View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Painted Turtle - Chrysemys picta

Native Species

Global Rank:

G5

State Rank:

S5

(see State Rank Reason below)

Agency Status

USFWS:

USFS:

BLM:

External Links

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is relatively common within suitable habitat and widely distributed across portions of the state.

General Description

EGGS:

Eggs of the Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta) are white, smooth, and oval. They are approximately 31 mm (1.2 in) long. Initially flexible, the shell gradually becomes firmer as water is absorbed (Ernst et al. 1994, Werner et al. 2004). Clutch size can range from 6-21 leathery eggs (Ernst et al. 1994, Russell and Bauer 2000). In southern Canada, clutch size is 20 and in Wisconsin and Minnesota, clutch size was documented as 10 (Christiansen and Moll 1973). In Wisconsin, 50% of females laid two clutches and nested from June to mid-July. Eggs may overwinter (Ernst 1972).

HATCHLINGS:

Hatchlings have a keeled carapace and vivid orange plastron (Hammerson 1999).

JUVENILES AND ADULTS:

Painted Turtles are named for their highly decorative yellow or reddish orange markings on its carapace and yellow markings on its legs, tail, and head. The plastron (underside) is a brilliant yellow or reddish orange with a large olive, loosely symmetrical blotch in the center, while the carapace (top) is mainly olive to black with more distinct yellow or reddish orange markings along its outer edge. Striking yellow lines along the head and neck, and a red spot behind the eye are distinctive for this species. Yellow markings on the fore and hind legs and tail are also present, but less obvious than those on the head. Brighter than adults, juveniles are otherwise similar in coloration. Adult females are larger than males; carapace length can vary from 8-18 cm (3.2 to 7.1 inches) (Werner et al. 2004). Mature males have a flat plastron, long forefeet claws, and rear vent located beyond the edge of the carapace, while the claws on the forefeet of the female are relatively short with the vent located at or inside the rear edge of the carapace (Hammerson 1999). Juveniles are distinguishable by a deep crease in the abdominal plastron shields (Hammerson 1999).

Diagnostic Characteristics

Lacking the distinct bright coloration, it is unlikely other turtle species in the state would be confused with the Painted Turtle. The Spiny Softshell (

Apalone spinifera) is smooth and creamy light brown in coloration with a relatively pointed head and flat pancake-like appearance. The Snapping Turtle (

Chelydra serpentina) has a dark brown, grey, or black carapace without contrasting coloration patterns anywhere on the shell or body. The Spiny Softshell is found in the central and eastern portions of the state, along the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers and their main tributaries, while the Snapping Turtle is limited to the central and southern portions of eastern Montana (Werner et al. 2004) with non-native populations located west of the Continental Divide (MTNHP POD 2022).

Species Range

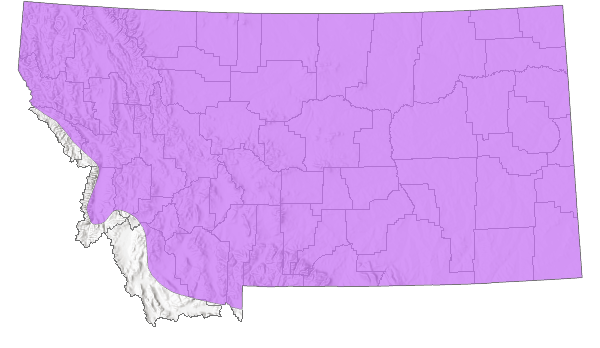

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Western Hemisphere Range

Range Comments

The Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta belli) in Montana is one of four subspecies of C. picta whose range extends across much of North America and southern Canada. This subspecies is found in the western U.S. and Canadian provinces. In Montana, the Painted Turtle is found throughout the state at lower elevations, with only a few counties in the central portion of the state lacking documented observations (Werner et al. 2004). The Eastern Painted Turtle (C. p. picta) is generally found in southeastern Canada, the northeastern U.S. and into southeastern U.S.; the Midland Painted Turtle (C. p. marginata) is documented in a few mid-western states. The Southern Painted Turtle (C. p. dorsalis) is generally located in the southcentral and southeastern U.S. states (NatureServe 2006). Chrysemys dorsalis (C. p. dorsalis) has been recognized as a distinct species from C. picta by Starkey et al. (2003) based upon molecular data. Disagreements on this point because of apparent intergrades in western Kentucky, southern Illinois, and southeastern Missouri leave the debate open if C. dorsalis is indeed conspecific with C. picta (NatureServe 2006).

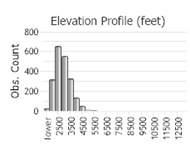

Maximum elevation: 1,993 m (6,539 ft) Duck Creek Bay of Hebgen Reservoir in Gallatin County (Clint Sestrich, Adam Kehoe, and Kyle Salzman, MTNHP POD 2022).

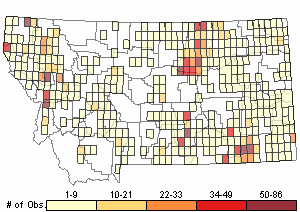

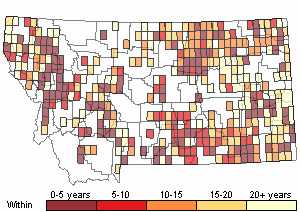

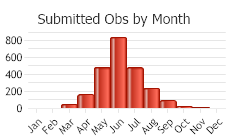

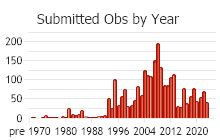

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 2805

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

An animal of aquatic environments, the Painted Turtle prefers slow-moving shallow waterways (streams, marshes, ponds, lakes, and creeks) with soft mud bottoms and aquatic vegetation. They have been documented in glacial lakes (Franz 1971); but not found in oligotropic mountain lakes above 1,025 m (3363 ft) in Mission Mountains (Brunson and Demaree 1951). Partially submerged logs and rocks for basking are desirable habitat features. This turtle species may colonize areas only seasonally wet but must return to permanent waters for winter hibernation. Behaviorally, juveniles and hatchlings may differ from mature individuals in habitat use. For example, in Michigan, Congdon et al. (1992) found that the hatchlings and juveniles were found in more shallow areas of marsh habitat. This behavior could result from greater food resources available or an attempt to avoid the larger predators present in deeper water (Hammerson 1999). Painted Turtles hibernate in mud at the bottom from early October to mid- or late April. Nests are placed in terrestrial habitats and may range up to 600 meters from water, where the eggs are left to incubate on their own (Ernst et al. 1994, Hammerson 1999)). In southern Canada, nest have been found on south-facing grassy slopes (MacCracken et al. 1983). In small marsh systems, the home range size may be very small (e.g., average of 1.2 ha in Michigan) (Rowe 2003), whereas in rivers, individual home range sizes are generally much larger (e.g., 7-26 km or 4.3-16.2 mi) (MacCulloch and Secoy 1983, NatureServe 2006).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Forest and Woodland

Deciduous Forest and Woodland

Wetland and Riparian

Alkaline - Saline Wetlands

Alpine Riparian and Wetland

Peatland

Riparian and Wetland Forest

Riparian Shrubland

Wet Meadow and Marsh

Food Habits

Ease of capture and size are major influences on what prey is taken. Food quality (animal vs. plant) and quantity may influence reproductive potential (MacCracken et al. 1983). Plant material was a significant food item (21 to 61%) in some Painted Turtles that had stopped growing. In addition to living and dead plants, Painted Turtles may consume a wide variety of living or dead organisms. In southern Saskatchewan, Painted Turtles preferred animal food (over 87% by volume) over abundant vegetation. Food interests include worms, leeches, insect larvae, pupae, and adults, as well as beetles, damselflies, dragonflies, water striders, water mites, spiders, mayflies, springtails, mosquitoes, crustaceans, snails, clams, frogs, and fish (Ernst et al. 1994, Hammerson 1999).

Ecology

Most nesting occurs during the afternoon hours, with a smaller proportion of nests initiated in the morning (Ernst et al. 1994). Nesting may occur early or late into the summer. Nests that hatch later in the breeding season may exhibit delayed emergence, e.g., the young overwinter in the nest. Even though Brettenbach et al. (1984) found greater survivorship of nests in Michigan if covered by a beneficial layer of snow, substantial mortality of overwintering hatchlings can occur (Nagle et al. 2000). Nest mortality (resulting from predation) can be high, especially for those nests placed closer, rather than farther, from a water source (Christens and Bider 1987). In Christens and Bider’s (1987) study, hatchlings overwintering in the nest survived early predation, suggesting that open nests may trigger olfactory clues and make early predation more likely.

Adult mortality can occur for individuals overwintering in areas prone to both drought and widely ranging winter temperatures. Christiansen and Bickham (1989) discovered more than 100 painted turtles frozen to death when the pond in which they were hibernating had frozen to the bottom. A 1995 mortality study (Fowle 1996) reported most Painted Turtles found dead on road occurred from late May to mid-July and consisted of 43% adult males, 26% adult females, and 31% of unknown sex, including juveniles. Densities of adult Painted Turtles were positively correlated with pond distance from the highway, and proportionally more juveniles and fewer adults were found at ponds closest to the highway, implying that roadkill mortality may be killing proportionally more adults (Fowle 1996).

Reproductive Characteristics

Sexual maturity appears more a consequence of size in males. Maturity occurs when plastron lengths are 70-95 mm (2.76-3.74 in), rather than age, and enhanced growth can shorten the average age of maturity of four years to two (Ernst et al. 1994). Females generally mature at 6-10 years of age at which time their plastron length ranges from 97-128 mm (3.8-5.1 in) (Ernst et al. 1994). Painted Turtles become active in late March or early April and may be observed basking on sun exposed banks, rocks, or logs in ponds, lakes, reservoirs, and streams. Nesting generally occurs from May until mid-July, with most nesting activity in June and early July. Christens and Bider (1987) found a consistent correlation between the mean temperature of the previous year for the current year’s nest initiation date for nests in Quebec, Canada. The flask-shaped nests are dug with the hind feet into rain-soaked soil, or soil sometimes softened with bladder water during digging (Ernst et al. 1994). Nests are dug into sandy, loamy, or other friable soil (Russell and Bauer 2000). Nest digging and egg laying can take up to four hours (Ernst et al. 1994), after which the eggs are covered over with soil. Poor weather conditions, such as extreme heat or drought can delay nesting (Lindeman 1989, Ernst et al. 1994).

Nest placement and the associated microsite characteristics are important as the sex of the incubating eggs is determined by temperature (cooler temperatures produce males, warmer produce females). While females may lay up to three clutches of eggs in one breeding season, Iverson and Smith (1993) reported an unusual 4 clutches for two females. Tinkle et al. (1981) estimated that 30-50% of females may not reproduce every year. Egg size and clutch size increase with female body size (Hammerson 1999).

A 1995 study from the Mission Valley in Montana (Fowle 1996) reported gravid females ranging from 7 to 17 in age, with smallest gravid female plastron lengths/widths of 166 and 82 mm (6.5 and 3.2 in) for 11- and 9-year old, respectively. The youngest males with secondary sex characteristics were 2 years old, with minimum plastron lengths/widths of 33 and 49 mm (1.3 and 1.9) for 4- and 3-year old, respectively (Fowle 1996).

Management

The following was taken from the Status and Conservation section for the Painted Turtle account in

Maxell et al. 2009.

The Painted Turtle is the most abundant turtle species in Montana; both the Spiny Softshell and Snapping Turtle have much smaller ranges, fewer recorded observations, and are more likely to be collected for harvest (Maxell and Hokit 1999, Werner et al. 2004). At the time when the comprehensive summaries of amphibians and reptiles in Montana (Maxell et al. 2003, Werner et al. 2004) were published, the Painted Turtle was documented in 41 counties, and broadly distributed across both the western and eastern portions of the state. Counties absent of records are generally located in the central portion of the state. State records are comprised of 392 observations in 40 counties, with 60 museum voucher records from 19 counties. The distribution of this species reflects its relative abundance compared to the two other turtle species in Montana. Specific state status information on the Painted Turtle is not available for Montana. Global trends over the short term are identified as stable, and relatively stable over the long term (NatureServe 2006).

Studies identifying or addressing specific risk factors for

Chrysemys picta in Montana are lacking; however, documented studies and other issues pertaining to their conservation include the following: (1) During the breeding season, females are quite sensitive to disturbance while on nesting forays; human activity (e.g., fishing) can disrupt nesting activity even from a distance (Hammerson 1999). (2) Artificially high mammalian predator numbers resulting from human augmented food resources can result in lower abundance of local turtle populations. While the Raccoon (

Procyon lotor) is the most detrimental native predator in all life stages of this turtle species (Ross 1988, Ernst et al. 1994), other native predators of Painted Turtle nests include the Thirteen-lined Ground Squirrel (

Ictidomys tridecemlineatus), Chipmunk (

Neotamias), Squirrel (

Sciurus), Striped Skunk (

Mephitis mephitis), American Badger (

Taxidea taxus), Coyote (

Canis latrans), Red Fox (

Vulpes vulpes), Common Raven (

Corvus corax), Plains Garter Snake (

Thamnophis radix), and other snakes (

Coluber). Hatchlings and small juveniles may fall prey to Giant Water Bugs (

Belostomatidae), Hammerson 1999). Young Painted Turtles are under threat of predation by Muskrats (

Ondatra zibethicus), American Mink (

Neogale vison), Raccoon, Snapping Turtles (

Chelydra serpentina), snakes (

Coluber), American Bullfrog (

Lithobates catesbeianus), large fish (

Micropterus,

Ictalurus), herons (

Ardea), and Giant Water Bugs (

Hemiptera) (Ernst et al. 1994, Maxell and Hokit 1999). In addition to Raccoons, adult Painted Turtles may be preyed upon by Bald Eagles (

Haliaeetus leucocephalus), Osprey (

Pandion haliaetus), and hawks. (3) Fowle’s (1996) mortality study in Montana reported most Painted Turtles found dead on the road occurring from late May to mid-July consisted of 43% adult males, 26% adult females, and 31% of unknown sex, including juveniles. Densities of adult turtles were positively correlated with pond distance from the highway, and proportionally more juveniles and fewer adults were found at ponds closest to the highway, implying that roadkill mortality may be killing proportionally more adults (Fowle 1996). (4) Ernst (1999) notes that, notwithstanding all of the potential wild predators, the greatest source of mortality for Painted Turtles is probably human caused: road kills, habitat destruction, pet trade, indiscriminate shooting and pesticide poisoning.

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Brettenbach, G.L., J.D. Congdon, and R.C. Van Loben Sels. 1984. Winter temperatures of Chrysemys picta nests in Michigan: effects on hatchling survival. Herpetologica 40(1): 76-81.

Brettenbach, G.L., J.D. Congdon, and R.C. Van Loben Sels. 1984. Winter temperatures of Chrysemys picta nests in Michigan: effects on hatchling survival. Herpetologica 40(1): 76-81. Brunson, R.B. and H.A. Demaree, Jr. 1951. The herpetology of the Mission Mountains, Montana. Copeia (4):306-308.

Brunson, R.B. and H.A. Demaree, Jr. 1951. The herpetology of the Mission Mountains, Montana. Copeia (4):306-308. Christens, E. and J.P. Bider. 1987. Nesting activity and hatching success of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata) in southwestern Quebec. Herpetologica 43(1): 55-65.

Christens, E. and J.P. Bider. 1987. Nesting activity and hatching success of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata) in southwestern Quebec. Herpetologica 43(1): 55-65. Christiansen, J.L. and E.O. Moll. 1973. Latitudinal reproductive variation within a single subspecies of painted turtle, Chrysemys picta bellii. Herpetologica 29(2):152-163.

Christiansen, J.L. and E.O. Moll. 1973. Latitudinal reproductive variation within a single subspecies of painted turtle, Chrysemys picta bellii. Herpetologica 29(2):152-163. Christiansen, J.L. and J.W. Bickham. 1989. Possible historic effects of pond drying and winterkill on the behavior of Kinosternon flavescens and Chrysemys picta. Journal of Herpetology 23(1): 91-94.

Christiansen, J.L. and J.W. Bickham. 1989. Possible historic effects of pond drying and winterkill on the behavior of Kinosternon flavescens and Chrysemys picta. Journal of Herpetology 23(1): 91-94. Congdon, J.D., S.W. Gotte, S.W., and R.W. Mcdiarmid. 1992. Ontogenetic changes in habitat use by juvenile turtles, Chelydra serpentina and Chrysemys picta. Canadian Field Naturalist 106(2): 241-248.

Congdon, J.D., S.W. Gotte, S.W., and R.W. Mcdiarmid. 1992. Ontogenetic changes in habitat use by juvenile turtles, Chelydra serpentina and Chrysemys picta. Canadian Field Naturalist 106(2): 241-248. Ernst, C. H., R. W. Barbour, and J. E. Lovich. 1994. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D.C. 578 p.

Ernst, C. H., R. W. Barbour, and J. E. Lovich. 1994. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D.C. 578 p. Ernst, C.H. 1972. Temperature-activity relationship in the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta. Copeia 1972(2): 217-222.

Ernst, C.H. 1972. Temperature-activity relationship in the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta. Copeia 1972(2): 217-222. Fowle S.C. 1996. Effects of roadkill mortality on the western painted turtle (Chrysemys picta bellii) in the Mission Valley, western Montana. pp. 205-223. In: Evink G., D. Ziegler, P. Garrett, and J. Berry (eds). Highways and movement of wildlife: improving habitat connections and wildlife passageways across highway corridors. Proceedings of the Florida Department of Transportation/Federal Highway Administration Transportation-Related Wildlife Mortality Seminar. April 30-May 2, 1996. Orlando, Florida.

Fowle S.C. 1996. Effects of roadkill mortality on the western painted turtle (Chrysemys picta bellii) in the Mission Valley, western Montana. pp. 205-223. In: Evink G., D. Ziegler, P. Garrett, and J. Berry (eds). Highways and movement of wildlife: improving habitat connections and wildlife passageways across highway corridors. Proceedings of the Florida Department of Transportation/Federal Highway Administration Transportation-Related Wildlife Mortality Seminar. April 30-May 2, 1996. Orlando, Florida. Franz, R. 1971. Notes on the distribution and ecology of the herpetofauna of northwestern Montana. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 7: 1-10.

Franz, R. 1971. Notes on the distribution and ecology of the herpetofauna of northwestern Montana. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 7: 1-10. Hammerson, G.A. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. University Press of Colorado & Colorado Division of Wildlife. Denver, CO. 484 p.

Hammerson, G.A. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. University Press of Colorado & Colorado Division of Wildlife. Denver, CO. 484 p. Iverson, J.B. and G.R. Smith. 1993. Reproductive ecology of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) in the Nebraska Sandhills and across its range. Copeia 1993(1): 1-21.

Iverson, J.B. and G.R. Smith. 1993. Reproductive ecology of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) in the Nebraska Sandhills and across its range. Copeia 1993(1): 1-21. Lindeman, P.V. 1989. Chrysemys picta belli (western painted turtle). Egg retention. Herpetological Review 20(3): 69.

Lindeman, P.V. 1989. Chrysemys picta belli (western painted turtle). Egg retention. Herpetological Review 20(3): 69. MacCracken, J.G., L.E. Alexander, and D.W. Uresk. 1983. An important lichen of southeastern Montana rangelands. Journal of Range Management 36(1):35-37.

MacCracken, J.G., L.E. Alexander, and D.W. Uresk. 1983. An important lichen of southeastern Montana rangelands. Journal of Range Management 36(1):35-37. Maxell, B.A. and D.G. Hokit. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles. Pages 2.1– 2.30 In G. Joslin and H. Youmans, committee chairs. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a compendium of the current state of understanding in Montana. Committee on Effects of Recreation on Wildlife, Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Maxell, B.A. and D.G. Hokit. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles. Pages 2.1– 2.30 In G. Joslin and H. Youmans, committee chairs. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a compendium of the current state of understanding in Montana. Committee on Effects of Recreation on Wildlife, Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. Maxell, B.A., J.K. Werner, P. Hendricks, and D.L. Flath. 2003. Herpetology in Montana: a history, status summary, checklists, dichotomous keys, accounts for native, potentially native, and exotic species, and indexed bibliography. Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology, Northwest Fauna Number 5. Olympia, WA. 135 p.

Maxell, B.A., J.K. Werner, P. Hendricks, and D.L. Flath. 2003. Herpetology in Montana: a history, status summary, checklists, dichotomous keys, accounts for native, potentially native, and exotic species, and indexed bibliography. Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology, Northwest Fauna Number 5. Olympia, WA. 135 p. Maxell, B.A., P. Hendricks, M.T. Gates, and S. Lenard. 2009. Montana amphibian and reptile status assessment, literature review, and conservation plan, June 2009. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 643 p.

Maxell, B.A., P. Hendricks, M.T. Gates, and S. Lenard. 2009. Montana amphibian and reptile status assessment, literature review, and conservation plan, June 2009. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 643 p. Nagle, R.D., O.M. Kinney, J.D. Congdon, and C.W. Beck. 2000. Winter survivorship of hatching painted turtles (Chrysemys picta) in Michigan. Canadian Journal of Zoology 78(2): 226-233.

Nagle, R.D., O.M. Kinney, J.D. Congdon, and C.W. Beck. 2000. Winter survivorship of hatching painted turtles (Chrysemys picta) in Michigan. Canadian Journal of Zoology 78(2): 226-233. Ross, D.A. 1988. Chrysemys picta (painted turtle). Predation. Herpetological Review 19(4): 85-87, illustr.

Ross, D.A. 1988. Chrysemys picta (painted turtle). Predation. Herpetological Review 19(4): 85-87, illustr. Rowe, J.W. 2003. Activity and movements of midland painted turtles (Chrysemys picta marginata) living in a small marsh system on Beaver Island, Michigan. Journal of Herpetology 37: 342-353.

Rowe, J.W. 2003. Activity and movements of midland painted turtles (Chrysemys picta marginata) living in a small marsh system on Beaver Island, Michigan. Journal of Herpetology 37: 342-353. Russell, A. P. and A. M. Bauer. 2000. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Alberta: A field guide and primer of boreal herpetology. University of Calgary Press, Toronto, Ontario. 279 p.

Russell, A. P. and A. M. Bauer. 2000. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Alberta: A field guide and primer of boreal herpetology. University of Calgary Press, Toronto, Ontario. 279 p. Starkey, D. E., H. B. Shaffer, R. L. Burke, M.R.J. Forstner, J. B. Iverson, F. J. Janzen, A.G.J. Rhodin, and G. R. Ultsch. 2003. Molecular systematics, phylogeography, and the effects of Pleistocene glaciation in the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) complex. Evolution 57(1): 119-128.

Starkey, D. E., H. B. Shaffer, R. L. Burke, M.R.J. Forstner, J. B. Iverson, F. J. Janzen, A.G.J. Rhodin, and G. R. Ultsch. 2003. Molecular systematics, phylogeography, and the effects of Pleistocene glaciation in the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) complex. Evolution 57(1): 119-128. Tinkle, D.W., J.D. Congdon, and P.C. Rosen. 1981. Nesting frequency and success: implications for the demography of painted turtles. Ecology 62: 1426-1432.

Tinkle, D.W., J.D. Congdon, and P.C. Rosen. 1981. Nesting frequency and success: implications for the demography of painted turtles. Ecology 62: 1426-1432. Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks and D.L. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and Reptiles of Montana. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, MT. 262 pp.

Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks and D.L. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and Reptiles of Montana. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, MT. 262 pp.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? [DCC] Decker Coal Company. 1998. 1997 Consolidated annual progress report. Decker Coal Company West, North and East Pits. Decker, MT.

[DCC] Decker Coal Company. 1998. 1997 Consolidated annual progress report. Decker Coal Company West, North and East Pits. Decker, MT. [EI] Econ Incorporated. 1984. Terrestrial wildlife inventory for the Lame Jones and Ismay coal lease tracts. Econ Incorporated. Helena, MT.

[EI] Econ Incorporated. 1984. Terrestrial wildlife inventory for the Lame Jones and Ismay coal lease tracts. Econ Incorporated. Helena, MT. [OEA] Olson Elliot and Associates Research. 1985. 1983-1984 Wildlife monitoring report for the CX Ranch project. Olson Elliot and Associates Research. Helena, MT.

[OEA] Olson Elliot and Associates Research. 1985. 1983-1984 Wildlife monitoring report for the CX Ranch project. Olson Elliot and Associates Research. Helena, MT. [PRESI] Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. 1998a. Big Sky Mine 1997 wildlife monitoring studies. Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. Gillete, WY.

[PRESI] Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. 1998a. Big Sky Mine 1997 wildlife monitoring studies. Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. Gillete, WY. [PRESI] Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. 1998b. Spring Creek Mine 1997 wildlife monitoring studies. Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. Gillete, WY.

[PRESI] Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. 1998b. Spring Creek Mine 1997 wildlife monitoring studies. Powder River Eagle Studies Incorporated. Gillete, WY. [VTNWI] VTN Wyoming Incorporated. No Date. Second year's analysis of terrestrial wildlife on proposed mine access and railroad routes in southern Montana and northern Wyoming, March 1979 - February 1980. VTN Wyoming Incorporated. Sheridan, WY. 62 p.

[VTNWI] VTN Wyoming Incorporated. No Date. Second year's analysis of terrestrial wildlife on proposed mine access and railroad routes in southern Montana and northern Wyoming, March 1979 - February 1980. VTN Wyoming Incorporated. Sheridan, WY. 62 p. [WESCO] Western Ecological Services Company. 1983a. Wildlife inventory of the Knowlton known recoverable coal resource area, Montana. Western Ecological Services Company, Novato, CA. 107 p.

[WESCO] Western Ecological Services Company. 1983a. Wildlife inventory of the Knowlton known recoverable coal resource area, Montana. Western Ecological Services Company, Novato, CA. 107 p. [WESCO] Western Ecological Services Company. 1983b. Wildlife inventory of the Southwest Circle known recoverable coal resource area, Montana. Western Ecological Services Company, Novato, CA. 131 p.

[WESCO] Western Ecological Services Company. 1983b. Wildlife inventory of the Southwest Circle known recoverable coal resource area, Montana. Western Ecological Services Company, Novato, CA. 131 p. [WESTECH] Western Technology and Engineering Incorporated. 1998. Wildlife Monitoring Absaloka Mine Area 1997. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc., Helena, Mt.

[WESTECH] Western Technology and Engineering Incorporated. 1998. Wildlife Monitoring Absaloka Mine Area 1997. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc., Helena, Mt. [WWPC] Washington Water Power Company. 1995. 1994 wildlife report Noxon Rapids and Cabinet Gorge Reservoirs. Washington Water Power Company. Spokane, WA.

[WWPC] Washington Water Power Company. 1995. 1994 wildlife report Noxon Rapids and Cabinet Gorge Reservoirs. Washington Water Power Company. Spokane, WA. Ackerman, R.A., R.C. Seagrave, R. Dmi’el, and A. Ar. 1985. Water and heat exchange between parchment-shelled reptile eggs and their surroundings. Copeia 1985(3): 703-711.

Ackerman, R.A., R.C. Seagrave, R. Dmi’el, and A. Ar. 1985. Water and heat exchange between parchment-shelled reptile eggs and their surroundings. Copeia 1985(3): 703-711. Almeida, V.M.F., L.T. Buck, and P.W. Hochachka. 1994. Substrate and acute temperature effects on turtle heart and liver mitochondria. American Journal of Physiology 266(3 PART 2): R858-R862.

Almeida, V.M.F., L.T. Buck, and P.W. Hochachka. 1994. Substrate and acute temperature effects on turtle heart and liver mitochondria. American Journal of Physiology 266(3 PART 2): R858-R862. Anderson, C. W. and J. Keifer. 1996. Extraretinal photoreceptors in the caudal mesencephalon of the turtle, Chrysemys picta. American Zoology 36(5): 74A.

Anderson, C. W. and J. Keifer. 1996. Extraretinal photoreceptors in the caudal mesencephalon of the turtle, Chrysemys picta. American Zoology 36(5): 74A. Anderson, M.E. 1977. Aspects of the ecology of two sympatric species of Thamnophis and heavy metal accumulation with the species. M.S. thesis, University of Montana, Missoula. 147 pp.

Anderson, M.E. 1977. Aspects of the ecology of two sympatric species of Thamnophis and heavy metal accumulation with the species. M.S. thesis, University of Montana, Missoula. 147 pp. Anderson, P.K. 1958. The photic responses and water-approach behavior of hatchling turtles. Copeia 1958: 211-215.

Anderson, P.K. 1958. The photic responses and water-approach behavior of hatchling turtles. Copeia 1958: 211-215. Andrews, K.D. 1996. An endochondral rather than a dermal origin for scleral ossicles in cryptodiran turtles. Journal of Herpetology 30(2): 257-260.

Andrews, K.D. 1996. An endochondral rather than a dermal origin for scleral ossicles in cryptodiran turtles. Journal of Herpetology 30(2): 257-260. Ashe, V.M., D. Chiszar, and H.M. Smith. 1975. Behavior of aquatic and terrestrial turtles on a visual cliff. Chelonia 2(4): 3-7.

Ashe, V.M., D. Chiszar, and H.M. Smith. 1975. Behavior of aquatic and terrestrial turtles on a visual cliff. Chelonia 2(4): 3-7. Atkinson, E.C. and M.L. Atkinson. 2004. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Ashland and Sioux of the Custer National Forest with special emphasis on the Three-Mile Stewardship Area:2002. Marmot's Edge Conservation. 22 p.

Atkinson, E.C. and M.L. Atkinson. 2004. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Ashland and Sioux of the Custer National Forest with special emphasis on the Three-Mile Stewardship Area:2002. Marmot's Edge Conservation. 22 p. Attaway, M.B., G.C. Packard, and M.J. Packard. 1996. Hatchling painted turtles survive only brief freezing of body fluids. American Zoology 36(5): 34A.

Attaway, M.B., G.C. Packard, and M.J. Packard. 1996. Hatchling painted turtles survive only brief freezing of body fluids. American Zoology 36(5): 34A. Babcock, H.L. 1933. The eastern limit of range for Chrysemys picta marginata. Copeia 1933(2): 101.

Babcock, H.L. 1933. The eastern limit of range for Chrysemys picta marginata. Copeia 1933(2): 101. Baker, M.R. 1979. Serpinema/ spp. (Nematoda: camallanidae) from turtles of North America and Europe. Canadian Journal of Zoology 57(4): 934-939.

Baker, M.R. 1979. Serpinema/ spp. (Nematoda: camallanidae) from turtles of North America and Europe. Canadian Journal of Zoology 57(4): 934-939. Balcombe, J.P., and L.E. Licht. 1986. Some aspects of the ecology of the midland painted turtle, Chrysemys picta marginata, in Wye Marsh, Ontario (Canada). Canadian Field Naturalist 9(3): 98-100.

Balcombe, J.P., and L.E. Licht. 1986. Some aspects of the ecology of the midland painted turtle, Chrysemys picta marginata, in Wye Marsh, Ontario (Canada). Canadian Field Naturalist 9(3): 98-100. Baldwin, E.A., M.N. Marchand, and J.A. Litvaitis. 2004. Terrestrial habitat use by nesting painted turtles in landscapes with different levels of fragmentation. Northeastern Naturalist 11(1): 41-48.

Baldwin, E.A., M.N. Marchand, and J.A. Litvaitis. 2004. Terrestrial habitat use by nesting painted turtles in landscapes with different levels of fragmentation. Northeastern Naturalist 11(1): 41-48. Barone, M.C. and F.A. Jacques. 1975. The effects of induced cold torpor and time of year on blood coagulation in Pseudemys scripta elegans and. Chrysemys picta belli. Comparative Biochemistry Physiology A 50(4): 717-721.

Barone, M.C. and F.A. Jacques. 1975. The effects of induced cold torpor and time of year on blood coagulation in Pseudemys scripta elegans and. Chrysemys picta belli. Comparative Biochemistry Physiology A 50(4): 717-721. Bayless, L.E. 1975. Population parameters for Chrysemys picta in a New York pond. American Midland Naturalist 93(1):168-176.

Bayless, L.E. 1975. Population parameters for Chrysemys picta in a New York pond. American Midland Naturalist 93(1):168-176. Beall, R.J. and C.A. Privitera. 1973. Effects of cold exposure on cardiac metabolism of the turtle C. picta. American Journal of Physiology 224: 435-441.

Beall, R.J. and C.A. Privitera. 1973. Effects of cold exposure on cardiac metabolism of the turtle C. picta. American Journal of Physiology 224: 435-441. Beane, J.C. and K.E. Douglass. Chrysemys picta picta (Eastern Painted Turtle). Predation. Herpetological Review 36:310.

Beane, J.C. and K.E. Douglass. Chrysemys picta picta (Eastern Painted Turtle). Predation. Herpetological Review 36:310. Belmore, B. 1985. Early spring turtle observations in Massachusetts. Northern Ohio Association of the Herpetological Notes 12(7): 10.

Belmore, B. 1985. Early spring turtle observations in Massachusetts. Northern Ohio Association of the Herpetological Notes 12(7): 10. Benson, K.R. 1978. Herpetology of the Lewis and Clark expedition 1804-1806. Herpetological Review 9(3): 87-91.

Benson, K.R. 1978. Herpetology of the Lewis and Clark expedition 1804-1806. Herpetological Review 9(3): 87-91. Bider, J.R. and W. Hoeck. 1971. An efficient and apparently unbiased sampling technique for population studies of painted turtles. Herpetologica 27(4): 481-484.

Bider, J.R. and W. Hoeck. 1971. An efficient and apparently unbiased sampling technique for population studies of painted turtles. Herpetologica 27(4): 481-484. Birchard, G.F. and G.C. Packard. 1996. Heart rate during supercooling in hatchling turtles. American Zoology 36(5): 34A.

Birchard, G.F. and G.C. Packard. 1996. Heart rate during supercooling in hatchling turtles. American Zoology 36(5): 34A. Birchard, G.F. and G.C. Packard. 1997. Cardiac activity in supercooled hatchlings of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta). Journal of Herpetology 31(1): 166-169.

Birchard, G.F. and G.C. Packard. 1997. Cardiac activity in supercooled hatchlings of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta). Journal of Herpetology 31(1): 166-169. Bishop, S.C. and F.J.W. Schmidt. 1931. The painted turtles of the genus Chrysemys. Zool. Ser. Field. Mus. Nat. Hist. 18: 123-139.

Bishop, S.C. and F.J.W. Schmidt. 1931. The painted turtles of the genus Chrysemys. Zool. Ser. Field. Mus. Nat. Hist. 18: 123-139. Black, J.H. and A.H. Black. 1987. Western painted turtle in Grant County, Oregon. Great Basin Naturalist 47(2): 344.

Black, J.H. and A.H. Black. 1987. Western painted turtle in Grant County, Oregon. Great Basin Naturalist 47(2): 344. Black, J.H. and J.N. Black. 1971. Montana and its turtles. International Turtle and Tortoise Society 1971(May-July): 10-11, 34-35.

Black, J.H. and J.N. Black. 1971. Montana and its turtles. International Turtle and Tortoise Society 1971(May-July): 10-11, 34-35. Blau, A. and A.S. Powers. 1989. Discrimination learning in turtle after lesions of the dorsal cortex or basal forebrain. Psychobiology 17(4): 445-449.

Blau, A. and A.S. Powers. 1989. Discrimination learning in turtle after lesions of the dorsal cortex or basal forebrain. Psychobiology 17(4): 445-449. Bleakney, J.S. 1958. Postglacial dispersal of the turtle Chrysemys picta. Herpetologica 14: 101-104.

Bleakney, J.S. 1958. Postglacial dispersal of the turtle Chrysemys picta. Herpetologica 14: 101-104. BLM. 1982b. Moorhead baseline inventory - wildlife. Bureau of Land Management, Miles City District Office. Miles City, MT. 29 pp.

BLM. 1982b. Moorhead baseline inventory - wildlife. Bureau of Land Management, Miles City District Office. Miles City, MT. 29 pp. Boback, S., L. Shelley, C. Montgomery, and J. Hobert, E. Bergman, B. Hill, S.P. Mackessy. 1996. Chrysemys picta bellii (western painted turtle). Herpetological Review 27(4): 210.

Boback, S., L. Shelley, C. Montgomery, and J. Hobert, E. Bergman, B. Hill, S.P. Mackessy. 1996. Chrysemys picta bellii (western painted turtle). Herpetological Review 27(4): 210. Boundy, J. 1991. A possible native population of the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta, in Arizona. Bulletin of Chicago Herpetology Society 26(2):33.

Boundy, J. 1991. A possible native population of the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta, in Arizona. Bulletin of Chicago Herpetology Society 26(2):33. Boundy, J. 2001. Herpetofaunal surveys in the Clark Fork Valley region, Montana. Herpetological Natural History 8: 15-26.

Boundy, J. 2001. Herpetofaunal surveys in the Clark Fork Valley region, Montana. Herpetological Natural History 8: 15-26. Bowen, K.D. and F.J. Janzen. Rainfall and depredation of nests of the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta. Journal of Herpetology 39(4):649-652.

Bowen, K.D. and F.J. Janzen. Rainfall and depredation of nests of the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta. Journal of Herpetology 39(4):649-652. Bowen, K.D., R.J. Spencer, and F.J. Janzen. 2005. A comparative study of environmental factors that affect nesting in Australian and North American freshwater turtles. Journal of Zoology (London) 267(4):397-404.

Bowen, K.D., R.J. Spencer, and F.J. Janzen. 2005. A comparative study of environmental factors that affect nesting in Australian and North American freshwater turtles. Journal of Zoology (London) 267(4):397-404. Braid, M.R. 1974. A Bal-Chatri trap for basking turtles. Copeia 1974(2):539-540.

Braid, M.R. 1974. A Bal-Chatri trap for basking turtles. Copeia 1974(2):539-540. Bramblett, R.G., and A.V. Zale. 2002. Montana Prairie Riparian Native Species Report. Montana Cooperative Fishery Research Unit, Montana State University - Bozeman.

Bramblett, R.G., and A.V. Zale. 2002. Montana Prairie Riparian Native Species Report. Montana Cooperative Fishery Research Unit, Montana State University - Bozeman. Britson, C.A. and W.H.N. Gutzke. 1993. Antipredator mechanisms of hatchling freshwater turtles. Copeia 1993(2): 435-440.

Britson, C.A. and W.H.N. Gutzke. 1993. Antipredator mechanisms of hatchling freshwater turtles. Copeia 1993(2): 435-440. Brockelman, W.Y. 1975. Competition, the fitness of offspring, and optimal clutch size. American Naturalist 109: 677-699.

Brockelman, W.Y. 1975. Competition, the fitness of offspring, and optimal clutch size. American Naturalist 109: 677-699. Brooks, D.R. 1981. Raw similarity measures of shared parasites: an empirical tool for determining host phylogenetic relationships? Systems of Zoology 30(2): 203-207.

Brooks, D.R. 1981. Raw similarity measures of shared parasites: an empirical tool for determining host phylogenetic relationships? Systems of Zoology 30(2): 203-207. Brown, E.E. 1992. Notes on amphibians and reptiles of the western Piedmont of North Carolina. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 108(1): 38-54.

Brown, E.E. 1992. Notes on amphibians and reptiles of the western Piedmont of North Carolina. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 108(1): 38-54. Brunson, R.B. 1955. Check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 15: 27-29.

Brunson, R.B. 1955. Check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 15: 27-29. Buck, L.T. and P.E. Bickler. 1995. Role of adenosine in nmda receptor modulation in the cerebral cortex of an anoxia-tolerant turtle (Chrysemys picta belli). Journal of Experimental Biology 198(7): 1621-1628.

Buck, L.T. and P.E. Bickler. 1995. Role of adenosine in nmda receptor modulation in the cerebral cortex of an anoxia-tolerant turtle (Chrysemys picta belli). Journal of Experimental Biology 198(7): 1621-1628. Buck, L.T., P.W. Hochachka, A. Schoen, E. Gnaiger. 1993. Microcalorimetric measurement of reversible metabolic suppression induced by anoxia in isolated hepatocytes. American Journal of Physiology 265(5 PART 2): R1014-R1019.

Buck, L.T., P.W. Hochachka, A. Schoen, E. Gnaiger. 1993. Microcalorimetric measurement of reversible metabolic suppression induced by anoxia in isolated hepatocytes. American Journal of Physiology 265(5 PART 2): R1014-R1019. Buck, L.T., S.C. Land, S.C., and P.W. Hochachka. 1993. Anoxia-tolerant hepatocytes: Model system for study of reversible metabolic suppression. American Journal Of Physiology 265(1 Part 2): R49-R56.

Buck, L.T., S.C. Land, S.C., and P.W. Hochachka. 1993. Anoxia-tolerant hepatocytes: Model system for study of reversible metabolic suppression. American Journal Of Physiology 265(1 Part 2): R49-R56. Bureau of Indian Affairs, Department of the Interior. 1981. Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Unpublished report for the Crow/Shell Coal Lease, Crow Indian Reservation, Montana.

Bureau of Indian Affairs, Department of the Interior. 1981. Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Unpublished report for the Crow/Shell Coal Lease, Crow Indian Reservation, Montana. Burroughs, R. D. 1961. Natural history of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Michigan State University Press, East Lansing. 340 p.

Burroughs, R. D. 1961. Natural history of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Michigan State University Press, East Lansing. 340 p. Bury, R.B., J.H. Wolfheim, and R.A. Luckenbach. 1979. Agonistic behavior in free-living painted turtles (Chrysemys picta belli). Biological Behavior 1979: 227-239.

Bury, R.B., J.H. Wolfheim, and R.A. Luckenbach. 1979. Agonistic behavior in free-living painted turtles (Chrysemys picta belli). Biological Behavior 1979: 227-239. Butts, T.W. 1997. Mountain Inc. wildlife monitoring Bull Mountains Mine No. 1, 1996. Western Technology and Engineering. Helena, MT.

Butts, T.W. 1997. Mountain Inc. wildlife monitoring Bull Mountains Mine No. 1, 1996. Western Technology and Engineering. Helena, MT. Cagle, F.R. 1937. Egg laying habits of the slider turtle (Pseudemys troosti), the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) and the musk turtle (Sternotherus odoratus). Tennessee Academy of Science 12: 225-235.

Cagle, F.R. 1937. Egg laying habits of the slider turtle (Pseudemys troosti), the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) and the musk turtle (Sternotherus odoratus). Tennessee Academy of Science 12: 225-235. Cagle, F.R. 1942. Turtle populations in southern Illinois. Copeia 1942(3): 155-162.

Cagle, F.R. 1942. Turtle populations in southern Illinois. Copeia 1942(3): 155-162. Cagle, F.R. 1954. Observations on the life cycles of painted turtles (genus Chrysemys). American Midland Naturalist 52: 225-235.

Cagle, F.R. 1954. Observations on the life cycles of painted turtles (genus Chrysemys). American Midland Naturalist 52: 225-235. Cagle, K.D., G.C. Packard, K. Miller, and M.J. Packard. 1993. Effects of the microclimate in natural nests on development of embryonic painted turtles, Chrysemys picta. Functional Ecology 7(6): 653-660.

Cagle, K.D., G.C. Packard, K. Miller, and M.J. Packard. 1993. Effects of the microclimate in natural nests on development of embryonic painted turtles, Chrysemys picta. Functional Ecology 7(6): 653-660. Callard, I.P. and V. Abrams-Motz. 1985. Hormonal regulation of myometrial activity in the turtle, Chrysemys picta. American Zoology 25(4): 117A.

Callard, I.P. and V. Abrams-Motz. 1985. Hormonal regulation of myometrial activity in the turtle, Chrysemys picta. American Zoology 25(4): 117A. Callard, I.P., E.V. Callard, V. Lance, and S. Eccles. 1976. Seasonal changes in testicular structure and function and the effects of gonadotropins in the freshwater turtle, Chrysemys picta. General Comparative Endocrinology 30: 347-356.

Callard, I.P., E.V. Callard, V. Lance, and S. Eccles. 1976. Seasonal changes in testicular structure and function and the effects of gonadotropins in the freshwater turtle, Chrysemys picta. General Comparative Endocrinology 30: 347-356. Callard, I.P., V. Lance, A.R. Salhanick, and D. Barad. 1978. The annual ovarian cycle of /Chrysemys picta/: correlated changes in plasma steroids and parameters of Vitellogenesis. General Comparative Endocrinology 35(1): 245-257.

Callard, I.P., V. Lance, A.R. Salhanick, and D. Barad. 1978. The annual ovarian cycle of /Chrysemys picta/: correlated changes in plasma steroids and parameters of Vitellogenesis. General Comparative Endocrinology 35(1): 245-257. Cameron, J.N. 1989. The respiratory physiology of animals. Oxford University Press, New York.

Cameron, J.N. 1989. The respiratory physiology of animals. Oxford University Press, New York. Carey, M.G. and K.B. Aubry. 1988. Geographic distribution. Chrysemys picta belli (western painted turtle). Herpetological Review 19(3): 61.

Carey, M.G. and K.B. Aubry. 1988. Geographic distribution. Chrysemys picta belli (western painted turtle). Herpetological Review 19(3): 61. Carley, W.W. and I.P. Callard. 1980. Gonadotropin binding by ovarian tissues of the turtle Chrysemys picta. American Zoology 20(4): 792.

Carley, W.W. and I.P. Callard. 1980. Gonadotropin binding by ovarian tissues of the turtle Chrysemys picta. American Zoology 20(4): 792. Carlsen, T. and R. Northrup. 1992. Canyon Ferry Wildlife Management Area Final Draft Management Plan. March 1992.

Carlsen, T. and R. Northrup. 1992. Canyon Ferry Wildlife Management Area Final Draft Management Plan. March 1992. Case, D.J. and W.C. Scharf. 1985. Additions to the birds and land vertebrates of north Manitou Island. Jack-Pine Warber 63(1): 17-23.

Case, D.J. and W.C. Scharf. 1985. Additions to the birds and land vertebrates of north Manitou Island. Jack-Pine Warber 63(1): 17-23. Casper, G. 1987. New herpetological records for Wisconsin, USA. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 22(5): 95.

Casper, G. 1987. New herpetological records for Wisconsin, USA. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 22(5): 95. Chan, C.Y., J. Hounsgaard, and C. Nicholson. 1988. Effects of electric fields on transmembrane potential and excitability of turtle cerebellar Purkinje cells in vitro. Journal of Physiology (Cambridge) 402: 751-771.

Chan, C.Y., J. Hounsgaard, and C. Nicholson. 1988. Effects of electric fields on transmembrane potential and excitability of turtle cerebellar Purkinje cells in vitro. Journal of Physiology (Cambridge) 402: 751-771. Cheek, W.K. 1995. Population and biomass estimation of turtles at Spring Meadow State Park, Helena, Montana. Undergraduate Honors Thesis. Carroll College, Helena, MT. 29 p.

Cheek, W.K. 1995. Population and biomass estimation of turtles at Spring Meadow State Park, Helena, Montana. Undergraduate Honors Thesis. Carroll College, Helena, MT. 29 p. Chiszar, D. and H.M. Smith. 1992a. Chrysemys picta bellii (western painted turtle). Herpetological Review 23(4): 122.

Chiszar, D. and H.M. Smith. 1992a. Chrysemys picta bellii (western painted turtle). Herpetological Review 23(4): 122. Chiszar, D. and H.M. Smith. 1993a. Additions to the known herpetofauna of Banner County, Nebraska. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 28(6): 118-119.

Chiszar, D. and H.M. Smith. 1993a. Additions to the known herpetofauna of Banner County, Nebraska. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 28(6): 118-119. Chiszar, D. and H.M. Smith. 1993b. Chrysemys picta bellii (western painted turtle). Herpetological Review 24(4): 254. (154?)

Chiszar, D. and H.M. Smith. 1993b. Chrysemys picta bellii (western painted turtle). Herpetological Review 24(4): 254. (154?) Chiva, M., D. Kulak, and H.E. Kasinsky. 1989. Sperm basic proteins in the turtle Chrysemys picta: Characterization and evolutionary implications. Journal of Experimental Zoology 249(3): 329-333.

Chiva, M., D. Kulak, and H.E. Kasinsky. 1989. Sperm basic proteins in the turtle Chrysemys picta: Characterization and evolutionary implications. Journal of Experimental Zoology 249(3): 329-333. Christens, E. and J.P. Bider. 1986. Reproductive ecology of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata) in southwestern Quebec. Canadian Journal of Zoology 64: 914-920.

Christens, E. and J.P. Bider. 1986. Reproductive ecology of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata) in southwestern Quebec. Canadian Journal of Zoology 64: 914-920. Christiansen, J. 1986. North American reptiles. 1. Golden turtles (Chrysemys picta). Nordisk Herpetologisk Forening 29(2): 43-58.

Christiansen, J. 1986. North American reptiles. 1. Golden turtles (Chrysemys picta). Nordisk Herpetologisk Forening 29(2): 43-58. Christiansen, J.L. and J.M. Grzybowski, and B.P. Rinner. 2004. Facial lesions in turtles, observations on prevalence, reoccurence, and multiple origins. Journal of Herpetology 37(3):293-298.

Christiansen, J.L. and J.M. Grzybowski, and B.P. Rinner. 2004. Facial lesions in turtles, observations on prevalence, reoccurence, and multiple origins. Journal of Herpetology 37(3):293-298. Churchill, T.A. and K.B. Storey. 1991. Metabolic response to freezing by organs of hatchling painted turtles Chrysemys picta marginata and Chrysemys picta bellii. Canadian Journal of Zoology 69(12): 2978-2984.

Churchill, T.A. and K.B. Storey. 1991. Metabolic response to freezing by organs of hatchling painted turtles Chrysemys picta marginata and Chrysemys picta bellii. Canadian Journal of Zoology 69(12): 2978-2984. Churchill, T.A. and K.B. Storey. 1992b. Natural freeze tolerance in painted turtle hatchlings: a metabolic assessment. Cryobiology 29(6): 760.

Churchill, T.A. and K.B. Storey. 1992b. Natural freeze tolerance in painted turtle hatchlings: a metabolic assessment. Cryobiology 29(6): 760. Churchill, T.A. and K.B. Storey. 1992c. Natural freezing survival by painted turtles Chrysemys picta marginata and Chrysemys picta bellii. American Journal of Physiology 262(3 Part 2): R530-R537.

Churchill, T.A. and K.B. Storey. 1992c. Natural freezing survival by painted turtles Chrysemys picta marginata and Chrysemys picta bellii. American Journal of Physiology 262(3 Part 2): R530-R537. Churchill, T.A. and K.B. Storey. 1992d. Responses to freezing exposure of hatchling turtles Trachemys scripta elegans: Factors influencing the development of freeze tolerance by reptiles. Journal of Experimental Biology 167(0): 221-233.

Churchill, T.A. and K.B. Storey. 1992d. Responses to freezing exposure of hatchling turtles Trachemys scripta elegans: Factors influencing the development of freeze tolerance by reptiles. Journal of Experimental Biology 167(0): 221-233. Claussen, D.L. and P.A. Zani. 1991. Allometry of cooling, supercooling and freezing in the freeze-tolerant turtle Chrysemys picta. American Journal of Physiology 261(3 Part 2): R626-R632.

Claussen, D.L. and P.A. Zani. 1991. Allometry of cooling, supercooling and freezing in the freeze-tolerant turtle Chrysemys picta. American Journal of Physiology 261(3 Part 2): R626-R632. Claussen, D.L. and Y. Kim. 1993. The effects of cooling, freezing, and thawing on cardiac and skeletal muscle of the turtle, Chrysemys picta. Journal of Thermal Biology 18(2):91-101.

Claussen, D.L. and Y. Kim. 1993. The effects of cooling, freezing, and thawing on cardiac and skeletal muscle of the turtle, Chrysemys picta. Journal of Thermal Biology 18(2):91-101. Cobell, B. and R. Wagner. 2002. An evaluation of the terrestrial and aquatic resources of Malmstrom Air Force Base. USFWS - Montana Fish and Wildlife Management Assistance Office. 28 pgs + append.

Cobell, B. and R. Wagner. 2002. An evaluation of the terrestrial and aquatic resources of Malmstrom Air Force Base. USFWS - Montana Fish and Wildlife Management Assistance Office. 28 pgs + append. Cochran, P.A. 1986c. The herpetofauna of the Weaver Dunes, Wabasha County, Minnesota (USA). Prairie Naturalist 18(3): 143-150.

Cochran, P.A. 1986c. The herpetofauna of the Weaver Dunes, Wabasha County, Minnesota (USA). Prairie Naturalist 18(3): 143-150. Cochran, P.A. 1987a. Life history notes, Graptemys geographica (map turtle). Adult mortality. Herpetological Review 18(2): 37.

Cochran, P.A. 1987a. Life history notes, Graptemys geographica (map turtle). Adult mortality. Herpetological Review 18(2): 37. Cochran, P.A. 1988. Chrysemys picta (painted turtle). Herpetological Review 19(1): 21.

Cochran, P.A. 1988. Chrysemys picta (painted turtle). Herpetological Review 19(1): 21. Cochran, P.A. 1992. New locality observations for some amphibians and reptiles in Wisconsin. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 27(3): 64.

Cochran, P.A. 1992. New locality observations for some amphibians and reptiles in Wisconsin. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 27(3): 64. Colt, L.C., R.A. Saumure, and S. Baskinger. 1995. First record of the algal genus Basicladia (Chlorophyta, Cladophorales) in Canada. Canadian Field Naturalist 109(4): 454-455.

Colt, L.C., R.A. Saumure, and S. Baskinger. 1995. First record of the algal genus Basicladia (Chlorophyta, Cladophorales) in Canada. Canadian Field Naturalist 109(4): 454-455. Confluence Consulting Inc. 2010. Montana Department of Transportation Wetland Mitigation Monitoring Reports (various sites). MDT Helena, MT.

Confluence Consulting Inc. 2010. Montana Department of Transportation Wetland Mitigation Monitoring Reports (various sites). MDT Helena, MT. Confluence Consulting Inc. 2011. Montana Department of Transportation Wetland Mitigation Monitoring Reports (various sites). MDT Helena, MT.

Confluence Consulting Inc. 2011. Montana Department of Transportation Wetland Mitigation Monitoring Reports (various sites). MDT Helena, MT. Congdon, J.D. and D.W. Tinkle. 1982b. Reproductive energetics of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta). Herpetologica 38(1): 228-337.

Congdon, J.D. and D.W. Tinkle. 1982b. Reproductive energetics of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta). Herpetologica 38(1): 228-337. Congdon, J.D. and J.W. Gibbons. 1985. Egg components and reproductive characteristics of turtles: Relationships to body size. Herpetologica 41(2): 194-205.

Congdon, J.D. and J.W. Gibbons. 1985. Egg components and reproductive characteristics of turtles: Relationships to body size. Herpetologica 41(2): 194-205. Congdon, J.D. and J.W. Gibbons. 1987. Morphological constraint on egg size: A challenge to optimal egg size theory? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 84(12): 4145-4147.

Congdon, J.D. and J.W. Gibbons. 1987. Morphological constraint on egg size: A challenge to optimal egg size theory? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 84(12): 4145-4147. Congdon, J.D. and R.E. Gatten. 1989. Movements and energetics of nesting Chrysemys picta. Herpetologica 45(1): 94-100.

Congdon, J.D. and R.E. Gatten. 1989. Movements and energetics of nesting Chrysemys picta. Herpetologica 45(1): 94-100. Cooley, C.R., A.O. Floyd, A. Dolinger, and P.B. Tucker. 2003. Demography and diet of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) at high-elevation sites in south-western Colorado. Southwestern Naturalist 48(1): 47-53.

Cooley, C.R., A.O. Floyd, A. Dolinger, and P.B. Tucker. 2003. Demography and diet of the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) at high-elevation sites in south-western Colorado. Southwestern Naturalist 48(1): 47-53. Cooper, S.V., C. Jean, and P. Hendricks. 2001. Biological survey of a prairie landscape in Montana's glaciated plains. Report to the Bureau of Land Management. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 24 pp. plus appendices.

Cooper, S.V., C. Jean, and P. Hendricks. 2001. Biological survey of a prairie landscape in Montana's glaciated plains. Report to the Bureau of Land Management. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 24 pp. plus appendices. Cope, E.D. 1872. Report on the recent reptiles and fishes of the survey, collected by Campbell Carrington and C.M. Dawes. pp. 467-469 In: F.V. Hayden, Preliminary report of the United States geological survey of Montana and portions of adjacent territories; being a fifth annual report of progress. 538 pp. 42nd Congress, 2nd Session, House Executive Document Number 326. Serial 1520.

Cope, E.D. 1872. Report on the recent reptiles and fishes of the survey, collected by Campbell Carrington and C.M. Dawes. pp. 467-469 In: F.V. Hayden, Preliminary report of the United States geological survey of Montana and portions of adjacent territories; being a fifth annual report of progress. 538 pp. 42nd Congress, 2nd Session, House Executive Document Number 326. Serial 1520. Cope, E.D. 1875. Check-list of North American Batrachia and Reptilia; with a systematic list of the higher groups, and an essay on geographical distribution. Based on the specimens contained in the U.S. National Museum. U.S. Natioanl Museum Bulletin 1: 1-104.

Cope, E.D. 1875. Check-list of North American Batrachia and Reptilia; with a systematic list of the higher groups, and an essay on geographical distribution. Based on the specimens contained in the U.S. National Museum. U.S. Natioanl Museum Bulletin 1: 1-104. Corn, J. and P. Hendricks. 1998. Lee Metcalf National Wildlife Refuge bullfrog and painted turtle investigations: 1997. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 20 pp.

Corn, J. and P. Hendricks. 1998. Lee Metcalf National Wildlife Refuge bullfrog and painted turtle investigations: 1997. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 20 pp. Costanzo, J.P. 1982. Heating and cooling rates of Terrapene ornate and Chrysemys picta in water. Biosensors and Bioelectrics 53(3):159-166.

Costanzo, J.P. 1982. Heating and cooling rates of Terrapene ornate and Chrysemys picta in water. Biosensors and Bioelectrics 53(3):159-166. Costanzo, J.P., M.F. Wright, and R.E. Lee. 1990. Freeze tolerance and intolerance in hatchling turtles. Cryobiology 27(6): 678.

Costanzo, J.P., M.F. Wright, and R.E. Lee. 1990. Freeze tolerance and intolerance in hatchling turtles. Cryobiology 27(6): 678. Coues, E. and H. Yarrow. 1878. Notes on the herpetology of Dakota and Montana. Bulletin of the U.S. Geological Geographic Survey of the Territories 4: 259-291.

Coues, E. and H. Yarrow. 1878. Notes on the herpetology of Dakota and Montana. Bulletin of the U.S. Geological Geographic Survey of the Territories 4: 259-291. Crawford, K.M. 1991a. The effect of temperature and seasonal acclimatization on renal function of painted turtles, Chrysemys picta. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A 99(3): 375-380.

Crawford, K.M. 1991a. The effect of temperature and seasonal acclimatization on renal function of painted turtles, Chrysemys picta. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A 99(3): 375-380. Crawford, K.M. 1991b. The winter environment of painted turtles, Chrysemys picta: temperature, dissolved oxygen, and potential cues for emergence. Canadian Journal of Zoology 69(9): 2493-2498.

Crawford, K.M. 1991b. The winter environment of painted turtles, Chrysemys picta: temperature, dissolved oxygen, and potential cues for emergence. Canadian Journal of Zoology 69(9): 2493-2498. Crawford, K.M. 1994. Patterns of energy substrate utilization in overwintering painted turtles, Chrysemys picta. Biochemistry and Physiology A Comparative Physiology 109(2): 495-502.

Crawford, K.M. 1994. Patterns of energy substrate utilization in overwintering painted turtles, Chrysemys picta. Biochemistry and Physiology A Comparative Physiology 109(2): 495-502. Crocker, C.E., R.A. Feldman, G.R. Ultsch, and D.C. Jackson. 2000. Overwintering behavior and physiology of eastern painted turtles (Chrysemys picta picta) in Rhode Island. Canadian Journal of Zoology 78(6): 936.

Crocker, C.E., R.A. Feldman, G.R. Ultsch, and D.C. Jackson. 2000. Overwintering behavior and physiology of eastern painted turtles (Chrysemys picta picta) in Rhode Island. Canadian Journal of Zoology 78(6): 936. Crother, B.I. (ed.) 2008. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico. SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 37:1-84.

Crother, B.I. (ed.) 2008. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico. SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 37:1-84. Cserr, H.F., M. DePasquale, and D.C. Jackson. 1988. Brain and cerebrospinal fluid ion composition after long-term anoxia in diving turtles. American Journal of Physiology 255(2)(Ii): R338-R343.

Cserr, H.F., M. DePasquale, and D.C. Jackson. 1988. Brain and cerebrospinal fluid ion composition after long-term anoxia in diving turtles. American Journal of Physiology 255(2)(Ii): R338-R343. D'Allessandro, S.E. and C.H. Ernst. 1995. Additional geographical records for reptiles in Virginia. Herpetology Review 26(4):212-213.

D'Allessandro, S.E. and C.H. Ernst. 1995. Additional geographical records for reptiles in Virginia. Herpetology Review 26(4):212-213. Darrow, T.D. 1961. Food habits of western painted and snapping turtles in southeastern South Dakota and eastern Nebraska. Unpubl. MS Thesis, University of South Dakota, Vermillion.

Darrow, T.D. 1961. Food habits of western painted and snapping turtles in southeastern South Dakota and eastern Nebraska. Unpubl. MS Thesis, University of South Dakota, Vermillion. Day, D. 1989. Montco Terrestrial Wildlife Monitoring Report. Unpublished report for Montco, Billings, Montana.

Day, D. 1989. Montco Terrestrial Wildlife Monitoring Report. Unpublished report for Montco, Billings, Montana. Day, D., P.J. Farmer, and C.E. Farmer. 1989. Montco terrestrial wildlife monitoring report December, 1987 - July, 1989. Montco, Billings, MT, and Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT.

Day, D., P.J. Farmer, and C.E. Farmer. 1989. Montco terrestrial wildlife monitoring report December, 1987 - July, 1989. Montco, Billings, MT, and Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT. DePari, J.A. 1996. Overwintering in the nest chamber by hatchling painted turtles, Chrysemys picta, in northern New Jersey. Chelonian Conservation Biology 2(1):5-12.

DePari, J.A. 1996. Overwintering in the nest chamber by hatchling painted turtles, Chrysemys picta, in northern New Jersey. Chelonian Conservation Biology 2(1):5-12. DeRosa, C.T. 1978. A comparison of orientation mechanisms in aquatic, semi-aquatic and terrestial turtles (Trionyx spinifer, Chrysemys picta and Terrapene c. carolina). Ph.D. Dissertation, Miami University 99p.

DeRosa, C.T. 1978. A comparison of orientation mechanisms in aquatic, semi-aquatic and terrestial turtles (Trionyx spinifer, Chrysemys picta and Terrapene c. carolina). Ph.D. Dissertation, Miami University 99p. DeRosa, C.T. and D.H. Taylor. 1978. Sun-compass orientation in the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta (Reptilia, Testudines, Testudinidae). Journal of Herpetology 12(1): 25-28.

DeRosa, C.T. and D.H. Taylor. 1978. Sun-compass orientation in the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta (Reptilia, Testudines, Testudinidae). Journal of Herpetology 12(1): 25-28. DeRosa, C.T. and D.H. Taylor. 1980. Homeward orientation mechanisms in three species of turtles (Trionyx spinifer, Chrysemys picta, and Terrapene carolina). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiololgy 7(1):15-23.

DeRosa, C.T. and D.H. Taylor. 1980. Homeward orientation mechanisms in three species of turtles (Trionyx spinifer, Chrysemys picta, and Terrapene carolina). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiololgy 7(1):15-23. DeRosa, C.T. and D.H. Taylor. 1982. A comparison of compass orientation mechanisms in three turtles (Trionyx spinifer, Chrysemys picta, and Terrapene carolina). Copeia 1982: 394-399.

DeRosa, C.T. and D.H. Taylor. 1982. A comparison of compass orientation mechanisms in three turtles (Trionyx spinifer, Chrysemys picta, and Terrapene carolina). Copeia 1982: 394-399. Differences in habitat use by Blanding's turtles, Emydoidea blandingii, and Painted turtles, Chysemys picta, in the Nebraska Sandhills. American Midland Naturalist 149: 241-244.

Differences in habitat use by Blanding's turtles, Emydoidea blandingii, and Painted turtles, Chysemys picta, in the Nebraska Sandhills. American Midland Naturalist 149: 241-244. Dimond, M.T. 1979. Sex differentiation and incubation temperature in turtles. American Zoology 19(3): 981.

Dimond, M.T. 1979. Sex differentiation and incubation temperature in turtles. American Zoology 19(3): 981. Dimond, M.T. 1983. Sex of turtle hatchlings as related to incubation temperature. Annual Reptile Symposium on Captive Propagation and Husbandry Proceedings 6 1982[1983]: 88-101, illustr.

Dimond, M.T. 1983. Sex of turtle hatchlings as related to incubation temperature. Annual Reptile Symposium on Captive Propagation and Husbandry Proceedings 6 1982[1983]: 88-101, illustr. Dood, A.R. 1980. Terry Badlands nongame survey and inventory final report. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks and Bureau of Land Management, Helena, MT. 70 pp.

Dood, A.R. 1980. Terry Badlands nongame survey and inventory final report. Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks and Bureau of Land Management, Helena, MT. 70 pp. Drought, J.F. 1987a. Chrysemys picta marginata (midland painted turtle). Herpetological Review 18(1): 21.

Drought, J.F. 1987a. Chrysemys picta marginata (midland painted turtle). Herpetological Review 18(1): 21. Dubois, W. 1982. Testis structure and function in the fresh water turtle Chrysemys picta. Ph.D. Dissertation, Boston University Graduate School. 205 p.

Dubois, W. 1982. Testis structure and function in the fresh water turtle Chrysemys picta. Ph.D. Dissertation, Boston University Graduate School. 205 p. Dubois, W., J. Pudney, and I.P. Callard. 1988. The annual testicular cycle in the turtle, Chrysemys picta: a histochemical and electron microscopic study. General and Comparative Endocrinology 71(2): 191-204.

Dubois, W., J. Pudney, and I.P. Callard. 1988. The annual testicular cycle in the turtle, Chrysemys picta: a histochemical and electron microscopic study. General and Comparative Endocrinology 71(2): 191-204. Dunson, W.A. and H. Heatwole. 1986. Effect of relative shell size in turtles on water and electrolyte composition. American Journal of Physiology 250(6)(Ii): R1133-R1137.

Dunson, W.A. and H. Heatwole. 1986. Effect of relative shell size in turtles on water and electrolyte composition. American Journal of Physiology 250(6)(Ii): R1133-R1137. ECON, Inc. (Ecological Consulting Service), Helena, MT., 1976, Colstrip 10 x 20 Area wildlife and wildlife habitat annual monitoring report, 1976. Proj. 135-85-A. December 31, 1976.

ECON, Inc. (Ecological Consulting Service), Helena, MT., 1976, Colstrip 10 x 20 Area wildlife and wildlife habitat annual monitoring report, 1976. Proj. 135-85-A. December 31, 1976. Econ, Inc. 1988. Wildlife monitoring report, 1987 field season, Big Sky Mine. March 1988. In Peabody Mining and Reclamation Plan Big Sky Mine Area B. Vol. 8, cont., Tab 10 - Wildlife Resources. Appendix 10-1, 1987 Annual Wildlife Report.

Econ, Inc. 1988. Wildlife monitoring report, 1987 field season, Big Sky Mine. March 1988. In Peabody Mining and Reclamation Plan Big Sky Mine Area B. Vol. 8, cont., Tab 10 - Wildlife Resources. Appendix 10-1, 1987 Annual Wildlife Report. Elrod, M.J. 1902. A biological reconnoissance in the vicinity of Flathead Lake. Bulletin of the University of Montana Number, Biological Series 10(3):89-182.

Elrod, M.J. 1902. A biological reconnoissance in the vicinity of Flathead Lake. Bulletin of the University of Montana Number, Biological Series 10(3):89-182. Ernst, C.H. 1964. Social dominance and aggressiveness in a juvinile Chrysemys picta picta. Bulletin of the Philadelphia Herpetological Society 13: 18-19.

Ernst, C.H. 1964. Social dominance and aggressiveness in a juvinile Chrysemys picta picta. Bulletin of the Philadelphia Herpetological Society 13: 18-19. Ernst, C.H. 1967. Intergradation between the painted turtles Chrysemys picta picta and Chrysemys picta dorsalis. Copeia 1967: 131-136.

Ernst, C.H. 1967. Intergradation between the painted turtles Chrysemys picta picta and Chrysemys picta dorsalis. Copeia 1967: 131-136. Ernst, C.H. 1970. The status of the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta, in Tennessee and Kentucky. Journal of Herpetology 4: 39-45.

Ernst, C.H. 1970. The status of the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta, in Tennessee and Kentucky. Journal of Herpetology 4: 39-45. Ernst, C.H. 1971b. Growth of the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta, in southeastern Pennsylvania. Herpetologica 27(2): 135-141.

Ernst, C.H. 1971b. Growth of the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta, in southeastern Pennsylvania. Herpetologica 27(2): 135-141. Ernst, C.H. 1971c. Population dynamics and activity cycles of Chrysemys picta in southeastern Pennsylvania. Journal of Herpetology 5: 151-160.

Ernst, C.H. 1971c. Population dynamics and activity cycles of Chrysemys picta in southeastern Pennsylvania. Journal of Herpetology 5: 151-160. Ernst, C.H. 1971d. Seasonal incidence of leech infestation on the painted turtle Chrysemys picta. Journal of Parasitol. 57: 32.

Ernst, C.H. 1971d. Seasonal incidence of leech infestation on the painted turtle Chrysemys picta. Journal of Parasitol. 57: 32. Ernst, C.H. 1971e. Sexual cycles and maturity of the turtle, Chrysemys picta. Biology Bulletin 140(2): 191-200.

Ernst, C.H. 1971e. Sexual cycles and maturity of the turtle, Chrysemys picta. Biology Bulletin 140(2): 191-200. Ernst, C.H. 1974. Effects of Hurricane Agnes on a painted turtle population. Journal of Herpetology 8(3): 237-240.

Ernst, C.H. 1974. Effects of Hurricane Agnes on a painted turtle population. Journal of Herpetology 8(3): 237-240. Ernst, C.H. and B.S. McDonald. 1989. Preliminary report on enhanced growth and early maturity in a Maryland population of painted turtles, Chrysemys picta. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 25(4) 1989: 135-142.

Ernst, C.H. and B.S. McDonald. 1989. Preliminary report on enhanced growth and early maturity in a Maryland population of painted turtles, Chrysemys picta. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 25(4) 1989: 135-142. Ernst, C.H. and E. M. Ernst. 1973. Biology of Chrysemys picta bellii in southwestern Minnesota. Journal of the Minnesota Academy of Science 38(2, 3): 77-80.

Ernst, C.H. and E. M. Ernst. 1973. Biology of Chrysemys picta bellii in southwestern Minnesota. Journal of the Minnesota Academy of Science 38(2, 3): 77-80. Ernst, C.H. and E.M Ernst. 1971a. Chrysemys picta. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 106: 1-106.

Ernst, C.H. and E.M Ernst. 1971a. Chrysemys picta. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 106: 1-106. Ernst, C.H. and E.M. Ernst. 1980. Relationships between North American turtles of the Chrysemys complex as indicated by their Endoparasitic Helminths. Proceedings of the Biological Society in Washington 93(2): 339-345.

Ernst, C.H. and E.M. Ernst. 1980. Relationships between North American turtles of the Chrysemys complex as indicated by their Endoparasitic Helminths. Proceedings of the Biological Society in Washington 93(2): 339-345. Ernst, C.H. and E.M.Ernst. 1971b. The taxonomic status and zoogeography of the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta, in Pennsylvania. Herpetologica 27(4) :390-396.

Ernst, C.H. and E.M.Ernst. 1971b. The taxonomic status and zoogeography of the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta, in Pennsylvania. Herpetologica 27(4) :390-396. Ernst, C.H. and J.A. Fowler. 1977. Taxonomic status of the turtle, Chrysemys picta, in the Northern peninsula of Michigan. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 90(3): 685-689.

Ernst, C.H. and J.A. Fowler. 1977. Taxonomic status of the turtle, Chrysemys picta, in the Northern peninsula of Michigan. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 90(3): 685-689. Essner, R. and A.J. Hendershott. 1996. County records for reptiles and amphibians in Missouri found in the vertebrate museum at Southeast Missouri State University. Herpetology Review 27(4):218.

Essner, R. and A.J. Hendershott. 1996. County records for reptiles and amphibians in Missouri found in the vertebrate museum at Southeast Missouri State University. Herpetology Review 27(4):218. Etchberger, C.R., M.A. Ewert, B.A. Raper, and C.E. Nelson. 1992. Do low incubation temperatures yield females in painted turtles? Canadian Journal of Zoology 70(2): 391-394.

Etchberger, C.R., M.A. Ewert, B.A. Raper, and C.E. Nelson. 1992. Do low incubation temperatures yield females in painted turtles? Canadian Journal of Zoology 70(2): 391-394. Evans, L.T. 1940. Effects of light and hormones upon the activity of young turtles, Chrysemys picta. Biology Bulletin 79(2): 370-371.

Evans, L.T. 1940. Effects of light and hormones upon the activity of young turtles, Chrysemys picta. Biology Bulletin 79(2): 370-371. Evans, L.T. 1940. Effects of testosterone propionate upon social dominance in young turtles, Chrysemys picta. Biology Bulletin 79: 371.

Evans, L.T. 1940. Effects of testosterone propionate upon social dominance in young turtles, Chrysemys picta. Biology Bulletin 79: 371. Farmer, P. 1980. Terrestrial wildlife monitoring study, Pearl area, Montana June, 1978 - May, 1980. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT.

Farmer, P. 1980. Terrestrial wildlife monitoring study, Pearl area, Montana June, 1978 - May, 1980. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT. Farmer, P. and S.B. Heath. 1987. Wildlife baseline inventory, Rock Creek study area, Sanders County, Montana. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT.

Farmer, P. and S.B. Heath. 1987. Wildlife baseline inventory, Rock Creek study area, Sanders County, Montana. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT. Farmer, P. J. 1980. Terrestrial Wildlife Monitoring Study, Pearl Area, Montana, June, 1978 - May, 1980. Tech. Rep. by WESTECH for Shell Oil Co.

Farmer, P. J. 1980. Terrestrial Wildlife Monitoring Study, Pearl Area, Montana, June, 1978 - May, 1980. Tech. Rep. by WESTECH for Shell Oil Co. Feder, M.E. 1983. The relation of air breathing and locomotion to predation on tadpoles, Rana berlandieri, by turtles. Physiological Zoology 56(4): 522-531.

Feder, M.E. 1983. The relation of air breathing and locomotion to predation on tadpoles, Rana berlandieri, by turtles. Physiological Zoology 56(4): 522-531. Feigley, H. P. 1997. Colonial nesting bird survey on the Bureau of Land Management Lewistown District: 1996. Unpublished report, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Lewistown, Montana.

Feigley, H. P. 1997. Colonial nesting bird survey on the Bureau of Land Management Lewistown District: 1996. Unpublished report, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Lewistown, Montana. Fishbeck, D.W. and E.C. Bovee. 1993. Two new amoebae, Striamoeba sparolata n. sp. and Flamella tiara n. sp., from fresh water. Ohio Journal of Science 93(5): 134-139.

Fishbeck, D.W. and E.C. Bovee. 1993. Two new amoebae, Striamoeba sparolata n. sp. and Flamella tiara n. sp., from fresh water. Ohio Journal of Science 93(5): 134-139. Fjell, Alan K., 1986, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1985 field season. March 1986.

Fjell, Alan K., 1986, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1985 field season. March 1986. Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan., 1983, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1982 field season. May 1983.

Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan., 1983, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1982 field season. May 1983. Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan., 1985, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1984 field season. February 1985.

Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan., 1985, Peabody Coal Company Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1984 field season. February 1985. Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan., 1987, Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1986 field season. April 1987.

Fjell, Alan K., and Brian R. Mahan., 1987, Big Sky Mine, Rosebud County, MT. Wildlife monitoring report: 1986 field season. April 1987. Flath, D.L. 2002. Reptile and amphibian surveys in the Madison-Missouri River Corridor, Montana. Annual Progress Report. 14pp.

Flath, D.L. 2002. Reptile and amphibian surveys in the Madison-Missouri River Corridor, Montana. Annual Progress Report. 14pp. Foster, B.J., D.W. Sparks, and J.E. Duchamp. 2003. Urban herpetology I: New distribution records of amphibians and reptiles from Hendricks County, Indiana. Herpetological Review 34(4):395.

Foster, B.J., D.W. Sparks, and J.E. Duchamp. 2003. Urban herpetology I: New distribution records of amphibians and reptiles from Hendricks County, Indiana. Herpetological Review 34(4):395. Fowle, S.C. 1996. The Painted Turtle in the Mission Valley of western Montana. M.S. thesis. University of Montana. Missoula, MT. 101 pp.

Fowle, S.C. 1996. The Painted Turtle in the Mission Valley of western Montana. M.S. thesis. University of Montana. Missoula, MT. 101 pp. Fowle, S.C. 1996a. The effects of roadkill mortality on the western painted turtle in the Mission Valley, Western Montana. Abstract. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 2(2): 39.

Fowle, S.C. 1996a. The effects of roadkill mortality on the western painted turtle in the Mission Valley, Western Montana. Abstract. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 2(2): 39. Frazer, N.B., J.W. Gibbons, and J.L. Greene. 1991. Growth, survivorship and longevity of painted turtles (Chrysemys picta) in a southwestern Michigan marsh. American Midland Naturalist 125: 245-258.

Frazer, N.B., J.W. Gibbons, and J.L. Greene. 1991. Growth, survivorship and longevity of painted turtles (Chrysemys picta) in a southwestern Michigan marsh. American Midland Naturalist 125: 245-258. Frazer, N.B., J.W. Gibbons, and J.L. Greene. 1993. Temporal variation in growth rate and age at maturity of male painted turtles, Chrysemys picta. American Midland Naturalist 130: 314-324.