View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

European Common Reed - Phragmites australis ssp. australis

Other Names:

Common Reed

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Phragmites australis subspecies australis was introduced into Canada and the USA where it has become an invasive species (Flora of North America 2007). In Montana, Phragmites australis subspecies australis was first detected in 2014 in Blaine and Hill counties, and by 2015, the Montana Department of Agriculture listed subspecies australis as a noxious weed (MDA 2017). Populations occur in wetlands or ditches along railroad tracks and roads (Lesica et al. 2022). Populations form large, dense monotypic stands that outcompete native plant species and can alter ecosystem functions (Gucker 2008). Newer occurrences have been documented in Flathead, Gallatin, and Missoula counties. The Montana Department of Agriculture works collaboratively with the counties to actively monitor and control populations, and efforts are proving successful. A conservation status rank is not applicable (SNA) because non-native plants are not a suitable target for conservation activities.

The Montana Natural Heritage Program tracks Phragmites australis at the subspecies (subsp.) level because subsp. americanus is native while subsp. australis is introduced in the state. In reporting information on Phragmites australis, it is important to identify plants at the subspecies level in order to facilitate accurate identifications, data collecting, and appropriate management actions.

General Description

PLANTS: A cool season, rhizomatous perennial grass. Stems are stout, erect, and hollow, forming dense, tall stands of 1.5-3.5 meters tall. Sources: Gucker 2008; Lesica et al. 2022

LEAVES: Blades are flat, 315-40 cm long, and 2–4 cm wide, flat and lax to ascending. Sheaths have overlapping margins. Ligules are hairy, 3–6 mm long. Auricles are lacking. Sources: Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018; Lesica et al. 2022

INFLORESCENCE: A large feathery (plumose) panicle, 15–32 cm long, and often purplish. Spikelets, 11–14 mm long, with 3 to 8 florets. Rachilla with numerous long, silky hairs that cover the spikelets. Glumes are 1-3 nerved, rounded on the back; the 2nd glume is longer than the 1st glume, but shorter than 1st lemma. Lemmas are 3-nerved, rounded on the back, hairless, and with an awn-like tip. Palea is well developed. Florets are the unit of dispersal, disarticulating above the glumes. Sources: Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018; Lesica et al. 2022

SUBSPECIES australis: Ligule usually 0.1-0.4 mm long. 1st (lower) Glume 2.5-4.0 mm long. 2nd (upper) Glume 4.5-7.5 mm long. Leaf Sheath is usually persistent.

Phenology

Across its range, flowers and fruits develop from July to November (Gucker 2008). European Common Reed tends to emerge earlier than American Common Reed (Gucker 2008).

Diagnostic Characteristics

European and American subspecies of

Phragmites australis can grow in patches adjacent to one another (MSUE no date).

They can be distinguished by examining the characteristics of the lower stem, ligules, and lemmas

across a given population (

not just from a few stems):

* Ligule: The membranous extension where the leaf sheath and leaf blade meet. On the middle leaves, measure the membranous portion, not the fringe of hairs.

* Glumes: At the base of each spikelet is a pair of bracts called glumes.

Subspecies australis - European Common Reed,

not native and undesirable

* Growth Form: Robust – reaching up to 18 meters in places within the USA. Stands outcompete native plant species.

* Culms: Leaf sheaths cling tightly to the stem. Remove the lower leaf sheaths and find a yellow to yellow-brown stem that stays dull into the growing season.

* Ligule: Membrane, 0.1 – 0.4 mm tall.

* Glumes: 1st (lowest) glume is shortest, 2.6-4.8 mm long; 2nd glume is longer, but shorter than the lemma.

* Lemma: 6.4-8.7 mm long.

Subspecies americanus - American Common Reed, native and desirable

* Growth Form: Relatively less robust - typically reaching 6 feet. Stands often have space for other plants to colonize.

* Culms: Often Leaf sheaths fall prematurely with age (caducous). When exposed to sunlight the stem turns bright red to purplish. Stems stay shiny late into the growing season.

* Ligule: Membrane, 0.2 – 0.9 mm tall.

* Glumes: 1st (lowest) glume is shortest, (2.6)4-7 mm long; 2nd glume is longer, but shorter than the lemma.

* Lemma: 9.3-9.9 mm long.

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Non-native

Non-native

Range Comments

Phragmites australis subsp. australis, European Common Reed, is an introduced grass from Eurasia and Africa. It was introduced into the US through at least 1 or more ports during the 19th century, pre-1910 (Gucker 2008). The introductions went unnoticed because the morphological differences between subspecies are subtle. The construction of travel systems is likely what allowed European Common Reed to spread (Gucker 2008). European Common Reed occurs from British Columbia to Quebec in Canada. And south throughout the contiguous United States (Gucker 2008; Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018).

COLONIZATION AND EXPANSION

Since its introduction, European Common Reed has outcompeted the American Common Reed and established itself in the southeast where the species was historically absent (Gucker 2008). By 1940 all representation of the native subspecies in Massachusetts and Connecticut had disappeared, replaced by the non-native subspecies (Gucker 2008). In Canada, the European Common Reed was documented as early as 1916, where it was regarded as rare until the 1970s (Gucker 2008). Since the 1970s, and in less than a 20-year time span, European Common Reed became common in linear wetlands, industrial areas, and right-of-ways in southern Quebec (Gucker 2008). The intrinsic rate of increase ranged from 0.19 per year to 0.34 per year in St-Bruno-de-Montarville and 0.54 on Laval Island (Gucker 2008). Further, European Common Reed was more prevalent in anthropogenic wetlands than in riparian habitats (Gucker 2008).

By the late 1990s, European Common Reed was described as “widespread” or as a “nuisance species” in tidal wetlands of North America (Chambers et al. 1999). Researchers have suggested that the establishment and spread was facilitated by increased temperatures and decreased water levels in the mid- to late-1990s. Readers wanting more information should consult the USFS, Fire Effects Information System for Phragmites australis by Gucker (2008).

In Montana, plants have been documented in Blaine, Flathead, Gallatin, Hill, Missoula counties. The first documented occurrence was found in Blaine and Hill Counties in 2014. Upon verifying the identification with genetic testing, the Montana Department of Agriculture in cooperation with the counties has been actively controlling populations.

For maps and other distributional information on non-native species see:

Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Habitat Tool (INHABIT) from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Compendium from the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI)

EDDMapS Species Information EDDMapS Species Information

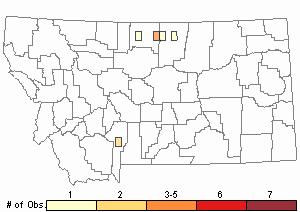

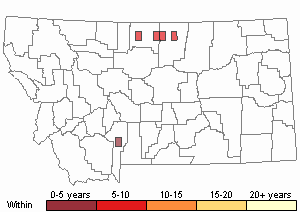

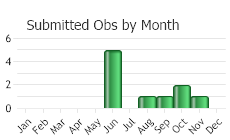

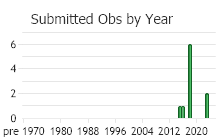

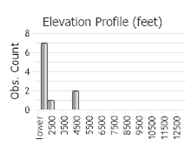

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 12

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

In Montana, European Common Reed is found at the margins of ponds, marshes, and river floodplains and in roadside ditches et al. (Lesica et al. 2022). It has been collected along railroad tracks and roads (Lesica et al. 2022).

Ecology

Readers should also consult the species’ profile for Common Reed (

Phragmites australis).

PLANT-WILDLIFE INTERACTIONSCommon Reed provides habitat for aquatic species, though, the non-native European Common Reed alters the ecology of aquatic systems.

PLANT SPECIES COMPETITION [Adapted from MSUE (no date) and Gucker 2008]

Several aspects of European Common Reed allow it to outcompete native plant species. The stems produce above-ground stolons and below-ground rhizomes, which creates a denser stand, resulting in a monoculture. Stolons are usually produced during environmental conditions of low water. The (vertical) stems don’t easily break down which leads to an accumulation of litter, creating a thick thatch. The stiff, narrow ligule is thought to contribute to its hardiness in helping the leaves to remain on the culm.

Reproductive Characteristics

European Common Reed reproduces sexually by seed, and vegetatively by rhizomes and stolons.

Readers should also consult the species’ profile for Common Reed (

Phragmites australis).

STOLONS [Adapted from MSUE (no date) and Gucker 2008]

Stolons are horizontal above-ground stems. They can be red for European Common Reed plants, even though the vertical stems are not (MSUE no date). Stolons of European Common Reed have been known to reach lengths of 43 feet.

LIFE CYCLE [Adapted from Gucker 2008]

A stand of European Common Reed is composed of culms (vertical stems) growing from stolons or rhizomes that are sourced from the same genetic material; the stems are clones. Stands are long-lived, but no portion of the clone lives for more than 8 years.

Plants expand populations predominantly through rhizomes and stolons. Plants disperse to new locations by seeds, rhizomes, stolons, and sod fragments.

PLANT BIOLOGYIn comparison to the American Common Reed, European Common Reed plants emerge earlier, produce more biomass, and activate dormant rhizome buds more readily.

Economic Value

Readers should consult the species’ profile for Common Reed (

Phragmites australis).

Management

Readers should consult the species’ profile for Common Reed (

Phragmites australis).

INTEGRATED VEGETATION MANAGEMENTEuropean Common Reed is an invasive plant. Its establishment, spread, and increase in abundance are associated with human-caused disturbances, such as from land development, tidal manipulation, and waterway construction. An integrated vegetative management approach provides the best long-term control and requires that land-use objectives and a desired plant community be identified (Shelly et al. in Sheley and Petroff 1999). Once identified, an integrated weed management strategy that promotes a weed-resistant plant community and serves other land-use objectives such as livestock forage, wildlife habitat, or recreation can be developed. Further, it is imperative to understand the biological, chemical, and physical impacts at the particular site in order to determine the management strategy and process (Gucker 2008).

ECOSYSTEM ENGINEERIn portions of the USA, European Common Reed has been called an "ecosystem engineer" because dense, monotypic stands can change plant richness, soil properties, sedimentation rates, animal habitat use, and food webs (Gucker 2008). Large stands of European Common Reed have decreased plant diversity due to its growth form, ability to trap sediment, and accumulate reed leaf litter. In New Jersey, European Common Reed stands have lowered water salinity, depth to water table, and topographic relief when compared to stands dominated by Saltmeadow Cordgrass and Saltgrass in brackish tidal marshes (Gucker 2008). Further these changes were determined to be significant just after three years of European Common Reed establishment.

PREVENTIONLarge, monocultures of European Common Reed can be prevented through management actions that encourage competing vegetation and minimize nutrient loads (Gucker 2008). European Common Reed spreads faster in areas with high-nutrient availability, particularly where competing vegetation has been removed or reduced. The timing and intensity of hydrological changes can impact European Common Reed stands.

FIREReaders wanting more information on fire effects should consult Gucker (2008).

Prescribed fire is not recommended for controlling European Common Reed. Plants grow in wet environments which are often poorly affected by fire and where other native plants are not adapted to fire. European Common Reed plants may be top-killed by fire, but their rhizomes usually survive and will re-sprout (Gucker 2008). Unless rhizomes are killed, fire can stimulate re-sprouting (Gucker 2008). In the short-term, fire may decrease plants, but if viable rhizomes remain than stands will re-colonize (Gucker 2008).

Common Reed provides nesting habitat to numerous waterfowl species. Fires can negatively impact nesting birds if timed incorrectly. Studies during the 1960s and 1970s found that spring fires should be conducted before April 20th to miss the beginning of Mallard (

Anas platyrhynchos)and Northern Pintail (

Anas acuta) nesting (Gucker 2008). Summer fires should be conducted after Gadwall (

Mareca strepera) and Blue-winged Teal (

Spatula discors) have left their nests (Gucker 2008).

CHEMICAL CONTROLSHerbicides are effective for control in Montana. The application of appropriate herbicides are most effective when carefully planned, timed, and incorporated with long-term control tactics that include replacing weeds with desirable plant species, modifying land use management, monitoring and implementing follow-up control, and preventing new infestations.

The Montana Department of Agriculture works with many collaborators to monitoring and effectively control populations. The following information was provided in 2025 (Wagoner, personal communication); however, readers should directly consult the department for current information as this profile is not frequently updated:

Hill/Blaine Counties: After a decade of treatment the infestation declined from about 4 acres to 0.2 acres. Due to the large amount of biomass, the site was burned and then treated with the herbicide, glyphosate plus imazapyr. The method is slowly effective with a reduction in plant number, density, and height.

Gallatin County: Plants were found at two locations collectively covering about 0.2 acre. Plants were clipped, bagged, and the seedheads incinerated at both sites. One site was excavated then paved over while the other site was treated with glyphosate herbicide. Both are being actively monitored, and at the later site cattails are spreading back into where European Common Reed was present.

Useful Links:Central and Eastern Montana Invasive Species TeamMontana Invasive Species websiteMontana Biological Weed Control Coordination ProjectMontana Department of Agriculture - Noxious WeedsMontana Weed Control AssociationMontana Weed Control Association Contacts WebpageMontana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks - Noxious WeedsMontana State University Integrated Pest Management ExtensionWeed Publications at Montana State University Extension - MontGuidesStewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

European Common Reed readily establishes, spreads, and increases in dominance, especially in association with anthropogenic disturbances, such as land development (residential and transportation), waterway construction, and tidal manipulation (Gucker 2008). The spread of European Common Reed is attributed to the construction of railroad, road corridors, and waterways, manipulation of water levels, and other factors. Areas in the Great Lakes region and along the Atlantic Coast have been negatively impacted the most.

The conversion of wetlands to dense, monotypic stands of European Common Reed has altered native plant diversity, soil properties, sedimentation rates, bird and fish habitat use, and food webs (Gucker 2008). Large, dense populations of the reed modify or reduce the mosaic of microhabitats in a wetland that are necessary to retain a diversity of (native) fish, plant, and wildlife populations. The introduced reed outcompetes native plants because it grows fast and dense, physically reducing space for other plants, and sequestering more nutrients from the soil. As reed densities increase, it builds up a thick layer of plant litter, which has a slow decay rate and elevates the ground surface, dries out the wetland, and changes the environmental conditions for other plant species that had previously occupied the site. The greater biomass of accumulated plant litter also changes the wetland's water levels and flow patterns, reduces or modifies nutrient availability, and alters salinity levels that are sourced by natural flooding cycles. European Common Reed can also eliminate small intertidal channels and obliterate pool habitat that offers a refuge and feeding grounds for aquatic invertebrates, fish, amphibians, and water birds (USFWS 2007). Through plant succession, the colonization of European Common Reed can change a site from wetland to meadow or forest (Gucker 2008). In wetland tidal systems, European Common Reed is usually an indicator of an ecosystem imbalance.

Large, dense European Common Reed populations also limit recreational activities for birdwatchers, fisherman, and hunters (USFWS 2007). They can choke out waterways that were previously accessible by boat, canoe, and kayak.

Large, dense reed populations can also alter fire ecology. The development of large, dense monotypic stands can dry a site and the build up of plant litter can fuel a fire. Thus, fire danger can increase in residential and commercial areas that have large stands of European Common Reed (USFWS 2007).

Since 2014, Montana has a small, but growing number of locations where European Common Reed occurs. Various control efforts by the Montana Department of Agriculture, county weed departments, and other entities have been and continue to be implemented.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 2007. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Volume 24. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae, Part 1. Oxford University Press, Inc., NY. xxxiii + 911 pp.

Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 2007. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Volume 24. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae, Part 1. Oxford University Press, Inc., NY. xxxiii + 911 pp. Flora of North America Editorial Committee. 2003. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 25. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae (in part): Poaceae, part 2. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. xxv + 781 pp.

Flora of North America Editorial Committee. 2003. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 25. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae (in part): Poaceae, part 2. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. xxv + 781 pp. Gucker, Corey L. 2008. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS) for Phragmites australis. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). [Accessed 23 March 2018]

Gucker, Corey L. 2008. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS) for Phragmites australis. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). [Accessed 23 March 2018] Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Second Edition. Giblin, D.E., B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead (eds). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 882 p.

Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Second Edition. Giblin, D.E., B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead (eds). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 882 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Michigan State University Extension. No Date. Phragmites australis identification pamphlet for subspecies. East Lansing, Michigan.

Michigan State University Extension. No Date. Phragmites australis identification pamphlet for subspecies. East Lansing, Michigan.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "European Common Reed"