View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Black-tailed Jackrabbit - Lepus californicus

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

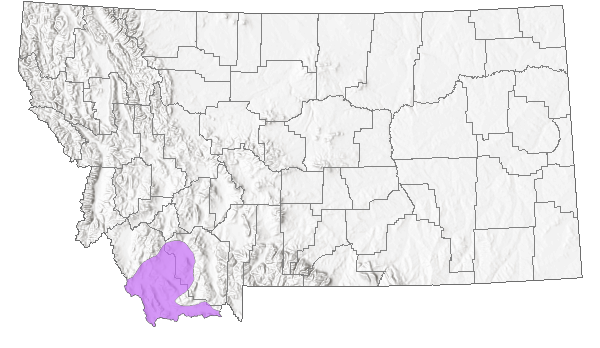

Species is found in a limited area of southwest Montana. It is very infrequently observed (last observation 2019) and additional data are needed to assess status.

General Description

The common name Black-tailed Jackrabbit is derived from the prominent black coloration on the dorsal surface of the tail (the ventral side is colored white). The Black-tailed Jackrabbit is a medium sized hare with exceptionally long ears and hind legs. The average weight of two male specimens from Montana was 2.0 kilograms; and 2.6 kilograms for four non-pregnant females (Foresman 2012b). Both males and females have a musky odor that originates from two rectal glands (Vorhies and Taylor 1933). The pelage is grayish-brown to grayish-black in coloration, and the black tail is quite distinct. Juveniles possess a darker coat that is replaced by the paler, adult pelage in six to nine months (Haskell and Reynolds 1947). An annual molt occurs in adults between late August and early October depending on latitude. The supraorbital process of the skull is pronounced, and both the rostrum and braincase are long and slender. The skull contains a total of 28 teeth and the dental formula is: I 2/1, C 0/0, P 3/2, M 3/3 (Best 1996).

Diagnostic Characteristics

The long ears and hind legs distinguish the Black-tailed Jackrabbit from the three species of Montana cottontails (Sylvilagus floridanus, S. audubonii, and S. nuttallii), as well as the Pygmy Rabbit (Brachylagus idahoensis) (Foresman 2012b). Both the White-tailed Jackrabbit (Lepus townsendii) and the Snowshoe Hare (Lepus americanus) lack the black coloration on the tail. Unlike these two members of the genus Lepus, Black-tailed Jackrabbits do not change pelage color in winter.

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Global Range

Estimated global breeding range area is: 4,961,417 km

2 (Approximately <1% in Montana)

See information about

iNaturalist Geomodels

iNaturalist Geomodels

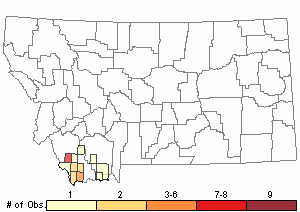

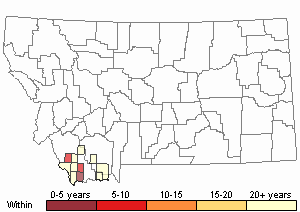

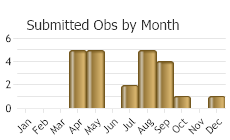

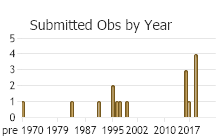

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 27

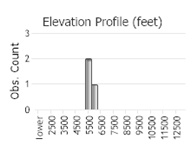

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

This species is considered non-migratory. No information is available on the daily movements and home ranges within the state of Montana. In Kansas, home ranges were reported to be between 20 and 140 hectares, and less than 16 hectares in Idaho (Harestad and Burnell 1979, Lechleitner 1959, Tiemeier 1965). Dispersal distances of up to 45 kilometers in 17 weeks have been reported.

Habitat

No information is available for Montana, however, in other portions of its range the Black-tailed Jackrabbit is known to occupy a small range of habitats, including open plains, fields, and deserts (Caire et al. 1989). In the United States it has often been reported that populations increase with heavy cattle grazing (Taylor and Lay 1944, Tiemeier 1965), and in Mexico the species occupies desert habitats and grasslands that have been grazed almost to bare ground (Leopold 1959). A single study from Colorado indicated that the species preferred light to moderate grazing (Flinders and Hansen 1975), but in all cases, Black-tailed Jackrabbits are associated with open country with scattered shrubs or cacti for cover. The species is known to occur at elevations ranging from 84 meters below to 3,750 meters above sea level (Best 1996).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Shrubland

Foothills - Montane Shrubland

Sagebrush Shrubland

Grassland

Lowland - Prairie Grassland

Human Land Use

Agriculture

Developed

Food Habits

No information specific to Montana is available. Based upon general information, these lagomorphs are known to forage on herbaceous vegetation such as grasses and forbs during the spring and summer, but switch to the buds, bark, and leaves of woody plants in the fall and winter (Foresman 2012). Water is obtained through consumed vegetation; an individual's diet is 68% water at minimum (Nagy et al. 1976). Because the diet of Black-tailed Jackrabbits is often low in nutrients, additional water, protein, and vitamins have to be obtained through coprophagy - the consumption of fecal pellets (Steigers et al. 1982, Foresman 2012). Young are known to consume the pellets of their mother. These soft pellets are produced while resting during the day, swallowed whole, and re-digested. An adult can consume as much as 390 grams of forage each day (Johnson and Peek 1984) and will produce, on average, 545 pellets (Arnold and Reynolds 1943).

Ecology

Black-tailed Jackrabbits are sympatric with Lepus townsendii in Beaverhead County (Hoffmann and Pattie 1968). They are true hares with precocial young. They are considered both a "desirable" (food, recreation) and "undesirable" (crop damage, competition with livestock) species (Dunn et al. 1982).

As with other species of rabbits and hares, L. californicus populations are known to fluctuate markedly, with alternating periods of local population increases and declines. Although these cycles can be rather dramatic, they appear to be considerably lower in magnitude than the frequently cited example of the Snowshoe Hares (L. americanus) (Gross et al. 1974). It is not likely that individuals in the wild survive more than seven years.

During the day, individuals rest in shallow depressions under vegetation called forms (Best 1996). These structures measure 10 to 20 centimeters in width, 30 to 45 centimeters in length, and 3 to 11 centimeters in depth. Both pre-existing forms as well as those excavated by individuals are commonly used, and adults will rarely enter burrows for shelter. Black-tailed Jackrabbits are mostly solitary, but occasionally form small groups at good foraging sites (Foresman 2012a). Aggressive behavior is uncommon, but males are known to "box" with one another (Hoffmeister 1986). This behavior, characterized by standing up on the hind legs and hitting with the forelimbs, along with ear biting is the most aggressive form of social behavior, but individuals are also known to butt heads and chase each other short distances (Tiemeier 1965).

The characteristic long ears of the species demonstrate geographical variation in size occurring according to Allen's Rule (Griffing 1974). This general 'rule' predicts that external appendages such as ears will be enlarged in warmer climates to facilitate radiation of heat back into the air. The ears of L. californicus, on average, are larger in warmer climates than the ears of populations of L. californicus here in Montana.

L. californicus is well suited for a jumping style of locomotion. Individuals casually will move at a rate of 1.5 to 3 meters per jump, but can cover up to 10 meters when disturbed (Foresman 2012). L. californicus can move at speeds of up to 56 kilometers per hour and jump as high as 1.5 meters.

Individuals may be host to a large number of diseases or disease carrying microorganisms such as Borrelia burgdorferi, Toxoplasma gondii, Coxiella burnetti, Paturella tularensis, Pasturella pestis, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, and others (Best 1996). Adult mortality in Idaho was reported to be as high as 87% during the breeding season and as high as 67% during the remainder of the year (Gross et al. 1974). Years of population increase saw yearly mortality rates as low 64%, and years of population decrease had rates as high as 90%.

Reproductive Characteristics

There is no information available specific to the state of Montana. Information gathered in other areas of the species' range suggests that breeding among Black-tailed Jackrabbits is promiscuous. Receptive females will often copulate with the first interested male after a lengthy courtship behavior (Haskell and Reynolds 1947). This process, which can last from 5 to 20 minutes, consists of circling, chasing, jumping, and urinating, almost always followed by copulation, which often occurs more than once.

Nests are thickly lined with fur and entered through a small opening at the surface. Where the topsoil is hard, nests are no more than excavated forms beneath clumps of grass or brush (Vorhies and Taylor 1933). Local populations of L. californicus have synchronized copulation periods within each breeding season (Gross et al. 1974). Copulation is followed by ovulation and a gestation period of approximately 40 days. Young are born weighing approximately 66 grams with a complete set of teeth, coat of fur, and open eyes (Haskell and Reynolds 1947). By the third day after birth the young exhibit 'considerable coordination', and begin digging on the fourth day.

The duration of the breeding season and the size of each litter vary with geographic location (Gross et al. 1974). In northern Utah, where the breeding season consists of 190 days (enough time for four to five litters), the average litter size was 3.8. In contrast, in southern Arizona, where the breeding season lasts 300 days (enough time for seven separate litters), the average litter size was 2.24. Thus, breeding Black-tailed Jackrabbits in more northern climates compensate shortened breeding seasons with larger litter sizes. Breeding pairs within local populations show a considerable amount of synchronicity, beginning each copulation period at almost the same time.

Management

No special management activities have been developed or implemented for this species in Montana.

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Arnold, J.F., and H.G. Reynolds. 1943. Droppings of Arizona and antelope jackrabbits and the ¿pellet census.¿ The Journal of Wildlife Management 39:152-156.

Arnold, J.F., and H.G. Reynolds. 1943. Droppings of Arizona and antelope jackrabbits and the ¿pellet census.¿ The Journal of Wildlife Management 39:152-156. Best, T.L. 1996. (Lepus californicus). American Society of Mammalogists, Lawrence, KS. Mammalian Species No. 530:1-10.

Best, T.L. 1996. (Lepus californicus). American Society of Mammalogists, Lawrence, KS. Mammalian Species No. 530:1-10. Caire, W., J.D. Tyler, and B.P Glass. 1989. Mammals of Oklahoma. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. xiii + 567 pp.

Caire, W., J.D. Tyler, and B.P Glass. 1989. Mammals of Oklahoma. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. xiii + 567 pp. Dunn, J.P., J.A. Chapman, and R.E. Marsh. 1982. Jackrabbits: (Lepus californicus) and allies. Pages 124-145 in J. A. Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer, editors. Wild mammals of North America: biology, management, and economics. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Dunn, J.P., J.A. Chapman, and R.E. Marsh. 1982. Jackrabbits: (Lepus californicus) and allies. Pages 124-145 in J. A. Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer, editors. Wild mammals of North America: biology, management, and economics. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. Flinders, J.T. and R.M. Hansen. 1975. Spring population responses of cottontails and jackrabbits to cattle grazing shortgrass prairie. Journal of Range Management 28(4):290-293.

Flinders, J.T. and R.M. Hansen. 1975. Spring population responses of cottontails and jackrabbits to cattle grazing shortgrass prairie. Journal of Range Management 28(4):290-293. Foresman, K.R. 2012. Mammals of Montana. Second edition. Mountain Press Publishing, Missoula, Montana. 429 pp.

Foresman, K.R. 2012. Mammals of Montana. Second edition. Mountain Press Publishing, Missoula, Montana. 429 pp. Griffing,, J.P. 1974. Body measurements of the black-tailed jackrabbits of southeastern New Mexico with implications of Allen's Rule. Journal of Mammalogy 55:674-678.

Griffing,, J.P. 1974. Body measurements of the black-tailed jackrabbits of southeastern New Mexico with implications of Allen's Rule. Journal of Mammalogy 55:674-678. Gross, J.E., L.C. Stoddart, and F.H. Wagner. 1974. Demographic analysis of a northern Utah jackrabbit population. Wild. Mono. No. 40. The Wildlife Society, Inc. 72 pp.

Gross, J.E., L.C. Stoddart, and F.H. Wagner. 1974. Demographic analysis of a northern Utah jackrabbit population. Wild. Mono. No. 40. The Wildlife Society, Inc. 72 pp. Harestad, A.S. and F.L. Bunnell. 1979. Home range and body weight - a reevaluation. Ecology 60:389-402.

Harestad, A.S. and F.L. Bunnell. 1979. Home range and body weight - a reevaluation. Ecology 60:389-402. Haskell, H.S., and H.G. Reynolds. 1947. Growth, developmental food requirements, and breeding activity of the California jack rabbit. Journal of Mammalogy 28:129-136.

Haskell, H.S., and H.G. Reynolds. 1947. Growth, developmental food requirements, and breeding activity of the California jack rabbit. Journal of Mammalogy 28:129-136. Hoffmann, R.S. and D.L. Pattie. 1968. A guide to Montana mammals: identification, habitat, distribution, and abundance. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 133 p.

Hoffmann, R.S. and D.L. Pattie. 1968. A guide to Montana mammals: identification, habitat, distribution, and abundance. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 133 p. Hoffmeister, D.F. 1986. Mammals of Arizona. Univ. Arizona Press and Arizona Game and Fish Dept. 602 pp.

Hoffmeister, D.F. 1986. Mammals of Arizona. Univ. Arizona Press and Arizona Game and Fish Dept. 602 pp. Johnson, D.R., and J.M. Peek. 1984. The black-tailed jackrabbit in Idaho: life history, population dynamics, and control. University of Idaho, College of Agriculture Cooperative Extension Service Bulletin 637:1-6.

Johnson, D.R., and J.M. Peek. 1984. The black-tailed jackrabbit in Idaho: life history, population dynamics, and control. University of Idaho, College of Agriculture Cooperative Extension Service Bulletin 637:1-6. Lechleitner, R. R., February, 1959, Sex Ratio, Age Classes and Reproduction of the Black-tailed Jack Rabbit

Lechleitner, R. R., February, 1959, Sex Ratio, Age Classes and Reproduction of the Black-tailed Jack Rabbit Leopold, A.S. 1959. Wildlife of Mexico. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Leopold, A.S. 1959. Wildlife of Mexico. University of California Press, Berkeley. Nagy, K.A., V.H. Shoemaker, and W.R. Costa. 1976. water, electrolyte, and nitrogen budgets in jackrabbits (Lepus californicus) in the Mojave Desert. Physiological Zoology 49: 351-363.

Nagy, K.A., V.H. Shoemaker, and W.R. Costa. 1976. water, electrolyte, and nitrogen budgets in jackrabbits (Lepus californicus) in the Mojave Desert. Physiological Zoology 49: 351-363. Steigers, W.D., Jr., J.T. Flinders, and S.M. White. 1982. Rhythm of fecal production and protein content for black-tailed jackrabbits. The Great Basin Naturalist 42:567-571

Steigers, W.D., Jr., J.T. Flinders, and S.M. White. 1982. Rhythm of fecal production and protein content for black-tailed jackrabbits. The Great Basin Naturalist 42:567-571 Taylor, W.P., and D.W. Lay. 1944. Ecological niches occupied by rabbits in eastern Texas. Ecology 25: 120-121.

Taylor, W.P., and D.W. Lay. 1944. Ecological niches occupied by rabbits in eastern Texas. Ecology 25: 120-121. Tiemeier, O.W. 1965. Bionomics. P. 5-37. In: The black-tailed jackrabbit in Kansas. Kansas State Univ. Agr. Exp. Sta. Tech. Bull. 140.

Tiemeier, O.W. 1965. Bionomics. P. 5-37. In: The black-tailed jackrabbit in Kansas. Kansas State Univ. Agr. Exp. Sta. Tech. Bull. 140. Vorhies, C.T., and W.P. Taylor. 1933. The life histories and ecology of jack rabbits, (Lepus alleni) and (Lepus californicus ssp)., in relation to grazing in Arizona. University of Arizona, College of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station, Technical Bulletin 49:471-587.

Vorhies, C.T., and W.P. Taylor. 1933. The life histories and ecology of jack rabbits, (Lepus alleni) and (Lepus californicus ssp)., in relation to grazing in Arizona. University of Arizona, College of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station, Technical Bulletin 49:471-587.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Chapman, J.A., and G.A. Feldhamer. 1982. Wild mammals of North America: biology, management, and economics. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Chapman, J.A., and G.A. Feldhamer. 1982. Wild mammals of North America: biology, management, and economics. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland. Flinders, J.T. and R.M. Hansen. 1973. Abundance and dispersion of Leoprids within a shortgrass ecosystem. Journal of Mammalogy. 54(1): 287-29.

Flinders, J.T. and R.M. Hansen. 1973. Abundance and dispersion of Leoprids within a shortgrass ecosystem. Journal of Mammalogy. 54(1): 287-29. Foresman, K. R. 2001. Key to the mammals of Montana. University of Montana Bookstore, Missoula, Montana. 92 pp.

Foresman, K. R. 2001. Key to the mammals of Montana. University of Montana Bookstore, Missoula, Montana. 92 pp. Foresman, K.R. 2001. The wild mammals of Montana. American Society of Mammalogists, Special Publication Number 12. Lawrence, KS. 278 pp.

Foresman, K.R. 2001. The wild mammals of Montana. American Society of Mammalogists, Special Publication Number 12. Lawrence, KS. 278 pp. Giddings, B.J. 1986. Ecology of the bobcat in a prairie rangeland-agricultural environment in eastern Montana: home range, size, movements, and habitat use of bobcats in a prairie rangeland environment. MS Thesis. Montana State University. Bozeman, Montana.

Giddings, B.J. 1986. Ecology of the bobcat in a prairie rangeland-agricultural environment in eastern Montana: home range, size, movements, and habitat use of bobcats in a prairie rangeland environment. MS Thesis. Montana State University. Bozeman, Montana. Hall, E.R. 1981. The mammals of North America, volumes I and II. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. 1181 pp.

Hall, E.R. 1981. The mammals of North America, volumes I and II. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. 1181 pp. Hendricks, P. and M. Roedel. 2001. A faunal survey of the Centennial Valley Sandhills, Beaverhead County, Montana. Report to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 44 p.

Hendricks, P. and M. Roedel. 2001. A faunal survey of the Centennial Valley Sandhills, Beaverhead County, Montana. Report to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 44 p. Hoffmann, R.S., P.L. Wright, and F.E. Newby. 1969. The distribution of some mammals in Montana. I. Mammals other than bats. Journal of Mammalogy 50(3): 579-604.

Hoffmann, R.S., P.L. Wright, and F.E. Newby. 1969. The distribution of some mammals in Montana. I. Mammals other than bats. Journal of Mammalogy 50(3): 579-604. Johnson, M.K. and R.M. Hansen. 1979. Foods of cottontails and woodrats in southcentral Idaho. Journal of Mammalogy. 60(1): 213-215.

Johnson, M.K. and R.M. Hansen. 1979. Foods of cottontails and woodrats in southcentral Idaho. Journal of Mammalogy. 60(1): 213-215. Jones, J.K., D.M. Armstrong, R.S. Hoffmann and C. Jones. 1983. Mammals of the northern Great Plains. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. 379 pp.

Jones, J.K., D.M. Armstrong, R.S. Hoffmann and C. Jones. 1983. Mammals of the northern Great Plains. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. 379 pp. Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. MacCracken, J. G, and R. M. Hansen. 1982. Herbaceous vegetation ofhabitat used by Blacktail Jackrabbits and Nuttall Cottontails in southeastern Idaho. American Midland Naturalist 107:180-184.

MacCracken, J. G, and R. M. Hansen. 1982. Herbaceous vegetation ofhabitat used by Blacktail Jackrabbits and Nuttall Cottontails in southeastern Idaho. American Midland Naturalist 107:180-184. Reid, F. 2006. Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America, 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston and New York, 608 pp.

Reid, F. 2006. Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America, 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston and New York, 608 pp. Smith, G.W. 1990. Home range and activity patterns of black-tailed jackrabbits. Great Basin Nat. 50:249-256.

Smith, G.W. 1990. Home range and activity patterns of black-tailed jackrabbits. Great Basin Nat. 50:249-256. Vorhies, C. T. 1945. Water requirements of desert animals in the southwest. University of Arizona, Agricultural Experiment Station, Technical Bulletin, 107:485-525.

Vorhies, C. T. 1945. Water requirements of desert animals in the southwest. University of Arizona, Agricultural Experiment Station, Technical Bulletin, 107:485-525. Wilson, D. E., and D. M. Reeder (editors). 1993. Mammal Species of the World: a Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Second Edition. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC. xviii + 1206 pp.

Wilson, D. E., and D. M. Reeder (editors). 1993. Mammal Species of the World: a Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Second Edition. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC. xviii + 1206 pp.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Black-tailed Jackrabbit"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Mammals"