View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Northern Alligator Lizard - Elgaria coerulea

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is uncommon across much of western Montana in suitable habitat. Little is known about population status and no trend information is available. Threats are not well studied but likely include forest fire, incidental and targeted collection, and predation by domestic cats.

General Description

EGGS:

This species is viviparous and does not lay eggs. Eggs develop internally and females give birth to live young. Broods include 2-15 young (typically 3-6), averaging about four (Lewis 1946, Pimentel 1959, Vitt 1973, Nussbaum et al. 1983, St. John 2002, Stebbins 2003).

HATCHLINGS:

Newly born young are about 2.0-3.0 cm (0.8-1.2 in) snout-vent length (SVL) and 7.5 cm (3 in) total length (TL) (Pimentel 1959, Vitt 1973, Nussbaum et al. 1983, Werner et al. 2004).

JUVENILES AND ADULTS:

The body is elongated, and the legs are short. The back is brown, tan, or gray to olive, yellow, or greenish. Juveniles have a broad reddish-tan stripe running the length of the back. The dark sides of the body are often checkered with small dark patches, and there is a distinctive dark patch around the eye (Stebbins 2003). The belly scale rows are edged with a darker area, giving the white to pale gray belly a banded appearance. There is a distinctive fold of skin running along each side of the body, extending between the legs, and revealing small granular scales when spread apart. Males have larger and broader triangular-shaped heads than do females. Adults are 7.0-10.0 cm (2.8-3.9 in) SVL and up to 20.0 cm (7.9 in) TL. No size dimorphism between the sexes, although sometimes within populations, females may be larger (Stewart 1985).

Diagnostic Characteristics

Body morphology (elongate body with short legs) and presence of a longitudinal fold of skin on each side of the body separates the Northern Alligator Lizard (

Elgaria coerulea) from other native lizard species to Montana. Western Skink (

Plestiodon skiltonianus) have a shiny appearance, distinct longitudinal stripes of brown, black, and golden-yellow, and a blue tail in juveniles and young adults. Greater Short-horned Lizard (

Phrynosoma hernandesi) are flattened, widened through the body, and “prickly” in appearance. The pale bellies of Common Sagebrush Lizard (

Sceloporus graciosus) and Western Fence Lizard (

S. occidentalis) lack darkened edging that gives the belly a banded appearance, they sometimes have blue patches on the belly and throat. Both species feel rough when handled, due to the keeled scales (St. John 2002, Stebbins 2003). Only the Western Skink is broadly sympatric with the Northern Alligator Lizard in western Montana. The Western Fence Lizard is present at one locality (Sanders County) within the range of

E. coerulea in Montana (Werner et al. 2004).

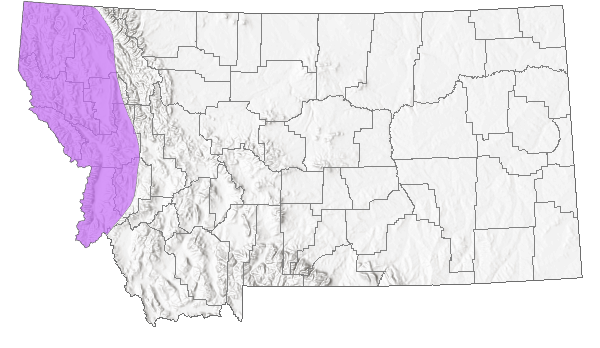

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Western Hemisphere Range

Range Comments

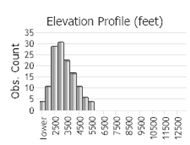

The Northern Alligator Lizard is one of seven species currently recognized in the genus Elgaria (Good 1988a, b); it was formerly included in the genus Gerrhonotus (Lais 1976). Four intergrading subspecies of Northern Alligator Lizard (E. coerulea coerulea, E. c. palmeri, E. c. principis, and E. c. shastensis) are recognized, with the Northwestern Alligator Lizard (E. c. pincipis) the form present in Montana (Fitch 1938, Lais 1976, Werner et al. 2004). The Northern Alligator Lizard is found at elevations from sea level to 3,200 m (10,500 ft), west of the Continental Divide, from southern British Columbia, south into northern Idaho and western Montana, and through northern and western Washington, western Oregon, the Coast Ranges and Sierra Nevada in California. Disjunct populations are present in southeast Oregon, northeast California, and northwestern Nevada along the state border (Lais 1976, Nussbaum et al. 1983, Vindum and Arnold 1997, St. John 2002, Stebbins 2003). The species also occurs on some coastal islands off Washington and California. In Montana, there are about 174 records from eight counties west of the Continental Divide, including a specimen from Wild Horse Island in Flathead Lake (Maxell et al. 2003, Werner et al. 2004, MTNHP POD 2023).

Maximum elevation: 1,774.2 m (5,821 ft) in Ravalli County (Matt Cashell, MTNHP POD 2023. 2003).

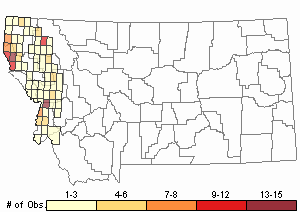

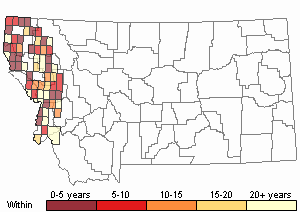

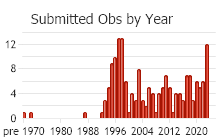

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 226

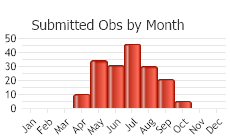

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

No information is currently available.

Habitat

The Northern Alligator Lizard occurs in areas cooler and more humid than tolerated by most lizards, but it does require some sunny clearings. It is found in coastal stand communities of stabilized dunes, mixed coniferous forest, often in grassy grown-over areas at margins of woodlands and in clear cuts. They can also use areas near streams with riparian strips of Aspen (

Populus tremuloides) or other tree and shrub species that can be dense, and in juniper-sagebrush and rabbitbrush habitats (Svihla 1942, Lais 1976, Stewart 1979, Nussbaum et al. 1983, Vindum and Arnold 1997, St. John 2002, Stebbins 2003). In these habitats it occurs on the ground often under downed wood and rocks, and in leaf and needle litter.

Habitat use in Montana has not been the subject of study, but records associated with encounters provide a sense of habitat requirements. Several observations of Northern Alligator Lizard have been made on south-facing slopes, in or at the margins of fine to coarse talus. Sometimes these sites have had little canopy cover, but more often there has been some cover of Douglas-fir (

Pseudotsuga menziesii) and Ponderosa Pine (

Pinus ponderosa). The understory contains a variety of shrubby species including Serviceberry (

Amelanchier sp.), Ninebark (

Physocarpus sp.), and Mock Orange (

Philadelphus sp.) with a litter layer of dried leaves and conifer needles, and can be fairly close to streams (Place 1989, Werner and Reichel 1994, Hendricks and Reichel 1996a, Werner et al. 1998, Boundy 2001, Paul Hendricks, personal observation).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Forest and Woodland

Low Elevation - Xeric Forest and Woodland

Montane - Subalpine Forest and Woodland

Shrubland

Foothills - Montane Shrubland

Grassland

Lowland - Prairie Grassland

Sparse and Barren

Sparse and Barren

Wetland and Riparian

Riparian and Wetland Forest

Recently Disturbed or Modified

Harvested Forest

Recently Burned

Human Land Use

Developed

Food Habits

Adults and juveniles actively forage, albeit not widely and sometimes haltingly in a slow stalk or propelled snake-like movement with the legs folded at the sides (Nussbaum et al. 1983, Place 1989, St. John 2002). Hunting is mainly by sight, but some evidence suggests they can identify prey by odor (Cooper 1990) resulting in one reason for high rates of tongue-flicking. Arthropods form most of the diet, but slugs and earthworms are also taken. Other prey types include snails, spiders, millipedes, centipedes, and ticks. Individuals in captivity have eaten neonatal mice (Cooper 1990, St. John 2002, Stebbins 2003). There is no information on the food habits of this species in Montana.

Ecology

Limited information is available for Montana. The Northern Alligator Lizard is a secretive species, most often found under logs and rocks. It is also frequently detected rustling through litter of dried leaves and needles or sunning in an exposed location. On the Washington coast, the body temperature ranged from 20 to 30 °C (68 to 86 °F) and correlated with substrate temperature. Males basked during the height of spermatogenesis. Basking may be especially important in high elevation populations.

The life history for this species has not been thoroughly studied. After emerging from winter hibernation, Northern Alligator Lizards are active during the day from April to September (Nussbaum et al. 1983, St. John 2002, Stebbins 2003). Animals have been found surface active in Montana from early April through September (Rodgers and Jellison 1942, Werner and Reichel 1994, Hendricks and Reichel 1996a, Boundy 2001); however, the hibernacula in Montana are not described.

Home range size has not been reported, but adults in coastal Washington are gregarious in early spring and fall, concentrating in localized hibernation sites (Vitt 1973). At a coastal California location most animals were relatively sedentary, usually being recaptured within 10 m (32.8 ft) of initial capture site. Marked lizards were never found outside the 1.5 ha study plot (Stewart 1985).

There is little information on the predators of this species. They readily drop their tails, and tails have been found in stomachs of snakes (Nussbaum et al. 1983). There are no reports of predation on this species in Montana.

Reproductive Characteristics

Studies from other locations of Northern Alligator Lizards have documented mating in April and May in coastal Washington (Svihla 1942, Lewis 1946, Vitt 1973), and elsewhere in the Pacific Northwest (Nussbaum et al. 1983). Gestation is about three months, with a single brood of live young born in August-September in coastal California and Washington (Lewis 1946, Vitt 1973, Stewart 1985). Females reach sexual maturity between 32 to 44 months in northern California (Nussbaum et al. 1983, Stewart 1985, St. Johns 2002, Stebbins 2003) with larger females producing larger clutches and young (Pimentel 1959, Stewart 1979). No information is available from Montana on any aspect of the reproductive biology of this species.

Additionally, no information is available on the longevity of Northern Alligator Lizard, but late age of maturity and low fecundity suggest long life expectancy (Vitt 1973, Stewart 1985). Annual mortality in a coastal California population was 46% for all juvenile size classes and 27% for adults (Stewart 1985). Adult female survivorship exceeding that of adult males.

Management

The following was taken from the Status and Conservation section for the Northern Alligator Lizard account in

Maxell et al. 2009.

At the time the comprehensive summaries of amphibians and reptiles in Montana (Maxell et al. 2003, Werner et al. 2004) were published, there were 74 total records for Northern Alligator Lizard from six counties west of the Continental Divide, with records concentrated near the Idaho state line, and extending east to the western base of the Whitefish Range and west slope of the Mission Mountains. With so few records, the current status in Montana is largely uncertain. The Northern Alligator Lizard has not been documented in Glacier National Park (Marnell 1997) but has been reported south of there in the Mission Mountains on the east side of the Flathead Valley (Brunson and Demaree 1951, Werner et al. 1998a). There is also a noticeable absence of records between the lower Clark Fork River and the Flathead Valley, despite seemingly suitable habitat in that region. The eastern extent of the range in Montana is poorly defined. Because the Northern Alligator Lizard has not been the focus of life history or population studies in Montana, it is difficult to identify conservation needs. On the local scale, limited data from California and Washington indicate this species is relatively sedentary and gregarious (Vitt 1973, Stewart 1985). Thus, populations appear vulnerable to habitat fragmentation, especially where valley bottom habitat is developed or dramatically altered. Population density measurements are not available for Montana and are few overall; a two-year mark-recapture study at a coastal California site resulted in a mean monthly estimate of 142-167 lizards for the 1.5 ha study area, and an average density of 95-111 lizards when adjusted for juvenile mortality (Stewart 1985). In British Columbia, they may be locally abundant, but are usually distributed sparsely (Gregory and Campbell 1984). To summarize, risk factors relevant to the viability of populations of this species are likely to include habitat loss/fragmentation, fire, road and trail development, quarrying, river/stream impoundment, and use of pesticides and herbicides. However, perhaps the greatest risk to maintaining viable populations of Northern Alligator Lizard in Montana is the lack of baseline data on its distribution, status, habitat use, and basic biology (Maxell and Hokit 1999). These data are needed to monitor trends and recognize dramatic declines when and where they occur. No studies address or identify risk factors. The presence of Northern Alligator Lizard in “cut-over areas” indicates some degree of tolerance to canopy removal, so long as ground cover remains (Nussbaum et al. 1983). Some vegetative cover or talus appears to be desirable in areas where foraging occurs. Invasion of exotic weeds into occupied habitat has and continues to occur in western Montana, but it is unclear how associated habitat changes may affect populations. Use of chemical agents to control weed and insect pest infestations could depress populations of Northern Alligator Lizard, which feed on ground-dwelling arthropods. Several Northern Alligator Lizards died in the laboratory after they ate caterpillars of the cinnabar moth, an introduced pest control agent for controlling poisonous Tansy Ragweed (

Senecio jacobaea), and there is a possibility that this exotic moth may have adverse effects on Northern Alligator Lizard populations (Nussbaum et al. 1983).

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Boundy, J. 2001. Herpetofaunal surveys in the Clark Fork Valley region, Montana. Herpetological Natural History 8: 15-26.

Boundy, J. 2001. Herpetofaunal surveys in the Clark Fork Valley region, Montana. Herpetological Natural History 8: 15-26. Brunson, R.B. and H.A. Demaree, Jr. 1951. The herpetology of the Mission Mountains, Montana. Copeia (4):306-308.

Brunson, R.B. and H.A. Demaree, Jr. 1951. The herpetology of the Mission Mountains, Montana. Copeia (4):306-308. Cooper, W.E. 1990b. Prey odor discrimination by anguid lizards. Herpetologica 46(2): 183-190.

Cooper, W.E. 1990b. Prey odor discrimination by anguid lizards. Herpetologica 46(2): 183-190. Fitch, H.S. 1938. A systematic account of the alligator lizards (Gerrhonotus) in the western United States and lower California. American Midland Naturalist 20: 381-424.

Fitch, H.S. 1938. A systematic account of the alligator lizards (Gerrhonotus) in the western United States and lower California. American Midland Naturalist 20: 381-424. Good, D.A. 1988a. Allozyme variation and phylogenetic relationships among the species of Elgaria (Squamata: Anguidae). Herpetologica 44: 154-162.

Good, D.A. 1988a. Allozyme variation and phylogenetic relationships among the species of Elgaria (Squamata: Anguidae). Herpetologica 44: 154-162. Good, D.A. 1988b. Phylogenetic relationships among gerrhonotine lizards: an analysis of external morphology. University of California Publications in Zoology 121: 1-139.

Good, D.A. 1988b. Phylogenetic relationships among gerrhonotine lizards: an analysis of external morphology. University of California Publications in Zoology 121: 1-139. Gregory, P. T. and R. W. Campbell. 1984. The reptiles of British Columbia. British Columbia Provincial Museum, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. 102 pp.

Gregory, P. T. and R. W. Campbell. 1984. The reptiles of British Columbia. British Columbia Provincial Museum, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. 102 pp. Hendricks, P. and J.D. Reichel. 1996a. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Bitterroot National Forest: 1995. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 95 p.

Hendricks, P. and J.D. Reichel. 1996a. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Bitterroot National Forest: 1995. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 95 p. Lais, P. M. 1976. Gerrhonotus coeruleus. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 178.1-178.4.

Lais, P. M. 1976. Gerrhonotus coeruleus. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 178.1-178.4. Marnell, L.F. 1996. Amphibian survey of Glacier National Park, Montana. Abstract. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 2(2): 52.

Marnell, L.F. 1996. Amphibian survey of Glacier National Park, Montana. Abstract. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 2(2): 52. Maxell, B.A. and D.G. Hokit. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles. Pages 2.1– 2.30 In G. Joslin and H. Youmans, committee chairs. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a compendium of the current state of understanding in Montana. Committee on Effects of Recreation on Wildlife, Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Maxell, B.A. and D.G. Hokit. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles. Pages 2.1– 2.30 In G. Joslin and H. Youmans, committee chairs. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a compendium of the current state of understanding in Montana. Committee on Effects of Recreation on Wildlife, Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. Maxell, B.A., J.K. Werner, P. Hendricks, and D.L. Flath. 2003. Herpetology in Montana: a history, status summary, checklists, dichotomous keys, accounts for native, potentially native, and exotic species, and indexed bibliography. Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology, Northwest Fauna Number 5. Olympia, WA. 135 p.

Maxell, B.A., J.K. Werner, P. Hendricks, and D.L. Flath. 2003. Herpetology in Montana: a history, status summary, checklists, dichotomous keys, accounts for native, potentially native, and exotic species, and indexed bibliography. Society for Northwestern Vertebrate Biology, Northwest Fauna Number 5. Olympia, WA. 135 p. Maxell, B.A., P. Hendricks, M.T. Gates, and S. Lenard. 2009. Montana amphibian and reptile status assessment, literature review, and conservation plan, June 2009. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 643 p.

Maxell, B.A., P. Hendricks, M.T. Gates, and S. Lenard. 2009. Montana amphibian and reptile status assessment, literature review, and conservation plan, June 2009. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 643 p. Nussbaum, R.A., E.D. Brodie, Jr. and R.M. Storm. 1983. Amphibians and reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. University of Idaho Press. Moscow, ID. 332 pp.

Nussbaum, R.A., E.D. Brodie, Jr. and R.M. Storm. 1983. Amphibians and reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. University of Idaho Press. Moscow, ID. 332 pp. Place, C.B., III. 1989. Mountain Gator. Montana Outdoors 20(4): 27-29.

Place, C.B., III. 1989. Mountain Gator. Montana Outdoors 20(4): 27-29. Rodgers, T. L. and W. L. Jellison. 1942. A collection of amphibians and reptiles from western Montana. Copeia (1):10-13.

Rodgers, T. L. and W. L. Jellison. 1942. A collection of amphibians and reptiles from western Montana. Copeia (1):10-13. St. John, A.D. 2002. Reptiles of the northwest: California to Alaska, Rockies to the coast. Lone Pine Publishing, Renton, WA. 272 p.

St. John, A.D. 2002. Reptiles of the northwest: California to Alaska, Rockies to the coast. Lone Pine Publishing, Renton, WA. 272 p. Stebbins, R. C. 2003. A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York. 533 p.

Stebbins, R. C. 2003. A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York. 533 p. Stewart, J. R. 1979. The Balance Between Number and Size of Young in the Live Bearing Lizard Gerrhomotus Coerulens. Herpetologica 35:342-350.

Stewart, J. R. 1979. The Balance Between Number and Size of Young in the Live Bearing Lizard Gerrhomotus Coerulens. Herpetologica 35:342-350. Stewart, J.R. 1985. Growth and survivorship in a California population of Gerrhonotus coerulens, with comments on intraspecific variation in adult female size. American Midland Naturalist 113: 30-44.

Stewart, J.R. 1985. Growth and survivorship in a California population of Gerrhonotus coerulens, with comments on intraspecific variation in adult female size. American Midland Naturalist 113: 30-44. Svihla, A. 1942. Mating behavior of the northern alligator lizard. Copeia 1942(1): 52.

Svihla, A. 1942. Mating behavior of the northern alligator lizard. Copeia 1942(1): 52. Vindum, J.V. and E.N. Arnold. 1997. The northern alligator lizard (Elgaria coerulea) from Nevada. Herpetological Review 28: 100.

Vindum, J.V. and E.N. Arnold. 1997. The northern alligator lizard (Elgaria coerulea) from Nevada. Herpetological Review 28: 100. Vitt, L. J. 1973. Reproductive Biology of the Anguid Lizard, Gerrhonotus Coerulens Principis. Herpetologica 29:176-184.

Vitt, L. J. 1973. Reproductive Biology of the Anguid Lizard, Gerrhonotus Coerulens Principis. Herpetologica 29:176-184. Werner, J.K. and J.D. Reichel. 1994. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Kootenai National Forest: 1994. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 104 p.

Werner, J.K. and J.D. Reichel. 1994. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Kootenai National Forest: 1994. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 104 p. Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks and D.L. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and Reptiles of Montana. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, MT. 262 pp.

Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks and D.L. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and Reptiles of Montana. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, MT. 262 pp. Werner, J.K., T. Plummer, and J. Weaslehead. 1998a. Amphibians and reptiles of the Flathead Indian Reservation. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 4(1-2): 33-49.

Werner, J.K., T. Plummer, and J. Weaslehead. 1998a. Amphibians and reptiles of the Flathead Indian Reservation. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 4(1-2): 33-49.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Avise, J.C., B.W. Bowen, T. Lamb, A.B. Meylan, and E. Birmingham. 1992. Mitochondrial DNA evolution at a turtle's pace: evidence for low genetic variability and reduced microevolutionary rate in the Testudines. Molecular Biological Evolution 9:457-473.

Avise, J.C., B.W. Bowen, T. Lamb, A.B. Meylan, and E. Birmingham. 1992. Mitochondrial DNA evolution at a turtle's pace: evidence for low genetic variability and reduced microevolutionary rate in the Testudines. Molecular Biological Evolution 9:457-473. Banta, B.H., C.R. Mahrdt, and K.R. Beaman. 1996. Reptilia: Squamata: Sauria: Anguidae: Elgaria panamintina. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 629.1-629.4

Banta, B.H., C.R. Mahrdt, and K.R. Beaman. 1996. Reptilia: Squamata: Sauria: Anguidae: Elgaria panamintina. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 629.1-629.4 Boundy, J. and T.G. Balgooyen. 1988. Record lengths for some amphibians and reptiles from the western United States. Herpetological Review 19(2): 26-27.

Boundy, J. and T.G. Balgooyen. 1988. Record lengths for some amphibians and reptiles from the western United States. Herpetological Review 19(2): 26-27. Bowker, R.W. 1987. Elgaria kingi (arizona alligator lizard). Aantipredator behavior. Herpetological Review 18(4): 73, 75.

Bowker, R.W. 1987. Elgaria kingi (arizona alligator lizard). Aantipredator behavior. Herpetological Review 18(4): 73, 75. Bowker, R.W. 1988a. A comparative behavioral study and taxonomic analysis of Gerrhonotine lizards. Ph.D. Dissertation, Arizona StateUniversity 139p. 1988.

Bowker, R.W. 1988a. A comparative behavioral study and taxonomic analysis of Gerrhonotine lizards. Ph.D. Dissertation, Arizona StateUniversity 139p. 1988. Bowker, R.W. 1988b. Comparative courtship behavior of Gerrhonotine lizards. Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science 23(Suppl.): 13.

Bowker, R.W. 1988b. Comparative courtship behavior of Gerrhonotine lizards. Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science 23(Suppl.): 13. Bowker, R.W. 1994a. Elgaria kingi (arizona alligator lizard). Size. Herpetological Review 25(3): 121.

Bowker, R.W. 1994a. Elgaria kingi (arizona alligator lizard). Size. Herpetological Review 25(3): 121. Brunson, R.B. 1955. Check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 15: 27-29.

Brunson, R.B. 1955. Check list of the amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 15: 27-29. Cooper, W.E., Jr. 1995. Strike-induced chemosensory searching by the anguid lizard Elgaria coerulea. Amphibia-Reptilia 16(2):147-156.

Cooper, W.E., Jr. 1995. Strike-induced chemosensory searching by the anguid lizard Elgaria coerulea. Amphibia-Reptilia 16(2):147-156. Cope, E.D. 1875. Check-list of North American Batrachia and Reptilia; with a systematic list of the higher groups, and an essay on geographical distribution. Based on the specimens contained in the U.S. National Museum. U.S. Natioanl Museum Bulletin 1: 1-104.

Cope, E.D. 1875. Check-list of North American Batrachia and Reptilia; with a systematic list of the higher groups, and an essay on geographical distribution. Based on the specimens contained in the U.S. National Museum. U.S. Natioanl Museum Bulletin 1: 1-104. Criley, B.B. 1986. The cranial ostelogy of gerrhonotiform lizards. American Midland Naturalist 80:199-219.

Criley, B.B. 1986. The cranial ostelogy of gerrhonotiform lizards. American Midland Naturalist 80:199-219. Crother, B.I. (ed.) 2008. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico. SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 37:1-84.

Crother, B.I. (ed.) 2008. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico. SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 37:1-84. Farmer, P. and S.B. Heath. 1987. Wildlife baseline inventory, Rock Creek study area, Sanders County, Montana. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT.

Farmer, P. and S.B. Heath. 1987. Wildlife baseline inventory, Rock Creek study area, Sanders County, Montana. Western Technology and Engineering, Inc. Helena, MT. Fitch, H.S. 1934a. A shift of specific names in the genus Gerrhonotus. Copeia 1934: 172-173.

Fitch, H.S. 1934a. A shift of specific names in the genus Gerrhonotus. Copeia 1934: 172-173. Fitch, H.S. 1934b. New alligator lizards from the Pacific Coast. Copeia 1934: 6-7.

Fitch, H.S. 1934b. New alligator lizards from the Pacific Coast. Copeia 1934: 6-7. Fitch, H.S. 1935. Natural history of the alligator lizards. Transactions of the Academy of Sciences in St. Louis 29: 1-38, 4 pls.

Fitch, H.S. 1935. Natural history of the alligator lizards. Transactions of the Academy of Sciences in St. Louis 29: 1-38, 4 pls. Franz, R. 1971. Notes on the distribution and ecology of the herpetofauna of northwestern Montana. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 7: 1-10.

Franz, R. 1971. Notes on the distribution and ecology of the herpetofauna of northwestern Montana. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 7: 1-10. Freeman, D.M., D.K. Hendrix, D. Shah, L.F. Fan, and T.F. Weiss. 1993. Effect of lymph composition on an in vitro preparation of the alligator lizard cochlea. Hearing Research 65(1-2): 83-98.

Freeman, D.M., D.K. Hendrix, D. Shah, L.F. Fan, and T.F. Weiss. 1993. Effect of lymph composition on an in vitro preparation of the alligator lizard cochlea. Hearing Research 65(1-2): 83-98. Goldberg, S.R. and C.R. Bursey. 1991c. Gastrointestinal helminths of the northwestern alligator lizard, Gerrhonotus coeruleus principis (Anguidae). Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 58(2): 246-248.

Goldberg, S.R. and C.R. Bursey. 1991c. Gastrointestinal helminths of the northwestern alligator lizard, Gerrhonotus coeruleus principis (Anguidae). Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 58(2): 246-248. Good, D.A. 1985. Studies of interspecific and intraspecific variation in the alligator lizards (Lacertillia: Anguidae: Gerrhonotinae). Ph.D. Dissertation. University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA. 622 p.

Good, D.A. 1985. Studies of interspecific and intraspecific variation in the alligator lizards (Lacertillia: Anguidae: Gerrhonotinae). Ph.D. Dissertation. University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA. 622 p. Good, D.A. 1987b. An allozyme analysis of anguid subfamilial relationships (Lacertilia: anguidae). Copeia 1987(3): 696-701.

Good, D.A. 1987b. An allozyme analysis of anguid subfamilial relationships (Lacertilia: anguidae). Copeia 1987(3): 696-701. Good, D.A. Cranial ossification in the northern alligator lizard, Elgaria coerulea (Squamata, Anguidae). Amphibia-Reptilia 16(2): 157-166.

Good, D.A. Cranial ossification in the northern alligator lizard, Elgaria coerulea (Squamata, Anguidae). Amphibia-Reptilia 16(2): 157-166. Grismer, L.L. 1988. Geographic variation, taxonomy, and biogeography of the anguid genus Elgaria (reptilia: squamata) in Baja California, Mexico. Herpetologica 44(4): 431-439.

Grismer, L.L. 1988. Geographic variation, taxonomy, and biogeography of the anguid genus Elgaria (reptilia: squamata) in Baja California, Mexico. Herpetologica 44(4): 431-439. Hanauska-Brown, L., B.A. Maxell, A. Petersen, and S. Story. 2014. Diversity Monitoring in Montana 2008-2010 Final Report. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Helena, MT. 78 pp.

Hanauska-Brown, L., B.A. Maxell, A. Petersen, and S. Story. 2014. Diversity Monitoring in Montana 2008-2010 Final Report. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Helena, MT. 78 pp. Hendricks, P. 1997. Lee Metcalf National Wildlife Refuge preliminary amphibian and reptile investigations: 1996. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 21 p.

Hendricks, P. 1997. Lee Metcalf National Wildlife Refuge preliminary amphibian and reptile investigations: 1996. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 21 p. Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. Kingsbury, B.A. 1992. The thermal ecology of the southern alligator lizard, Elgaria multicarinata. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California (Riverside); 119p. 1991.

Kingsbury, B.A. 1992. The thermal ecology of the southern alligator lizard, Elgaria multicarinata. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California (Riverside); 119p. 1991. Kingsbury, B.A. 1993. Thermoregulatory set points of the eurythermic lizard Elgaria multicarinata. Journal of Herpetology 27(3): 241-247.

Kingsbury, B.A. 1993. Thermoregulatory set points of the eurythermic lizard Elgaria multicarinata. Journal of Herpetology 27(3): 241-247. Kingsbury, B.A. 1994b. Thermal constraints and eurythermy in the lizard Elgaria multicarinata. Herpetologica 50(3): 266-273.

Kingsbury, B.A. 1994b. Thermal constraints and eurythermy in the lizard Elgaria multicarinata. Herpetologica 50(3): 266-273. Kingsbury, B.A. 1995. Field metabolic rates of a eurythermic lizard. Herpetologica 51(2): 155-159.

Kingsbury, B.A. 1995. Field metabolic rates of a eurythermic lizard. Herpetologica 51(2): 155-159. Loeza-Corichi, A. and O. Flores-Villela. 1995. Elgaria kingii (madrean alligator lizard). Herpetologial Review 26(2): 108.

Loeza-Corichi, A. and O. Flores-Villela. 1995. Elgaria kingii (madrean alligator lizard). Herpetologial Review 26(2): 108. Macey, J. R., J. A. Schulte, II, A. Larson, B. S. Tuniyev, N. Orlov, and T. J. Papenfuss. 1999. Molecular phylogenetics, tRNA evolution, and historical biogeography in anguid lizards and related taxonomic families. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 12:250-272.

Macey, J. R., J. A. Schulte, II, A. Larson, B. S. Tuniyev, N. Orlov, and T. J. Papenfuss. 1999. Molecular phylogenetics, tRNA evolution, and historical biogeography in anguid lizards and related taxonomic families. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 12:250-272. Maxell, B.A. 2009. State-wide assessment of status, predicted distribution, and landscapelevel habitat suitability of amphibians and reptiles in Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Missoula, MT: Wildlife Biology Program, University of Montana. 294 p.

Maxell, B.A. 2009. State-wide assessment of status, predicted distribution, and landscapelevel habitat suitability of amphibians and reptiles in Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Missoula, MT: Wildlife Biology Program, University of Montana. 294 p. Northrop, Devine & Tarbell, Inc. 1994. Cabinet Gorge and Noxon Rapids hydroelectric developments: 1993 wildlife study. Unpublished report to the Washington Water Power Company, Spokane. Vancouver, Washington and Portland, Maine. 144 pp. plus appendices.

Northrop, Devine & Tarbell, Inc. 1994. Cabinet Gorge and Noxon Rapids hydroelectric developments: 1993 wildlife study. Unpublished report to the Washington Water Power Company, Spokane. Vancouver, Washington and Portland, Maine. 144 pp. plus appendices. Reichel, J. and D. Flath. 1995. Identification of Montana's amphibians and reptiles. Montana Outdoors 26(3):15-34.

Reichel, J. and D. Flath. 1995. Identification of Montana's amphibians and reptiles. Montana Outdoors 26(3):15-34. Rutherford, P.L. and P.T. Gregory. 2003a. Habitat use and movement patterns of northern alligator lizards (Elgaria coerulea) and western skinks (Eumeces skiltonianus) in southeastern British Columbia. Journal of Herpetology 37: 98-106.

Rutherford, P.L. and P.T. Gregory. 2003a. Habitat use and movement patterns of northern alligator lizards (Elgaria coerulea) and western skinks (Eumeces skiltonianus) in southeastern British Columbia. Journal of Herpetology 37: 98-106. Rutherford, P.L. and P.T. Gregory. 2003b. How age, sex, and reproductive condition affect retreat-site selection and emergence patterns in a temperate-zone lizard, Elgaria coerulea. Ecoscience 10(1):24-32.

Rutherford, P.L. and P.T. Gregory. 2003b. How age, sex, and reproductive condition affect retreat-site selection and emergence patterns in a temperate-zone lizard, Elgaria coerulea. Ecoscience 10(1):24-32. Smith, H.M. 1986. The generic allocation of two species of mexican anguid lizards. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 22(1): 21-22. 1986.

Smith, H.M. 1986. The generic allocation of two species of mexican anguid lizards. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 22(1): 21-22. 1986. Spengler, J.C. and H.M. Smith. 1983 Intact exuviae in lizards. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 19(1) :24-26.

Spengler, J.C. and H.M. Smith. 1983 Intact exuviae in lizards. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 19(1) :24-26. Stebbins, R.C. 1958. A new alligator lizard form the Panamnit Mountains, Inyo County, California. American Museum of Novitates 1883:1-27.

Stebbins, R.C. 1958. A new alligator lizard form the Panamnit Mountains, Inyo County, California. American Museum of Novitates 1883:1-27. Storm, R. M., and W. P. Leonard (eds.). 1995. Reptiles of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society. Seattle, WA. 176 pp.

Storm, R. M., and W. P. Leonard (eds.). 1995. Reptiles of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society. Seattle, WA. 176 pp. Thompson, Richard W., Western Resource Dev. Corp., Boulder, CO., 1996, Wildlife baseline report for the Montana [Montanore] Project, Lincoln and Sanders counties, Montana. In Application for a Hard Rock Operating Permit and Proposed Plan of Operation, Montanore Project, Lincoln and Sanders Counties, Montana. Vol. 5. Stroiazzo, John. Noranda Minerals Corp., Libby, MT. Revised September 1996.

Thompson, Richard W., Western Resource Dev. Corp., Boulder, CO., 1996, Wildlife baseline report for the Montana [Montanore] Project, Lincoln and Sanders counties, Montana. In Application for a Hard Rock Operating Permit and Proposed Plan of Operation, Montanore Project, Lincoln and Sanders Counties, Montana. Vol. 5. Stroiazzo, John. Noranda Minerals Corp., Libby, MT. Revised September 1996. Tihen, J.A. 1949. The genera of gerrhonotine lizards. American Midland Naturalist 41(3): 580-601.

Tihen, J.A. 1949. The genera of gerrhonotine lizards. American Midland Naturalist 41(3): 580-601. Timken, R. No Date. Amphibians and reptiles of the Beaverhead National Forest. Western Montana College, Dillon, MT. 16 p.

Timken, R. No Date. Amphibians and reptiles of the Beaverhead National Forest. Western Montana College, Dillon, MT. 16 p. Werner, J.K. and J.D. Reichel. 1996. Amphibian and reptile monitoring/survey of the Kootenai National Forest: 1995. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 115 pp.

Werner, J.K. and J.D. Reichel. 1996. Amphibian and reptile monitoring/survey of the Kootenai National Forest: 1995. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 115 pp. Werner, J.K. and T. Plummer. 1995a. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Flathead Indian Reservation 1993-1994. Salish Kootenai College, Pablo, MT. 55 pp.

Werner, J.K. and T. Plummer. 1995a. Amphibian and reptile survey of the Flathead Indian Reservation 1993-1994. Salish Kootenai College, Pablo, MT. 55 pp. Werner, J.K. and T. Plummer. 1995b. Amphibian monitoring program on the Flathead Indian Reservation 1995. Salish Kootenai College, Pablo, MT. 46 p.

Werner, J.K. and T. Plummer. 1995b. Amphibian monitoring program on the Flathead Indian Reservation 1995. Salish Kootenai College, Pablo, MT. 46 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Northern Alligator Lizard"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Reptiles"