View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Four-spotted Tree Cricket - Oecanthus quadripunctatus

General Description

Preface to the Genus Oecanthus The following is taken from Fulton (1915, June 1926), Walker (1962), and Funk (1982). Species in this genus are divided into 4 natural groups based on their morphology, color and habits. These groups are

niveus,

releyi,

nigricornus, and

varicornis. Only two groups occur in Montana, with 4 species in the

nigricornus group and one species,

Snowy Tree Cricket (

O. fultoni), in the

releyi group.

Generally, tree crickets are characterized by their long, slender shape, pale colors and arboreal habits. The tegmina (forewings) of males are broad and flat, and female wings are long and narrow and wrapped closely to the body. Their legs are very slender, armed with two rows of minute teeth interspersed with a number of delicate spines. The tarsi (feet) are three-segmented with the second segment being small and compressed. The antennae are longer than the body, filiform and often ornamented with distinctive black markings. The first two basal antennal segments are distinctively marked with spots, which are a convenient diagnostic character for species identification (see illustrations for each species).

The following comes from Fulton (1915, June and October 1926), Hebard (1928), Walker (1963), Helfer (1971), Capinera and Sechrist (1982), Vickery and Kevan (1985), Capinera et al. (2004), Himmelman (2009), and Scott (2010). This is a very slender-bodied tree cricket that is basically uniformly pale green. Some individuals may have a pale orange wash on the top of the head and/or a few black spots on the hind femur. The wings (tegmina) are translucent with a pale green wash. The antennae are usually a light grayish.

Song production in OecanthusSong is produced only by males, which raise their forewings (tegmina) perpendicular to the body and vibrate them in a transverse direction, so that the overlapping inner portions rub against each other. The sound-producing mechanism is located near the base of the wings. It is a broad expanded distal area which serves as a resonator to increase sound volume. A short prominent transverse vein occurs beneath forming a rasp-like structure about 1-1.5 mm wide with 20-50+ short teeth, depending upon the species, inclined toward the opposite wing. The number of teeth is a diagnostic feature. The right wing, termed the file, bears a series of downward projecting teeth, overlaps the left, termed the scraper. When the tegmina are raised and alternately opened and closed, the song is produced only on the closing stroke. Due to this partial wing-motion cycle, cricket songs are constructed of sound pulses. If a cricket opens and closes its wings many times in succession, it produces a trill. If the wings are opened and closed a few times, pauses, and repeats the song again, it produces a chirp. Songs vary according to ambient temperatures and is distinctive by sound analysis between species.

The Four-spotted Tree Cricket sings day and night and tends to be more diurnal than other species of

Oecanthus. Its song has been described as a rich, high, somewhat raspy continuous trill. In late afternoon, where populations are numerous, individuals will synchronize their singing into an almost deafening chorus which often lasts throughout the night. Song of this species is similar to that of the

Black-horned Tree Cricket (

O. nigrocornis), which often shares the same habitat (Fulton 1915, Elliott and Hershberger 2007, and Himmelman 2009).

Phenology

The Four-spotted Tree Cricket overwinters in the egg stage. Adults occur from late July or early August to the first autumn frost (Vickery and Kevan 1985).

Diagnostic Characteristics

The following is taken from Fulton (1915, June and October 1926), Hebard (1928), Walker (1963), Helfer (1971), Capinera and Sechrist (1982), Vickery and Kevan (1985), Capinera et al. (2004), Himmelman (2009), and Scott (2010). The body length for both male and female is 15-16 mm. Male stridulatory file is 1-2 mm possessing 50-67 teeth with an average of ±58. The first antennal segment normally has a vertical black spot with a separated oval or circular spot dorso-ventrally, and the second antennal segment possesses two separated vertical black spots, one long, one short. This character giving rise to the common name Four-spotted Tree Cricket. There are, however, variations with only one spot per segment (see illustration).

All Oecanthus species are similar in general form, appearance and behavior as noted above.

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

This species occurs in all conterminous U.S. states and into the southern edges of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec. O. quadripunctatus is the most common and widely distributed tree cricket species in North America. In Montana, it is reported for 21 counties, but probably occurs throughout the state (Vickery and Kevan 1985, Scott 2010, and Walker 2020).

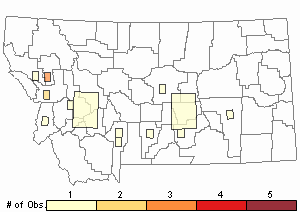

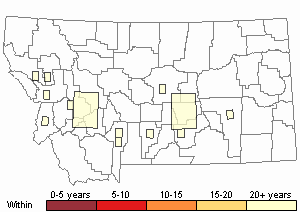

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 18

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Inhabits low growing brambles, weeds and other herbaceous plants along fencerows, abandoned fields, meadows, prairies, gardens, roadsides and alfalfa fields (Vickery and Kevan 1985, and Himmelman 2009).

Food Habits

The food habits of all the Oecanthus species consists of a great variety of both plant and animal origin, but the food items must be soft enough to be masticated by their weak jaws. One of their dietary mainstays is aphids. They also consume plant material by chewing holes in leaves, outer tissue of stems, the anthers of some plant flowers, chew holes in ripe fruit (apples, peaches, plums, etc.) to feed on the inner pulp, and eat fruiting bodies of fungi. The Prairie Tree Cricket favors gumweed, Grindelia sp. (Fulton June 1926, Vickery and Kevan 1985, and Himmelman 2009).

Reproductive Characteristics

Reproduction in OecanthusThe following is taken from Fulton (1915, June 1926), Walker (1962), and Funk (1982). The mating and reproduction habits of all

Oecanthus species are generally similar in behavior and complexity. When a female is attracted to a singing male, she approaches him from the rear because that is direction most of the sound travels and amplified by his wings. When the male senses the female’s approach, he stops singing, turns around and touches her with his antennae. It is thought that this “tasting” of her confirms she is the same species and an appropriate mate. The next step in the courtship ritual, (can vary slightly among species) the male again sings and rocks from side to side or pounds his abdomen on the substrate. If the female is receptive to his “romantic overtures,” she climbs onto his back, the male raises his tegmina at a 45° angle, and she begins feeding on a substance secreted from a glandular cavity, called the metanotal, metathoracic or Hancock’s gland (which he called the “alluring gland”) located between the wing bases. The secretions empty into a pit at the base of the male’s hind wings where they are accessible to the female once she is in the copulatory position. After she begins to feed, she allows the male to mate with her. During copulation, the male reaches his abdomen back, the female bends her abdomen downward connecting their genitalia, and the male passes a sperm-containing spermatophore to the female. The spermatophore is ovoid and possesses a thin, threadlike tube which enters the female, leaving the spermatophore to dangle outside her genital opening and, when internally attached, sperm begins to move through the tube. After copulation, the female always eats the spermatophore because it is thought to contain nutrients which may enhance egg production. The female remains astride the male for 5-20 minutes or more, continuing to feed from the metanotal gland. When she stops feeding, she dismounts, but the male may attempt to resume active courtship by repeatedly backing under the female until she either remounts or moves away. If remounting occurs, the renewed courtship may require another 20 minutes or more. Such resumed courtship and mating is thought to ensure that large numbers of sperm pass from his spermatophore into the female’s sperm-storage organ called the spermatheca. When the female is ready to lay eggs, sperm are released from the spermatheca and fertilize the eggs as they pass down the oviduct. The female selects a suitable egg-laying site on a woody or herbaceous plant to oviposit and chews a small hole in the stem, then moves forward slightly, arches her back, bringing her ovipositor perpendicular to the hole moving it up and down drilling the hole with thrusts and turning it around by twisting her abdomen. The drilling time may require 5-25 minutes, depending upon the plant’s wood or fiber density. Once the hole is drilled to the proper size and depth, the female moves an egg down her ovipositor, fills the hole with a mucilaginous substance, removes the ovipositor, and neatly caps the hole with chewed plant material. The entire process from chewing the bark to sealing the hole may take a quarter hour to nearly a full hour.

The Four-spotted Tree Cricket produces one generation per year. This species has been found to be especially fond of ovipositing its eggs in

Queen Anne’s Lace/Wild Carrot (

Daucus carota) when present, but also favors Goldenrod (

Solidago sp.) and other species in the

Asteracaeae family. Sometimes this species will select woody species in the genera

Rosa and

Rubus for egg laying. The female selects stems from 2-5 mm in diameter and drills into the pith. Sometimes the egg completely fills the hole. The puncture hole rows on the plant do not exhibit the compactness and regularity found in other

Oecanthus species. The rows are crooked and broken up into isolated punctures of 2-5 short rows, each grouping separated by 3-15 mm gaps. The holes are placed about one per millimeter and seldom are there more than 8 or 10 punctures in one group. After the female lays the egg, she chews off a small patch of outer plant tissue and pushes it into the hole and presses the frayed edges into a neatly, cryptic cap. When the eggs hatch, the nymphs pass through 5 instars before reaching the adult stage (Fulton 1915).

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Capinera, J.L. and T.S. Sechrist. 1982. Grasshoppers of Colorado: Identification, Biology, and Management. Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University Experiment Station, Bulletin 584S. 161 p.

Capinera, J.L. and T.S. Sechrist. 1982. Grasshoppers of Colorado: Identification, Biology, and Management. Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University Experiment Station, Bulletin 584S. 161 p. Capinera, J.L., R.D. Scott, and T.J. Walker. 2004. Field Guide to Grasshoppers, Katydids, and Crickets of the United States. Ithaca, NY. Cornell University Press.

Capinera, J.L., R.D. Scott, and T.J. Walker. 2004. Field Guide to Grasshoppers, Katydids, and Crickets of the United States. Ithaca, NY. Cornell University Press. Elliott, L. and W. Hershberger. 2007. The songs of insects. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 227 p.

Elliott, L. and W. Hershberger. 2007. The songs of insects. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 227 p. Fulton, B.B. 1915. The tree crickets of New York: life history and bionomics. New York Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 42.

Fulton, B.B. 1915. The tree crickets of New York: life history and bionomics. New York Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 42. Fulton, B.B. June 1926. The tree crickets of Oregon. Oregon Agricultural College Experiment Station, Station Bulletin 223. 20 p.

Fulton, B.B. June 1926. The tree crickets of Oregon. Oregon Agricultural College Experiment Station, Station Bulletin 223. 20 p. Fulton, B.B. October 1926. Geographical variation in the Nigrocornis group of Oecanthus (Orthoptera). Iowa State College Journal of Science 1(1):42-46.

Fulton, B.B. October 1926. Geographical variation in the Nigrocornis group of Oecanthus (Orthoptera). Iowa State College Journal of Science 1(1):42-46. Funk, D.H. 1982. The mating of tree crickets. Scientific American 261(2):50-59.

Funk, D.H. 1982. The mating of tree crickets. Scientific American 261(2):50-59. Hebard, M. 1928. The Orthoptera of Montana. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Vol. 80:211-306.

Hebard, M. 1928. The Orthoptera of Montana. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Vol. 80:211-306. Helfer, J.R. 1971. How to Know the Grasshoppers, Crickets, Cockroaches, and Their Allies. Revised edition (out of print), Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

Helfer, J.R. 1971. How to Know the Grasshoppers, Crickets, Cockroaches, and Their Allies. Revised edition (out of print), Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. Himmelman, J. 2009. Guide to Night-Singing Insects of the Northeast. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. 160 p.

Himmelman, J. 2009. Guide to Night-Singing Insects of the Northeast. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. 160 p. Scott, R.D. 2010. Montana Grasshoppers, Katydids, and Crickets A Pictorial Field Guide to the Orthoptera. MagpieMTGraphics, Billings, MT.

Scott, R.D. 2010. Montana Grasshoppers, Katydids, and Crickets A Pictorial Field Guide to the Orthoptera. MagpieMTGraphics, Billings, MT. Vickery, V. R. and D. K. M. Kevan. 1985. The grasshopper, crickets, and related insects of Canada and adjacent regions. Biosystematics Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario. Publication Number 1777. 918 pp.

Vickery, V. R. and D. K. M. Kevan. 1985. The grasshopper, crickets, and related insects of Canada and adjacent regions. Biosystematics Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario. Publication Number 1777. 918 pp. Walker T.J.(ed.). 2020. Singing insects of North America. Accessed 10 February 2021. https://orthsoc.org/sina/

Walker T.J.(ed.). 2020. Singing insects of North America. Accessed 10 February 2021. https://orthsoc.org/sina/ Walker, T.J. 1962. Factors responsible for intraspecific variation in the calling songs of crickets. Evolution 16:407-428.

Walker, T.J. 1962. Factors responsible for intraspecific variation in the calling songs of crickets. Evolution 16:407-428. Walker, T.J. 1963. The taxonomy and calling songs of United States tree crickets (Orthopters:Gryllidae:Oecanthus). The nigricornis group of the genus Oecanthus. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 56(6):772-789.

Walker, T.J. 1963. The taxonomy and calling songs of United States tree crickets (Orthopters:Gryllidae:Oecanthus). The nigricornis group of the genus Oecanthus. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 56(6):772-789.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Alexander, R.D. and D. Otte. 1967. The evolution of genitalia and mating behavior in crickets (Gryllidae) and other Orthoptera. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan. Misc. publications, Museum of Zoology, No. 133. 69 p.

Alexander, R.D. and D. Otte. 1967. The evolution of genitalia and mating behavior in crickets (Gryllidae) and other Orthoptera. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan. Misc. publications, Museum of Zoology, No. 133. 69 p. Bland, R.G. 2003. The Orthoptera of Michigan—Biology, Keys, and Descriptions of Grasshoppers, Katydids, and Crickets. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Extension, Bulletin E-2815. 221 p.

Bland, R.G. 2003. The Orthoptera of Michigan—Biology, Keys, and Descriptions of Grasshoppers, Katydids, and Crickets. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Extension, Bulletin E-2815. 221 p. Brown, W.D. 1997. Courtship feeding in tree crickets increases insemination and reproductive life span. Animal Behavior 54:1369-1382.

Brown, W.D. 1997. Courtship feeding in tree crickets increases insemination and reproductive life span. Animal Behavior 54:1369-1382. Dethier, V.G. 1992. Crickets and Katydids, Concerts and Solos. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 140 p.

Dethier, V.G. 1992. Crickets and Katydids, Concerts and Solos. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 140 p. Gangwere, S.K., M.C. Muralirangan, and M. Muralirangan (eds). 1997. The bionomics of grasshoppers, katydids and their kin. New York, NY: CAB International. 528 p.

Gangwere, S.K., M.C. Muralirangan, and M. Muralirangan (eds). 1997. The bionomics of grasshoppers, katydids and their kin. New York, NY: CAB International. 528 p. Himmelman, J. 2011. Cricket radio: tuning in the night-singing insects. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 272 p.

Himmelman, J. 2011. Cricket radio: tuning in the night-singing insects. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 272 p. Sater, S. 2022. The insects of Sevenmile Creek, a pictorial guide to their diversity and ecology. Undergraduate Thesis. Helena, MT: Carroll College. 242 p.

Sater, S. 2022. The insects of Sevenmile Creek, a pictorial guide to their diversity and ecology. Undergraduate Thesis. Helena, MT: Carroll College. 242 p. Walker, T.J. 1967. The metanotal gland as a taxonomic character in Oecanthus of the United States. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 69(2):151-167.

Walker, T.J. 1967. The metanotal gland as a taxonomic character in Oecanthus of the United States. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 69(2):151-167. Walker, T.J. 1969. Acoustic synchrony: two mechanisms in the snowy tree cricket. Science 166:891-894.

Walker, T.J. 1969. Acoustic synchrony: two mechanisms in the snowy tree cricket. Science 166:891-894.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Four-spotted Tree Cricket"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Insects"