View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Common Reed - Phragmites australis

Other Names:

Phragmites communis

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Phragmites australis is a grass found on all continents, except for Antarctica (Allred in Flora of North America 2003). In Canada and the USA, Phragmites australis is represented by at least three ecologically and genetically distinct subspecies (Catling et al. 2004; Salstonstall 2002; Salstonstall et al. 2004; Flora of North America 2007). As of 2022, individuals from the native lineage, subspecies americanus, and the introduced lineage, subspecies australis are found in at least 25 of Montana’s 56 counties. The two subspecies can be distinguished based on morphology and are tracked separately by the Montana Natural Heritage Program. In reporting information on Phragmites australis, it is important to identify plants at the subspecies level in order to facilitate accurate identifications, data collecting, and appropriate management actions. A conservation status rank at the species level ranges from S4 to Status Not Applicable (SNA).

General Description

PLANTS: A cool season, rhizomatous perennial grass. Stems are stout, erect, and hollow, forming dense, tall stands of 1.5-3.5 meters tall. Sources: Gucker 2008; Lesica et al. 2022

LEAVES: Blades are flat, 315-40 cm long, and 2–4 cm wide, flat and lax to ascending. Sheaths have overlapping margins.

Ligules are hairy, 3–6 mm long. Auricles are lacking. Sources: Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018; Lesica et al. 2022

INFLORESCENCE: A large feathery (plumose) panicle, 15–32 cm long, and often purplish.

Spikelets, 11–14 mm long, with 3 to 8 florets. Rachilla with numerous long, silky hairs that cover the spikelets.

Glumes are 1-3 nerved, rounded on the back; the 2nd glume is longer than the 1st glume, but shorter than 1st lemma.

Lemmas are 3-nerved, rounded on the back, hairless, and with an awn-like tip.

Palea is well developed. Florets are the unit of dispersal, disarticulating above the glumes. Sources: Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018; Lesica et al. 2022

Montana has two subspecies:

americanus [native lineage] and

australis [introduced lineage].

TAXONOMY & NOMENCLATUREPhragma is Greek for ‘fence’, in reference to the plant’s ability to create dense stands (Giblin et al. [eds.] 2018).

Phenology

Across its range, flowers and fruits develop from July to November (Gucky 2008).

Diagnostic Characteristics

Phragmites australis is the tallest grass in Montana. It is easily distinguishable by its tall stature and feathery or plumose inflorescence. Montana’s plants represent two ecologically and genetically distinct subspecies, which are tracked separately by the Montana Natural Heritage Program.

* American Common Reedgrass, subspecies

americanus is native to Montana.

* European Common Reedgrass, subspecies

australis is exotic (non-native) to Montana.

Sterile specimens of

Phragmites are superficially similar to Arundo, but can be distinguished by their glumes (Lesica et al. 2012). Arundo is an invasive grass in the USA, but is not documented in Montana.

*

Phragmites - Common Reed - has glabrous glumes that are shorter than the lemmas.

*

Arundo - Giant Reed - has glumes covered with soft, whitish hairs of 6-8 mm long that are longer than the lemmas.

Range Comments

Phragmites australis is found on every continent except Antarctica and may have the widest distribution of any flowering plant (Tucker 1990). Globally, the species is common in and near freshwater, brackish and alkaline wetlands in the temperate zones. It may also be found in some tropical wetlands but is absent from the Amazon Basin and central Africa.

In Montana, Phragmites australis is found in most counties, particularly in the western, southern, and northern portions of the state (Lesica et al. 2022).

For maps and other distributional information on non-native species see:

Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Habitat Tool (INHABIT) from the U.S. Geological Survey

Invasive Species Compendium from the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI)

EDDMapS Species Information EDDMapS Species Information

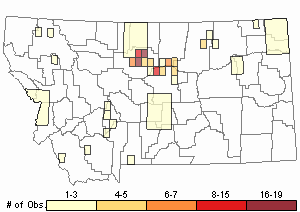

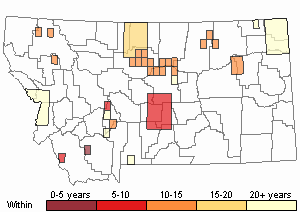

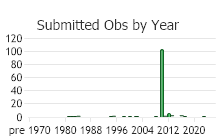

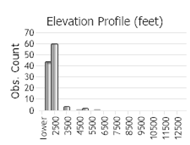

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 135

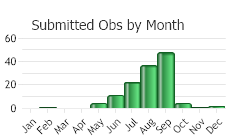

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Worldwide, Common Reed grow in saline or freshwater wetlands (Allred in FNA 2003). Plants are widespread in the United States, typically growing in marshes, swamps, fens, and prairie potholes, and often inhabiting the marsh-upland interface where it may form continuous belts (Roman et al. 1984).

In Montana, plants are found at the margins of ponds, marshes, and river floodplains, and in roadside ditches (Lesica et al. 2022).

Ecology

NOTE: Literature compiled by Gucky (2008) for Phragmites australis is comprehensive, but many of the publications report information on populations in which the subspecies was not identified. Many were published before the morphological differences between American and European subspecies were understood.

PLANT-WILDLIFE INTERACTIONSCommon Reed provides food, cover, roosting, and nesting habitats for small mammals, muskrats, waterfowl, rabbits, pheasants, songbirds, and numerous other animals. (Gucker 2008). The type and the degree of use by native birds and mammals seems to reflect geography, species, and availability of other resources. For species-specific information and references, consult Gucker 2008.

Young Common Reed grass is considered palatable for livestock and native ungulates (Gucker 2008). Nutritionally, the grass is considered to be a fair food source for Pronghorns (

Antilocapra americana) and a poor food source for Mule Deer (

Odocoileus hemionus, White-tailed Deer (

Odocoileus virginianus), and Elk (

Cervus canadensis) in Montana. Palatability is considered fair for horses and cattle, and poor for sheep. However, the nutritional value differs by geography, for species, and likely by other factors.

Common Reed provides good thermal cover for White-tailed and Mule Deer species.

Common Muskrats (

Ondatra zibethicus) feed on rhizomes and culms, and also use the culms for nesting material.

Depending upon the bird species, Common Reed may provide food, nesting material, and roosting and hunting habitats, and also may harbor insects that become food for birds. In Montana, Red-winged (

Agelaius phoeniceus) and Yellow-headed (

Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus) Blackbirds feed on the seeds. For ducks, Common Reedgrass is not an important food source, but does provide good nesting habitat. In the prairie-pothole region, the larger stands of Common Reed can be important to habitats for flightless, molting adult ducks. Black-capped chickadees (

Poecile atricapillus) and other birds eat the scales (

Caetococcus phragmitidis) that commonly live on the plant’s leaf sheaths.

In other regions various songbirds, Barn Owls (

Tyto furcata), Short-eared Owls (

Asio flammeus), Chimney Swifts (

Chaetura pelagica), Barn Swallows (

Hirundo rustica), and Red-tailed Hawks (

Buteo jamaicensis) may use stands for foraging and/or roosting.

Plants may also provide habitat for aquatic species; although, the non-native subspecies, australis, can also change the ecology of aquatic systems.

PLANT SUCCESSIONCommon Reed is both a pioneer and a climax species (Gucker 2008). In natural freshwater systems, Common Reed is considered an early colonizer, but in saline systems, like salt marshes, it colonizes later (Gucker 2008). Common Reed often establishes at later ecological stages in open water of deep swamps, lakes, ponds, and swales - after both the initial development of submerged plants, such as watermilfoil (

Myriophyllum) and/or bladderwort (Utricularia) and the secondary development of floating-leaved plants (Nymphaea, Ranunculus, Potamogeton) (Gucker 2008). Eventually, swamps and other wetlands may succeed to meadows or deciduous forests.

Where the habitat is disturbed, Common Reed readily colonizes, especially the introduced subspecies. If present at the site before disturbance, plants easily grow back from its below ground rhizome (Gucker 2008). Where plants are absent, colonization usually occurs where soils are barren (Gucker 2008).

PLANT COMPETITION

In New York, Common Reed produced almost twice the amount of above-ground biomass and sequestered a significantly greater amount of nitrogen and phosphorus into its tissues than did Narrow-leaved Cattail (Typha angustifolia) and Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria).

HYDROLOGY and SALINITY

Common reed tolerates frequent flooding, both seasonally and prolonged (Gucker 2008). Plants also tolerate seasonal drying. Plants grow best in fresh water or water with low salinity (under 5,000 parts per million). The cover, stem height, and percentage of flowering stems were significantly negatively correlated with salinity (Gucker 2008).

CLIMATE

Common Reed appears to be climatically tolerant of many conditions. In North America it occurs from semi-arid to arid desert, sub-humid to humid continental, to subtropical climates. In Nebraska, plants were found to roll their leaves inward during drought. Rolled leaves have less exposure to air and solar radiation, and is a way for the grass to reserve moisture or prevent water loss.

Reproductive Characteristics

Common Reed reproduces sexually by seed. Common Reed also reproduces vegetatively by rhizomes and/or stolons, depending upon the subspecies. Please note that most of the scientific literature referenced in Gucker (2008) either focused on the introduced European Common Reed or did not specify the focal subspecies.

FLOWERS [Adapted from Gucker 2008]

A single inflorescence produces flowers that are either unisexual or bisexual. Within the spikelet, the lower florets tend to be staminate (pollen-producers) or sterile while the upper florets have both sexes, producing egg and pollen, or are also sterile.

STOLONS [Adapted from MSUE (no date) and Gucker (2008)]

Stolons are horizontal above-ground stems, produced only by the introduced European Common Reed. Regenerative growth occurs less often through stolons (as compared to rhizomes).

RHIZOMES [Adapted from Gucker 2008]

Rhizomes are horizontal below-ground stems. European Common Reed has thick, scaley rhizomes that can grow to 70 feet long. The depth, structure, and sizes of European Common Reed rhizomes are partially a function of site conditions. In the eastern states, rhizomes typically grow at depths of 4 to 8 inches, but a wetland in Nebraska found rhizomes to the depth of 30 feet. A single rhizome lives for 2 to 3 years. In Britain, a study found rhizomes in their first-year to produce 1 vertical stem (culm), in their second-year to produce 4 culms, and in their third-year to produce 6 culms. Further rhizomes of 6 or more years old produced fewer culms.

Regenerative growth occurs more often through rhizomes. Fragmented rhizomes can spur growth and establishment. Rhizomes growing in soil typically grow thick, long, and unbranched. Rhizomes growing in water tend to be shorter, slender, and highly branched. At the nodes, a cluster of hair-like roots develop. In the east, buried rhizomes have better survival than those left on the soil surface. Buried rhizomes survive better than seeds. In general, regenerated plants from rhizomes are hardier than individual young plants that grow from seed.

Factors that reduce the establishment of Common Reed from fragmented rhizomes include high levels of salinity of at least 18,000 parts per million, anoxic conditions, and small rhizome sizes.

LIFE CYCLE [Adapted from Gucker 2008]

Readers wanting more information on seed viability, dispersal, germination, and banking should consult Gucker (2008).

A stand of European Common Reed is composed of culms (vertical stems) growing from stolons or rhizomes (both horizontal stems) which are sourced from the same genetic material; the stems are clones. Stands are long-lived, but no portion of the clone lives for more than 8 years. Plants expand from existing populations predominantly through rhizomes and stolons. Plants disperse to new locations by seeds, rhizomes, stolons, and sod fragments. Along waterways, streambank erosion from storms, high water, and other events, can cause rhizomes and sod to fragment, be carried downstream, and re-establish where suitable conditions occur. Overall, Common Reed plants survive and also grow better in fresh than saline water.

Flowers produce seeds primarily through cross-pollination, though self-pollination or agamospermy (seed production without fertilization) can occur. Seed viability has been reported as highly variable and ranging from little to abundant. It seems that vegetative reproduction is more prominent for the species. Seeds are dispersed by wind and water. Seeds collected from Germany and the Netherlands found that their buoyancy was greater in moving water than in stagnant water. Seeds germination generally occurs on mineral soil, but seedling survival is low.

Submersion often reduces germination but does not necessarily result in a loss of seed viability. Germination is often greatest where soils are not flooded. Germination tends to decrease in flooded conditions. However, a short period of submersion may increase germination rates. Germination success increases under conditions of warm temperatures, high light, and low to moderate salinity levels on moist but not flooded sites.

GROWTH [Adapted from Gucker 2008]

Both above- and below-ground parts of European Common Reed are capable of fast growth. Plants grow best where there is high light. Plant height and density were reported as being lower in partial shade.In Wisconsin Common Reed wash found to grow 16 inches in a single year. In Massachusetts, plants were calculated to spread over 33 feet in a single year on a bare sandy dredge.

Plants can also alter their environment to facilitate growth – and they grow better where sulfide concentrations are none to low. Where sulfide levels were lower, plant growth was higher. Experiments led researchers to suggest that the plant lowers sulfide concentrations in a marsh by oxygenation and possibly also by pressurized ventilation of the rhizosphere. Further a plant provided essential nutrients from well-established culms through it rhizomes to colonizing culms. Allelopathy has not been found in Common Reed.

Economic Value

CULTURAL USESPeople, across numerous cultures, ethnicities, and tribes have found multiple uses for Common Reed. Common Reed played a vital role in the lives of Native American peoples and colonists. In North America and prior to the 1900s people would have relied on the native American Common Reed, subspecies

americanus. This reliance continued after the 1900s, and would have included the introduced European Common Reed, subspecies

australis, which largely went unnoticed, but greatly expanded the distribution of 'reed grass'. For people living in the southern USA, Mexico, and Central America uses of Common Reed would likely have also included a Gulf Coast lineage, treated by FNA (2007) as variety

berlandieri - but not known north of Southern California, Arizona, and New Mexico.

Broadly speaking, Common Reed was used by Native American peoples for foods, shelter, medicines, a great variety of tools, and spiritual practices (Gucky 2008). Colonists and settlers also used American Common Reed for foods, shelter, and tools of many kinds. For information and references about how specific Native American peoples, consult Gucker 2008. For additional information on cultural uses consult the species’ profile for Common Reed (

Phragmites australis).

Food and MedicinesThe seeds serve as a grain used in gruels, cereals, and breads (Kavasch 2005). The early shoots serve as a raw or cooked vegetable (Kavasch 2005). The roots and rhizomes provided year-round food, and were dug and roasted (Kavasch 2005). The stems serve as an excellent source of sugar (Kavasch 2005). Preparations of materials from Common Reed has been used to treat stomach, ear, and tooth pains, lung ailments, and diarrhea (Gucky 2008).

Shelter, Tools, & Other UsesCommon Reed is used in the construction of items used for food gathering, warfare, travel, relaxation, and spiritual practices (Gucky 2008). Items included fences, roofs (thatching), lattices, baskets, pipestems, arrow shafts, construction boards, mats and insulation, nets, prayer sticks, and erosion control (Allred

in FNA 2003; Kavasch 2005; Gucky 2008). Plants have been but are no longer used to make cigarettes and 'superior' pen quills (Allred

in FNA 2003). Plants are also used for fuel, fertilizer, and mulch (Gucky 2008). The large feathery panicles persist into winter and are valued for winter bouquets (Lescia et al. 2022).

Management

Management of Phragmites australis depends upon the subspecies.

It is important to accurately identify the subspecies before implementing any management action. In Montana, land managers are encouraged to maintain native common reed populations while eradicating non-native populations. It is recommended that Phragmites australis management be site-specific, goal-specific, and value-driven (Gucker 2008). Further, it is imperative to understand the biological, chemical, and physical impacts at the particular site in order to determine the management strategy and process.

The establishment, spread, and population increase of the non-native European Common Reed (

Phragmites australis subsp.

australis) is associated with human-caused disturbances, such as from land development, tidal manipulation, and waterway construction.

RECLAMATIONThe native, American Common Reed has attributes (rhizomatous and dense growth form) that make can make it desirable in reclamation projects, such as for controlling erosion. It is imperative that only the certified, native American Common Reed from Montana populations be seeded or planted. American Common Reed has the ability to create small, nearly monoculture stands that occur in a matrix with other native plant communities; further, the stand creates enough openings to allow other plants to co-exist.

ECOSYSTEM ENGINEERIn portions of the USA, the non-native European Common Reed has been called an "ecosystem engineer" because it can form dense, monotypic stands that change plant richness, soil properties, sedimentation rates, animal habitat use, and food webs (Gucker 2008). Large stands of European Common Reed have decreased plant diversity due to its growth form, ability to trap sediment, and accumulate reed leaf litter. In New Jersey, European Common Reed stands have lowered water salinity, depth to water table, and topographic relief when compared to stands dominated by saltmeadow cordgrass and saltgrass in brackish tidal marshes (Gucker 2008). Further these changes were determined to be significant just after three years of European Common Reed establishment.

In many parts of the U.S. large monocultures of the non-native European Common Reed has warranted management actions that includes altering hydrology, herbicide application, applying fire, planting competitive vegetation, and other tactics.

LIVESTOCK & WILDLIFE FORAGEYoung Common Reed grass is considered palatable for livestock and native ungulates. See Ecology section. Plants can provide an important barrier that limits grazing animals and humans relative to marsh-inhabiting native wildlife.

Useful Links:Central and Eastern Montana Invasive Species TeamMontana Invasive Species websiteMontana Biological Weed Control Coordination ProjectMontana Department of Agriculture - Noxious WeedsMontana Weed Control AssociationMontana Weed Control Association Contacts WebpageMontana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks - Noxious WeedsMontana State University Integrated Pest Management ExtensionWeed Publications at Montana State University Extension - MontGuidesStewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Threats and limiting factors are addressed at the subspecies level in their respective profiles on the Montana Field Guide.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 2007. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Volume 24. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae, Part 1. Oxford University Press, Inc., NY. xxxiii + 911 pp.

Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 2007. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Volume 24. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae, Part 1. Oxford University Press, Inc., NY. xxxiii + 911 pp. Flora of North America Editorial Committee. 2003. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 25. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae (in part): Poaceae, part 2. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. xxv + 781 pp.

Flora of North America Editorial Committee. 2003. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Vol. 25. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae (in part): Poaceae, part 2. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. xxv + 781 pp. Gucker, Corey L. 2008. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS) for Phragmites australis. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). [Accessed 23 March 2018]

Gucker, Corey L. 2008. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS) for Phragmites australis. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). [Accessed 23 March 2018] Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Second Edition. Giblin, D.E., B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead (eds). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 882 p.

Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Second Edition. Giblin, D.E., B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead (eds). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press in Association with Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 882 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2012. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 771 p. Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p.

Lesica, P., M.T. Lavin, and P.F. Stickney. 2022. Manual of Montana Vascular Plants, Second Edition. Fort Worth, TX: BRIT Press. viii + 779 p. Michigan State University Extension. No Date. Phragmites australis identification pamphlet for subspecies. East Lansing, Michigan.

Michigan State University Extension. No Date. Phragmites australis identification pamphlet for subspecies. East Lansing, Michigan.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Hale, K.M. 2007. Investigations of the West Nile virus transmission cycle at Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge, Montana, 2005-2006. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 74 p.

Hale, K.M. 2007. Investigations of the West Nile virus transmission cycle at Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge, Montana, 2005-2006. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 74 p. Mathews, S.L. 1995. Evolution of the phytochrome gene family in land plants and its utility for phylogenetic analyses of flowering plants. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 85 p.

Mathews, S.L. 1995. Evolution of the phytochrome gene family in land plants and its utility for phylogenetic analyses of flowering plants. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 85 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Common Reed"