View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

Harlequin Duck - Histrionicus histrionicus

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Species is a summer breeding resident of swift-flowing streams and rivers across montane regions of western Montana. It has undergone declines over the past decades and the current trend of the population is unknown. It faces threats from increased flooding events during the nesting season and disturbance from recreational boating.

General Description

The Harlequin Duck is unique among North American waterfowl for breeding and foraging in clear, fast-flowing rivers and streams. The breeding plumage of adult males is unmistakable, with slate blue, white, black, and chestnut markings. This species is also unusual in its vocalizations; males and females give a mouselike squeak. The Harlequin Duck overwinters along coastal rocky shorelines (Robertson and Goudie 1999).

For a comprehensive review of the conservation status, habitat use, and ecology of this and other Montana bird species, please see

Marks et al. 2016, Birds of Montana.Phenology

In Montana, adults arrive from late April to early May (Kuchel 1977, Reichel and Genter 1996). Males depart breeding grounds in June while females and young depart from late July to early September (Kuchel 1977, Reichel and Genter 1994). Egg-laying occurs between April 30 and July 4 (Kuchel 1977, Reichel and Genter 1996). Kuchel (1977) estimated hatching dates for broods on McDonald Creek, Glacier National Park: 13 of 15 occurred between June 27 and July 7 with extremes on June 11 and August 2. Young fledge in Montana between July 15 and September 10, with most fledging between July 25 and August 15 (Kuchel 1977, Reichel and Genter 1996). Transients and winter observations recorded from October-March. Pairs observed beginning in April and May (Montana Natural Heritage Program Point Observation Database 2014).

Diagnostic Characteristics

The Harlequin Duck is a small diving duck. Male is larger than female. Breeding plumage of male is unmistakable: the body is slate blue with white bands and collars, bordered with black lines on chest and neck; large white crescent in front of eye with small white circular patch near ear; white vertical stripe on side of neck; black streak bordered by white and amber lines on top of head; iridescent blue secondaries; dark-slate-blue belly and chestnut-brown flanks. Adult female has brown body plumage, a white belly, with brown checks or spots, a round white spot behind ear, faded variable white patches in front of eye, and occasionally white streaks on back of head. Juveniles and immatures are similar to female, but feet are typically yellow, not gray (Robertson and Goudie 1999).

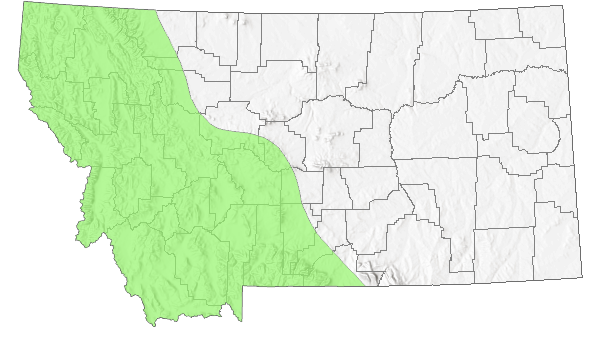

Species Range

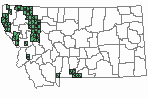

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

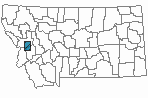

Western Hemisphere Range

Western Hemisphere Range

Range Comments

This species breeds in and along fast-moving, clear mountain streams, in western Montana. Regions with known breeding locations include the Absaroka/Beartooths, Middle and Lower Clark Fork, the Rocky Mountain Front, South Fork Flathead River, Glacier National Park, and the North Fork Flathead River. Observed in fall and winter in appropriate habitat (Montana Natural Heritage Program Point Observation Database 2014), but most individuals migrate to the west coast (Robertson and Goudie 1999).

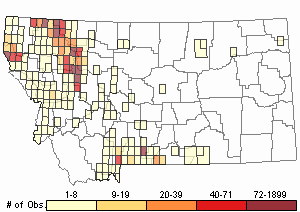

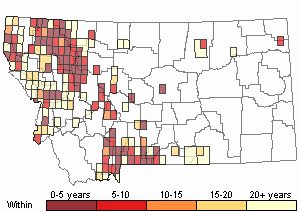

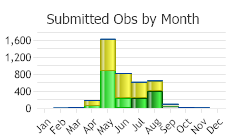

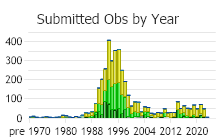

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 5481

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

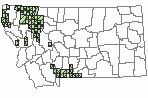

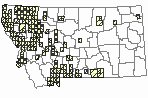

Relative Density

Recency

SUMMER (Feb 16 - Dec 14)

Direct Evidence of Breeding

Indirect Evidence of Breeding

No Evidence of Breeding

WINTER (Dec 15 - Feb 15)

Regularly Observed

Not Regularly Observed

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

Harlequin Ducks breeding in Montana arrive primarily from late April to early May (Kuchel 1977, Reichel and Genter 1996). Males depart in June while females and young depart from late July to early September (Kuchel 1977, Reichel and Genter 1994). Twenty-four birds banded in western Montana have been sighted off of Oregon (2), Washington (1) and southern British Columbia (21) (Ashley 1995, Reichel and Genter 1996).

Habitat

In Montana, Harlequin Ducks inhabit fast moving, low gradient, clear mountain streams. In Glacier National Park, birds used primarily old-growth or mature forest (90%); and 2) most birds in streams on the Rocky Mountain Front were observed in pole-sized timber (Diamond and Finnegan 1993). Banks are most often covered with a mosaic of trees and shrubs, but the only significant positive correlation is with overhanging vegetation (Diamond and Finnegan 1993, Ashley 1994).

The strongest stream section factor in Montana appears to be for stream reaches with at least two loafing sites per 10 meters (Kuchel 1977, Diamond and Finnegan 1993, Ashley 1994). Broods may preferentially use backwater areas, especially shortly after hatching (Kuchel 1977), though this is not apparent in data from other studies (Ashley 1994). Stream width ranges from 3 m to 35 m in Montana. Harlequin Ducks in Glacier National Park used straight, curved, meandering, and braided stream reaches in proportion to their availability (Ashley 1994).

National Vegetation Classification System Groups Associated with this Species

Wetland and Riparian

Riparian and Wetland Forest

Riparian Shrubland

Food Habits

Diet includes young and adult aquatic insects and fish roe. Birds dive to pick food from the surface of cobbles and gravel. This species will also pick food from the surface of the water (Robertson and Goudie 1999).

Ecology

In Montana, 53% of adult males returned to their breeding streams from the previous year, while females returned at a rate of 57% (Reichel and Genter 1996). Of 58 juveniles marked in 1992, at least 12 females and 2 males were alive in 1994 (Reichel and Genter 1996). All females known to be alive have returned to their natal streams, but no males have returned (Reichel and Genter 1996). Nearly all duckling (through fledging) mortality apparently occurs during the first 3 weeks following hatching (Kuchel 1977).

Densities of Harlequins in Montana range from 0.05 to 0.21 pairs per stream kilometer on the Rocky Mountain Front to 0.67 to 0.91 pairs per stream kilometer on McDonald Creek (Kuchel 1977). Linear home ranges averaged 7.7 km on McDonald Creek (Kuchel 1977). Four relatively long distance movements between streams, across large reservoirs or lakes, have been reported in Montana ranging from 16 to 31 km (Reichel and Genter 1996).

Reproductive Characteristics

Adults arrive as pairs on the breeding grounds. Female creates a nest scrape; nests are placed on the ground, in tree cavities, on stumps, and on small cliff ledges, generally within five meters of water. Clutch size averages five eggs. Male leaves the breeding grounds during incubation. Female incubates for approximately 28 days. Young are able to feed on their own within a day or two of hatching. Female typically remains with brood until migration (Robertson and Goudie 1999).

In Montana, no males have been reported on breeding streams prior to attaining adult plumage at 3-years of age (Phillips 1986, Reichel and Genter 1996). The youngest female known to have bred is a single 2-year-old (Reichel and Genter 1996).

In Montana during 1989 to 1994, annual numbers of ducklings fledged per adult female averaged 1.60 and ranged from 0.84 to 3.15 (n=230 adult females; Reichel and Genter 1995).

The proportion of females successfully raising a brood varies widely between years. In Montana, 230 females observed between 1989 and 1994 raised 103 broods for an average of 44.8% and ranged from 24% to 55% (Reichel and Genter 1995). High summer runoff has been associated with low productivity (Kuchel 1977, Diamond and Finnegan 1992, 1993, Reichel and Genter 1993, 1995).

Management

The Harlequin Duck is listed as a Sensitive Species by the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. In 2014, the first systematic statewide survey of known or likely brood streams for this species in Montana detected a total of 31 broods with 126 chicks. It is uncertain how these reproductive levels compare with previous surveys; however, Harlequin Duck reproduction was not detected in a large number of previously documented brood streams. Spring warming of 2014 occurred later than average and that, accompanied by a high snowpack, may have affected the suitability of some streams for breeding.

Stewardship Responsibility

Threats or Limiting Factors

Logging of mature forests likely has a detrimental impact to breeding habitat, not only influencing the availability of nest sites, but also impacting stream sedimentation, temperature, flow, and food availability. Additionally, mining activity and hydroelectric dams also pose a threat. This species is also sensitive to human disturbance, particularly if the disturbance is frequent and/or heavy (Robertson and Goudie 1999). Hunting has also been implicated in the decline of some populations.

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Ashley, J. 1994. 1992-93 harlequin duck monitoring and inventory in Glacier National Park, Montana. Unpublished report. Division of Research Management, Glacier Natl. Park, Montana. 57 pp.

Ashley, J. 1994. 1992-93 harlequin duck monitoring and inventory in Glacier National Park, Montana. Unpublished report. Division of Research Management, Glacier Natl. Park, Montana. 57 pp. Ashley, J. 1994. Progress report: harlequin duck inventory and monitoring in Glacier National Park, Montana. Unpublished report. Division of Research Management, Glacier Natl. Park, Montana. 14 pp.

Ashley, J. 1994. Progress report: harlequin duck inventory and monitoring in Glacier National Park, Montana. Unpublished report. Division of Research Management, Glacier Natl. Park, Montana. 14 pp. Ashley, J. 1995. Harlequin duck surveys and tracking in Glacier National Park, Montana. Unpublished report. Division of Natural Resources, Glacier National Park, West Glacier, Montana. 41 pp.

Ashley, J. 1995. Harlequin duck surveys and tracking in Glacier National Park, Montana. Unpublished report. Division of Natural Resources, Glacier National Park, West Glacier, Montana. 41 pp. Bent, A.C. 1925. Life histories of North American wild fowl. Order: Anseres (Part II). U.S. National Museum Bulletin 130. Washington, D.C. 316 pp.

Bent, A.C. 1925. Life histories of North American wild fowl. Order: Anseres (Part II). U.S. National Museum Bulletin 130. Washington, D.C. 316 pp. Diamond, S. and P. Finnegan. 1992. Harlequin duck ecology on Montana's Rocky Mountain Front. Unpublished report. Rocky Mountain District, Lewis & Clark National Forest, Choteau, MT. 45 pp.

Diamond, S. and P. Finnegan. 1992. Harlequin duck ecology on Montana's Rocky Mountain Front. Unpublished report. Rocky Mountain District, Lewis & Clark National Forest, Choteau, MT. 45 pp. Diamond, S. and P. Finnegan. 1993. Harlequin duck ecology on Montana's Rocky Mountain Front. Unpublished report. Rocky Mountain District, Lewis & Clark National Forest, Choteau, MT. 45 pp.

Diamond, S. and P. Finnegan. 1993. Harlequin duck ecology on Montana's Rocky Mountain Front. Unpublished report. Rocky Mountain District, Lewis & Clark National Forest, Choteau, MT. 45 pp. Fairman, L. and G. Miller. 1990. Results of the 1990 survey for harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Kootenai National Forest, Montana and parts of the Lolo National Forest, Montana. Helena, MT: Montana Natural Heritage Program. 43 p.

Fairman, L. and G. Miller. 1990. Results of the 1990 survey for harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Kootenai National Forest, Montana and parts of the Lolo National Forest, Montana. Helena, MT: Montana Natural Heritage Program. 43 p. Jewett, S. G. 1931. Nesting of the Pacific harlequin duck in Oregon. Condor 33:255.

Jewett, S. G. 1931. Nesting of the Pacific harlequin duck in Oregon. Condor 33:255. Kuchel, C. R. 1977. Some aspects of the behavior and ecology of Harlequin Ducks breeding in Glacier National Park, Montana. M.S. thesis. University of Montana, Missoula. 160 pp.

Kuchel, C. R. 1977. Some aspects of the behavior and ecology of Harlequin Ducks breeding in Glacier National Park, Montana. M.S. thesis. University of Montana, Missoula. 160 pp. Marks, J.S., P. Hendricks, and D. Casey. 2016. Birds of Montana. Arrington, VA. Buteo Books. 659 pages.

Marks, J.S., P. Hendricks, and D. Casey. 2016. Birds of Montana. Arrington, VA. Buteo Books. 659 pages. Phillips, J. C. 1986. A natural history of the ducks, vol. III. Dover Publications, Inc., NY. 383 pp.

Phillips, J. C. 1986. A natural history of the ducks, vol. III. Dover Publications, Inc., NY. 383 pp. Reichel, J.D. and D.L. Genter. 1993. Harlequin duck surveys in western Montana: 1992. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 67 pp., including appendices and maps.

Reichel, J.D. and D.L. Genter. 1993. Harlequin duck surveys in western Montana: 1992. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 67 pp., including appendices and maps. Reichel, J.D. and D.L. Genter. 1994. Harlequin duck surveys in western Montana: 1993. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 87 pp.

Reichel, J.D. and D.L. Genter. 1994. Harlequin duck surveys in western Montana: 1993. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 87 pp. Reichel, J.D. and D.L. Genter. 1995. Harlequin Duck surveys in western Montana: 1994. Montana Natural Heritage Program. 58 pp.

Reichel, J.D. and D.L. Genter. 1995. Harlequin Duck surveys in western Montana: 1994. Montana Natural Heritage Program. 58 pp. Reichel, J.D. and D.L. Genter. 1996. Harlequin duck surveys in western Montana: 1995. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. vii + 107 pp.

Reichel, J.D. and D.L. Genter. 1996. Harlequin duck surveys in western Montana: 1995. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. vii + 107 pp. Robertson, G. J., and R. I. Goudie. 1999. Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus). In The birds of North America, No. 466 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia and American Ornithologists’ Union.

Robertson, G. J., and R. I. Goudie. 1999. Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus). In The birds of North America, No. 466 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia and American Ornithologists’ Union.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? [WWPC] Washington Water Power Company. 1995. 1994 wildlife report Noxon Rapids and Cabinet Gorge Reservoirs. Washington Water Power Company. Spokane, WA.

[WWPC] Washington Water Power Company. 1995. 1994 wildlife report Noxon Rapids and Cabinet Gorge Reservoirs. Washington Water Power Company. Spokane, WA. American Ornithologists’ Union [AOU]. 1998. Check-list of North American birds, 7th edition. American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C. 829 p.

American Ornithologists’ Union [AOU]. 1998. Check-list of North American birds, 7th edition. American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C. 829 p. Ashley, J. 1994. Status of Harlequin ducks in Glacier National Park, Montana. P. 2 in: Proc. 2nd ann. Harlequin duck symposium, March 13-15, 1994. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 22 pp. plus appendices.

Ashley, J. 1994. Status of Harlequin ducks in Glacier National Park, Montana. P. 2 in: Proc. 2nd ann. Harlequin duck symposium, March 13-15, 1994. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 22 pp. plus appendices. Ashley, J. 1996. Harlequin duck inventory and monitoring in Glacier National Park, Montana. Unpublished report. Division of Natural Resources, Glacier National Park, West Glacier, Montana. 21 pp.

Ashley, J. 1996. Harlequin duck inventory and monitoring in Glacier National Park, Montana. Unpublished report. Division of Natural Resources, Glacier National Park, West Glacier, Montana. 21 pp. Ashley, J. 1997. Harlequin Duck inventory and monitoring in Glacier Natioanal Park, Montana. Unpublished (draft)report. Division of Natural Resources, Glacier National Park. West Glacier, Montana. 36 pp.

Ashley, J. 1997. Harlequin Duck inventory and monitoring in Glacier Natioanal Park, Montana. Unpublished (draft)report. Division of Natural Resources, Glacier National Park. West Glacier, Montana. 36 pp. Ashley, John. 1998. Harlequin Duck use on the Middle Fork of the Flathead River in the vicinity of the Essex bridge. MDOT Project BR 1-2(85)180/Control number 1763.

Ashley, John. 1998. Harlequin Duck use on the Middle Fork of the Flathead River in the vicinity of the Essex bridge. MDOT Project BR 1-2(85)180/Control number 1763. Atkinson, E. C. 1991. Distribution and status of harlequin ducks and common loons on the Targhee National Forest. Idaho Dep. of Fish and Game, Nongame and endangered wildlife prog. 27 pp.

Atkinson, E. C. 1991. Distribution and status of harlequin ducks and common loons on the Targhee National Forest. Idaho Dep. of Fish and Game, Nongame and endangered wildlife prog. 27 pp. Atkinson, E.C. 1991. Distribution and status of Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) and common loons (Gavia immer) on the Targhee National Forest. Cooperative Challenge Cost Share Project Report. Targhee National Forest and Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game. 43 p.

Atkinson, E.C. 1991. Distribution and status of Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) and common loons (Gavia immer) on the Targhee National Forest. Cooperative Challenge Cost Share Project Report. Targhee National Forest and Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game. 43 p. Atkinson, E.C. and M.L. Atkinson. 1990. Distribution and status of harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Targhee National Forest. Cooperative Challenge Cost Share Project. Boise, ID: Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game, Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Program. 25 p.

Atkinson, E.C. and M.L. Atkinson. 1990. Distribution and status of harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Targhee National Forest. Cooperative Challenge Cost Share Project. Boise, ID: Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game, Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Program. 25 p. Atkinson, E.G. 1991. Distribution of harlequin ducks ( Histrionicus histrionicus ) and common loons (Gavia immer) on the Targee National Forest. Coop. Challenge Cost Share Proj. Targee Natl. For. and Id. Dept. Fish Game.

Atkinson, E.G. 1991. Distribution of harlequin ducks ( Histrionicus histrionicus ) and common loons (Gavia immer) on the Targee National Forest. Coop. Challenge Cost Share Proj. Targee Natl. For. and Id. Dept. Fish Game. Bailey, V. and F.M. Bailey. 1918. Wild animals of Glacier National Park: the mammals, with notes on physiography and life zones, and the birds. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. 210 p.

Bailey, V. and F.M. Bailey. 1918. Wild animals of Glacier National Park: the mammals, with notes on physiography and life zones, and the birds. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. 210 p. Bate, L.J. 2010. Harlequin Duck surveys along upper McDonald Creek Glacier National Park. Division of Science and Resource Management Glacier National Park. 11pp.

Bate, L.J. 2010. Harlequin Duck surveys along upper McDonald Creek Glacier National Park. Division of Science and Resource Management Glacier National Park. 11pp. Bellrose, F.C. 1978. Harlequin duck. pp. 380-384. In: Ducks, geese, and swans of North America. Harrisburg, PA: Wildlife Management Institute, Stockpole Books. 540 p.

Bellrose, F.C. 1978. Harlequin duck. pp. 380-384. In: Ducks, geese, and swans of North America. Harrisburg, PA: Wildlife Management Institute, Stockpole Books. 540 p. Bengtson, S.A. 1972. Breeding ecology of the harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) in Iceland. Ornis Scandinavica 3:1-19.

Bengtson, S.A. 1972. Breeding ecology of the harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) in Iceland. Ornis Scandinavica 3:1-19. Bengtson, S.A. and S. Ulfstrand. 1971. Food resources and breeding frequency of the harlequin duck Histrionicus histrionicus in Iceland. Oikos 22:235-239.

Bengtson, S.A. and S. Ulfstrand. 1971. Food resources and breeding frequency of the harlequin duck Histrionicus histrionicus in Iceland. Oikos 22:235-239. Bengtson, S-A. 1966. Field studies on the harlequin duck in Iceland. Wildfowl Trust Ann. Rep. 17:79-84.

Bengtson, S-A. 1966. Field studies on the harlequin duck in Iceland. Wildfowl Trust Ann. Rep. 17:79-84. Bent, A. C. 1962. Life histories of North American wild fowl. Part II. New York, NY: Dover Publications. 865 p.

Bent, A. C. 1962. Life histories of North American wild fowl. Part II. New York, NY: Dover Publications. 865 p. Boyd, D. 1994. Conservation of harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus). Missoula, MT: University of Montana School of Forestry. 14 p.

Boyd, D. 1994. Conservation of harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus). Missoula, MT: University of Montana School of Forestry. 14 p. Breault, A. M. 1993. Harlequin duck status report 1992: British Columbia. Pp. 60-64 in: Cassirer, E. F., et al., (eds.), Status of Harlequin ducks in North America. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 83 pp.

Breault, A. M. 1993. Harlequin duck status report 1992: British Columbia. Pp. 60-64 in: Cassirer, E. F., et al., (eds.), Status of Harlequin ducks in North America. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 83 pp. Breault, A. M. and J.-P. L. Savard. 1991. Status report on the distribution and ecology of Harlequin Ducks in British Columbia. Can Wildlife Service, Pacific and Yukon Region, Tech. Rep. Series 110. 108 pp.

Breault, A. M. and J.-P. L. Savard. 1991. Status report on the distribution and ecology of Harlequin Ducks in British Columbia. Can Wildlife Service, Pacific and Yukon Region, Tech. Rep. Series 110. 108 pp. Brown, M. E. 1998. Population genetic structure, kinship, and social associations in three Harlequin Duck {Histrionicus histrionicus) breeding subpopulations. M.S. Thesis, University of California, Davis. 104 pp.

Brown, M. E. 1998. Population genetic structure, kinship, and social associations in three Harlequin Duck {Histrionicus histrionicus) breeding subpopulations. M.S. Thesis, University of California, Davis. 104 pp. Burleigh, T. D. 1952. Spring migration. Audubon Field Notes 6:258-260, 291, 292.

Burleigh, T. D. 1952. Spring migration. Audubon Field Notes 6:258-260, 291, 292. Burleigh, T.D. 1951. Spring migration. Audubon Field Notes 5:266-268.

Burleigh, T.D. 1951. Spring migration. Audubon Field Notes 5:266-268. Burleigh, T.D. 1972. Birds of Idaho. The Caxton Printers, Ltd., Caldwell, ID. 467 pp.

Burleigh, T.D. 1972. Birds of Idaho. The Caxton Printers, Ltd., Caldwell, ID. 467 pp. Byrd, G. V., J. C. Williams, and A. Durand. 1992. The status of Harlequin ducks in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska. Pp. 14-22 in: Proc. Harlequin Duck Symposium, April 23-24, 1992, Moscow, Idaho. ID Dept. of Fish & Game, U.S. For. Serv. Intermountain Research Station, ID Panhandle Nat. Forests, and Northwest Section of Wildlife Society. 46 pp.

Byrd, G. V., J. C. Williams, and A. Durand. 1992. The status of Harlequin ducks in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska. Pp. 14-22 in: Proc. Harlequin Duck Symposium, April 23-24, 1992, Moscow, Idaho. ID Dept. of Fish & Game, U.S. For. Serv. Intermountain Research Station, ID Panhandle Nat. Forests, and Northwest Section of Wildlife Society. 46 pp. Campbell, R.W., N.K. Dawe, I. McTaggart - Cowan, J.M. Cooper, G. Kaiser, and M.C.E. McNall. 1990. The birds of British Columbia. Vol. 1. Nonpasserines: introduction and loons through waterfowl. R. B.C. Mus., Victoria.

Campbell, R.W., N.K. Dawe, I. McTaggart - Cowan, J.M. Cooper, G. Kaiser, and M.C.E. McNall. 1990. The birds of British Columbia. Vol. 1. Nonpasserines: introduction and loons through waterfowl. R. B.C. Mus., Victoria. Carlson, J. C. 1990. Results of 1990 surveys for harlequin ducks on the Flathead National Forest, Montana. UnpubI. Rep., USDA Forest Service. 31 pp.

Carlson, J. C. 1990. Results of 1990 surveys for harlequin ducks on the Flathead National Forest, Montana. UnpubI. Rep., USDA Forest Service. 31 pp. Carlson, J.C. 1990. Results of harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) surveys in 1990 on the Flathead National Forest, Montana. Unpublished report to the USDA Forest Service, Cooperative Challenge Cost Share Program. 31 p.

Carlson, J.C. 1990. Results of harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) surveys in 1990 on the Flathead National Forest, Montana. Unpublished report to the USDA Forest Service, Cooperative Challenge Cost Share Program. 31 p. Casey, D. 2000. Partners in Flight Draft Bird Conservation Plan Montana. Version 1.0. 287 pp.

Casey, D. 2000. Partners in Flight Draft Bird Conservation Plan Montana. Version 1.0. 287 pp. Cassirer, E. F. 1993. Harlequin duck status report 1992: Idaho. pp. 27-30 In: Cassirer, E. F., et al., eds. Status of Harlequin ducks in North America. 83 pp.

Cassirer, E. F. 1993. Harlequin duck status report 1992: Idaho. pp. 27-30 In: Cassirer, E. F., et al., eds. Status of Harlequin ducks in North America. 83 pp. Cassirer, E. F. and C. R. Groves. 1994. Breeding ecology of Harlequin ducks in Idaho. P. 3 in: Proc. 2nd ann. Harlequin duck symposium, March 13-15, 1994. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 22 pp. plus appendices.

Cassirer, E. F. and C. R. Groves. 1994. Breeding ecology of Harlequin ducks in Idaho. P. 3 in: Proc. 2nd ann. Harlequin duck symposium, March 13-15, 1994. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 22 pp. plus appendices. Cassirer, E.F. 1989. Distribution and status of Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Nez Perce National Forest, Idaho. Report on Challenge Cost Share Project. 13 pp.

Cassirer, E.F. 1989. Distribution and status of Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Nez Perce National Forest, Idaho. Report on Challenge Cost Share Project. 13 pp. Cassirer, E.F. 1994. Proposed inventory and monitoring protocol for harlequin ducks in northern Idaho. Interagency Rare Animal Workshop. March 2, 1994. Post Falls, ID. 14 p.

Cassirer, E.F. 1994. Proposed inventory and monitoring protocol for harlequin ducks in northern Idaho. Interagency Rare Animal Workshop. March 2, 1994. Post Falls, ID. 14 p. Cassirer, E.F. 1995. Harlequin duck monitoring in northern Idaho, 1995. Cooperative project report. Idaho Department of Fish & Game, North Idaho Traditional Bowhunters, U.S. Forest Service, and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. 20 p.

Cassirer, E.F. 1995. Harlequin duck monitoring in northern Idaho, 1995. Cooperative project report. Idaho Department of Fish & Game, North Idaho Traditional Bowhunters, U.S. Forest Service, and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. 20 p. Cassirer, E.F. 1995. Harlequin duck monitoring on the Moyie River and other tributaries to the Kootenai River in northern Idaho subsequent to natural gas pipeline construction. [Unpublished report]. Lewiston, ID:Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 11 p.

Cassirer, E.F. 1995. Harlequin duck monitoring on the Moyie River and other tributaries to the Kootenai River in northern Idaho subsequent to natural gas pipeline construction. [Unpublished report]. Lewiston, ID:Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 11 p. Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1989. Breeding ecology of harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Kaniksu National Forest, Idaho. Report on Challenge Cost Share Project. 48 p.

Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1989. Breeding ecology of harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Kaniksu National Forest, Idaho. Report on Challenge Cost Share Project. 48 p. Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1990. A summary of harlequin duck sightings in Idaho, 1989. Boise, ID: Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game. 11 p.

Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1990. A summary of harlequin duck sightings in Idaho, 1989. Boise, ID: Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game. 11 p. Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1990. Distribution, habitat use and status of harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) in northern Idaho, 1990. Cooperative Challenge cost Share Project. Boise, ID: ID Dept. of Fish and Game, Nongame and Endangered Wildllife. 54 p.

Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1990. Distribution, habitat use and status of harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) in northern Idaho, 1990. Cooperative Challenge cost Share Project. Boise, ID: ID Dept. of Fish and Game, Nongame and Endangered Wildllife. 54 p. Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1990. Distribution, habitat use, and status of hariequin ducks in northern Idaho, 1990. Idaho Dept. Fish Game, Nongame Endangered Wildl. Prog. 54 pp.

Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1990. Distribution, habitat use, and status of hariequin ducks in northern Idaho, 1990. Idaho Dept. Fish Game, Nongame Endangered Wildl. Prog. 54 pp. Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1991. Harlequin duck ecology in Idaho: 1987-1990. Boise, ID: Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game. 93 p.

Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1991. Harlequin duck ecology in Idaho: 1987-1990. Boise, ID: Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game. 93 p. Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1992. Ecology of Harlequin Ducks in northern Idaho; progress report 1991. Boise, ID: Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game. 74 p.

Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1992. Ecology of Harlequin Ducks in northern Idaho; progress report 1991. Boise, ID: Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game. 74 p. Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1992. Status and Ecology of Harlequin Ducks in Idaho. In Proceedings, Harlequin Duck Symposium, April 23-24, 1992. Rep., 45pp. Idaho Dept. Fish and Game, Moscow, ID.

Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1992. Status and Ecology of Harlequin Ducks in Idaho. In Proceedings, Harlequin Duck Symposium, April 23-24, 1992. Rep., 45pp. Idaho Dept. Fish and Game, Moscow, ID. Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1994. Ecology of harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) in Northern Idaho. Study No. 4202-1-7-2. Boise, ID: Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 51 p.

Cassirer, E.F. and C.R. Groves. 1994. Ecology of harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) in Northern Idaho. Study No. 4202-1-7-2. Boise, ID: Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 51 p. Cassirer, E.F., C.R. Groves and R.L. Wallen. 1991. Distribution and population status of Harlequin Ducks in Idaho. Wilson Bull. 103(4): 723-725.

Cassirer, E.F., C.R. Groves and R.L. Wallen. 1991. Distribution and population status of Harlequin Ducks in Idaho. Wilson Bull. 103(4): 723-725. Cassirer, E.F., G. Schirato, F. Sharpe, C.R. Groves, and R.N. Anderson. 1993. Cavity nesting by Harlequin Ducks in the Pacific Northwest. Wilson Bulletin 105:691-694.

Cassirer, E.F., G. Schirato, F. Sharpe, C.R. Groves, and R.N. Anderson. 1993. Cavity nesting by Harlequin Ducks in the Pacific Northwest. Wilson Bulletin 105:691-694. Cassirer, E.F., J.D. Reichel, R.L. Wallen, and E. Atkinson. 1996. Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) habitat conservation assessment and strategy for the U.S. Rocky Mountains. USFS BLM. 54 p.

Cassirer, E.F., J.D. Reichel, R.L. Wallen, and E. Atkinson. 1996. Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) habitat conservation assessment and strategy for the U.S. Rocky Mountains. USFS BLM. 54 p. Cassirer, F. 1995. Harlequin duck monitoring in northern Idaho, 1995. Cooperative project report. Idaho Dept. of Fish & Game, North Idaho Traditional Bowhunters, U.S. Forest Service, and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. 20 pp.

Cassirer, F. 1995. Harlequin duck monitoring in northern Idaho, 1995. Cooperative project report. Idaho Dept. of Fish & Game, North Idaho Traditional Bowhunters, U.S. Forest Service, and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. 20 pp. Castren. Chad. 1992. [Report on field surveys for harlequin ducks, summer 1992].

Castren. Chad. 1992. [Report on field surveys for harlequin ducks, summer 1992]. Center. D. L. 1992. [Field notes from 13 August re: banding harlequin ducks on Spotted Bear River.]

Center. D. L. 1992. [Field notes from 13 August re: banding harlequin ducks on Spotted Bear River.] Chadwick, D. H. 1992. Some observations of a concentration of harlequin ducks in the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia. Pp. 33-40 in: Proceedings Harlequin Duck Symposium, Apr 23-24, 1992, Moscow, ID. 45 pp.

Chadwick, D. H. 1992. Some observations of a concentration of harlequin ducks in the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia. Pp. 33-40 in: Proceedings Harlequin Duck Symposium, Apr 23-24, 1992, Moscow, ID. 45 pp. Chadwick, D.H. 1993. Bird of white waters. National Geographic 184(5):116-132.

Chadwick, D.H. 1993. Bird of white waters. National Geographic 184(5):116-132. Chadwick, D.H. No Date. Look at the Harlequins! Whitefish. pp. 27-29, 80-81.

Chadwick, D.H. No Date. Look at the Harlequins! Whitefish. pp. 27-29, 80-81. Clarkson, P. 1992. A preliminary investigation into the status and distribution of harlequin ducks in Jasper National Park. Unpublished Technical Report. Natural Resource Conservation, Jasper National Park, Alberta. 63pp.

Clarkson, P. 1992. A preliminary investigation into the status and distribution of harlequin ducks in Jasper National Park. Unpublished Technical Report. Natural Resource Conservation, Jasper National Park, Alberta. 63pp. Clarkson, P. 1994. Managing watersheds for harlequin ducks. Unpublished presentation. American River Management Society River Without Boundaries Symposium, Grand Junction, CO. 33 pp.

Clarkson, P. 1994. Managing watersheds for harlequin ducks. Unpublished presentation. American River Management Society River Without Boundaries Symposium, Grand Junction, CO. 33 pp. Clarkson, P. and R. I. Goudie. 1994. Capture techniques and 1993 banding results for moulting Harlequin ducks in the Strait of Georgia, B.C. Pp. 11-14 in: Proc. 2nd ann. Harlequin duck symposium, March 13-15, 1994. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 22 pp. plus appendices.

Clarkson, P. and R. I. Goudie. 1994. Capture techniques and 1993 banding results for moulting Harlequin ducks in the Strait of Georgia, B.C. Pp. 11-14 in: Proc. 2nd ann. Harlequin duck symposium, March 13-15, 1994. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 22 pp. plus appendices. Cooke, F. G. J. Robertson, C. M. Smith, R. I. Goudie, and W. S. Boyd. 2000. Survival, emigration, and winter population structure of Harlequin Ducks. Condor 102:137-144.

Cooke, F. G. J. Robertson, C. M. Smith, R. I. Goudie, and W. S. Boyd. 2000. Survival, emigration, and winter population structure of Harlequin Ducks. Condor 102:137-144. Cooke, F., G. J. Robertson, R. I. Goudie and W. S. Boyd. 1997. Molt and the basic plumage of male Harlequin Ducks. Condor 99:83-90.

Cooke, F., G. J. Robertson, R. I. Goudie and W. S. Boyd. 1997. Molt and the basic plumage of male Harlequin Ducks. Condor 99:83-90. Cottam, Clarence. 1939. Food habits of North American diving ducks. USDA Tech. Bull. No. 643:81-86.

Cottam, Clarence. 1939. Food habits of North American diving ducks. USDA Tech. Bull. No. 643:81-86. Coudie. R. I. 1984. Comparative ecology of Common eiders, black scoters, oldsquaws and harlequin ducks wintering in southeast Newfoundland. Thesis. Univ. of W. Ontario. London, Ontario. Canada.

Coudie. R. I. 1984. Comparative ecology of Common eiders, black scoters, oldsquaws and harlequin ducks wintering in southeast Newfoundland. Thesis. Univ. of W. Ontario. London, Ontario. Canada. Crowley, D. W. 1994. Breeding habitat of Harlequin ducks in Prince William Sound, Alaska. P. 4 in: Proc. 2nd ann. Harlequin duck symposium, March 13-15, 1994. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 22 pp. plus appendices.

Crowley, D. W. 1994. Breeding habitat of Harlequin ducks in Prince William Sound, Alaska. P. 4 in: Proc. 2nd ann. Harlequin duck symposium, March 13-15, 1994. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 22 pp. plus appendices. Davis, C.V. 1961. A distributional study of the birds of Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University. 462 p.

Davis, C.V. 1961. A distributional study of the birds of Montana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University. 462 p. Devlin, S. Wildlife biologists can't get enough of the elusive harlequin duck. Missoula, MT: Missoulian. 23 May 1991. p. 1C.

Devlin, S. Wildlife biologists can't get enough of the elusive harlequin duck. Missoula, MT: Missoulian. 23 May 1991. p. 1C. Diamond. Seth. 1990. [Various reports of harlequin sightings along the RMF during 1990.]

Diamond. Seth. 1990. [Various reports of harlequin sightings along the RMF during 1990.] Dzinbal, K. A. 1982. Ecology of Harlequin ducks in Prince William Sound, Alaska, during summer. M.S. thesis. Ore. State Univ., Corvallis. 89 pp.

Dzinbal, K. A. 1982. Ecology of Harlequin ducks in Prince William Sound, Alaska, during summer. M.S. thesis. Ore. State Univ., Corvallis. 89 pp. Dzinbal, K.A. and R.L. Jarvis. 1982. Coastal feeding ecology of harlequin ducks in Prince William Sound, Alaska, during summer. pp. 6-8. In: D.N. Nettleship, et al. (eds). Marine birds: their feeding ecology and commercial fisheries relationships. Seattle, WA: Canadian Wildlife Service Special Publication from Proc. Pacific Seabird Group Symposium, January 6-8.

Dzinbal, K.A. and R.L. Jarvis. 1982. Coastal feeding ecology of harlequin ducks in Prince William Sound, Alaska, during summer. pp. 6-8. In: D.N. Nettleship, et al. (eds). Marine birds: their feeding ecology and commercial fisheries relationships. Seattle, WA: Canadian Wildlife Service Special Publication from Proc. Pacific Seabird Group Symposium, January 6-8. Ehrlich, P., D. Dobkin, and D. Wheye. 1988. The birder’s handbook: a field guide to the natural history of North American birds. Simon and Schuster Inc. New York. 785 pp.

Ehrlich, P., D. Dobkin, and D. Wheye. 1988. The birder’s handbook: a field guide to the natural history of North American birds. Simon and Schuster Inc. New York. 785 pp. Fairman, L.M., C. Jones, and D.L. Genter. 1989. Results of the 1989 survey for Harlequin Ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Kootenai National Forest, Montana and Flathead National Forest, Montana. Mont. Nat. Heritage Prog., Helena. 20 p.

Fairman, L.M., C. Jones, and D.L. Genter. 1989. Results of the 1989 survey for Harlequin Ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Kootenai National Forest, Montana and Flathead National Forest, Montana. Mont. Nat. Heritage Prog., Helena. 20 p. Fairman, L.M., D.L. Genter, and C. Jones. 1990. An overview of the ecology of the boreal owl (Aegolius funereus). Unpublished report. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 32 pp.

Fairman, L.M., D.L. Genter, and C. Jones. 1990. An overview of the ecology of the boreal owl (Aegolius funereus). Unpublished report. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 32 pp. Fleischner, T L. 1983. Natural history of Harlequin ducks wintering in northern Puget Sound. M.Sc. Thesis. Bellingham, WA: Western Washington University. 49 p.

Fleischner, T L. 1983. Natural history of Harlequin ducks wintering in northern Puget Sound. M.Sc. Thesis. Bellingham, WA: Western Washington University. 49 p. Flint, V. E., R. L. Boehme, Y. V. Kostin, and A. A. Kuznetsov, (eds.). 1984. Harlequin duck. p. 50 In: Birds of the USSR. Norwalk, CT: The Easton Press. 353 p.

Flint, V. E., R. L. Boehme, Y. V. Kostin, and A. A. Kuznetsov, (eds.). 1984. Harlequin duck. p. 50 In: Birds of the USSR. Norwalk, CT: The Easton Press. 353 p. Fournier, M. A., and R. G. Bromley. 1996. Status of the Harlequin Duck, Histrionicus histrionicus, in the western Northwest Territories. Canadian Field-Nat. 110:638-641.

Fournier, M. A., and R. G. Bromley. 1996. Status of the Harlequin Duck, Histrionicus histrionicus, in the western Northwest Territories. Canadian Field-Nat. 110:638-641. Gaines, W.L. and R.E. Fitzner. 1987. Winter diet of Harlequin duck at Sequim Bay, Puget Sound, Washington. Northwest Science 61(4):213-215.

Gaines, W.L. and R.E. Fitzner. 1987. Winter diet of Harlequin duck at Sequim Bay, Puget Sound, Washington. Northwest Science 61(4):213-215. Gangemi, J.T. 1991. Results of the 1991 survey for Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus); distribution in the non-wilderness portion of the Flathead National Forest, Montana. Unpublished report for the MTNHP. 26 pp.

Gangemi, J.T. 1991. Results of the 1991 survey for Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus); distribution in the non-wilderness portion of the Flathead National Forest, Montana. Unpublished report for the MTNHP. 26 pp. Genter, D. L. 1992. Status of the Harlequin duck in Montana. P. 5 in: Proc. Harlequin duck symp., April 23-24, 1992, Moscow, Idaho. ID Dept. of Fish & Game, U.S. For. Serv. Intermtn. Res. Stat., ID Panhandle Nat. Forests, and NW Sect. of Wildl. Soc. 46 pp.

Genter, D. L. 1992. Status of the Harlequin duck in Montana. P. 5 in: Proc. Harlequin duck symp., April 23-24, 1992, Moscow, Idaho. ID Dept. of Fish & Game, U.S. For. Serv. Intermtn. Res. Stat., ID Panhandle Nat. Forests, and NW Sect. of Wildl. Soc. 46 pp. Genter, D. L. 1993. Harlequin duck status report 1992: Montana. Pp. 31-34 in: Cassirer, E. F., et al., (eds.), Status of harlequin ducks in North America. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 83 p.

Genter, D. L. 1993. Harlequin duck status report 1992: Montana. Pp. 31-34 in: Cassirer, E. F., et al., (eds.), Status of harlequin ducks in North America. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 83 p. Genter, D.L. 1993. Whitewater wonder. Montana Outdoors, July/August 24(4):2-7.

Genter, D.L. 1993. Whitewater wonder. Montana Outdoors, July/August 24(4):2-7. Genter, D.L. 1994. Variation in productivity of Harlequin Ducks breeding in Montana. P. 19 in: Proc. 2nd ann. Harlequin duck symposium, March 13-15, 1994. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 22 pp. plus appendices.

Genter, D.L. 1994. Variation in productivity of Harlequin Ducks breeding in Montana. P. 19 in: Proc. 2nd ann. Harlequin duck symposium, March 13-15, 1994. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 22 pp. plus appendices. Goudie, R. I. 1988. Breeding distribution of harlequin ducks in northern Labrador. Atlantic Soc. of Fish and Wildl. Biologists. 4(2):17-21.

Goudie, R. I. 1988. Breeding distribution of harlequin ducks in northern Labrador. Atlantic Soc. of Fish and Wildl. Biologists. 4(2):17-21. Goudie, R.I. 1989. Historical status of harlequin ducks wintering in eastern North America: a reappraisal. Wilson Bulletin 101(1):112-114.

Goudie, R.I. 1989. Historical status of harlequin ducks wintering in eastern North America: a reappraisal. Wilson Bulletin 101(1):112-114. Goudie, R.I. 1991. The status of the Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) in eastern North America. Committee on the status of endangered wildlife in Canada (Cosewic), Ottawa, Ontario. 59 pp. + 4 appendices.

Goudie, R.I. 1991. The status of the Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) in eastern North America. Committee on the status of endangered wildlife in Canada (Cosewic), Ottawa, Ontario. 59 pp. + 4 appendices. Groves, C., Wallen, W. and F. Cassirer. 1990. Clown on the water. Idaho Wildlife 10(3):24-25.

Groves, C., Wallen, W. and F. Cassirer. 1990. Clown on the water. Idaho Wildlife 10(3):24-25. Gudmundsson, F. 1971. Straumendur (Histrionicus histrionicus) a Islande. ('The harlequin duck in Iceland') Natturufroedingurinn 41(1):1-28, (2)64-98. (English summary pp. 84-98).

Gudmundsson, F. 1971. Straumendur (Histrionicus histrionicus) a Islande. ('The harlequin duck in Iceland') Natturufroedingurinn 41(1):1-28, (2)64-98. (English summary pp. 84-98). Hand, R.L. 1969. A distributional checklist of the birds of western Montana. Unpublished. Available at Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula.

Hand, R.L. 1969. A distributional checklist of the birds of western Montana. Unpublished. Available at Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula. Hansen, Warren. 2014. Causes of annual reproductive variation and anthropogenic disturbance in Harlequin Ducks breeding in Glacier National Park, Montana. MS Thesis. University of Montana.

Hansen, Warren. 2014. Causes of annual reproductive variation and anthropogenic disturbance in Harlequin Ducks breeding in Glacier National Park, Montana. MS Thesis. University of Montana. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 1993. Status of harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) in North America. iii + 83 pp.

Harlequin Duck Working Group. 1993. Status of harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) in North America. iii + 83 pp. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 1994. Proceedings of the second Harlequin duck symposium. March 13-15. Hornby Island, British Columbia. 22 p.

Harlequin Duck Working Group. 1994. Proceedings of the second Harlequin duck symposium. March 13-15. Hornby Island, British Columbia. 22 p. Hays, R., R.L. Eng, and C.V. Davis (preparers). 1984. A list of Montana birds. Helena, MT: MT Dept. of Fish, Wildlife & Parks.

Hays, R., R.L. Eng, and C.V. Davis (preparers). 1984. A list of Montana birds. Helena, MT: MT Dept. of Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Hendricks, P. 1999. Harlequin duck research and monitoring in Montana: 1998. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT 30pp.

Hendricks, P. 1999. Harlequin duck research and monitoring in Montana: 1998. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT 30pp. Hendricks, P. 2000. Harlequin Duck research and monitoring in Montana: 1999. Unpublished report, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 34 pp.

Hendricks, P. 2000. Harlequin Duck research and monitoring in Montana: 1999. Unpublished report, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 34 pp. Hendricks, P. 2005. Surveys for animal species of concern in northwestern Montana. Unpublished report to the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana, May 2005. 53 p.

Hendricks, P. 2005. Surveys for animal species of concern in northwestern Montana. Unpublished report to the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana, May 2005. 53 p. Hendricks, P. And J.D. Reichel. 1998. Harlequin Duck Research and Monitoring in Montana: 1997. Unpublished Report to ASARCO, Incorporated. 28 p.

Hendricks, P. And J.D. Reichel. 1998. Harlequin Duck Research and Monitoring in Montana: 1997. Unpublished Report to ASARCO, Incorporated. 28 p. Hendricks, P., S. Lenard, and C. Currier. 2004. Harlequin Duck Surveys, McDonald Creek Area, Glacier National Park, 2004. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 11 p.

Hendricks, P., S. Lenard, and C. Currier. 2004. Harlequin Duck Surveys, McDonald Creek Area, Glacier National Park, 2004. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 11 p. Holmes, H.A. 2025. Investigating non-invasive survey methods and building a predictive occupancy model for harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) in western Montana and northern Idaho. Masters of Science in Wildlife Biology. University of Montana. 86 p.

Holmes, H.A. 2025. Investigating non-invasive survey methods and building a predictive occupancy model for harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) in western Montana and northern Idaho. Masters of Science in Wildlife Biology. University of Montana. 86 p. Hunt, W. A. 1993. Jasper National Park harlequin duck projects, 1992: Maligne Valley pilot projects. Canadian Parks Service, Jasper National Park. 58 pp.

Hunt, W. A. 1993. Jasper National Park harlequin duck projects, 1992: Maligne Valley pilot projects. Canadian Parks Service, Jasper National Park. 58 pp. Hunt, W. A. 1993. Jasper National Park harlequin duck research project, 1992 pilot projects--interim results. Jasper Warden Service Biological Report Series, No. 1. Heritage Resource Conservation, Parks Canada, Box 10, Jasper, Alberta. 67 pp.

Hunt, W. A. 1993. Jasper National Park harlequin duck research project, 1992 pilot projects--interim results. Jasper Warden Service Biological Report Series, No. 1. Heritage Resource Conservation, Parks Canada, Box 10, Jasper, Alberta. 67 pp. Inglis, I.R., J. Lazarus, and R. Torrance. 1989. The pre-nesting behavior and time budget of the Harlequin duck Histrionicus histrionicus. Wildfowl 40:55-73.

Inglis, I.R., J. Lazarus, and R. Torrance. 1989. The pre-nesting behavior and time budget of the Harlequin duck Histrionicus histrionicus. Wildfowl 40:55-73. Johnsgard, P.A. 1975. Waterfowl of North America. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. 575 p.

Johnsgard, P.A. 1975. Waterfowl of North America. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. 575 p. Johnsgard, P.A. 1992. Birds of the Rocky Mountains with particular reference to national parks in the northern Rocky Mountain region. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. xi + 504 pp.

Johnsgard, P.A. 1992. Birds of the Rocky Mountains with particular reference to national parks in the northern Rocky Mountain region. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. xi + 504 pp. Johnson, D. 1991. Field report of harlequin duck streams surveyed. Unpubl. field notes on file Mont. Nat. Heritage Prog., Helena, Mont.

Johnson, D. 1991. Field report of harlequin duck streams surveyed. Unpubl. field notes on file Mont. Nat. Heritage Prog., Helena, Mont. Johnson, D.D. 1991. Productivity and the importance of vegetation: the link between harlequin duck winter and summer habitat. Unpublished Report. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 14 p.

Johnson, D.D. 1991. Productivity and the importance of vegetation: the link between harlequin duck winter and summer habitat. Unpublished Report. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 14 p. Johnson, D.D. 1991. Results of stream surveys for Harlequin ducks in the Gallatin and a section of the Custer National Forests, Montana. Unpublished report to the Montana Natural Heritage Program. 18 pp.

Johnson, D.D. 1991. Results of stream surveys for Harlequin ducks in the Gallatin and a section of the Custer National Forests, Montana. Unpublished report to the Montana Natural Heritage Program. 18 pp. Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. Kerr, R. 1989. Field survey summary report of the Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Kootenai National Forest, Montana. 16 pp.

Kerr, R. 1989. Field survey summary report of the Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Kootenai National Forest, Montana. 16 pp. Laurion, T. and B. Oakleaf. 1995. Harlequin duck survey, Shoshone National Forest. Wyoming Game and Fish Dept., Laramie, WY. 10pp.

Laurion, T. and B. Oakleaf. 1995. Harlequin duck survey, Shoshone National Forest. Wyoming Game and Fish Dept., Laramie, WY. 10pp. Lee, D.N.B., and D.L. Genter. 1991. Results of harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) surveys in wilderness areas of the Flathead National Forest, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 31 pp.

Lee, D.N.B., and D.L. Genter. 1991. Results of harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) surveys in wilderness areas of the Flathead National Forest, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 31 pp. Lenard, S., J. Carlson, J. Ellis, C. Jones, and C. Tilly. 2003. P. D. Skaar's Montana bird distribution, 6th edition. Montana Audubon, Helena, MT. 144 pp.

Lenard, S., J. Carlson, J. Ellis, C. Jones, and C. Tilly. 2003. P. D. Skaar's Montana bird distribution, 6th edition. Montana Audubon, Helena, MT. 144 pp. Lindler, B. The shy harlequin duck flutters its feathers in Montana. Great Falls, MT. Great Falls Tribune. 8 November 1990. p. 1D.

Lindler, B. The shy harlequin duck flutters its feathers in Montana. Great Falls, MT. Great Falls Tribune. 8 November 1990. p. 1D. Loftus, B. Romance of the harlequin. Lewiston, MT: Lewiston Tribune. 29 June 1989. pp. 1B, 6B.

Loftus, B. Romance of the harlequin. Lewiston, MT: Lewiston Tribune. 29 June 1989. pp. 1B, 6B. Machmer, M.M. 2001. Salmo River Harlequin duck inventory, monitoring and brood habitat assessment. Prepared for Columbia Basin Fish & Wildlife Compensation Program by Pandion Ecological Research. 48 p.

Machmer, M.M. 2001. Salmo River Harlequin duck inventory, monitoring and brood habitat assessment. Prepared for Columbia Basin Fish & Wildlife Compensation Program by Pandion Ecological Research. 48 p. Maj, M. E. And M. B. Whitfield. 1995. Harlequin duck surveys, final report 1995, Targhee National Forest. U.S. Forest Serv., Targhee Nat. For, Idaho Dep. Fish and Game, Northern Rockies Cons. Coop. 21 pp.

Maj, M. E. And M. B. Whitfield. 1995. Harlequin duck surveys, final report 1995, Targhee National Forest. U.S. Forest Serv., Targhee Nat. For, Idaho Dep. Fish and Game, Northern Rockies Cons. Coop. 21 pp. Markum, D. 1990. Distribution and status of the Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Gallatin National Forest, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 54pp

Markum, D. 1990. Distribution and status of the Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) on the Gallatin National Forest, Montana. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 54pp Markum, D. 1990. Preliminary report on the distribution and status of the harlequin duck, Histrionicus histrionicus on the Gallatin National Forest, Montana. Unpublished report for the Gallatin National Forest. Montana National Heritage Program. 21 pp.

Markum, D. 1990. Preliminary report on the distribution and status of the harlequin duck, Histrionicus histrionicus on the Gallatin National Forest, Montana. Unpublished report for the Gallatin National Forest. Montana National Heritage Program. 21 pp. McEneaney, T. 1997. Harlequins: noble ducks of turbulent waters. Yellowstone Science 5(Spring):2-7.

McEneaney, T. 1997. Harlequins: noble ducks of turbulent waters. Yellowstone Science 5(Spring):2-7. Merriam, C.H. 1883. Breeding of the harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) in Newfoundland. Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club 8:200.

Merriam, C.H. 1883. Breeding of the harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) in Newfoundland. Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club 8:200. Michael, C. W. and E. Michael. 1922. An adventure with a pair of harlequin ducks in the Yosemite Valley. Auk 39:14-23.

Michael, C. W. and E. Michael. 1922. An adventure with a pair of harlequin ducks in the Yosemite Valley. Auk 39:14-23. Miller, V.E. 1988. Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) 1988 results of field survey in west-central Montana. Prepared for Professor James Lowe, Forestry 220. 18 pp.

Miller, V.E. 1988. Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) 1988 results of field survey in west-central Montana. Prepared for Professor James Lowe, Forestry 220. 18 pp. Miller, V.E. 1988. Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) 1988 results of field surveys in west-central Montana. Unpublished report to the Montana Natural Heritage Program.

Miller, V.E. 1988. Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) 1988 results of field surveys in west-central Montana. Unpublished report to the Montana Natural Heritage Program. Miller, V.E. 1989. 1989 field survey report: harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus). Lower Clark Fork River drainage, west-central, Montana. Unpubl. rep. on file Mont. Nat. Heritage Prog., Helena. 48+ pp.

Miller, V.E. 1989. 1989 field survey report: harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus). Lower Clark Fork River drainage, west-central, Montana. Unpubl. rep. on file Mont. Nat. Heritage Prog., Helena. 48+ pp. Miller, V.E. 1989. Field Survey Report, Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus): Lower Clark Fork Drainage, West Central Montana. Unpublished, 47 pp.

Miller, V.E. 1989. Field Survey Report, Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus): Lower Clark Fork Drainage, West Central Montana. Unpublished, 47 pp. Mittelhauser, G. 1991. Harlequin ducks at Acadia National Park and coastal Maine, 1988-1991. Island Research Center, College of the Atlantic, Bar Harbor, Maine. 67 pp.

Mittelhauser, G. 1991. Harlequin ducks at Acadia National Park and coastal Maine, 1988-1991. Island Research Center, College of the Atlantic, Bar Harbor, Maine. 67 pp. Mittelhauser, G. H. 1990. Survey of harlequin ducks along the Isla au Haut shoreline and adjacent offshore islands, 1989-90. Unpublished report, College of the Atlantic, Bar Harbor, Maine. 25 pp.

Mittelhauser, G. H. 1990. Survey of harlequin ducks along the Isla au Haut shoreline and adjacent offshore islands, 1989-90. Unpublished report, College of the Atlantic, Bar Harbor, Maine. 25 pp. Mittelhauser, G.H. 1989. The ecology and distribution of the harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) wintering off Isle au Haut, Maine. B.A. thesis. College of the Atlantic. 69 pp.

Mittelhauser, G.H. 1989. The ecology and distribution of the harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) wintering off Isle au Haut, Maine. B.A. thesis. College of the Atlantic. 69 pp. Montana Bird Distribution Committee. 1996. P. D. Skaar's Montana Bird Distribution, Fifth Edition. Special Publication No. 3. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 130 pp.

Montana Bird Distribution Committee. 1996. P. D. Skaar's Montana Bird Distribution, Fifth Edition. Special Publication No. 3. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 130 pp. Montana Bird Distribution Committee. 2012. P.D. Skaar's Montana bird distribution. 7th Edition. Montana Audubon, Helena, Montana. 208 pp. + foldout map.

Montana Bird Distribution Committee. 2012. P.D. Skaar's Montana bird distribution. 7th Edition. Montana Audubon, Helena, Montana. 208 pp. + foldout map. Montana Department of Natural Resource Conservation. 1982. Kootenai Falls wildlife monitoring study, third annual report for the period September 2, 1981 - September 1, 1982. 36 pp.

Montana Department of Natural Resource Conservation. 1982. Kootenai Falls wildlife monitoring study, third annual report for the period September 2, 1981 - September 1, 1982. 36 pp. Montevecchi, W. A., A. Bourget, J. Brazil, R. I. Goudie, A. E. Hutchinson, B. C. Johnson, P. Kehoe, P. Laporte, M. A. McCollough, R. Milton, and N. Seymour. 1995. National recovery plan for the Harlequin Duck in eastern North America. Prepared by the Harlequin Duck (eastern North Am. pop.) Recovery Team for the Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife Committee. 31 pp.

Montevecchi, W. A., A. Bourget, J. Brazil, R. I. Goudie, A. E. Hutchinson, B. C. Johnson, P. Kehoe, P. Laporte, M. A. McCollough, R. Milton, and N. Seymour. 1995. National recovery plan for the Harlequin Duck in eastern North America. Prepared by the Harlequin Duck (eastern North Am. pop.) Recovery Team for the Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife Committee. 31 pp. Morneau, F. and R. Decarie. 1994. Status and distribution of Harlequin ducks in the Great Whale Watershed, Quebec. Pp. 6-7 in: Proc. 2nd ann. Harlequin duck symposium, March 13-15, 1994. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 22 pp. plus appendices.

Morneau, F. and R. Decarie. 1994. Status and distribution of Harlequin ducks in the Great Whale Watershed, Quebec. Pp. 6-7 in: Proc. 2nd ann. Harlequin duck symposium, March 13-15, 1994. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 22 pp. plus appendices. Multiple Authors. 1992. Abstracts from Montana Rare Animal Meeting. Lewistown, MT. November 5-6, 1992. 20 p.

Multiple Authors. 1992. Abstracts from Montana Rare Animal Meeting. Lewistown, MT. November 5-6, 1992. 20 p. Nichols, P. A., L. S. Thompson, and J. Elliot. 1982. Kootenai River Hydroelectric Project, terrestrial life and habitats. Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation, Helena, MT. 176 pp. plus figures.

Nichols, P. A., L. S. Thompson, and J. Elliot. 1982. Kootenai River Hydroelectric Project, terrestrial life and habitats. Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation, Helena, MT. 176 pp. plus figures. Oechsli, L.M. 2000. Ex-urban development in the Rocky Mountain West: consequences for native vegetation, wildlife diversity, and land-use planning in Big Sky, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 73 p.

Oechsli, L.M. 2000. Ex-urban development in the Rocky Mountain West: consequences for native vegetation, wildlife diversity, and land-use planning in Big Sky, Montana. M.Sc. Thesis. Montana State University, Bozeman. 73 p. Palmer, R.S. 1962. Handbook of North American birds. Volume 1. Loons through flamingos. Yale University Press, New Haven. 567 pp.

Palmer, R.S. 1962. Handbook of North American birds. Volume 1. Loons through flamingos. Yale University Press, New Haven. 567 pp. Patten, S. 1993. Reproductive failure of harlequin ducks. Alaska's Wildlife, January/February:14-15.

Patten, S. 1993. Reproductive failure of harlequin ducks. Alaska's Wildlife, January/February:14-15. Pool, W. 1962. Feeding habits of the harlequin. Wildfowl Trust Ann. Rep. 13:126-129.

Pool, W. 1962. Feeding habits of the harlequin. Wildfowl Trust Ann. Rep. 13:126-129. Reichel, J. D., D. L. Genter, and D. P. Hendricks. 1997. Harlequin Duck research and monitoring in Montana: 1996. Unpublished report, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 77 pp.

Reichel, J. D., D. L. Genter, and D. P. Hendricks. 1997. Harlequin Duck research and monitoring in Montana: 1996. Unpublished report, Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 77 pp. Reichel, J., D. Genter, and D.P. Hendricks. 1995. Ecology of Harlequin ducks in Montana. National Park Service Research Report, Glacier N.P. 2 p.

Reichel, J., D. Genter, and D.P. Hendricks. 1995. Ecology of Harlequin ducks in Montana. National Park Service Research Report, Glacier N.P. 2 p. Reichel, J.D. and S.G. Beckstrom. 1994. Northern bog lemming survey: 1993. Unpublished report. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 87 pp.

Reichel, J.D. and S.G. Beckstrom. 1994. Northern bog lemming survey: 1993. Unpublished report. Montana Natural Heritage Program. Helena, MT. 87 pp. Richards, W., and A. Edmonds. 2004. Harlequin Duck surveys, Upper McDonald Creek, Glacier National Park. Chapter 1 in report to Glacier National Park, Division of Science and Resources Management. 11 pp.

Richards, W., and A. Edmonds. 2004. Harlequin Duck surveys, Upper McDonald Creek, Glacier National Park. Chapter 1 in report to Glacier National Park, Division of Science and Resources Management. 11 pp. Rivera, Heniy. 1992. [5 "wildlife sighting reports" for harlequin duck sightings in 1992 by personnel of the Hungry' Horse ranger district.]

Rivera, Heniy. 1992. [5 "wildlife sighting reports" for harlequin duck sightings in 1992 by personnel of the Hungry' Horse ranger district.] Robertson, G J., F. Cooke, R. I. Goudie, and W S. Boyd. 1998b. Moult speed predicts pairing success in male Harlequin Ducks. Animal Behavior 55: 1677-1 684.

Robertson, G J., F. Cooke, R. I. Goudie, and W S. Boyd. 1998b. Moult speed predicts pairing success in male Harlequin Ducks. Animal Behavior 55: 1677-1 684. Robertson, G J., F. Cooke, R. I. Goudie, and W. S. Boyd. 1998a. The timing of pair formation in Harlequin Ducks. Condor 100:551-555.

Robertson, G J., F. Cooke, R. I. Goudie, and W. S. Boyd. 1998a. The timing of pair formation in Harlequin Ducks. Condor 100:551-555. Robertson, G. J., F. Cooke, R. I. Goudie, and W. S. Boyd. 2000. Spacing patterns, mating systems, and winter philopatry in Harlequin Ducks. Auk 117:299-307.

Robertson, G. J., F. Cooke, R. I. Goudie, and W. S. Boyd. 2000. Spacing patterns, mating systems, and winter philopatry in Harlequin Ducks. Auk 117:299-307. Rodway, M.S. 1998. Activity patterns, diet, and feeding efficiency of Harlequin Ducks breeding in northern Labrador. Canadian Journal of Zoology 76:902-909.

Rodway, M.S. 1998. Activity patterns, diet, and feeding efficiency of Harlequin Ducks breeding in northern Labrador. Canadian Journal of Zoology 76:902-909. Rodway, M.S. 1998. Habitat use by Harlequin Ducks breeding in Hebron Fjord, Labrador. Canadian Journal of Zoology 76:897-901.

Rodway, M.S. 1998. Habitat use by Harlequin Ducks breeding in Hebron Fjord, Labrador. Canadian Journal of Zoology 76:897-901. Saunders, A.A. 1914. The birds of Teton and northern Lewis & Clark counties, Montana. Condor 16:124-144.

Saunders, A.A. 1914. The birds of Teton and northern Lewis & Clark counties, Montana. Condor 16:124-144. Schirato, G. 1993. A preliminary status report of Harlequin ducks in Washington: 1993. Pp. 45-48 in: Cassirer, E. F., et al., (eds.), Status of Harlequin ducks in North America. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 83 pp.

Schirato, G. 1993. A preliminary status report of Harlequin ducks in Washington: 1993. Pp. 45-48 in: Cassirer, E. F., et al., (eds.), Status of Harlequin ducks in North America. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 83 pp. Schirato, G. and F. Sharpe. 1992. Distribution and habitat of Harlequin Ducks in northwestern Washington. in Proceedings, Harlequin Duck Symposium, April 23-24, 1992. Unpubl. Rep., 45 pp. Idaho Dept. Fish and Game, Moscow, ID.

Schirato, G. and F. Sharpe. 1992. Distribution and habitat of Harlequin Ducks in northwestern Washington. in Proceedings, Harlequin Duck Symposium, April 23-24, 1992. Unpubl. Rep., 45 pp. Idaho Dept. Fish and Game, Moscow, ID. Schyler, K. and Grisak A. 2006. Harlequin Romance. National Parks 80(2):34-38.

Schyler, K. and Grisak A. 2006. Harlequin Romance. National Parks 80(2):34-38. Sea Duck Joint Venture Management Board. 2001. Sea Duck Joint Venture Strategic Plan: 2001-2006. SDJV Continental Technical Team. Unpubl. report c/o USFWS, Anchorage, AK; CWS, Sackville, New Brunswick. 14 p. plus appendices.

Sea Duck Joint Venture Management Board. 2001. Sea Duck Joint Venture Strategic Plan: 2001-2006. SDJV Continental Technical Team. Unpubl. report c/o USFWS, Anchorage, AK; CWS, Sackville, New Brunswick. 14 p. plus appendices. Sibley, D. 2014. The Sibley guide to birds. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY. 598 pp.

Sibley, D. 2014. The Sibley guide to birds. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY. 598 pp. Skaar, P. D., D. L. Flath, and L. S. Thompson. 1985. Montana bird distribution. Montana Academy of Sciences Monograph 3(44): ii-69.

Skaar, P. D., D. L. Flath, and L. S. Thompson. 1985. Montana bird distribution. Montana Academy of Sciences Monograph 3(44): ii-69. Skaar, P.D. 1969. Birds of the Bozeman latilong: a compilation of data concerning the birds which occur between 45 and 46 N. latitude and 111 and 112 W. longitude, with current lists for Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, impinging Montana counties and Yellowstone National Park. Bozeman, MT. 132 p.

Skaar, P.D. 1969. Birds of the Bozeman latilong: a compilation of data concerning the birds which occur between 45 and 46 N. latitude and 111 and 112 W. longitude, with current lists for Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, impinging Montana counties and Yellowstone National Park. Bozeman, MT. 132 p. Skalski, J.R. 1995. Use of 'bellwether' stations and rotational sampling designs to monitor Harlequin Duck abundance. Unpubl. rept. U. of Wash., Seattle. 19pp.

Skalski, J.R. 1995. Use of 'bellwether' stations and rotational sampling designs to monitor Harlequin Duck abundance. Unpubl. rept. U. of Wash., Seattle. 19pp. Smith, C, F. Cooke, and R. I. Goudie. 1998. Ageing Harlequin Duck Histrionicus histrionicus drakes using plumage characteristics. Wildfowl 49:245-248.

Smith, C, F. Cooke, and R. I. Goudie. 1998. Ageing Harlequin Duck Histrionicus histrionicus drakes using plumage characteristics. Wildfowl 49:245-248. Smith, C. 1996. Banff National Park Harlequin duck research project- progress report: 1995 field season. Banff N.P., Alberta, Canada: Heritage Resource Conservation, Parks Canada. 64 p.

Smith, C. 1996. Banff National Park Harlequin duck research project- progress report: 1995 field season. Banff N.P., Alberta, Canada: Heritage Resource Conservation, Parks Canada. 64 p. Smith, C. 1996. Banff National Park Harlequin duck research project: progress report: 1996 field season. Heritage Resource Conservation, Parks Canada, Banff, Alberta, Canada. 43 pp.

Smith, C. 1996. Banff National Park Harlequin duck research project: progress report: 1996 field season. Heritage Resource Conservation, Parks Canada, Banff, Alberta, Canada. 43 pp. Smith, C. 1999. Banff National Park Harlequin Duck research project - 1998 progress report. Unpublished technical report, Heritage Resource Conservation, BanffNational Park, Alberta, Canada. 40 pp.

Smith, C. 1999. Banff National Park Harlequin Duck research project - 1998 progress report. Unpublished technical report, Heritage Resource Conservation, BanffNational Park, Alberta, Canada. 40 pp. Smith, C. M., F. Cooke, G. J. Robertson, R. I. Goudie, and W. S. Boyd. 2000. Long-term pair bonds in Harlequin Ducks. Condor 102:201-205.

Smith, C. M., F. Cooke, G. J. Robertson, R. I. Goudie, and W. S. Boyd. 2000. Long-term pair bonds in Harlequin Ducks. Condor 102:201-205. Smith, Cyndi. 2000. Harlequin Duck monitoring plan for Banff National Park. Unpublished Technical Report. Parks Canada. Banff, Alberta, Canada.19pp + appendices and maps.

Smith, Cyndi. 2000. Harlequin Duck monitoring plan for Banff National Park. Unpublished Technical Report. Parks Canada. Banff, Alberta, Canada.19pp + appendices and maps. Smith, Cyndi. 2000. MS Thesis. SImon Fraser University. Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. 83pp.

Smith, Cyndi. 2000. MS Thesis. SImon Fraser University. Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. 83pp. Smith, Cyndi. 2000. Population dynamics and breeding ecology of Harlequin Ducks in Banff National Park, ALberta, 1995-1999. Unpublished Technical Report. Parks Canada, Banff National Park. Banff, Alberta, Canada. 59pp + appendices.

Smith, Cyndi. 2000. Population dynamics and breeding ecology of Harlequin Ducks in Banff National Park, ALberta, 1995-1999. Unpublished Technical Report. Parks Canada, Banff National Park. Banff, Alberta, Canada. 59pp + appendices. Swan River National Wildlife Refuge. 1982. Birds of the Swan River NWR. Kalispell, MT: NW MT Fish and Wildlife Center pamphlet.

Swan River National Wildlife Refuge. 1982. Birds of the Swan River NWR. Kalispell, MT: NW MT Fish and Wildlife Center pamphlet. Thompson, J., R. Goggans, P. Greenlee, and S. Dowlan. 1993. Abundance, distribution and habitat associations of the harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) in the Cascade Mountains, Oregon. Unpublished report prepared for cooperative agreement between the OR DepT. of Fish and Wildlife, Willamette National Forest, Mt. Hood National Forest, and the Bureau of Land Management, Salem District. 37 p.

Thompson, J., R. Goggans, P. Greenlee, and S. Dowlan. 1993. Abundance, distribution and habitat associations of the harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) in the Cascade Mountains, Oregon. Unpublished report prepared for cooperative agreement between the OR DepT. of Fish and Wildlife, Willamette National Forest, Mt. Hood National Forest, and the Bureau of Land Management, Salem District. 37 p. Thompson, L.S. 1985. A harlequin romance. Montana Outdoors 16(2):21-25.

Thompson, L.S. 1985. A harlequin romance. Montana Outdoors 16(2):21-25. Titone, J. 1989. Biologists track reclusive harlequin duck. Spokane, WA: The Spokane Chronicle. 9 July 1989. pp. A1,A11.

Titone, J. 1989. Biologists track reclusive harlequin duck. Spokane, WA: The Spokane Chronicle. 9 July 1989. pp. A1,A11. Turbak, G. 1997. Enigma on the wing, the bizarre life of the harlequin duck. National Wildlife Dec/Jan 1997:34-39.

Turbak, G. 1997. Enigma on the wing, the bizarre life of the harlequin duck. National Wildlife Dec/Jan 1997:34-39. U.S. Forest Service. 1991. Forest and rangeland birds of the United States: Natural history and habitat use. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Agricultural Handbook 688. 625 pages.

U.S. Forest Service. 1991. Forest and rangeland birds of the United States: Natural history and habitat use. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Agricultural Handbook 688. 625 pages. Wade, J.M. 1881. Rare finds. Ornithologist and Oölogist 6(6):44.

Wade, J.M. 1881. Rare finds. Ornithologist and Oölogist 6(6):44. Waldt, R. 1995. The Pine Butte Swamp Preserve bird list. Choteau, MT: The Nature Conservancy. Updated August 1995.

Waldt, R. 1995. The Pine Butte Swamp Preserve bird list. Choteau, MT: The Nature Conservancy. Updated August 1995. Wallea R. L. and C. R. Groves. 1989. Distribution breeding biology and nesting habitat of harlequin ducks {Histrionicus histrionicus) in northern Idaho. Report on Challenge Cost Share Project. 40 pp.

Wallea R. L. and C. R. Groves. 1989. Distribution breeding biology and nesting habitat of harlequin ducks {Histrionicus histrionicus) in northern Idaho. Report on Challenge Cost Share Project. 40 pp. Wallen, R. 1992. Annual variation in Harlequin Duck population size, productivity and fidelity in Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. in Proceedings, Harlequin Duck Symposium, April 23-24, 1992. Unpubl. Rep., 45pp. Idaho Dept. Fish and Game, Moscow, ID.

Wallen, R. 1992. Annual variation in Harlequin Duck population size, productivity and fidelity in Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. in Proceedings, Harlequin Duck Symposium, April 23-24, 1992. Unpubl. Rep., 45pp. Idaho Dept. Fish and Game, Moscow, ID. Wallen, R. 1992. Harlequin duck status report 1992: Wyoming. Pp. 49-54 in: Cassirer, E. F., et al., (eds.), Status of Harlequin ducks in North America. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 83 pp.

Wallen, R. 1992. Harlequin duck status report 1992: Wyoming. Pp. 49-54 in: Cassirer, E. F., et al., (eds.), Status of Harlequin ducks in North America. Harlequin Duck Working Group. 83 pp. Wallen, R. L. 1987. Annual brood survey for harlequin ducks in Grand Teton National Park. Grand Teton Nat. Pk., Resource Management. 15 pp.

Wallen, R. L. 1987. Annual brood survey for harlequin ducks in Grand Teton National Park. Grand Teton Nat. Pk., Resource Management. 15 pp. Wallen, R. L. 1991. Annual variation in harlequin duck population size, productivity and fidelity to Grand Teton National Park. Off. of Science and Res. Mgmt. Grand Teton National Park, WY. 7 pp.

Wallen, R. L. 1991. Annual variation in harlequin duck population size, productivity and fidelity to Grand Teton National Park. Off. of Science and Res. Mgmt. Grand Teton National Park, WY. 7 pp. Wallen, R.L. 1987. Habitat utilization by harlequin ducks in Grand Teton National Park. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 67 p.

Wallen, R.L. 1987. Habitat utilization by harlequin ducks in Grand Teton National Park. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 67 p. Wallen, R.L. 1987. Habitat utilization of harlequin ducks in Grand teton National Park. M.S. Thesis, Montana St. Univ., Bozeman. 67pp.

Wallen, R.L. 1987. Habitat utilization of harlequin ducks in Grand teton National Park. M.S. Thesis, Montana St. Univ., Bozeman. 67pp. Wallen, R.L. and C.R. Groves. 1988. Status and distribution of Harlequin Ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) in northern Idaho. Boise, ID: Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 34 p.

Wallen, R.L. and C.R. Groves. 1988. Status and distribution of Harlequin Ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) in northern Idaho. Boise, ID: Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 34 p. Wallen, R.L. and C.R. Groves. 1989. Distribution, breeding biology and nesting habitat of Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) in northern Idaho. Report on Cooperative Challenge Cost Share Project. 39 p.

Wallen, R.L. and C.R. Groves. 1989. Distribution, breeding biology and nesting habitat of Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) in northern Idaho. Report on Cooperative Challenge Cost Share Project. 39 p. Warren, E.R. 1914. Harlequin duck in Glacier National Park, Montana. Auk 31:535.

Warren, E.R. 1914. Harlequin duck in Glacier National Park, Montana. Auk 31:535. Wild Bird Society of Japan. 1989. Sea ducks: harlequin duck. P. 56 in: Sonobe, K. and J. W. Robinson, (eds.), A field guide to the birds of Japan. Kodansha International Ltd., Tokyo, New York, San Francisco.

Wild Bird Society of Japan. 1989. Sea ducks: harlequin duck. P. 56 in: Sonobe, K. and J. W. Robinson, (eds.), A field guide to the birds of Japan. Kodansha International Ltd., Tokyo, New York, San Francisco. Wright, K. G, G. J. Robertson, and R. I. Goudie. 1998. Evidence of spring staging and migration route of individual breeding Harlequin Ducks, Histrionicus histrionicus, in southern British Columbia. Canadian Field- Naturalist 1 12:518-519.

Wright, K. G, G. J. Robertson, and R. I. Goudie. 1998. Evidence of spring staging and migration route of individual breeding Harlequin Ducks, Histrionicus histrionicus, in southern British Columbia. Canadian Field- Naturalist 1 12:518-519.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "Harlequin Duck"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Birds"