View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Western Spotted Skunk - Spilogale gracilis

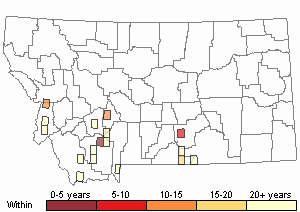

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is rare and difficult to detect. It has been observed 17 times in the state and only twice in the last decade. Range is uncertain, trends and threats are poorly characterized

General Description

The Western Spotted Skunk is a small, relatively slender skunk with glossy black fur interrupted with distinct white stripes on the forward part of the body. The posterior part of the body has two interrupted white bands with one white spot on each side of the rump and two more at the base of the tail. The pattern of white lines and spots is individually unique. The top of the tail is black and the underside is extensively white. The tip of the tail is white. A white spot is present on the forehead and another in front of each ear. External measurements in males average 411 millimeters in total length, 122 millimeters for the tail and 50 millimeters for the hind foot. In females, external measurements average 387 millimeters in total length, 116 millimeters for the tail, and 47 millimeters for the hind foot. Males weigh about 630 grams, whereas females weigh about 450 grams (Foresman 2012).

Diagnostic Characteristics

The distinctive black and white pattern of spots and stripes and much smaller size of the Western Spotted Skunk distinguish them from the more common Stripped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis), which have two solid white stripes along the side of the body and are nearly twice as large.

The color pattern resembles that of the Eastern Spotted Skunk, but the white markings are more extensive. The black and white stripes on the upper back are nearly equal in width whereas in the Eastern Spotted Skunk the black areas are much more extensive than the white. The tip of the tail is white while the tail tips of Eastern Spotted Skunks are black. In addition to external characteristics, the breeding cycle of the spotted skunks are different (see Reproduction below).

Only Western Spotted Skunks and Striped Skunks are known to occur in Montana, however Eastern Spotted Skunks may also occur in the southeastern part of the state (Foresman 2012).

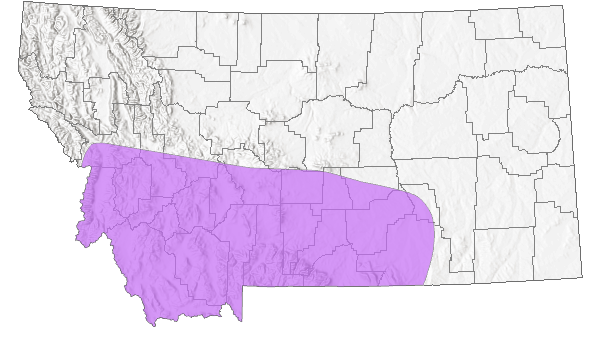

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Global Range

Estimated global breeding range area is: 3,910,242 km

2 (Approximately 3% in Montana)

See information about

iNaturalist Geomodels

iNaturalist Geomodels

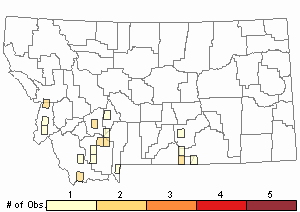

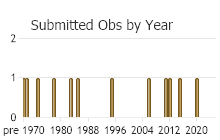

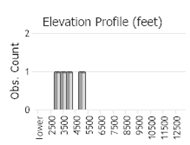

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 23

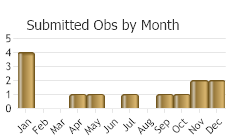

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

Western Spotted Skunks are non-migratory.

Habitat

The habitat of the Western Spotted Skunk in Montana is not well known, but they have been found in arid, rocky and brushy canyons and hillsides. Information from other portions of its range suggest that when they are inactive or bearing young they occupy a den in rocks, burrows, hollow logs, brush piles, or under buildings.

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Forest and Woodland

Deciduous Forest and Woodland

Low Elevation - Xeric Forest and Woodland

Montane - Subalpine Forest and Woodland

Shrubland

Arid - Saline Shrubland

Foothills - Montane Shrubland

Sagebrush Shrubland

Grassland

Lowland - Prairie Grassland

Sparse and Barren

Sparse and Barren

Wetland and Riparian

Alkaline - Saline Wetlands

Riparian and Wetland Forest

Riparian Shrubland

Human Land Use

Developed

Food Habits

Diets of Western Spotted Skunks in Montana have not been studied. Insects, rodents, small birds, and possibly bird eggs constitute most of their diet (Ingles 1965). Reptiles and amphibians are also taken (Leopold 1959), as are many types of fruits and berries.

Ecology

Ecological data is not available for this species in Montana. In general, den sites may be used by more than one individual, but adults are essentially solitary and nocturnal (Foresman 2012). Western Spotted Skunks may be locally common for a few years and then not seen for several more years (Pattie and Hoffmann 1992). Predators are not well known, but Great Horned Owls (Bubo virginianus) are probably the most important. Other sources of mortality include vehicles and deliberate killing by man, either by trapping or when they occur near human habitation. This species is probably best know for its habit of standing on its forelegs while arching its back and turning its hindquarters so that its anal glands are pointed at its antagonist when the animal feels threatened.

Reproductive Characteristics

No specific reproductive information for Montana is available, but information from other portions of its range suggests females come into estrus in September and most of them are bred by early October. Implantation of the embryo is delayed with the blastula stage of the embryo spending 180 to 200 days floating in the uterus of the female before becoming implanted. An average of four young are born in late April and May after a total gestation period of from 210 to 230 days. Young males may become sexually mature when only 3 or 4 months of age. Young leave the natal den about 1 month after birth and follow their mother until weaned at 7 weeks of age. Eastern Spotted Skunks do have delayed implantation. They mate between March and April and are reproductively isolated from the Western Spotted Skunk.

Management

Western Spotted Skunks are a Montana species of concern because of the limited number or records and limited distribution within the state. They are classified as a predator by Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks for regulatory purposes. Harvest is not regulated and Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks has recently requested information from trappers concerning take of this species to better define its range and status in Montana.

Stewardship Responsibility

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Foresman, K.R. 2012. Mammals of Montana. Second edition. Mountain Press Publishing, Missoula, Montana. 429 pp.

Foresman, K.R. 2012. Mammals of Montana. Second edition. Mountain Press Publishing, Missoula, Montana. 429 pp. Ingles, L.G. 1965. Mammals of the Pacific states. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California. 506 pp.

Ingles, L.G. 1965. Mammals of the Pacific states. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California. 506 pp. Leopold, A.S. 1959. Wildlife of Mexico. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Leopold, A.S. 1959. Wildlife of Mexico. University of California Press, Berkeley. Pattie, D.L. and R.S. Hoffmann. 1992. Mammals of the North American Parks and Prairies. Self published.

Pattie, D.L. and R.S. Hoffmann. 1992. Mammals of the North American Parks and Prairies. Self published.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Allen, A.W. 1987. The relationship between habitat and furbearers. Pages 164-179 in M. Novak, J.A. Baker, M.E. Obbard, and B. Malloch, eds. Wild Furbearer Management and Conservation in North America. Ontario Trappers Assn. and Ontario Ministry Nat. Res., Toronto, Ontario.

Allen, A.W. 1987. The relationship between habitat and furbearers. Pages 164-179 in M. Novak, J.A. Baker, M.E. Obbard, and B. Malloch, eds. Wild Furbearer Management and Conservation in North America. Ontario Trappers Assn. and Ontario Ministry Nat. Res., Toronto, Ontario. Chapman, J.A., and G.A. Feldhamer. 1982. Wild mammals of North America: biology, management, and economics. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Chapman, J.A., and G.A. Feldhamer. 1982. Wild mammals of North America: biology, management, and economics. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland. Deems, E.F., Jr. and D. Pursley (eds). 1978. North American furbearers: their management, research and harvest status in 1976. Int. Assoc. Fish and Wildlife Agencies and University of Maryland. 171 p.

Deems, E.F., Jr. and D. Pursley (eds). 1978. North American furbearers: their management, research and harvest status in 1976. Int. Assoc. Fish and Wildlife Agencies and University of Maryland. 171 p. Dragoo, J. W., and R. L. Honeycutt. 1997. Systematics of mustelid-like carnivores. Journal of Mammalogy 78:426-443.

Dragoo, J. W., and R. L. Honeycutt. 1997. Systematics of mustelid-like carnivores. Journal of Mammalogy 78:426-443. Flath, D.L. 1979. Nongame species of special interest or concern: Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes. Wildlife Division, Montana Department of Fish and Game. Helena, MT.

Flath, D.L. 1979. Nongame species of special interest or concern: Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes. Wildlife Division, Montana Department of Fish and Game. Helena, MT. Foresman, K.R. 2001. The wild mammals of Montana. American Society of Mammalogists, Special Publication Number 12. Lawrence, KS. 278 pp.

Foresman, K.R. 2001. The wild mammals of Montana. American Society of Mammalogists, Special Publication Number 12. Lawrence, KS. 278 pp. Hall, E.R. 1981. The mammals of North America, volumes I and II. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. 1181 pp.

Hall, E.R. 1981. The mammals of North America, volumes I and II. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. 1181 pp. Hoffmann, R.S. and D.L. Pattie. 1968. A guide to Montana mammals: identification, habitat, distribution, and abundance. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 133 p.

Hoffmann, R.S. and D.L. Pattie. 1968. A guide to Montana mammals: identification, habitat, distribution, and abundance. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 133 p. Hoffmann, R.S., P.L. Wright, and F.E. Newby. 1969. The distribution of some mammals in Montana. I. Mammals other than bats. Journal of Mammalogy 50(3): 579-604.

Hoffmann, R.S., P.L. Wright, and F.E. Newby. 1969. The distribution of some mammals in Montana. I. Mammals other than bats. Journal of Mammalogy 50(3): 579-604. Jellison, W.C. 1931. Little spotted skunk (Spilogale gracilis saxatilis), recorded for Montana. Journal of Mammalogy. V12. Page 314.

Jellison, W.C. 1931. Little spotted skunk (Spilogale gracilis saxatilis), recorded for Montana. Journal of Mammalogy. V12. Page 314. Jellison, W.L. 1945. General Notes: Spotted skunk and feral nutria in Montana. Journal of Mammalogy. 26(4): 432-443.

Jellison, W.L. 1945. General Notes: Spotted skunk and feral nutria in Montana. Journal of Mammalogy. 26(4): 432-443. Jones, J. K., Jr., R. S. Hoffman, D. W. Rice, C. Jones, R. J. Baker, and M. D. Engstrom. 1992. Revised checklist of North American mammals north of Mexico, 1991. Occasional Papers, The Museum, Texas Tech University, 146:1-23.

Jones, J. K., Jr., R. S. Hoffman, D. W. Rice, C. Jones, R. J. Baker, and M. D. Engstrom. 1992. Revised checklist of North American mammals north of Mexico, 1991. Occasional Papers, The Museum, Texas Tech University, 146:1-23. Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. McDonough, M.M., A.W. Ferguson, R.C. Dowler, M.E. Gompper, and J.E. Maldonado. 2020. In Press Phylogenomic systematics of the spotted skunks (Carnivora, Mephitidae, Spilogale): Additional species diversity and Pleistocene climate change as a major driver of diversification. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 167:107266

McDonough, M.M., A.W. Ferguson, R.C. Dowler, M.E. Gompper, and J.E. Maldonado. 2020. In Press Phylogenomic systematics of the spotted skunks (Carnivora, Mephitidae, Spilogale): Additional species diversity and Pleistocene climate change as a major driver of diversification. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 167:107266 Mead, R.A. 1968. Reproduction in western forms of the spotted skunk (genus Spilogale). Journal of Mammalogy 49:373-390.

Mead, R.A. 1968. Reproduction in western forms of the spotted skunk (genus Spilogale). Journal of Mammalogy 49:373-390. Oechsli, L.M. 2000. Ex-urban development in the Rocky Mountain West: consequences for native vegetation, wildlife diversity, and land-use planning in Big Sky, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 73 p.

Oechsli, L.M. 2000. Ex-urban development in the Rocky Mountain West: consequences for native vegetation, wildlife diversity, and land-use planning in Big Sky, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 73 p. Reid, F. 2006. Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America, 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston and New York, 608 pp.

Reid, F. 2006. Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America, 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston and New York, 608 pp. Rust, H. J. 1946. Mammals of northern Idaho. J. Mammal. 27(4): 308-327.

Rust, H. J. 1946. Mammals of northern Idaho. J. Mammal. 27(4): 308-327. Thompson, L.S. 1982. Distribution of Montana amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. Bozeman: Montana Audubon Council. 24 pp.

Thompson, L.S. 1982. Distribution of Montana amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. Bozeman: Montana Audubon Council. 24 pp. Van Gelder, R.G. 1959. A taxonomic revision of the spotted skunks (genus Spilogale). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 117:229-392.

Van Gelder, R.G. 1959. A taxonomic revision of the spotted skunks (genus Spilogale). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 117:229-392. Verts, B. J., L. N. Carraway, and A. Kinlaw. 2001. Spilogale gracilis. American Society of Mammalogists, Lawrence, KS. Mammalian Species No. 674:1-10.

Verts, B. J., L. N. Carraway, and A. Kinlaw. 2001. Spilogale gracilis. American Society of Mammalogists, Lawrence, KS. Mammalian Species No. 674:1-10. Verts, B.J. 1967. The biology of the striped skunk. Univ. Illinois Press, Urbana. vii+218 pp.

Verts, B.J. 1967. The biology of the striped skunk. Univ. Illinois Press, Urbana. vii+218 pp. Wilson, D. E., and D. M. Reeder (editors). 1993. Mammal Species of the World: a Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Second Edition. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC. xviii + 1206 pp.

Wilson, D. E., and D. M. Reeder (editors). 1993. Mammal Species of the World: a Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Second Edition. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC. xviii + 1206 pp.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Western Spotted Skunk"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Mammals"