View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Idaho Giant Salamander - Dicamptodon aterrimus

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is found in a restricted area of western Montana along and adjacent to the Idaho border. Occupancy of historic streams appears stable. It faces threats from warming water temperatures and the impacts of timber harvest and fire are unknown.

General Description

EGGS

Eggs are laid singly, but placed together in a mass approximately 15 cm (5.9 in) wide by 20 cm (7.9 in) long containing 129 to 200 eggs (Nussbaum et al. 1983; Jones et al. 1990). Each ovum is pure white and is surrounded by six clear jelly layers (Nussbaum et al. 1983). Ovum diameters are approximately 6.5 mm (0.26 in) (Nussbaum et al. 1983). The eggs are oblong and attached on a short pedicle to the substrate in flowing water. Total egg widths are 16-21 mm (0.6-0.8 in) and total egg heights are 22-33 mm (0.9-1.3 in), including the jelly layers (Jones et al. 1990).

LARVAE

Short external feathery gills are present at the base of the head. Body color varies to match the local substrate, but they usually have a dark dorsal color with lighter stripes behind the eyes (Nussbaum et al. 1983). The dorsal tail fin is mottled and begins at or behind the rear limbs. Hatchlings have a total length (TL) of 34 to 40 mm (1.3-1.6 in) and reproductively mature larvae (neotenic) larvae may reach a TL of 351 mm (13.8 in) (Nussbaum et al. 1983; Jones et al. 1990).

JUVENILES AND ADULTS

Dorsal color is dark brown or almost black in base color and light tan or coppery marbling is usually present and is often brightest on the head (Nussbaum et al. 1983). They are heavy-bodied, with a large head and muscular legs. The size of new metamorphs is highly variable but adults may reach a TL of up to 340 mm (13.4 in) (Nussbaum et al. 1983).

Diagnostic Characteristics

No other salamander would be found as an aquatic inhabitant of streams in Montana. Adult Idaho Giant Salamanders are 3-4 times larger than that of adults of Long-toed (

Ambystoma macrodactylum) and Western Tiger Salamanders (

A. mavortium). Other larval salamanders found in Montana live in ponds, have long, feathery gills, and a dorsal fin originating far forward of the rear legs.

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Western Hemisphere Range

Range Comments

In 2005, Idaho Giant Salamander were confirmed to be present in Mineral County south of Haugan by Jennifer Copenhaver of the Lolo National Forest. Electrofishing surveys in the same region in 2006 and 2007 detected more than 100 individuals in 51 different portions of 11 different tributaries of 3 major watersheds. Prior to these observations, the species had been reported or illustrated as occurring in Mineral and Ravalli counties by several authors (Anderson 1969; Black 1970a; Daugherty et al. 1983; Stebbins 2003; Good 1989; Reichel and Flath 1995; Petranka 1998). However, as noted by Nussbaum (1976) and Savage (1952) all these distributional claims were apparently based on the assumption that the holotype specimen (USNM 5242) described by Cope (1867) and later by Cope (1889) as being collected by Lieutenant Mullan from the “North Rocky Mountains” was actually collected in western Montana. Thus, prior to the detection in 2005 there was no valid documentation of their presence in the state (Franz 1971; Nussbaum 1976; Maxell et al. 2003; Werner et al. 2004).

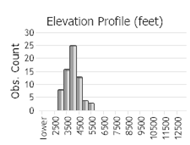

Maximum elevation: 1,737 m (5,700 ft) in Mineral County (Eric Dallalio and Phil Jellen, personal communication; MTNHP 2007).

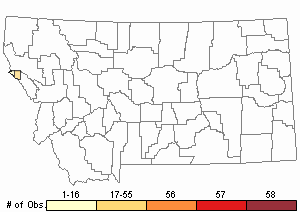

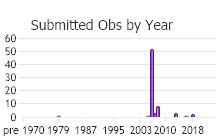

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 73

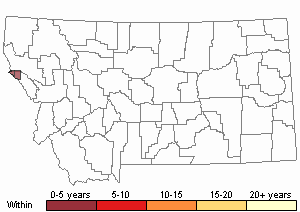

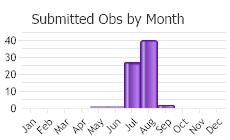

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

Non-migratory.

Habitat

Larvae and aquatic adults are the most likely life history stage to be observed as they may reach high densities in the pools of swift, cold mountain streams and may also be found in lakes or ponds (Nussbaum et al. 1983; Reichel and Flath 1995). Terrestrial adults are seldom seen and can be found in moist coniferous forests under rocks, bark and logs and aquatically under stones in mountain streams or lakes up to 2,165 m (7,100 ft). Adults are active terrestrially on warm, rainy nights (Nussbaum et al. 1983).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Forest and Woodland

Montane - Subalpine Forest and Woodland

Wetland and Riparian

Riparian and Wetland Forest

Open Water

Streams and Rivers (Lotic) - Northern Rockies

Recently Disturbed or Modified

Harvested Forest

Food Habits

Adults may feed on a variety of invertebrates and small vertebrates. Females do not feed for the seven months spent in nest with eggs. Larvae feed on fish and invertebrates, but diet is influenced by their size. It can consist of Trichoptera larvae, Plecoptera nymphs, Coleoptera larvae, Ephemeroptera nymphs/Coleoptera adults. Additionally,

Ascaphus larvae may be important food for larger larvae (Metter 1963; Nussbaum et al. 1983).

Ecology

Larvae usually metamorphose in 18-24 months but may become sexually mature (paedogenesis) and reproduce as larvae (Nussbaum et al. 1983; Parker 1993). Neoteny is uncommon in small streams, but neotenes may constitute major breeding force of populations in large streams and ponds/lakes (Nussbaum and Clothier 1973).

Reproductive Characteristics

Adults breed in the spring or fall in hidden water-filled nest chambers beneath logs and stones or in crevices in mountain streams or lakes. Ovipostioning occurs in spring (May in coastal regions) and fall (noted in Idaho) with incubation lasting for 275 days. Females guard the eggs throughout the incubation period; therefore, they likely only breed during alternate years (Nussbaum 1969; Nussbaum et al. 1983). Larvae hatch at snout-vent length (SVL) 18.25 mm (0.72 in), but do not feed for 3 to 4 more months until they are 24.43 mm (0.96 in) SVL. Metamorphose occurs during the second year (Nussbaum and Clothier 1973).

Management

The following was taken from the Status and Conservation section for the Idaho Giant Salamander account in

Maxell et al. 2009Potential threats for the species across its global range probably apply also to Montana populations. Because Idaho Giant Salamanders were only recently confirmed in Montana, the extent of their distribution and conservation status are still largely uncertain. However, because their distribution appears to be limited to a handful of headwater streams adjacent to the Idaho border, they face a variety of risks associated with limited distribution. The range of the Idaho Giant Salamander in Montana has likely been reduced during the last century through habitat fragmentation from logging of mature and old-growth forest types, wildland fire and fire management activities, road building, placer mining and the use of piscicides. The species is more likely to occur in road-less areas (Sepulveda and Lowe 2009), so changes in land use over the last century have undoubtedly impacted this species. Individual studies that specifically identify risk factors or other issues relevant to the conservation of Idaho Giant Salamanders have not been reviewed at this time. Routine monitoring of known populations should be conducted to identify threats to each, as well as to determine their continued viability. Additional stream surveys are desirable to determine connectivity with adjacent Idaho populations, especially between Thompson Falls and Lolo Pass (Maxell et al. 2009).

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Anderson, J.D. 1969. Dicamptodon and D. ensatus. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Pp. 76.1-76.2.

Anderson, J.D. 1969. Dicamptodon and D. ensatus. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Pp. 76.1-76.2. Black, J.H. 1970a. Amphibians of Montana. Montana Wildlife, Montana Fish and Game Commission. Animals of Montana Series 1970(1): 1-32.

Black, J.H. 1970a. Amphibians of Montana. Montana Wildlife, Montana Fish and Game Commission. Animals of Montana Series 1970(1): 1-32. Cope, E.D. 1867. A review of the species of the Amblystomidae. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 19: 166-211.

Cope, E.D. 1867. A review of the species of the Amblystomidae. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 19: 166-211. Cope, E.D. 1889. The Batrachia of North America. Bulletin of the U.S. National Museum 34: 1-525, figs. 1-119, pls. 1-86.

Cope, E.D. 1889. The Batrachia of North America. Bulletin of the U.S. National Museum 34: 1-525, figs. 1-119, pls. 1-86. Daugherty, C.H., F.W. Allendorf, W.W. Dunlap and K.L. Knudsen. 1983. Systematic implications of geographic patterns of genetic variation in the genus Dicamptodon. Copeia 1983: 679-691.

Daugherty, C.H., F.W. Allendorf, W.W. Dunlap and K.L. Knudsen. 1983. Systematic implications of geographic patterns of genetic variation in the genus Dicamptodon. Copeia 1983: 679-691. Franz, R. 1971. Notes on the distribution and ecology of the herpetofauna of northwestern Montana. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 7: 1-10.

Franz, R. 1971. Notes on the distribution and ecology of the herpetofauna of northwestern Montana. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 7: 1-10. Good, D.A. 1989. Hybridization and cryptic species in Dicamptodon Caudata Dicamptodontidae. Evolution 43(4): 728-744.

Good, D.A. 1989. Hybridization and cryptic species in Dicamptodon Caudata Dicamptodontidae. Evolution 43(4): 728-744. Jones, L.L.C., R.B. Bury and P.S. Corn. 1990. Field observation of the development of a clutch of pacific giant salamander (Dicamptodon tenebrosus) eggs. Northwestern Naturalist 71: 93-94.

Jones, L.L.C., R.B. Bury and P.S. Corn. 1990. Field observation of the development of a clutch of pacific giant salamander (Dicamptodon tenebrosus) eggs. Northwestern Naturalist 71: 93-94. Maxell, B.A., J.K. Werner, P. Hendricks, and D.L. Flath. 2003. Herpetology in Montana: a history, status summary, checklists, dichotomous keys, accounts for native, potentially native, and exotic species, and indexed bibliography. Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology, Northwest Fauna Number 5. Olympia, WA. 135 p.

Maxell, B.A., J.K. Werner, P. Hendricks, and D.L. Flath. 2003. Herpetology in Montana: a history, status summary, checklists, dichotomous keys, accounts for native, potentially native, and exotic species, and indexed bibliography. Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology, Northwest Fauna Number 5. Olympia, WA. 135 p. Maxell, B.A., P. Hendricks, M.T. Gates, and S. Lenard. 2009. Montana amphibian and reptile status assessment, literature review, and conservation plan, June 2009. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 643 p.

Maxell, B.A., P. Hendricks, M.T. Gates, and S. Lenard. 2009. Montana amphibian and reptile status assessment, literature review, and conservation plan, June 2009. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 643 p. Metter, D.E. 1963. Stomach contents of Idaho larval Dicamptodon. Copeia (2): 435-436.

Metter, D.E. 1963. Stomach contents of Idaho larval Dicamptodon. Copeia (2): 435-436. Nussbaum, R .A. and G. W. Clothier. 1973. Population structure, growth, and size of larval Dicamptodon ensatus (Eschscholtz). Northwest Science 47(4): 218-227.

Nussbaum, R .A. and G. W. Clothier. 1973. Population structure, growth, and size of larval Dicamptodon ensatus (Eschscholtz). Northwest Science 47(4): 218-227. Nussbaum, R.A. 1969. Nests and eggs of the Pacific giant salamander Dicamptodon ensatus (Eschscholtz). Herpetologica 25: 257-262.

Nussbaum, R.A. 1969. Nests and eggs of the Pacific giant salamander Dicamptodon ensatus (Eschscholtz). Herpetologica 25: 257-262. Nussbaum, R.A. 1976. Geographic variation and systematics of the salamanders of the genus Dicamptodon Strauch (Ambystomatidae). Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan Miscellaneous Publication Number 149. 94 pp.

Nussbaum, R.A. 1976. Geographic variation and systematics of the salamanders of the genus Dicamptodon Strauch (Ambystomatidae). Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan Miscellaneous Publication Number 149. 94 pp. Nussbaum, R.A., E.D. Brodie, Jr. and R.M. Storm. 1983. Amphibians and reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. University of Idaho Press. Moscow, ID. 332 pp.

Nussbaum, R.A., E.D. Brodie, Jr. and R.M. Storm. 1983. Amphibians and reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. University of Idaho Press. Moscow, ID. 332 pp. Petranka, J.W. 1998. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C. 587 pp.

Petranka, J.W. 1998. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C. 587 pp. Reichel, J. and D. Flath. 1995. Identification of Montana's amphibians and reptiles. Montana Outdoors 26(3):15-34.

Reichel, J. and D. Flath. 1995. Identification of Montana's amphibians and reptiles. Montana Outdoors 26(3):15-34. Savage, J.M. 1952. The distribution of the Pacific giant salamander, Dicamptodon ensatus, east of the Cascade Mountains. Copeia 1952: 183.

Savage, J.M. 1952. The distribution of the Pacific giant salamander, Dicamptodon ensatus, east of the Cascade Mountains. Copeia 1952: 183. Sepulveda, A.J. and W.H. Lowe. 2009. Local and Landscape-Scale Influences on the Occurrence and Density of Dicamptodon aterrimus, the Idaho Giant Salamander. Journal of Herpetology 43(3), 469-484.

Sepulveda, A.J. and W.H. Lowe. 2009. Local and Landscape-Scale Influences on the Occurrence and Density of Dicamptodon aterrimus, the Idaho Giant Salamander. Journal of Herpetology 43(3), 469-484. Stebbins, R. C. 2003. A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York. 533 p.

Stebbins, R. C. 2003. A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York. 533 p. Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks and D.L. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and Reptiles of Montana. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, MT. 262 pp.

Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks and D.L. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and Reptiles of Montana. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, MT. 262 pp.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Antonelli, A.L., R.A. Nussbaum and S.D. Smith. 1972. Comparative food habits of four species of stream-dwelling vertebrates (Dicamptodon ensatus, D. copei, Cottus tenius, Salmo gairdnei) Northwest Science 46: 277-289.

Antonelli, A.L., R.A. Nussbaum and S.D. Smith. 1972. Comparative food habits of four species of stream-dwelling vertebrates (Dicamptodon ensatus, D. copei, Cottus tenius, Salmo gairdnei) Northwest Science 46: 277-289. Blaustein, A.R., J.J. Beatty, H. Deanna, and R.M. Storm. 1995. The biology of amphibians and reptiles in old-growth forests in the Pacific Northwest. General Technical Report PNW-GTR-337. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 98 p.

Blaustein, A.R., J.J. Beatty, H. Deanna, and R.M. Storm. 1995. The biology of amphibians and reptiles in old-growth forests in the Pacific Northwest. General Technical Report PNW-GTR-337. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 98 p. Boundy, J. 2001. Herpetofaunal surveys in the Clark Fork Valley region, Montana. Herpetological Natural History 8: 15-26.

Boundy, J. 2001. Herpetofaunal surveys in the Clark Fork Valley region, Montana. Herpetological Natural History 8: 15-26. Brunson, R.B. 1955. Check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 15: 27-29.

Brunson, R.B. 1955. Check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 15: 27-29. Bury, R.B. 1972. Small mammals and other prey in the diet of the Pacific Giant salamander (Dicamptodon ensatus). American Midland Naturalist 87(2): 524-526.

Bury, R.B. 1972. Small mammals and other prey in the diet of the Pacific Giant salamander (Dicamptodon ensatus). American Midland Naturalist 87(2): 524-526. Carlson, J. (Coordinator, Montana Animal Species of Concern Committee). 2003. Montana Animal Species of Concern January 2003. Helena, MT: Montana Natural Heritage Program and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. In Press. 12p.

Carlson, J. (Coordinator, Montana Animal Species of Concern Committee). 2003. Montana Animal Species of Concern January 2003. Helena, MT: Montana Natural Heritage Program and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. In Press. 12p. Cassirer, E.F. 1995. Wildlife inventory, Craig Mountain, Idaho. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Lewiston Idaho. 182 pp.

Cassirer, E.F. 1995. Wildlife inventory, Craig Mountain, Idaho. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Lewiston Idaho. 182 pp. Cochran, D.C. 1961. Type specimens of reptiles and amphibians in the United States National Museum. U.S. National Museum Bulletin (220) xv + 291pp.

Cochran, D.C. 1961. Type specimens of reptiles and amphibians in the United States National Museum. U.S. National Museum Bulletin (220) xv + 291pp. Connor, E.J., W.J. Trush, and A.W. Knight. 1988. Effects of logging on Pacific giant salamanders: influence of age-class composition and habitat complexity. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 69 (Suppl.): 104-105.

Connor, E.J., W.J. Trush, and A.W. Knight. 1988. Effects of logging on Pacific giant salamanders: influence of age-class composition and habitat complexity. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 69 (Suppl.): 104-105. Cope, E.D. 1867. Proceedings of the Academy of National Sciences, Philadelphia, Volume 19, 2nd Series, p. 201.

Cope, E.D. 1867. Proceedings of the Academy of National Sciences, Philadelphia, Volume 19, 2nd Series, p. 201. Cope, E.D. 1875. Check-list of North American Batrachia and Reptilia; with a systematic list of the higher groups, and an essay on geographical distribution. Based on the specimens contained in the U.S. National Museum. U.S. Natioanl Museum Bulletin 1: 1-104.

Cope, E.D. 1875. Check-list of North American Batrachia and Reptilia; with a systematic list of the higher groups, and an essay on geographical distribution. Based on the specimens contained in the U.S. National Museum. U.S. Natioanl Museum Bulletin 1: 1-104. Coues, E. and H. Yarrow. 1878. Notes on the herpetology of Dakota and Montana. Bulletin of the U.S. Geological Geographic Survey of the Territories 4: 259-291.

Coues, E. and H. Yarrow. 1878. Notes on the herpetology of Dakota and Montana. Bulletin of the U.S. Geological Geographic Survey of the Territories 4: 259-291. Crother, B.I. (ed.) 2008. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico. SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 37:1-84.

Crother, B.I. (ed.) 2008. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico. SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 37:1-84. Daugherty, C.H. and F.W. Allendorf. 1977b. The taxonomic value of genetic distance: data from two amphibians. Abstract. American Zoologist 17(4): 973.

Daugherty, C.H. and F.W. Allendorf. 1977b. The taxonomic value of genetic distance: data from two amphibians. Abstract. American Zoologist 17(4): 973. Dethlefson, E.S. 1948. A subterranean nest of the Pacific giant salamander, Dicamptodon ensatus (Eschscholtz). Wasmann Collector 7: 81-84.

Dethlefson, E.S. 1948. A subterranean nest of the Pacific giant salamander, Dicamptodon ensatus (Eschscholtz). Wasmann Collector 7: 81-84. Flath, D.L. 1979. Nongame species of special interest or concern: Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes. Wildlife Division, Montana Department of Fish and Game. Helena, MT.

Flath, D.L. 1979. Nongame species of special interest or concern: Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes. Wildlife Division, Montana Department of Fish and Game. Helena, MT. Flath, D.L. 1998. Species of special interest or concern. Montana Department of Fish, Widlife and Parks, Helena, MT. March, 1998. 7 p.

Flath, D.L. 1998. Species of special interest or concern. Montana Department of Fish, Widlife and Parks, Helena, MT. March, 1998. 7 p. Franz, R. 1970a. Additional notes on the feeding of larval giant salamanders, Dicamptodon ensatus. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 6(3): 51-52.

Franz, R. 1970a. Additional notes on the feeding of larval giant salamanders, Dicamptodon ensatus. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 6(3): 51-52. Hendricks, P. and J.D. Reichel. 1996a. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Bitterroot National Forest: 1995. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 95 p.

Hendricks, P. and J.D. Reichel. 1996a. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Bitterroot National Forest: 1995. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 95 p. Honeycutt, R.K., W.H. Lowe, and B.R. Hossack. 2016. Movement and survival of an amphibian in relation to sediment and culvert design. The Journal of Wildlife Management 80(4):761-770.

Honeycutt, R.K., W.H. Lowe, and B.R. Hossack. 2016. Movement and survival of an amphibian in relation to sediment and culvert design. The Journal of Wildlife Management 80(4):761-770. Honeycutt, Richard K. 2014. Effects of road-stream crossings on populations of the Idaho Giant Salamander (Dicamptodon aterrimus). M.S. Thesis. University of Montana. Missoula, MT.

Honeycutt, Richard K. 2014. Effects of road-stream crossings on populations of the Idaho Giant Salamander (Dicamptodon aterrimus). M.S. Thesis. University of Montana. Missoula, MT. Isaak, D.J., M. Dumelle, D.L. Horan, D.H. Mason, T.W. Franklin, D.E. Nagel, J.M. Ver Hoef, and M.K. Young. 2025. Improving species distribution models for stream networks by incorporating spatial autocorrelation in multi-sourced datasets: a range-wide assessment of Idaho Giant Salamander status and future risks. Diversity and Distributions 2025; 31:e70085.

Isaak, D.J., M. Dumelle, D.L. Horan, D.H. Mason, T.W. Franklin, D.E. Nagel, J.M. Ver Hoef, and M.K. Young. 2025. Improving species distribution models for stream networks by incorporating spatial autocorrelation in multi-sourced datasets: a range-wide assessment of Idaho Giant Salamander status and future risks. Diversity and Distributions 2025; 31:e70085. Jones, Lawrence L. C., W. P. Leonard and D. H. Olson, eds. 2005. Amphibians of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle Audubon Society: Seattle, WA, 227 pp.

Jones, Lawrence L. C., W. P. Leonard and D. H. Olson, eds. 2005. Amphibians of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle Audubon Society: Seattle, WA, 227 pp. Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. Kelsey, K.A. 1994. Responses of headwater stream amphibians to forest practices in western Washington. Northwest Science 68(2): 133.

Kelsey, K.A. 1994. Responses of headwater stream amphibians to forest practices in western Washington. Northwest Science 68(2): 133. Kessel, E.L. and B.B. Kessel. 1943a. The rate of growth of older larvae of the Pacific giant salamander, Dicamptodon ensatus (Eschscholtz). Wasmann Collector 5: 141-142.

Kessel, E.L. and B.B. Kessel. 1943a. The rate of growth of older larvae of the Pacific giant salamander, Dicamptodon ensatus (Eschscholtz). Wasmann Collector 5: 141-142. Kessel, E.L. and B.B. Kessel. 1943b. The rate of growth of the young larvae of the Pacific Giant Salamander, Dicamptodon ensatus (Eschscholtz). Wasmann Collector 5: 108-111.

Kessel, E.L. and B.B. Kessel. 1943b. The rate of growth of the young larvae of the Pacific Giant Salamander, Dicamptodon ensatus (Eschscholtz). Wasmann Collector 5: 108-111. Kessel, E.L. and B.B. Kessel. 1944. Metamorphosis of the Pacific giant salamander, Dicamptodon ensatus (Eschscholtz). Wasmann Collector 6: 38-48.

Kessel, E.L. and B.B. Kessel. 1944. Metamorphosis of the Pacific giant salamander, Dicamptodon ensatus (Eschscholtz). Wasmann Collector 6: 38-48. Lind, A.J. and H.H. Welsh, Jr. 1990. Predation by Thamnophis couchii on Dicamptodon ensatus. Journal of Herpetology 24(1): 104-106.

Lind, A.J. and H.H. Welsh, Jr. 1990. Predation by Thamnophis couchii on Dicamptodon ensatus. Journal of Herpetology 24(1): 104-106. Maughan, O.E., M.G. Wickham, P. Laumeyer and R.L. Wallace. 1976. Records of the Pacific Giant Salamander, Dicamptodon ensatus, (Amphibia, Urodela, Ambystomatidae) from the Rocky Mountains in Idaho. Journal of Herpetology 10(3): 249-251.

Maughan, O.E., M.G. Wickham, P. Laumeyer and R.L. Wallace. 1976. Records of the Pacific Giant Salamander, Dicamptodon ensatus, (Amphibia, Urodela, Ambystomatidae) from the Rocky Mountains in Idaho. Journal of Herpetology 10(3): 249-251. Maxell, B.A. 2009. State-wide assessment of status, predicted distribution, and landscapelevel habitat suitability of amphibians and reptiles in Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Missoula, MT: Wildlife Biology Program, University of Montana. 294 p.

Maxell, B.A. 2009. State-wide assessment of status, predicted distribution, and landscapelevel habitat suitability of amphibians and reptiles in Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Missoula, MT: Wildlife Biology Program, University of Montana. 294 p. Nussbaum, R.A. 1972. Systematics of the salamander genus Dicamptodon Strauch (Amphibia: Caudata: Ambystomatidae). Ph.D. Dissertation. Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. 226 p.

Nussbaum, R.A. 1972. Systematics of the salamander genus Dicamptodon Strauch (Amphibia: Caudata: Ambystomatidae). Ph.D. Dissertation. Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. 226 p. Reed, C.A. 1949. The problem of metamorphosis in the western marbled salamander Dicamptodon ensatus. Copeia 1949: 81.

Reed, C.A. 1949. The problem of metamorphosis in the western marbled salamander Dicamptodon ensatus. Copeia 1949: 81. Thompson, L.S. 1982. Distribution of Montana amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. Bozeman: Montana Audubon Council. 24 pp.

Thompson, L.S. 1982. Distribution of Montana amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. Bozeman: Montana Audubon Council. 24 pp. Welsh, H.H., Jr. 1986a. Dicamptodon ensatus (Pacific Giant Salamander). Behavior. Herpetological Review 17(1): 19.

Welsh, H.H., Jr. 1986a. Dicamptodon ensatus (Pacific Giant Salamander). Behavior. Herpetological Review 17(1): 19. Welsh, H.H., Jr. 1986b. Life history notes. Caudata. Dicamptodon ensatus (Pacific giant salamander). Herpetological Review 17(1): 19.

Welsh, H.H., Jr. 1986b. Life history notes. Caudata. Dicamptodon ensatus (Pacific giant salamander). Herpetological Review 17(1): 19. Yarrow, H.C. 1882. Check list of North American reptilia and batrachia, with catalogue of specimens in the U.S. National Museum. United States National Museum Bulletin 24. 249 p.

Yarrow, H.C. 1882. Check list of North American reptilia and batrachia, with catalogue of specimens in the U.S. National Museum. United States National Museum Bulletin 24. 249 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Idaho Giant Salamander"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Amphibians"