of Concern Committee). 2003. Montana Animal Species of Concern January 2003. Helena, MT: Montana Natural Heritage Program and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. In Press. 12p.

Carlson, J. (Coordinator, Montana Animal Species of Concern Committee). 2003. Montana Animal Species of Concern January 2003. Helena, MT: Montana Natural Heritage Program and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. In Press. 12p. Casper, G.S. 1996. Opheodrys vernalis (smooth green snake). Herpetological Review 27(4): 214.

Casper, G.S. 1996. Opheodrys vernalis (smooth green snake). Herpetological Review 27(4): 214. Collins, J.T. 1990. Standard common and current scientific names for North American amphibians and reptiles. 3rd ed. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Herpetological Circular 19: 41 pp.

Collins, J.T. 1990. Standard common and current scientific names for North American amphibians and reptiles. 3rd ed. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. Herpetological Circular 19: 41 pp. Cooper, J. G. 1869. The fauna of Montana Territory (concluded) III. Reptiles, IV Fish. American Naturalist 3(3):124-127

Cooper, J. G. 1869. The fauna of Montana Territory (concluded) III. Reptiles, IV Fish. American Naturalist 3(3):124-127 Coues, E. and H. Yarrow. 1878. Notes on the herpetology of Dakota and Montana. Bulletin of the U.S. Geological Geographic Survey of the Territories 4: 259-291.

Coues, E. and H. Yarrow. 1878. Notes on the herpetology of Dakota and Montana. Bulletin of the U.S. Geological Geographic Survey of the Territories 4: 259-291. Cox, D.L., T.J. Koob, R.P. Mecham, and O.J. Sexton. 1984. External incubation alters the composition of squamate egg-shells. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology B Comparative Biochemisty 79(3): 481-488.

Cox, D.L., T.J. Koob, R.P. Mecham, and O.J. Sexton. 1984. External incubation alters the composition of squamate egg-shells. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology B Comparative Biochemisty 79(3): 481-488. Crother, B.I. (ed.) 2008. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico. SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 37:1-84.

Crother, B.I. (ed.) 2008. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico. SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 37:1-84. Cundall, D. 1986. Variations of the cephalic muscles in the colubrid snake genera Entechinus, Opheodrys, and Symphimus. Journal of Morphology 187(1): 1-21.

Cundall, D. 1986. Variations of the cephalic muscles in the colubrid snake genera Entechinus, Opheodrys, and Symphimus. Journal of Morphology 187(1): 1-21. DeFusco, R.P., D. Chiszar, and H.M. Smith. 1994. Liochlorophis vernalis blanchardi (smooth green snake). Herpetological Review 25(2): 77.

DeFusco, R.P., D. Chiszar, and H.M. Smith. 1994. Liochlorophis vernalis blanchardi (smooth green snake). Herpetological Review 25(2): 77. Dymond, J.R. and F.E.J. Fry. 1932. Notes on the breeding habits of the green snake (Liopeltis vernalis). Copeia 2:102.

Dymond, J.R. and F.E.J. Fry. 1932. Notes on the breeding habits of the green snake (Liopeltis vernalis). Copeia 2:102. Finch, D.M. 1992. Threatened, endangered, and vulnerable species of terrestrial vertebrates in the Rocky Mountain Region. General Technical Report RM-215. USDA, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Ft. Collins CO. 38 p.

Finch, D.M. 1992. Threatened, endangered, and vulnerable species of terrestrial vertebrates in the Rocky Mountain Region. General Technical Report RM-215. USDA, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Ft. Collins CO. 38 p. Flath, D.L. 1998. Species of special interest or concern. Montana Department of Fish, Widlife and Parks, Helena, MT. March, 1998. 7 p.

Flath, D.L. 1998. Species of special interest or concern. Montana Department of Fish, Widlife and Parks, Helena, MT. March, 1998. 7 p. Gordon, D.M. and F.R. Cook. 1980. An aggregation of gravid snakes in the Quebec Laurentians. Canadian Field Naturalist 94(4): 456-457.

Gordon, D.M. and F.R. Cook. 1980. An aggregation of gravid snakes in the Quebec Laurentians. Canadian Field Naturalist 94(4): 456-457. Grobman, A.B. 1991. Does the smooth green snake occur in Missouri? Transactions of the Missouri Academy of Science 25(0): 1-3.

Grobman, A.B. 1991. Does the smooth green snake occur in Missouri? Transactions of the Missouri Academy of Science 25(0): 1-3. Groves, John D. 1977. A note on the eggs and young of the smooth green snake, /Opheodrys vernalis/ in Maryland. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 12(4): 131-132.

Groves, John D. 1977. A note on the eggs and young of the smooth green snake, /Opheodrys vernalis/ in Maryland. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 12(4): 131-132. Harlan, R. 1827. Genera of North American Reptilia, and a synopsis of the species. Journal of the Academy of National Sciences, Philadelphia 5: 317-372; 6: 7-38.

Harlan, R. 1827. Genera of North American Reptilia, and a synopsis of the species. Journal of the Academy of National Sciences, Philadelphia 5: 317-372; 6: 7-38. Hayden, F.V. 1858. Catalogue of the collections in geology and natural history, obtained by the expedition under command of Lieutenant G.K. Warren, Topographical Engineers. pp. 104-105. In: F.N. Shubert (1981) Explorer on the northern plains: Lieutenant Gouverneur K. Warren's preliminary report of explorations in Nebraska and Dakota, in the years 1855-'56-'57. Engineer Historical Studies No. 2. Office of the Chief of Engineers, Washington, DC. 125 p.

Hayden, F.V. 1858. Catalogue of the collections in geology and natural history, obtained by the expedition under command of Lieutenant G.K. Warren, Topographical Engineers. pp. 104-105. In: F.N. Shubert (1981) Explorer on the northern plains: Lieutenant Gouverneur K. Warren's preliminary report of explorations in Nebraska and Dakota, in the years 1855-'56-'57. Engineer Historical Studies No. 2. Office of the Chief of Engineers, Washington, DC. 125 p. Hayden, F.V. 1862. On the geology and natural history of the upper Missouri. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society New Series 12(1): 1-218

Hayden, F.V. 1862. On the geology and natural history of the upper Missouri. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society New Series 12(1): 1-218 Hendricks, P., S. Lenard, D.M. Stagliano, and B.A. Maxell. 2013. Baseline nongame wildlife surveys on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation. Report to the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 83 p.

Hendricks, P., S. Lenard, D.M. Stagliano, and B.A. Maxell. 2013. Baseline nongame wildlife surveys on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation. Report to the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 83 p. Holman, J.A. and F. Grady. 1994. A Pleistocene herpetofauna from Worm Hole Cave, Pendleton County, West Virginia. NSS Bulletin 56(1): 46-49.

Holman, J.A. and F. Grady. 1994. A Pleistocene herpetofauna from Worm Hole Cave, Pendleton County, West Virginia. NSS Bulletin 56(1): 46-49. Holman, J.A. and R.L. Richards. 1981. Late pleistocene occurrence in southern Indiana of the smooth green snake, Opheodrys vernalis. Journal of Herpetology 15(1): 123-125.

Holman, J.A. and R.L. Richards. 1981. Late pleistocene occurrence in southern Indiana of the smooth green snake, Opheodrys vernalis. Journal of Herpetology 15(1): 123-125. Hossack, B. and P.S. Corn. 2001. Amphibian survey of Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge Complex: 2001. USGS Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, Missoula, MT. 13 p.

Hossack, B. and P.S. Corn. 2001. Amphibian survey of Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge Complex: 2001. USGS Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, Missoula, MT. 13 p. Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. Lawson, R. 1983. Opheodrys vernalis (smooth green snake). Reproduction. Herpetological Review 14(1): 20.

Lawson, R. 1983. Opheodrys vernalis (smooth green snake). Reproduction. Herpetological Review 14(1): 20. Livo, L.J., D. Chiszar, and H.M. Smith. 1996. Liochlorophis (=Opheodrys) vernalis (smooth green snake). Herpetol. Rev. 27(3):154.

Livo, L.J., D. Chiszar, and H.M. Smith. 1996. Liochlorophis (=Opheodrys) vernalis (smooth green snake). Herpetol. Rev. 27(3):154. Mara, W.P. 1996. Green Snakes. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications, 1996.

Mara, W.P. 1996. Green Snakes. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications, 1996. Minear, J. 1986. The nesting habits of the smooth green snake. Redstart 53(3): 113.

Minear, J. 1986. The nesting habits of the smooth green snake. Redstart 53(3): 113. Oldham, J.C. and H.M. Smith. 1987. Taxonomic significance of the intrinsic integumentary muscles of Opheodrys. Journal of the Colorado-Wyoming Academy of Science 19(1): 18.

Oldham, J.C. and H.M. Smith. 1987. Taxonomic significance of the intrinsic integumentary muscles of Opheodrys. Journal of the Colorado-Wyoming Academy of Science 19(1): 18. Pilliod, D.S. and T.C. Esque. 2023. Amphibians and reptiles. pp. 861-895. In: L.B. McNew, D.K. Dahlgren, and J.L. Beck (eds). Rangeland wildlife ecology and conservation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. 1023 p.

Pilliod, D.S. and T.C. Esque. 2023. Amphibians and reptiles. pp. 861-895. In: L.B. McNew, D.K. Dahlgren, and J.L. Beck (eds). Rangeland wildlife ecology and conservation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. 1023 p. Radaj, R.H. 1981. Opheodrys v. vernalis (smooth green snake). Reproduction. Herpetological Review 12: 80.

Radaj, R.H. 1981. Opheodrys v. vernalis (smooth green snake). Reproduction. Herpetological Review 12: 80. Redmer, M. 1987. Notes on the eggs and hatchlings of the smooth green snake, Opheodrys vernalis, in Dupage County, Illinois. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 22(9): 149.

Redmer, M. 1987. Notes on the eggs and hatchlings of the smooth green snake, Opheodrys vernalis, in Dupage County, Illinois. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 22(9): 149. Reichel, J. and D. Flath. 1995. Identification of Montana's amphibians and reptiles. Montana Outdoors 26(3):15-34.

Reichel, J. and D. Flath. 1995. Identification of Montana's amphibians and reptiles. Montana Outdoors 26(3):15-34. Robins, C.R. 1952. Variation in the greensnake, Opheodrys vernalis, from the Black Hills, South Dakota. Copeia 1952(3): 191-192.

Robins, C.R. 1952. Variation in the greensnake, Opheodrys vernalis, from the Black Hills, South Dakota. Copeia 1952(3): 191-192. Rundquist, E.M. 1979. The status of Bufo debilis and Opheodrys vernalis in Kansas. Transaction of the Kansas Academy of Science 82(1): 67-70.

Rundquist, E.M. 1979. The status of Bufo debilis and Opheodrys vernalis in Kansas. Transaction of the Kansas Academy of Science 82(1): 67-70. Schlauch, F.C. 1975. Agonistic behavior in a suburban Long Island population of the smooth green snake, Opheodrys vernalis. Engelhardtia 6(2): 25-26.

Schlauch, F.C. 1975. Agonistic behavior in a suburban Long Island population of the smooth green snake, Opheodrys vernalis. Engelhardtia 6(2): 25-26. Schmidt, K.P. and W.L. Necker. 1936. The scientific name of the American smooth green snake. Herpetologica 1: 63-64.

Schmidt, K.P. and W.L. Necker. 1936. The scientific name of the American smooth green snake. Herpetologica 1: 63-64. Smith, H.M. and D. Thompson. 1993. Four reptiles newly recorded from Ouray County, Colorado. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 28(4): 78-79.

Smith, H.M. and D. Thompson. 1993. Four reptiles newly recorded from Ouray County, Colorado. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 28(4): 78-79. Stebbins, R.C. 1985. A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 336 pp.

Stebbins, R.C. 1985. A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 336 pp. Stille, W.T. 1954. Observations on the reproduction and distribution of the green snake, Opheodrys vernalis (Harlan) Chicago Academy of Science Natural History Miscellaneous 127: 1-11.

Stille, W.T. 1954. Observations on the reproduction and distribution of the green snake, Opheodrys vernalis (Harlan) Chicago Academy of Science Natural History Miscellaneous 127: 1-11. Stuart, J.N. 2002. Liochlorophis (Opheodrys) vernalis (Smooth Green Snake). Reproduction. Herpetological Review 33(2):140-141.

Stuart, J.N. 2002. Liochlorophis (Opheodrys) vernalis (Smooth Green Snake). Reproduction. Herpetological Review 33(2):140-141. Stuart, J.N. and C.W. Painter. 1993. Notes on hibernation of the smooth green snake Opheodrys vernalis, in New Mexico. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 29(3): 140-142.

Stuart, J.N. and C.W. Painter. 1993. Notes on hibernation of the smooth green snake Opheodrys vernalis, in New Mexico. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 29(3): 140-142. Stuart, J.N. and W.G. Degenhardt. 1990. Opheodrys vernalis blanchardi (western smooth green snake). Herpetological Review 21(1): 23.

Stuart, J.N. and W.G. Degenhardt. 1990. Opheodrys vernalis blanchardi (western smooth green snake). Herpetological Review 21(1): 23. Walley, H.D. 2003. Liochlorophis, L. vernalis. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 776: 1-13.

Walley, H.D. 2003. Liochlorophis, L. vernalis. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 776: 1-13. Waters, R.M. 1993. Seasonal prey preference by the smooth green snake. M.S. Thesis, Central Michigan University; 54p. 1993.

Waters, R.M. 1993. Seasonal prey preference by the smooth green snake. M.S. Thesis, Central Michigan University; 54p. 1993. Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1966. The amphibians and reptiles of North Dakota. University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND. 104 pp.

Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1966. The amphibians and reptiles of North Dakota. University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND. 104 pp. Worthington, R.D. 1973. Remarks on the distribution of the smooth green snake, Opheodrys vernalis Blanchardi grobman in Texas. Southwest Natuealist 18(3): 344-346.

Worthington, R.D. 1973. Remarks on the distribution of the smooth green snake, Opheodrys vernalis Blanchardi grobman in Texas. Southwest Natuealist 18(3): 344-346.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Smooth Greensnake"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Reptiles"