View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

New Zealand Mudsnail - Potamopyrgus antipodarum

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

A conservation status rank is not applicable because this species is not a suitable target for conservation activities as a result of being exotic or introduced.

General Description

New Zealand Mudsnail (NZMS) is a small snail (4-6 mm) with a dextral (right-handed coiling), elongated shell with 5-6 whorls separated by deep grooves. It is generally dark brown to grey in color. This is an introduced species to MT with a stable or expanding distribution in the Missouri, Madison, Yellowstone, and Bighorn Rivers. It is not known in Montana west of the continental divide. In Montana this species was first discovered in the Madison River above Hebgen Reservoir in 1995 (Gustafson pers. comm.). However, the very large population present at that time indicataes that the introduction was a few years earlier. It is a native of New Zealand, but long established in Australia and Europe. This species has been known in North America since 1987 in the Snake River basin of Idaho

Diagnostic Characteristics

Taxonomically, New Zealand mud snails are in the snail family Hydrobiidae. Hydrobiids can be distinguished from other aquatic snail families by having dextral (opening to the right with the spire pointing away from you) shells with an operculum (a hard calcareous flat that can seal the opening of the shell). New Zealand mud snails are small (~ 2-6 mm) and generally dark colored

Range Comments

Native Range: The freshwater streams and lakes of New Zealand and adjacent small islands; it is naturalized in Australia and Europe (Hall et al. 2003).

Global Range: (>2,500,000 square km (greater than 1,000,000 square miles)) Introduced to Europe in the 1800's where it is now widespread. Introduced into the Snake River system (Idaho) in North America (first appeared in 1987). Since then it has spread, from a second introduction to nearly a dozen sites in Lake Ontario (Zaranko et al., 1997). Kerans et al. (2005) list it from Idaho, Great Lakes, California, Colorado, Wyoming and Montana.

The NZMS was first discovered in the middle portion of the Snake River in Idaho in 1987. By 1995, the mudsnail had reached the Madison River in Montana, and into Yellowstone National Park the following year (Wyoming). It is also established in Minidoka National Wildlife Refuge, Idaho (USFWS 2005). Populations were discovered near the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon in 1997, and the Owens River in California. Since then, this species is becoming very widespread in California. This species became established in the lower Columbia River, Washington about 1999 (M. Sytsma, pers. comm.) and in the Colorado River in northern Arizona by 2002 and continues to spread (Cross et al 2010). In Utah, the first mudsnails were found about 2001 and have since been found in the Green River and many others. In 2004, mudsnails were found in small Colorado creek near Boulder (P. Walker, pers. comm.).

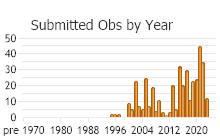

Since the peak NZMS densities in Montana were reported in the early 2000's, Missouri and Madison River populations have declined over the last decade, but are more recently building their populations back, especially below Holter and Hebgen Reservoirs, respectively (McGuire 2016, Stagliano 2017).

For maps and other distributional information on non-native species see:

Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Habitat Tool (INHABIT) from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Compendium from the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI)

EDDMapS Species Information EDDMapS Species Information

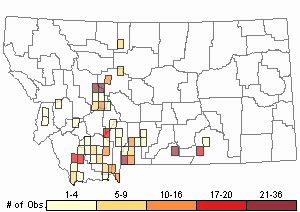

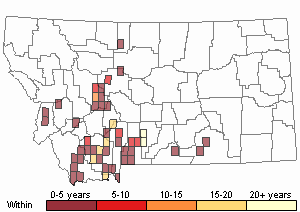

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

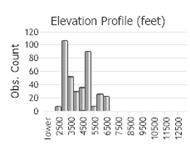

Number of Observations: 423

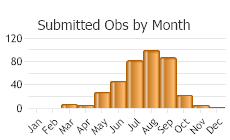

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

Potamopyrgus antipodarum can survive passage through the guts of fish and may be transported by these animals (Bruce 2006). Throughout Montana, it has been transported to different waterbodies on the felt soles of fishermen’s wading boots (ANS 2007). It can also float by itself or on mats of Cladophora spp., and move 60 m upstream in 3 months through positive rheotactic behavior (Zaranko et al. 1997). It can respond to chemical stimuli in the water, including the odor of predatory fish, which causes it to migrate to the undersides of rocks to avoid predation (Levri 1998).

Means of Introduction or Expansion: 1) Fish hatcheries and associated stocking operations, 2) Recreational watercraft and trailers, 3) Recreational water users: Particularly when embedded in mud or attached to plant debris, NZ mudsnails may be transported on fishing gear, on waders and boots, swimsuits and swimming toys and even by hunting dogs and horses, 4) Sand/gravel mining, extraction, and dredging: Any waterway operations that remove and transport mud, sand, and other bottom materials from areas with NZ mudsnails can serve as a vector for new introductions, 5) Aquatic plant trade and collections (ANS 2007). Potamopyrgus antipodarum was most likely introduced to the Great Lakes in ships from Europe, where there are nonindigenous populations (Levri et al. 2007, Zaranko et al. 1997) or in the water of live gamefish shipped from infested waters to western rivers in the United States.

Habitat

New Zealand mud snails appear to prefer flowing water habitats with stable flows. Springs, spring creeks, and river sections downstream from dams are all places that they thrive in. They can survive in cool lakes with suitable habitat. They are most typically found on larger cobble substrates or on pieces of wood.

Food Habits

The NZMS is a nocturnal grazer, feeding on plant and animal detritus, epiphytic and periphytic algae, sediments and diatoms largely on cobbles or submerged woody debris.

Ecology

The NZMS is a nocturnal grazer, feeding on plant and animal detritus, epiphytic and periphytic algae, sediments and diatoms (Zaranko et al. 1997, USGS 2017).

The snail tolerates siltation, thrives in disturbed watersheds, and benefits from high nutrient flows allowing for filamentous green algae growth. It occurs amongst macrophytes and prefers littoral zones in lakes or slow streams with silt and organic matter substrates, but tolerates high flow environments where it can burrow into the sediment (Collier et al. 1998, Death et al. 2003, Holomuzki and Biggs 2000, Richards et al. 2001, Zaranko et al. 1997).

Reproductive Characteristics

Potamopyrgus antipodarum is ovoviviparous and parthenogenic. Native populations in New Zealand consist of diploid sexual and triploid parthenogenically cloned females, as well as sexually functional males (less than 5% of the total population). One snail produces approximately 230 young per year. Reproduction occurs in spring and summer, and the life cycle is annual (Gerard et al. 2003, Hall et al. 2003). All introduced populations in North America are clonal, consisting of genetically identical females.

Management

NZMS have great potential for wide-spread colonization because they have a broad environmental tolerance. Although the species occurs in a wide range of aquatic habitat types, including diverse ranges of temperature, osmotic concentrations, flows, substrates and disturbance regimes, clonal lineages may have either narrow or broad ecological tolerances. Likely to find all shallower waters (<50 m depth) as suitable habitat. High spread potential (USEPA 2008). Abundant populations of introduced P. antipodarum may outcompete other grazers and inhibit colonization by other macroinvertebrates (Kerans et al. 2005).

Many times a newly discovered population of NZ mudsnails may be in a river or lake where chemical eradication will not be feasible and physical eradication difficult. This would be the case with large rivers or lakes where it is impossible to isolate the invader and treatment would be difficult to contain. In other situations the invader may occupy too large an area or other ecological or political restraints may rule. Areas where eradication may be possible include small lakes and ponds, waterbodies that can be temporarily hydrologically separated (e.g., curtain, wall), irrigation canals, and fish hatcheries.

Contact information for Aquatic Invasive Species personnel:Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks Aquatic Invasive Species staffMontana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation's Aquatic Invasive Species Grant ProgramMontana Invasive Species Council (MISC)Upper Columbia Conservation Commission (UC3)Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Threats to the NZMS are minimal, other than reservoir drawdowns and river dewatering which will leave the snails prone to desiccation. Although a discrepancy exists when comparing temperature tolerance limits of North American and New Zealand populations. North American populations are generally adapted to warmer temperature regimes than their New Zealand counterparts.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication ANS Task Force. 2007. National Management and Control Plan for the New Zealand Mudsnail. Prepared for the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force by the New Zealand Mudsnail Management and Control Plan Working Group.

ANS Task Force. 2007. National Management and Control Plan for the New Zealand Mudsnail. Prepared for the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force by the New Zealand Mudsnail Management and Control Plan Working Group. Bruce, R.L. 2006. Methods of fish depuration to control New Zealand mudsnails at fish hatcheries. Masters Thesis, University of Idaho, 87 pp.

Bruce, R.L. 2006. Methods of fish depuration to control New Zealand mudsnails at fish hatcheries. Masters Thesis, University of Idaho, 87 pp. Collier, K. J., R.J. Wilcock, and A.S. Meredith. 1998. Influence of substrate type and physico-chemical conditions on macroinvertebrate faunas and biotic indices of some lowland Waikato, New Zealand, streams. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 32:1-19.

Collier, K. J., R.J. Wilcock, and A.S. Meredith. 1998. Influence of substrate type and physico-chemical conditions on macroinvertebrate faunas and biotic indices of some lowland Waikato, New Zealand, streams. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 32:1-19. Cross, W.F., E.J. Rosi-Marshall, K.E. Behn, T.A. Kennedy, R.O. Hall Jr., A.E. Fuller, and C.V. Baxter. 2010. Invasion and production of New Zealand mudsnails in the Colorado River, Glen Canyon. Biological Invasions 12: 3033-3043.

Cross, W.F., E.J. Rosi-Marshall, K.E. Behn, T.A. Kennedy, R.O. Hall Jr., A.E. Fuller, and C.V. Baxter. 2010. Invasion and production of New Zealand mudsnails in the Colorado River, Glen Canyon. Biological Invasions 12: 3033-3043. Death, R.G., B. Baillie, and P. Fransen. 2003. Effect of Pinus radiata logging on stream invertebrate communities in Hawke's Bay, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 37(3):507–520

Death, R.G., B. Baillie, and P. Fransen. 2003. Effect of Pinus radiata logging on stream invertebrate communities in Hawke's Bay, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 37(3):507–520 Gerard, C., A. Blanc, and K. Costil. 2003. Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Mollusca: Hydrobiidae) in continental aquatic gastropod communities: impact of salinity and trematode parasitism. Hydrobiologia 493(1–3):167–172.

Gerard, C., A. Blanc, and K. Costil. 2003. Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Mollusca: Hydrobiidae) in continental aquatic gastropod communities: impact of salinity and trematode parasitism. Hydrobiologia 493(1–3):167–172. Gustafson, Dan. 2001. Personal communication: Dan Gustafson, Research Scientist Department of Biology Montana State University.

Gustafson, Dan. 2001. Personal communication: Dan Gustafson, Research Scientist Department of Biology Montana State University. Hall, R.O., Jr., J.L. Tank, and M.F. Dybdahl. 2003. Exotic snails dominate nitrogen and carbon cycling in a highly productive stream. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 1(8):407–411.

Hall, R.O., Jr., J.L. Tank, and M.F. Dybdahl. 2003. Exotic snails dominate nitrogen and carbon cycling in a highly productive stream. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 1(8):407–411. Holomuzki, J.R., and B.J.F. Biggs. 2006. Habitat–specific variation and performance trade–offs in shell armature of New Zealand mudsnails. Ecology 87(4):1038–1047.

Holomuzki, J.R., and B.J.F. Biggs. 2006. Habitat–specific variation and performance trade–offs in shell armature of New Zealand mudsnails. Ecology 87(4):1038–1047. Kerans, B.L., M.F. Dybdahl, M.M. Gangloff, and J.E. Jannot. 2005. Potamopyrgus antipodarum: distribution, density, and effects on native macroinvertebrate assemblages in the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 24(1): 123-138.

Kerans, B.L., M.F. Dybdahl, M.M. Gangloff, and J.E. Jannot. 2005. Potamopyrgus antipodarum: distribution, density, and effects on native macroinvertebrate assemblages in the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 24(1): 123-138. Levri, E.P. 1998. Perceived predation risk, parasitism, and the foraging behavior of a freshwater snail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum). Canadian Journal of Zoology 76(10):1878–1884.

Levri, E.P. 1998. Perceived predation risk, parasitism, and the foraging behavior of a freshwater snail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum). Canadian Journal of Zoology 76(10):1878–1884. Levri, E.P., A.A. Kelly, and E. Love. 2007. The invasive New Zealand mud snail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum) in Lake Erie. Journal of Great Lakes Research 33: 1–6.

Levri, E.P., A.A. Kelly, and E. Love. 2007. The invasive New Zealand mud snail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum) in Lake Erie. Journal of Great Lakes Research 33: 1–6. McGuire, D.L. 2016. Madison and Missouri River Macroinvertebrate Biomonitoring: 2015 Data Summary. Report to Northwestern Energy Montana.

McGuire, D.L. 2016. Madison and Missouri River Macroinvertebrate Biomonitoring: 2015 Data Summary. Report to Northwestern Energy Montana. Richards, D.C., L.D. Cazier, and G.T. Lester. 2001. Spatial distribution of three snail species, including the invader Potamopyrgus antipodarum, in a freshwater spring. Western North American Naturalist 61(3):375–380.

Richards, D.C., L.D. Cazier, and G.T. Lester. 2001. Spatial distribution of three snail species, including the invader Potamopyrgus antipodarum, in a freshwater spring. Western North American Naturalist 61(3):375–380. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 2008. EPA Monitoring Data. EPA Great Lakes National Program Office.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 2008. EPA Monitoring Data. EPA Great Lakes National Program Office. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 2005. National Wildlife Refuge System Invasive Species. https://www.fws.gov/invasives/nwrs.html (Last accessed 2006).

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 2005. National Wildlife Refuge System Invasive Species. https://www.fws.gov/invasives/nwrs.html (Last accessed 2006). United States Geological Survey (USGS). 2003. US Fish and Wildlife Service National Wildlife Refuge System: Invasive Species Survey Information.

United States Geological Survey (USGS). 2003. US Fish and Wildlife Service National Wildlife Refuge System: Invasive Species Survey Information. Zaranko, D.T., D.G. Farara, and F.G. Thompson. 1997. Another exotic mollusc in the Laurentian Great Lakes: the New Zealand native Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray 1843) (Gastropoda, Hydroibiidae). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science, 54: 809-814.

Zaranko, D.T., D.G. Farara, and F.G. Thompson. 1997. Another exotic mollusc in the Laurentian Great Lakes: the New Zealand native Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray 1843) (Gastropoda, Hydroibiidae). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science, 54: 809-814.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Richards, D.C. 2004. Competition between the threatened Bliss Rapids Snail, Taylorconcha serpenticola (Hershler et al.) and the invasive, aquatic Snail, Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray). Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 156 p.

Richards, D.C. 2004. Competition between the threatened Bliss Rapids Snail, Taylorconcha serpenticola (Hershler et al.) and the invasive, aquatic Snail, Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray). Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 156 p. Richards, D.C., P. O'Connell, and D.C. Shinn. 2004. Simple control method to limit the spread of the New Zealand mudsnail Potamopyrgus antipodarum. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 24:114-117.

Richards, D.C., P. O'Connell, and D.C. Shinn. 2004. Simple control method to limit the spread of the New Zealand mudsnail Potamopyrgus antipodarum. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 24:114-117. Richins, Eric H. 2016. Community perturbation associated with New Zealand Mudsnail (Potamapyrgus antipodarum) invasion: Discrepancies in temporal and spatial assessment. M.S. Thesis. University of Montana. Missoula, MT.

Richins, Eric H. 2016. Community perturbation associated with New Zealand Mudsnail (Potamapyrgus antipodarum) invasion: Discrepancies in temporal and spatial assessment. M.S. Thesis. University of Montana. Missoula, MT.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "New Zealand Mudsnail"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Snails / Slugs"