View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Western Glacier Stonefly - Zapada glacier

Other Names:

Glacier Forestfly

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

The Western Glacier Stonefly is listed Threatened under the US Endangered Species Act in 2019. The species rank is "S1" in Montana because of its high risk of extirpation due to very limited and/or potentially declining population numbers, range and/or habitat. This species is particularly vulnerable due to its very restricted habitat in cold water (<8.0°C). This species is one of 7 species of globally rare insects within Glacier National Park that may be adversely affected when the glaciers have completely melted.

General Description

Adults are 6.5-10.0 mm in length and brown with wings nearly as long or longer than the body (Baumann and Gaufin 1971). Adults fold their wings over their back and have antenna much longer than their head. Nymphs are a similar length but lack wings and are aquatic (L. Tronstad, personal observation). Zapada glacier nymphs have gills on their neck (cervical gills) and late instars are darkly colored. Zapada glacier can be separated from Lednia tetonica by the presence of cervical gills; however, nymphs of Zapada cannot be identified to species at this stage using body characters.

Phenology

Zapada glacier lives most of their lives (~1 year) in the water as nymphs (wingless, immature insects) and emerge as winged adults in July or August to find a mate and reproduce (Baumann et al. 1977; L. Tronstad, personal observation). Adult Zapada glacier are short lived (probably a week or less), making them difficult to collect in this life stage. They likely have poor dispersal as most stonefly adults are weak fliers.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Larvae have not been associated with the adults or distinguished from other

Oregon Forestfly, (

Z. oregonensis) group species, although they share the typical characters of the group: cervical gills simple, unbranched and not constricted past the base. Thus, this species would not be identified to species and left within this species group level by taxonomy labs identifying bioassesment samples. Adults described in Baumann and Gaufin (1971).

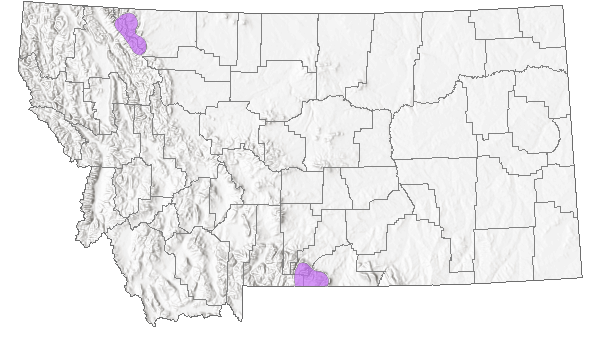

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Range Comments

Zapada glacier was discovered in Glacier National Park in 1964 in Cataract Creek below Grinnell Glacier and found in 4 other streams in subsequent years (Baumann and Gaufin 1971), but is currently known from 5 streams (Giersch et al. 2015, Hotaling et al. 2019). Zapada glacier was reported in Wyoming during 2015 (Giersch et al. 2015) and is known from 5 streams in Grand Teton National Park and the adjacent Jedidiah Smith Wilderness in Wyoming (Hotaling et al. 2019; L. Tronstad, unpublished data). Additionally, the stonefly was discovered in 4 streams in the Beartooth Range of Montana (Hotaling et al. 2019) and 8 streams in the Wind, Absaroka, and Beartooth Mountains of Wyoming (Tronstad et al. 2022).

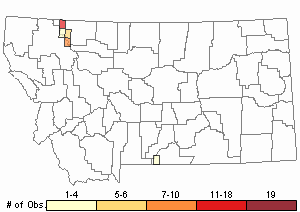

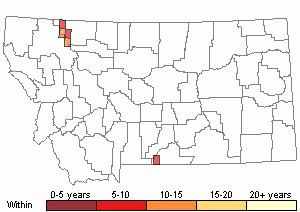

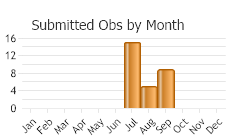

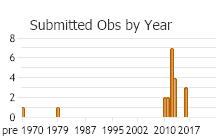

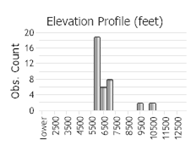

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 42

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Habitat

Zapada glacier lives in streams with cold water temperatures (<8.0°C) that often originate from glaciers or subterranean ice (e.g., rock glaciers) although in Glacier National Park they also live in a high-elevation groundwater-fed streams (Tronstad et al. 2020; Giersch et al. 2016). These stoneflies live in stable streams (i.e., low variation in flow, not flashy) with cobble substrate in the alpine zone of mountains (i.e., above treeline generally). One study suggested they can persist in areas after glaciers have melted (Muhlfeld et al. 2020); however, rock glaciers are very common and cryptic features on the landscape that are the source of streams with very cold, and stable conditions (Brighenti et al. 2021).

Food Habits

Stable isotope analysis in the Teton Range estimated that Zapada glacier ate biofilm (mixture of bacteria, fungi and algae growing on rocks) and the golden algae, Hydrurus (Jorgenson 2022). The proportion of food items consumed depended on their availability and the type of streams that the stonefly lived in (e.g., surface glacier or rock glacier). These stoneflies ate less coarse particulate organic matter (e.g., leaves; 21% on average).

Reproductive Characteristics

Adults have been collected in July (Baumann et al. 1977) and early August in the Teton Range (L. Tronstad, personal observation).

Management

On October 4, 2016 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed listing the Western Glacier Stonefly under the Endangered Species Act due to primary threats to the habitat and range of this species including climate change, loss of glaciers and permanent snowfields, and changes in stream flow and water temperature. On November 21, 2019 a notice was published in the Federal Register that the species' status was determined to be Threatened. Further information on status can be found on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's

Species Account.

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Zapada glacier lives in streams originating from subterranean ice (e.g., rock glaciers) and surface glaciers. Physiological studies of the stoneflies have shown that they can survive high temperatures (e.g., 25°C) for short time periods (Hotaling et al. 2020) and that their supercooling point is below 0°C (Hotaling et al. 2021). Another stonefly (Lednia tumana) that also lives in very cold water in the area was reared at five temperatures (1, 4, 7, 13 and 21°C) over a 31 day period. Results suggest that their ideal temperature lies between 1 and 13°C (Shah et al. 2023).

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Baumann R.W. and A.R. Gaufin .1971. New species of Nemoura from Western North America. Pan-Pacific Entomologist 47(4):27.

Baumann R.W. and A.R. Gaufin .1971. New species of Nemoura from Western North America. Pan-Pacific Entomologist 47(4):27. Baumann, R.W, A.R. Gaufin, and R.F. Surdick. 1977. The stoneflies (Plecoptera) of the Rocky Mountains. American Entomological Society, Philadelphia.

Baumann, R.W, A.R. Gaufin, and R.F. Surdick. 1977. The stoneflies (Plecoptera) of the Rocky Mountains. American Entomological Society, Philadelphia. Brighenti, S., S. Hotaling, D.S. Finn, A.G. Fountain, M. Hayashi, D. Herbst, J.E. Saros, L.M. Tronstad, C.I. Millar. 2021. Rock glaciers and related cold rocky landforms: overlooked climate refugia for mountain biodiversity. Global Change Biol. 27:1504-1517. DOI: 10.1111/gcb.15510

Brighenti, S., S. Hotaling, D.S. Finn, A.G. Fountain, M. Hayashi, D. Herbst, J.E. Saros, L.M. Tronstad, C.I. Millar. 2021. Rock glaciers and related cold rocky landforms: overlooked climate refugia for mountain biodiversity. Global Change Biol. 27:1504-1517. DOI: 10.1111/gcb.15510 Giersch, J.J., S. Hotaling, R.P. Kovach, L.A. Jones, and C.C. Muhlfeld. 2016. Climate-induced glacier and snow loss imperils alpine stream insects. Global Change Biology. 13 p. plus Supporting Information. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13565

Giersch, J.J., S. Hotaling, R.P. Kovach, L.A. Jones, and C.C. Muhlfeld. 2016. Climate-induced glacier and snow loss imperils alpine stream insects. Global Change Biology. 13 p. plus Supporting Information. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13565 Giersch, J.J., S. Jordan, G. Luikart, L.A. Jones, F.R. Hauer and C.C. Muhlfeld. 2015. Climate-induced range contraction of a rare alpine aquatic invertebrate. Freshwater Science. 34 (1):53-65.

Giersch, J.J., S. Jordan, G. Luikart, L.A. Jones, F.R. Hauer and C.C. Muhlfeld. 2015. Climate-induced range contraction of a rare alpine aquatic invertebrate. Freshwater Science. 34 (1):53-65. Hotaling, S., A.A. Shah, K.L. McGowan, L.M. Tronstad, J.J. Giersch, D.S. Finn, H.A. Woods, M.E. Dillon, J.L. Kelley. 2020. Mountain stoneflies may tolerate warming streams: evidence from organismal physiology and gene expression. Global Change Biology, 26:5524-5538.

Hotaling, S., A.A. Shah, K.L. McGowan, L.M. Tronstad, J.J. Giersch, D.S. Finn, H.A. Woods, M.E. Dillon, J.L. Kelley. 2020. Mountain stoneflies may tolerate warming streams: evidence from organismal physiology and gene expression. Global Change Biology, 26:5524-5538. Hotaling, S., A.A. Shah, M.E. Dillon, J.J. Giersch, L.M. Tronstad, D.S. Finn, H.A. Woods, and J.L. Kelley. 2021. Cold tolerance of mountain stoneflies (Plecoptera: Nemouridae) from the high Rocky Mountains. Western North American Naturalist 81(1):54-62.

Hotaling, S., A.A. Shah, M.E. Dillon, J.J. Giersch, L.M. Tronstad, D.S. Finn, H.A. Woods, and J.L. Kelley. 2021. Cold tolerance of mountain stoneflies (Plecoptera: Nemouridae) from the high Rocky Mountains. Western North American Naturalist 81(1):54-62. Hotaling, S., J.J. Giersch, D.S. Finn, L.M. Tronstad, S. Jordan, L.E. Serpa, R.G. Call, C.C. Muhlfeld, and D.W. Weisrock. 2019. Congruent population genetic structure but differing depths of divergence for three alpine stoneflies with similar ecology and geographic distributions. Freshwater Biology. 64:335-347

Hotaling, S., J.J. Giersch, D.S. Finn, L.M. Tronstad, S. Jordan, L.E. Serpa, R.G. Call, C.C. Muhlfeld, and D.W. Weisrock. 2019. Congruent population genetic structure but differing depths of divergence for three alpine stoneflies with similar ecology and geographic distributions. Freshwater Biology. 64:335-347 Jorgenson, K.L. 2022. Hydrologic source and trophic flexibility structure alpine stream food webs in the Teton Range, Wyoming. M.Sc. Thesis. Laramie, WY: University of Wyoming.

Jorgenson, K.L. 2022. Hydrologic source and trophic flexibility structure alpine stream food webs in the Teton Range, Wyoming. M.Sc. Thesis. Laramie, WY: University of Wyoming. Muhlfeld, C.C., T.J. Cline, J.J. Giersch, E. Peitzsch, C. Florentine, D. Jacobsen, and S. Hotaling. 2020. Specialized meltwater biodiversity persists despite widespread deglaciation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences May 2020, 202001697; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2001697117

Muhlfeld, C.C., T.J. Cline, J.J. Giersch, E. Peitzsch, C. Florentine, D. Jacobsen, and S. Hotaling. 2020. Specialized meltwater biodiversity persists despite widespread deglaciation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences May 2020, 202001697; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2001697117 Shah, A.A., S. Hotaling, A.B. Lapsansky, R.L. Malison, J.H. Birrell, T. Keeley, J.J. Giersch, L.M. Tronstad, H.A. Woods. 2023. Warming undermines emergence success in a threatened alpine stonefly: a multi-trait perspective on vulnerability to climate change. Functional Ecology 37:1033-1043. DOI: 10.1111/1365-2435.14284

Shah, A.A., S. Hotaling, A.B. Lapsansky, R.L. Malison, J.H. Birrell, T. Keeley, J.J. Giersch, L.M. Tronstad, H.A. Woods. 2023. Warming undermines emergence success in a threatened alpine stonefly: a multi-trait perspective on vulnerability to climate change. Functional Ecology 37:1033-1043. DOI: 10.1111/1365-2435.14284 Tronstad, L.M. Personal observation and unpublished data regarding Zapada glacier.

Tronstad, L.M. Personal observation and unpublished data regarding Zapada glacier. Tronstad, L.M., B. Tronstad, A. Lindsteadt, and S. Hotaling. 2022. Are western glacier stoneflies (Zapada glacier) more widely distributed in Wyoming alpine streams? Report prepared by the WY Natural Diversity Database, Univ. of WY for Region 2 USFS. 20 p.

Tronstad, L.M., B. Tronstad, A. Lindsteadt, and S. Hotaling. 2022. Are western glacier stoneflies (Zapada glacier) more widely distributed in Wyoming alpine streams? Report prepared by the WY Natural Diversity Database, Univ. of WY for Region 2 USFS. 20 p. Tronstad, L.M., S. Hotaling, J.J. Giersch, O.J. Wilmot, and D.S. Finn. 2020. Headwaters fed by subterranean ice: potential climate refugia for mountain stream communities? Western North American Naturalist 80(3):395-407.

Tronstad, L.M., S. Hotaling, J.J. Giersch, O.J. Wilmot, and D.S. Finn. 2020. Headwaters fed by subterranean ice: potential climate refugia for mountain stream communities? Western North American Naturalist 80(3):395-407.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Merritt, R.W. and K.W. Cummins. 1996. An introduction to the aquatic insects of North America. 3rd Edition. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. Dubuque, Iowa. 862 pp.

Merritt, R.W. and K.W. Cummins. 1996. An introduction to the aquatic insects of North America. 3rd Edition. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. Dubuque, Iowa. 862 pp. Newell, R.L. and R.W. Baumann. 2013. Studies on distribution and diversity of nearshore Ephemeroptera and Plecoptera in selected lakes of Glacier National Park, Montana. Western North American Naturalist 73(2): 230-236.

Newell, R.L. and R.W. Baumann. 2013. Studies on distribution and diversity of nearshore Ephemeroptera and Plecoptera in selected lakes of Glacier National Park, Montana. Western North American Naturalist 73(2): 230-236.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Western Glacier Stonefly"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Insects"