View in other NatureServe Network Field Guides

NatureServe

Montana

Utah

Wyoming

Idaho

Wisconsin

British Columbia

South Carolina

Yukon

California

New York

White-tailed Prairie Dog - Cynomys leucurus

State Rank Reason (see State Rank above)

Within Montana, this species if found only in a small geographic area and the total population exists within a few colonies. The population appears to have declined over the last few decades, and faces ongoing threats from sylvatic plague.

- Details on Status Ranking and Review

White-tailed Prairie Dog (Cynomys leucurus) Conservation Status Review

Review Date = 09/26/2018

Area of Occupancy

ScoreB - 0.4-4 km squared (about 100-1,000 acres)

CommentIn 2009, 119 to 336 acres occupied. More recent survey data not comprehensive enough to determine Area of Occupancy

Long-term Trend

ScoreU - Unknown. Long-term trend in population, range, area occupied, or number or condition of occurrences unknown

CommentUnknown

Short-term Trend

ScoreA - Severely Declining. Decline of >70% in population, range, area occupied, and/or number or condition of occurrences

CommentIn 2016, 5 colonies were occupied and only 4 of 23 historic colonies were active. This may indicate a substantial decline in recent years.

Threats

ScoreA - Substantial, imminent threat. Threat is moderate to severe and imminent for most (>60%) of the population or area.

CommentPlague has had substantial negative impacts on this species, and mortality events are still common. Persecution of populations due to perceived competition with livestock and the disruption to agriculture caused by burrows and clipping remains an ongoing threat.

SeverityModerate - Major reduction of species population or long-term degradation or reduction of habitat in Montana, requiring 50-100 years for recovery.

CommentIn the absence of threats recovery could occur in 50 to 100 years

ScopeHigh - > 60% of total population or area affected

CommentDue to small population size threats would impact close to 100% of occurrences

ImmediacyHigh - Threat is operational (happening now) or imminent (within a year).

CommentOngoing

Intrinsic Vulnerability

ScoreB - Moderately Vulnerable. Species exhibits moderate age of maturity, frequency of reproduction, and/or fecundity such that populations generally tend to recover from decreases in abundance over a period of several years (on the order of 5-20 years or 2-5 generations); or species has moderate dispersal capability such that extirpated populations generally become reestablished through natural recolonization (unaided by humans).

CommentModerate fecundity and dispersal capabilities

Environmental Specificity

ScoreB - Narrow. Specialist. Specific habitat(s) or other abiotic and/or biotic factors (see above) are used or required by the Element, but these key requirements are common and within the generalized range of the species within the area of interest.

CommentFound in relatively limited and unique habitat within the state

Raw Conservation Status Score

Score

3.5 + -0.75 (geographic distribution) + 0 (environmental specificity) + -1 (short-term trend) + -1 (threats) = 0.75

General Description

White-tailed prairie dogs are medium-sized squirrel-like rodents. Adults weigh around 500-1000 grams; males are about 36 centimeters long and females 31 centimeters long (Foresman 2012). Legs are short and feet have well developed claws for digging. The tail is short and flattened with a whitish tip. The back is a yellowish-buff mixed with black that becomes lighter on the belly. Distinctive brownish-black patches are present above the eyes and on the cheeks.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Distinguished from the only other prairie dog found in Montana, the black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus), by its smaller size and white-tipped tail (Foresman 2012).

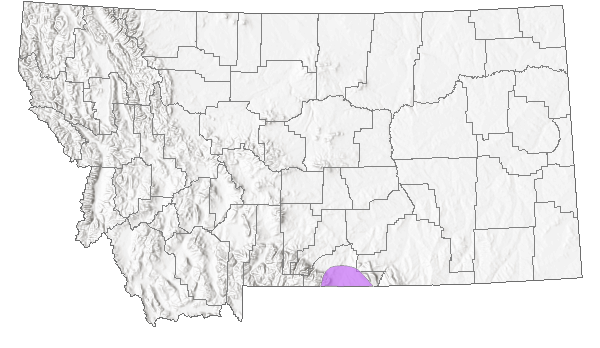

Species Range

Montana Range

Range Descriptions

Native

Native

Western Hemisphere Range

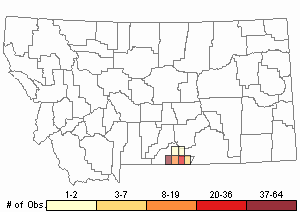

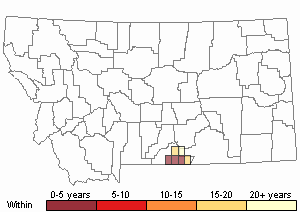

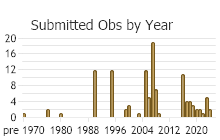

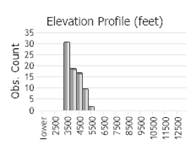

Observations in Montana Natural Heritage Program Database

Number of Observations: 132

(Click on the following maps and charts to see full sized version)

Map Help and Descriptions

Relative Density

Recency

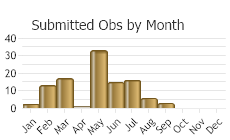

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

(Observations spanning multiple months or years are excluded from time charts)

Migration

White-tailed prairie dogs are non-migratory. Juveniles disperse to other colonies or the periphery of their natal colony in September/October.

Habitat

Throughout their range, white-tailed prairie dogs inhabit xeric sites with mixed stands of shrubs and grasses. In Montana they inhabit these habitats dominated by two types of vegetation: areas with Gardener's saltbush (Atriplex gardneri) with lesser amounts of big sage, and areas with small-flowered marsh-elder (Iva axillaris) and winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata)(Flath and Paulick 1979). They live at higher elevations and in meadows with more diverse grass and herb cover than do black-tailed prairie dogs (Wilson and Ruff 1999) although their range in Montana is at relatively lower elevations than other areas across their distribution (Foresman 2012).

Ecological Systems Associated with this Species

- Details on Creation and Suggested Uses and Limitations

How Associations Were Made

We associated the use and habitat quality (common or occasional) of each of the 82 ecological systems mapped in Montana for

vertebrate animal species that regularly breed, overwinter, or migrate through the state by:

- Using personal observations and reviewing literature that summarize the breeding, overwintering, or migratory habitat requirements of each species (Dobkin 1992, Hart et al. 1998, Hutto and Young 1999, Maxell 2000, Foresman 2012, Adams 2003, and Werner et al. 2004);

- Evaluating structural characteristics and distribution of each ecological system relative to the species' range and habitat requirements;

- Examining the observation records for each species in the state-wide point observation database associated with each ecological system;

- Calculating the percentage of observations associated with each ecological system relative to the percent of Montana covered by each ecological system to get a measure of "observations versus availability of habitat".

Species that breed in Montana were only evaluated for breeding habitat use, species that only overwinter in Montana were only evaluated for overwintering habitat use, and species that only migrate through Montana were only evaluated for migratory habitat use.

In general, species were listed as associated with an ecological system if structural characteristics of used habitat documented in the literature were present in the ecological system or large numbers of point observations were associated with the ecological system.

However, species were not listed as associated with an ecological system if there was no support in the literature for use of structural characteristics in an ecological system,

even if point observations were associated with that system.

Common versus occasional association with an ecological system was assigned based on the degree to which the structural characteristics of an ecological system matched the preferred structural habitat characteristics for each species as represented in scientific literature.

The percentage of observations associated with each ecological system relative to the percent of Montana covered by each ecological system was also used to guide assignment of common versus occasional association.

If you have any questions or comments on species associations with ecological systems, please contact the Montana Natural Heritage Program's Senior Zoologist.

Suggested Uses and Limitations

Species associations with ecological systems should be used to generate potential lists of species that may occupy broader landscapes for the purposes of landscape-level planning.

These potential lists of species should not be used in place of documented occurrences of species (this information can be requested at:

mtnhp.org/requests) or systematic surveys for species and evaluations of habitat at a local site level by trained biologists.

Users of this information should be aware that the land cover data used to generate species associations is based on imagery from the late 1990s and early 2000s and was only intended to be used at broader landscape scales.

Land cover mapping accuracy is particularly problematic when the systems occur as small patches or where the land cover types have been altered over the past decade.

Thus, particular caution should be used when using the associations in assessments of smaller areas (e.g., evaluations of public land survey sections).

Finally, although a species may be associated with a particular ecological system within its known geographic range, portions of that ecological system may occur outside of the species' known geographic range.

Literature Cited

- Adams, R.A. 2003. Bats of the Rocky Mountain West; natural history, ecology, and conservation. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado. 289 p.

- Dobkin, D. S. 1992. Neotropical migrant land birds in the Northern Rockies and Great Plains. USDA Forest Service, Northern Region. Publication No. R1-93-34. Missoula, MT.

- Foresman, K.R. 2012. Mammals of Montana. Second edition. Mountain Press Publishing, Missoula, Montana. 429 pp.

- Hart, M.M., W.A. Williams, P.C. Thornton, K.P. McLaughlin, C.M. Tobalske, B.A. Maxell, D.P. Hendricks, C.R. Peterson, and R.L. Redmond. 1998. Montana atlas of terrestrial vertebrates. Montana Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, University of Montana, Missoula, MT. 1302 p.

- Hutto, R.L. and J.S. Young. 1999. Habitat relationships of landbirds in the Northern Region, USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station RMRS-GTR-32. 72 p.

- Maxell, B.A. 2000. Management of Montana's amphibians: a review of factors that may present a risk to population viability and accounts on the identification, distribution, taxonomy, habitat use, natural history, and the status and conservation of individual species. Report to U.S. Forest Service Region 1. Missoula, MT: Wildlife Biology Program, University of Montana. 161 p.

- Werner, J.K., B.A. Maxell, P. Hendricks, and D. Flath. 2004. Amphibians and reptiles of Montana. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company. 262 p.

Food Habits

White-tailed prairie dogs feed primarily on forbs. Early spring diets in Colorado showed white-tailed prairie dogs fed heavily on sagebrush and saltbush, with a shift towards dandelions and goosefoot as these forbs became available (Foresman 2012). Food habits in Montana are probably similar.

Ecology

Colonies in Montana average 54 acres. They do not clip vegetation like black-tailed prairie dogs. Maternity burrows are extensively excavated and can be identified by the presence of current accessory digging (Flath 1978, 1979).

Reproductive Characteristics

No specific reproductive information is available for Montana, however in other parts of their range breeding occurs shortly after female emergence from hibernation in late March and early April (Clark et al. 1971). Gestation requires about 30 days and young are born in late April and early May. Litter sizes range from 2 to 8 and average around 5 young (Flath 1979). One litter is produced annually. Juveniles appear above ground in early June, 5 to 7 weeks after birth. Both sexes breed as 1-year-olds.

Management

White-tailed Prairie Dogs are classified as a Species of Concern in Montana due to a limited distribution within the state and a variety of threats to the population. Prairie dogs are managed under the

Conservation Plan for Black-tailed and White-tailed Prairie Dogs in Montana (Montana Prairie Dog Working Group 2002). Please consult this plan for details concerning prairie dog management in Montana.

On December 4, 2017, after a thorough review of the best-available scientific and commercial information, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service released a 12-month finding that the species is not warranted for listing under the Endangered Species Act at this time because it is not currently in danger of extinction and is not likely to become in danger of extinction within the foreseeable future (USFWS 2017).

References

- Literature Cited AboveLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication Clark, T. W., R. S. Hoffmann, and C. F. Nadler. 1971. Cynomys leucurus. Mammalian Species 7:1-4.

Clark, T. W., R. S. Hoffmann, and C. F. Nadler. 1971. Cynomys leucurus. Mammalian Species 7:1-4. Flath, D.L. 1978. At home with the prairie dog. Montana Outdoors 9(2):3-8.

Flath, D.L. 1978. At home with the prairie dog. Montana Outdoors 9(2):3-8. Flath, D.L. 1979. Status of the white-tailed prairie dog in Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 38:63-67.

Flath, D.L. 1979. Status of the white-tailed prairie dog in Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Sciences 38:63-67. Foresman, K.R. 2012. Mammals of Montana. Second edition. Mountain Press Publishing, Missoula, Montana. 429 pp.

Foresman, K.R. 2012. Mammals of Montana. Second edition. Mountain Press Publishing, Missoula, Montana. 429 pp. Montana Prairie Dog Working Group. 2002. Conservation plan for black-tailed and white-tailed prairie dogs in Montana. Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. Helena MT. 51 pp.

Montana Prairie Dog Working Group. 2002. Conservation plan for black-tailed and white-tailed prairie dogs in Montana. Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. Helena MT. 51 pp. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2017. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; 12-month findings on petitions to list four species as Endangered or Threatened Species. Federal Register 82(233): 57562-57565.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2017. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; 12-month findings on petitions to list four species as Endangered or Threatened Species. Federal Register 82(233): 57562-57565. Wilson, D. E. and S. Ruff. 1999. The Smithsonian book of North American mammals. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. 750 pp.

Wilson, D. E. and S. Ruff. 1999. The Smithsonian book of North American mammals. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. 750 pp.

- Additional ReferencesLegend:

View Online Publication

View Online Publication

Do you know of a citation we're missing? Atkinson, E.C. and M.L. Atkinson. 2005. Priority sending and receiving sites for White-tailed Prairie Dog relocation in Carbon County, Montana. Unpublished report to the Bureau of Land Management. Marmot's Edge Conservation. Belfry, Montana. 11pp.

Atkinson, E.C. and M.L. Atkinson. 2005. Priority sending and receiving sites for White-tailed Prairie Dog relocation in Carbon County, Montana. Unpublished report to the Bureau of Land Management. Marmot's Edge Conservation. Belfry, Montana. 11pp. Bureau of Land Management. 1979?. Habitat management plan prairie dog ecosystems. USDI, BLM, Montana State Office. Wildlife Habitat Area MT-02-06-07-S1. 61 pp.

Bureau of Land Management. 1979?. Habitat management plan prairie dog ecosystems. USDI, BLM, Montana State Office. Wildlife Habitat Area MT-02-06-07-S1. 61 pp. Burns, J.A., D.L. Flath and T.W. Clark. 1989. On the structure and function of white-tailed prairie dog burrows. Great Basin Naturalist 49(4):517-524.

Burns, J.A., D.L. Flath and T.W. Clark. 1989. On the structure and function of white-tailed prairie dog burrows. Great Basin Naturalist 49(4):517-524. Campbell, T.M. III and T.W. Clark. 1981. Colony characteristics and vertebrate associates of white-tailed and black-tailed prairie dogs in Wyoming. The American Midland Naturalist 105(2):269-276.

Campbell, T.M. III and T.W. Clark. 1981. Colony characteristics and vertebrate associates of white-tailed and black-tailed prairie dogs in Wyoming. The American Midland Naturalist 105(2):269-276. Faunawest Wildlife Consultants. 1998. Status of the black-tailed and white-tailed prairie dog in Montana. Prepared for Montana Department of Fish, WIldlife & Parks.

Faunawest Wildlife Consultants. 1998. Status of the black-tailed and white-tailed prairie dog in Montana. Prepared for Montana Department of Fish, WIldlife & Parks. Faunawest Wildlife Consultants. 1999. Status of the black and white-tailed prairie dogs in Montana. Helena, MT: Report to Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. 37 p.

Faunawest Wildlife Consultants. 1999. Status of the black and white-tailed prairie dogs in Montana. Helena, MT: Report to Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. 37 p. Flath, D.A. and R.K. Paulick. 1979. Mound characteristics of white-tailed prairie dog maternity burrows. American Midland Naturalist 102(2):395-398.

Flath, D.A. and R.K. Paulick. 1979. Mound characteristics of white-tailed prairie dog maternity burrows. American Midland Naturalist 102(2):395-398. Flath, D.L. 1979. Nongame species of special interest or concern: Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes. Wildlife Division, Montana Department of Fish and Game. Helena, MT.

Flath, D.L. 1979. Nongame species of special interest or concern: Mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes. Wildlife Division, Montana Department of Fish and Game. Helena, MT. Foresman, K.R. 2001. The wild mammals of Montana. American Society of Mammalogists, Special Publication Number 12. Lawrence, KS. 278 pp.

Foresman, K.R. 2001. The wild mammals of Montana. American Society of Mammalogists, Special Publication Number 12. Lawrence, KS. 278 pp. FWP and BLM. 2010. White-tailed Prairie Dog (Cynomys leucurus) Translocation Efforts in Montana 2006-2010. MTFWP Region 5 Wildlife Division with BLM Billings Field Office. 19pp

FWP and BLM. 2010. White-tailed Prairie Dog (Cynomys leucurus) Translocation Efforts in Montana 2006-2010. MTFWP Region 5 Wildlife Division with BLM Billings Field Office. 19pp Goodwin, H.T. 1995. Pliocene-Pleistocene biogeographic history of prairie dogs, genus Cynomys (Sciuridae). Journal of Mammalogy 76:100-122.

Goodwin, H.T. 1995. Pliocene-Pleistocene biogeographic history of prairie dogs, genus Cynomys (Sciuridae). Journal of Mammalogy 76:100-122. Hoffmann, R.S. and D.L. Pattie. 1968. A guide to Montana mammals: identification, habitat, distribution, and abundance. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 133 p.

Hoffmann, R.S. and D.L. Pattie. 1968. A guide to Montana mammals: identification, habitat, distribution, and abundance. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 133 p. Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society.

Joslin, Gayle, and Heidi B. Youmans. 1999. Effects of recreation on Rocky Mountain wildlife: a review for Montana. [Montana]: Montana Chapter of the Wildlife Society. King. J. A. 1955. Social behaivor, social organization, and population dynamics in a black-tailed prairie dog town in the Black Hills of South Dakota. University of Michigan, Contributions from the Laboratory of Vertebrate Biology 67:1-123.

King. J. A. 1955. Social behaivor, social organization, and population dynamics in a black-tailed prairie dog town in the Black Hills of South Dakota. University of Michigan, Contributions from the Laboratory of Vertebrate Biology 67:1-123. Linder, Rayond L., and Conrad N. Hillman, 1973, Proceedings of the Black-footed Ferret and Prairie Dog Workshop, September 4-6, 1973. Rapid City, South Dakota.

Linder, Rayond L., and Conrad N. Hillman, 1973, Proceedings of the Black-footed Ferret and Prairie Dog Workshop, September 4-6, 1973. Rapid City, South Dakota. Oldemeyer, J.L., D.E. Biggins, B.J. Miller, and R. Crete, editors. 1993. Proc. of the symposium on the management of prairie dog complexes for the reintroduction of the black-footed ferret. U.S. Fish Wildl. Serv. Biol. Rep., No. 13. 96 pp.

Oldemeyer, J.L., D.E. Biggins, B.J. Miller, and R. Crete, editors. 1993. Proc. of the symposium on the management of prairie dog complexes for the reintroduction of the black-footed ferret. U.S. Fish Wildl. Serv. Biol. Rep., No. 13. 96 pp. Reid, F. 2006. Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America, 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston and New York, 608 pp.

Reid, F. 2006. Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America, 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston and New York, 608 pp. Schomburg, J.W. 2003. Development and evaluation of predictive models for managing Golden Eagle electrocutions. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State Universtiy. 98 p.

Schomburg, J.W. 2003. Development and evaluation of predictive models for managing Golden Eagle electrocutions. M.Sc. Thesis. Bozeman, MT: Montana State Universtiy. 98 p. Smith, R. E. 1958. Natural history of the prairie dog in Kansas. Kansas University. Museum of Natural History: Miscellaneous Publications Number 16. 36 pp.

Smith, R. E. 1958. Natural history of the prairie dog in Kansas. Kansas University. Museum of Natural History: Miscellaneous Publications Number 16. 36 pp. Thompson, L.S. 1982. Distribution of Montana amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. Bozeman: Montana Audubon Council. 24 pp.

Thompson, L.S. 1982. Distribution of Montana amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. Bozeman: Montana Audubon Council. 24 pp. Tileston, J.V., and R.R. Lechleitner. 1966. Some comparisons of the black-tailed and white-tailed prairie dogs in north-central Colorado. Am. Midl. Nat. 75: 292-316.

Tileston, J.V., and R.R. Lechleitner. 1966. Some comparisons of the black-tailed and white-tailed prairie dogs in north-central Colorado. Am. Midl. Nat. 75: 292-316. USFWS. 1989. Wildlife Reveiw - Database. Fort Collins, CO: Office of Information Transfer. 65 p.

USFWS. 1989. Wildlife Reveiw - Database. Fort Collins, CO: Office of Information Transfer. 65 p. Witmer, G.W. and K.A. Fagerstone. No date. The use of toxicants in prairie dog management: an overview. Fort Collins, CO: USDA/APHIS/WS National Wildlife Research Center. 9 p.

Witmer, G.W. and K.A. Fagerstone. No date. The use of toxicants in prairie dog management: an overview. Fort Collins, CO: USDA/APHIS/WS National Wildlife Research Center. 9 p.

- Web Search Engines for Articles on "White-tailed Prairie Dog"

- Additional Sources of Information Related to "Mammals"